Italian battleship Littorio

Littorio was the lead ship of her class of battleship; she served in the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) during World War II. She was named after the Lictor ("Littorio" in Italian), in ancient times the bearer of the Roman fasces, which was adopted as the symbol of Italian Fascism. Littorio and her sister Vittorio Veneto were built in response to the French battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg. They were Italy's first modern battleships, and the first 35,000-ton capital ships of any nation to be laid down under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. Littorio was laid down in October 1934, launched in August 1937, and completed in May 1940.

Littorio | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Littorio |

| Namesake | The Lictor, a symbol of Italian Fascism[1] |

| Operator | Regia Marina |

| Ordered | 10 June 1934 |

| Builder | Ansaldo, Genoa Sestri Ponente |

| Laid down | 28 October 1934 |

| Launched | 22 August 1937 |

| Sponsored by | Signora Teresa Ballerino Cabella |

| Commissioned | 6 May 1940 |

| Decommissioned | 1 June 1948 |

| Renamed | Italia |

| Stricken | 1 June 1948 |

| Fate | Scrapped at La Spezia 1952–54 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Littorio-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 237.76 m (780 ft 1 in) |

| Beam | 32.82 m (107 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 9.6 m (31 ft 6 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 30 kn (35 mph; 56 km/h) |

| Range | 3,920 mi (6,310 km; 3,410 nmi) at 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Complement | 1,830 to 1,950 |

| Sensors and processing systems | EC 3 ter 'Gufo' radar |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 3 aircraft (IMAM Ro.43 or Reggiane Re.2000) |

| Aviation facilities | 1 stern catapult |

Shortly after her commissioning, Littorio was badly damaged during the British air raid on Taranto on 11 November 1940, which put her out of action until the following March. Littorio thereafter took part in several sorties to catch the British Mediterranean Fleet, most of which failed to result in any action, the notable exception being the Second Battle of Sirte in March 1942, where she damaged several British warships. Littorio was renamed Italia in July 1943 after the fall of the Fascist government. On 9 September 1943, the Italian fleet was attacked by German bombers while it was on its way to internment. During this action, which saw the destruction of her sister Roma, Italia herself was hit by a Fritz X radio-controlled bomb, causing significant damage to her bow. As part of the armistice agreement, Italia was interned at Malta, Alexandria, and finally in the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal, where she remained until 1947. Italia was awarded to the United States as a war prize and scrapped at La Spezia in 1952–54.

Description

Littorio and her sister Vittorio Veneto were designed in response to the French Dunkerque-class battleships.[2] Littorio was 237.76 meters (780 ft 1 in) long overall, had a beam of 32.82 m (107 ft 8 in) and a draft of 9.6 m (31 ft 6 in). She was designed with a standard displacement of 40,724 long tons (41,377 t), a violation of the 35,000-long-ton (36,000 t) restriction of the Washington Naval Treaty; at full combat loading, she displaced 45,236 long tons (45,962 t). The ship was powered by four Belluzo geared steam turbines rated at 128,000 shaft horsepower (95,000 kW). Steam was provided by eight oil-fired Yarrow boilers. The engines provided a top speed of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) and a range of 3,920 mi (6,310 km; 3,410 nmi) at 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph). Littorio had a crew of 1,830 to 1,950 over the course of her career.[3][4]

Littorio's main armament consisted of nine 381 mm (15 in) 50-caliber Model 1934 guns in three triple turrets; two turrets were placed forward in a superfiring arrangement and the third was located aft. Her secondary anti-surface armament consisted of twelve 152 mm (6 in) /55 Model 1934/35 guns in four triple turrets placed at the corners of the superstructure. These were supplemented by four 120 mm (4.7 in) /40 Model 1891/92 guns in single mounts; these guns were old weapons and were primarily intended to fire star shells. Littorio was equipped with an anti-aircraft battery that comprised twelve 90 mm (3.5 in) /50 Model 1938 guns in single mounts, twenty 37 mm (1.5 in)/54 /54 guns in eight twin and four single mounts, and sixteen 20 mm (0.79 in) /65 guns in eight twin mounts.[5] A further twelve 20 mm guns in twin mounts were installed in 1942. She received an EC 3 bis radar set in August 1941, an updated version in April 1942—which proved to be unsuccessful in service—and finally the EC 3 ter model in September 1942.[6]

The ship was protected by a main armor belt that was 280 mm (11 in) thick with a second layer of steel that was 70 mm (2.8 in) thick. The main deck was 162 mm (6.4 in) thick in the central area of the ship and reduced to 45 mm (1.8 in) in less critical areas. The main battery turrets were 350 mm (14 in) thick and the lower turret structure was housed in barbettes that were also 350 mm thick. The secondary turrets had 280 mm thick faces and the conning tower had 260 mm (10 in) thick sides.[4] Littorio was fitted with a catapult on her stern and equipped with three IMAM Ro.43 reconnaissance float planes or Reggiane Re.2000 fighters.[7]

