French battleship Dunkerque

Dunkerque was the lead ship of the Dunkerque class of battleships built for the French Navy in the 1930s. The class also included Strasbourg. The two ships were the first capital ships to be built by the French Navy after World War I; the planned Normandie and Lyon classes had been cancelled at the outbreak of war, and budgetary problems prevented the French from building new battleships in the decade after the war. Dunkerque was laid down in December 1932, was launched October 1935, and was completed in May 1937. She was armed with a main battery of eight 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns arranged in two quadruple gun turrets and had a top speed of 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph).

Dunkerque | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dunkerque |

| Namesake | City of Dunkirk |

| Laid down | 24 December 1932 |

| Launched | 2 October 1935 |

| Commissioned | 1 May 1937 |

| Fate | Scuttled, 27 November 1942; scrapped, 1958 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Dunkerque-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 214.5 m (704 ft) |

| Beam | 31.08 m (102.0 ft) |

| Draft | 8.7 m (29 ft) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 4 Shafts; 4 geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph) (designed) 31.06 knots (57.52 km/h; 35.74 mph) (max) |

| Range |

|

| Crew | 1,381–1,431 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 2 floatplanes |

Dunkerque and Strasbourg formed the French Navy's 1ère Division de Ligne (1st Division of the Line) prior to the Second World War. The two ships searched for German commerce raiders in the early months of the war, and Dunkerque also participated in convoy escort duties. The ship was badly damaged during the British attack at Mers-el-Kébir after the Armistice that ended the first phase of France's participation in World War II, but she was refloated and partially repaired to return to Toulon for comprehensive repairs. Dunkerque was scuttled in November 1942 to prevent her capture by the Germans, and subsequently seized and partially scrapped by the Italians and later the Germans. Her wreck remained in Toulon until she was stricken in 1955, and scrapped three years later.

Development

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty attempting to produce a satisfactory design to fill 70,000 tons as allowed by the treaty.[1] Initially, the French sought a reply to the Italian Trento-class cruisers of 1925, but all proposals were rejected. A 17,500-ton cruiser, which could have handled the Trentos, was inadequate against the old Italian battleships, however, and the 37,000-ton battlecruiser concepts were prohibitively expensive and would jeopardize further naval limitation talks. These attempts were followed by an intermediate design for a 23,690-ton protected cruiser in 1929; it was armed with 305 mm (12 in) guns, armored against 203 mm (8 in) guns, and had a speed of 29 kn (54 km/h; 33 mph). Visually, it bore a profile strikingly similar to the final Dunkerque.[2][3]

The German Deutschland-class cruisers became the new focus for French naval architects in 1929. The design had to respect the 1930 London Naval Treaty, which limited the French to two 23,333-ton ships until 1936. Drawing upon previous work, the French developed a 23,333-ton design armed with 305 mm guns, armored against the German cruisers' 280 mm (11 in) guns, and with a speed of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). As with the final Dunkerque, the main artillery was concentrated entirely forward. The design was rejected by the French parliament in July 1931 and sent back for revision. The final revision grew to 26,500 tons; the 305 mm guns were replaced by 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns, the armor was slightly improved, and the speed slightly decreased.[4][5] Parliamentary approval was granted in early 1932, and Dunkerque was ordered on 26 October.[6]

Characteristics

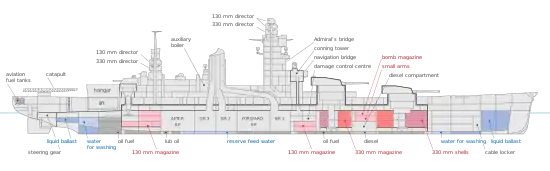

Dunkerque displaced 26,500 t (26,100 long tons) as built and 35,500 t (34,900 long tons) fully loaded, with an overall length of 214.5 m (703 ft 9 in), a beam of 31.08 m (102 ft 0 in) and a maximum draft of 8.7 m (28 ft 7 in). She was powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and six oil-fired Indret boilers, which developed a total of 112,500 shaft horsepower (83,900 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph).[7] Her crew numbered between 1,381 and 1,431 officers and men.[Note 1] The ship carried a pair of spotter aircraft on the fantail, and the aircraft facilities consisted of a steam catapult and a crane to handle the floatplanes.[7]

She was armed with eight 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns arranged in two quadruple gun turrets, both of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward of the superstructure. Her secondary armament consisted of sixteen 130 mm (5.1 in) /45 dual-purpose guns; these were mounted in three quadruple and two twin turrets. The quadruple turrets were placed on the stern, and the twin turrets were located amidships. Close range antiaircraft defense was provided by a battery of eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns in twin mounts and thirty-two 13.2 mm (0.52 in) guns in quadruple mounts.[7] The ship's belt armor was 225 mm (8.9 in) thick amidships, and the main battery turrets were protected by 330 mm (13 in) of armor plate on the faces. The main armored deck was 115 mm (4.5 in) thick, and the conning tower had 270 mm (11 in) thick sides.[10]

Modifications

Dunkerque was modified several times throughout her relatively short career. In 1937, a funnel cap was added and four of the 37 mm guns, which were the Modèle 1925 variant, were removed. These were replaced the following year with new Modèle 1933 guns. The 13.2 mm guns were also rearranged slightly, with the two mounts that were located abreast of the second main battery turret moved further aft. A new 14 m (46 ft) rangefinder was installed in 1940 on the fore tower.[11]