Service history

Littorio was laid down at the Ansaldo shipyards in Genoa on 28 October 1934 to commemorate the Fascist Party's March on Rome in 1922. Her sister Vittorio Veneto was laid down the same day.[8] Changes to the design and a lack of armor plating led to delays in the building schedule, causing a three-month slip in the launch date from the original plan of May 1937. Littorio was launched on 22 August 1937, during a ceremony attended by many Italian dignitaries. She was sponsored by Signora Teresa Ballerino Cabella, the wife on an Ansaldo employee.[9] After her launch, the fitting out period lasted until early 1940. During this time, Littorio's bow was modified to lessen vibration and reduce wetness over the bow. Littorio ran a series of sea trials over a period of two months between 23 October 1939 and 21 December 1939. She was commissioned on 6 May 1940, and after running additional trials that month, she transferred to Taranto where she—along with Vittorio Veneto—joined the 9th Division under the command of Rear Admiral Carlo Bergamini.[10]

On 31 August – 2 September 1940, Littorio sortied as part of an Italian force of five battleships, ten cruisers, and thirty-four destroyers to intercept British naval forces taking part in Operation Hats and Convoy MB.3, but contact was not made with either group due to poor reconnaissance and no action occurred.[6][11] A similar outcome resulted from the movement against British Operation "MB.5" on 29 September - 1 October; Littorio, four other battleships, eleven cruisers, and twenty-three destroyers had attempted to intercept the convoy carrying troops to Malta.[6][12]

Attack on Taranto

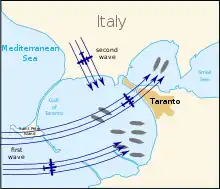

On the night of 10–11 November, the British Mediterranean Fleet launched an air raid on the harbor in Taranto. Twenty-one Swordfish torpedo bombers launched from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious attacked the Italian fleet in two waves.[13] The Italian base was defended by twenty-one 90 mm anti-aircraft guns and dozens of smaller 37 mm and 20 mm guns, along with twenty-seven barrage balloons. The defenders did not possess radar, however, and so were caught by surprise when the Swordfish arrived. Littorio and the other battleships were also not provided with sufficient anti-torpedo nets. The first wave struck at 20:35, followed by the second about an hour later.[14]

The planes scored three hits on Littorio, one hit on Duilio, and one on Conte di Cavour.[13] Of the torpedoes that struck Littorio, two hit in the bow and one struck the stern; the stern hit destroyed the rudder and shock from the explosion damaged the ship's steering gear. The two forward hits caused major flooding and led her to settle by the bows, with her decks awash up to her main battery turrets. She could not be brought into dock until 11 December due to a fourth, unexploded torpedo discovered under her keel; removing the torpedo proved to be a painstaking task, as any shift in the magnetic field around the torpedo might detonate its magnetic detonator.[15] Repairs lasted until 11 March 1941.[16]

Convoy operations

After repairs were completed, Littorio participated in an unsuccessful sortie to intercept British forces on 22–25 August. A month later, she led the attack on the Allied convoy in Operation Halberd on 27 September 1941.[16] The British force escorting the convoy included the battleships Rodney, Nelson, and Prince of Wales; Italian reconnaissance reported the presence of a powerful escort, and the Italian commander, under orders not to engage unless he possessed a strong numerical superiority, broke off the operation and returned to port.[17] On 13 December, she participated in another sweep to catch a convoy to Malta, but the attempt was broken off after Vittorio Veneto was torpedoed by a British submarine. Three days later, she steamed out to escort Operation M42, a supply convoy to Italian and German forces in North Africa.[16] By late 1941, British success at breaking the Enigma code made it increasingly difficult for Axis convoys to reach North Africa. The Italians therefore committed their battle fleet to the convoy effort to better protect the transports.[17] The next day, she took part in the First Battle of Sirte. Littorio, along with the rest of the distant covering force, engaged the escort of a British convoy heading for Malta that happened to run into the M42 convoy late in the day.[16] Littorio opened fire at extreme range, around 35,000 yards (32,000 m), but she scored no hits. Nevertheless, the heavy Italian fire forced the British force to withdraw under cover of a smokescreen and the M42 convoy reached North Africa without damage.[18][19]

On 3 January 1942, Littorio was again tasked with convoy escort, in support of Operation M43; she was back in port by 6 January. On 22 March, she participated in the Second Battle of Sirte, as the flagship for an Italian force attempting to destroy a British convoy bound for Malta.[16] After the fall of darkness, several British destroyers made a close-range attack on Littorio, but heavy fire from her main and secondary guns forced the destroyers to retreat.[20] As the destroyers withdrew, one of them hit Littorio with a single 4.7-inch (120 mm) shell, which caused minor damage to the ship's fantail.[21] During the battle, Littorio hit and seriously damaged the destroyers HMS Havock and Kingston. She also hit the cruiser Euryalus but did not inflict significant damage. Kingston limped to Malta for repairs, where she was later destroyed during an airstrike while in drydock.[22] Muzzle blast from Littorio's rear turret set one of her floatplanes on fire, though no serious damage to the ship resulted.[20] She fired a total of 181 shells from her main battery in the course of the engagement. Though the Italian fleet was unable to directly attack the convoy, it forced the transports to scatter and many were sunk the next day by air attack.[23]

Three months later, on 14 June, Littorio participated in the interception of the Operation Vigorous convoy to Malta from Alexandria. Littorio, Vittorio Veneto, four cruisers and twelve destroyers were sent to attack the convoy.[24] The British quickly located the approaching Italian fleet and launched several night air strikes in an attempt to prevent them from reaching the convoy, though the aircraft scored no hits.[25] While searching for the convoy the next day, Littorio was hit by a bomb dropped by a B-24 Liberator; the bomb hit the roof of turret no. 1 but caused negligible damage to the rangefinder hood and barbette, along with splinter damage to the deck. The turret nevertheless remained serviceable and Littorio remained with the fleet. The threat from Littorio and Vittorio Veneto forced the British convoy to abort the mission.[24][26] At 14:00, the Italians broke off the chase and returned to port; shortly before midnight that evening, Littorio was struck by a torpedo dropped by a British Wellington bomber, causing some 1,500 long tons (1,500 t) of water to flood the ship's bow. Her crew counter-flooded 350 long tons (360 t) of water to correct the list.[27] The ship was able to return to port for repairs, that lasted until 27 August.[27][24][26] She remained in Taranto until 12 December, when the fleet was moved to La Spezia.[26]

Fate

Littorio was inactive for the first six months of 1943 due to severe fuel shortages in the Italian Navy.[28] Only enough fuel was available for Littorio, Vittorio Veneto and their recently commissioned sister Roma, but even then the fuel was only enough for emergencies.[29] On 19 June 1943, an American bombing raid targeted the harbor at La Spezia and hit Littorio with three bombs.[26][30]

She was renamed Italia on 30 July after the government of Benito Mussolini fell from power. On 3 September, Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, ending her active participation in World War II. Six days later, Italia and the rest of the Italian fleet sailed for Malta, where they would be interned for the remainder of the war. While en route, the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) attacked the Italian fleet using Dornier Do 217s armed with Fritz X radio-controlled bombs. One Fritz X hit Italia just forward of turret no. 1; it passed through the ship and exited the hull, exploding in the water beneath and causing serious damage. Roma was meanwhile sunk in the attack.[26][30]

Italia and Vittorio Veneto were then moved, first to Alexandria, Egypt, and then to the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal in Egypt on 14 September; they remained there until the end of the war. On 5 February 1947, Italia was finally permitted to return to Italy. In the Treaty of Peace with Italy, signed five days later on 10 February, Italia was allocated as a war prize to the United States. She was stricken from the naval register on 1 June 1948 and broken up for scrap at La Spezia.[31]

Footnotes

- Whitley, p. 171

- Whitley, p. 170

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 435

- Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 289

- Gardiner & Chesneau, pp. 289–290

- Whitley, p. 172

- Bagnasco & de Toro, p. 48

- Bagnasco & de Toro, pp. 20–21

- Bagnasco & de Toro, pp. 117–119

- Bagnasco & de Toro, pp. 121–125

- Bagnasco & de Toro, pp. 167–169

- Bagnasco & de Toro, pp. 170–172

- Rohwer, p. 47

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 383

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 396

- Whitley, p. 175

- Stille, p. 38

- Stille, p. 39

- Garzke & Dulin, pp. 398–399

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 399

- Garzke & Dulin, pp. 399–400

- Whitley, pp. 175–176

- Stille, pp. 39–40

- Stille, p. 40

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 400

- Whitley, p. 176

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 402

- Whitley, pp. 168, 176

- Stille, p. 41

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 407

- Whitley, p. 177

References

- Bagnasco, Erminio & de Toro, Augusto (2011). The Littorio Class: Italy's Last and Largest Battleships 1937–1948. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-105-2.

- Garzke, William H. & Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Roberts, John (1980). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 280–317. ISBN 978-0-85177-146-5.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Stille, Mark (2011). Italian Battleships of World War II. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-831-2.

- Velicogna, Arrigo (2018). "The Battleship Littorio (1937)". In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87021-906-1.

- Whitley, M.J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.

External links

- Littorio specifications

- Littorio Marina Militare website