Service history

Construction and working up

Dunkerque was laid down in the Arsenal de Brest, on 24 December 1932, in the Salou graving dock number 4. The hull was completed except for the forward-most 17 m (56 ft) section, since the dock was only 200 m (660 ft) long. She was launched on 2 October 1935 and towed to Laninon graving dock number 8, where the bow was fitted. After that was completed, she was towed out to the Quai d'Armement to have her armament installed and begin fitting-out. Sea trials were carried out, starting on 18 April 1936, at which time her superstructure was not yet complete, and many of her secondary and anti-aircraft guns had not been installed. Two days later, she returned to Brest and had her machinery inspected before further trials through May. Her formal evaluation began on 22 May and continued until 9 October. On 4 February 1937, Dunkerque got underway for shooting trials to test the ship's secondary guns; she had aboard Vice-amiral (VA—Vice Admiral) Morris and Contre-amiral (CA—Rear Admiral) Rivet to observe the tests. Main battery tests were delayed by bad weather from 8 February to 11–14 February. VA François Darlan, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, came aboard on 3 March to observe further gunnery tests. The tests continued through April.[12][13]

VA Devin, the Préfet maritime de la 2e région (Prefect of the 2nd Maritime Region), came aboard Dunkerque on 15 May to take the ship to represent France at the Naval Review marking the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The ship left Brest on 17 May for the review and arrived back on 23 May. She participated in another review off the Île de Sein on 27 May, where she hosted Darlan and Alphonse Gasnier-Duparc, the Naval Minister. Gunnery testing resumed after the review and continued into mid-June, at which point she returned to the shipyard in Brest for further work. In late July, she went to sea for further trials before returning to Brest for additional work that lasted from 15 August to 14 October. In early 1938, the crew prepared the ship for her first major cruise to test her ability to operate at extended ranges, which began on 20 January. The voyage took the ship on a tour of French colonial possessions in the Atlantic; ports of call included Fort-de-France in the Antilles (from 31 January to 4 February) and Dakar, Senegal (from 25 February to 1 March). She returned to Brest on 6 March, thereafter conducting more gunnery testing on 11 March.[14]

Dunkerque underwent another period of equipment inspections and gunnery testing after her return from the voyage that continued into May. From 1 to 4 July, she steamed to the English Channel to visit her namesake town, returning to Brest on 6 July by way of a stay in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue on 4–5 July. George VI and Elizabeth were visiting Boulogne on 16 July, so Dunkerque left Brest that day in company with a group of warships to visit the British monarch there. Dunkerque got underway again on 22 July, bound for Calais, where she saluted the British Royal Family as they left for home. On 1 September, Dunkerque was finally pronounced ready for service and was assigned to the Atlantic Squadron, becoming the flagship of its commander, Vice-amiral d'Escadre (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul.[15]

Prewar service

After entering service, Dunkerque continued her training program, though she was now included in exercises with the rest of the squadron. At the time, the squadron included the three Bretagne-class battleships (the 2nd Battle Division), three cruisers (the 4th Cruiser Division), the aircraft carrier Béarn, and numerous destroyers and torpedo boats. From 18 to 20 October, she took part in maneuvers with Béarn, two torpedo boats, and a sloop off the coast of Brittany. Dunkerque departed Brest on 8 November in company with Béarn and the 4th Cruiser Division for a visit to Cherbourg to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Armistice with Germany that ended World War I. The ships thereafter got underway for training exercises that concluded with a return to Brest on 17 November. Dunkerque then used the wreck of the old battleship Voltaire as a target before returning to the shipyard for maintenance that lasted until 27 February 1939.[16]

The next day, Dunkerque sortied to take part in maneuvers with the Atlantic Squadron off the Brittany coast; another stint in the shipyard for repairs followed from 17 March to 3 April. Gunnery training off the coast of Brittany from 4 to 7 April.[17] In response to the Sudetenland Crisis over Nazi Germany's demand to annex the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, the French naval command sent elements of the Atlantic Squadron, including Dunkerque, three light cruisers, and eight large destroyers, on 14 April to cover the training cruiser Jeanne d'Arc as it returned from a cruise to the French West Indies; at the time, a German squadron centered on the large heavy cruiser Admiral Graf Spee was off the coast of Spain. The ships returned to port two days later.[18] On 24 April, the squadron was joined by Dunkerque's sister ship Strasbourg; the two ships were designated the 1st Battle Division. The ships received identification stripes on their funnels, one for Dunkerque as division leader, and two for Strasbourg.[19][20]

The squadron went to sea again the next day for exercises that lasted until 29 April. On 1 May, Strasbourg joined Dunkerque for the first time for a cruise to Lisbon, Portugal on 1 May, arriving there two days later for a celebration of the anniversary of Pedro Álvares Cabral's discovery of Brazil. The ships left Lisbon on 4 May and arrived in Brest three days later. There, they met a British squadron of warships that were visiting the port at the time. The two Dunkerque-class ships sortied on 23 May in company with the 4th Cruiser Division and three destroyer divisions for maneuvers held off the coast of Great Britain. Dunkerque and Strasbourg then visited a number of British ports, including Liverpool from 25 to 30 May, Oban from 31 May to 4 June, Staffa on 4 June, Loch Ewe from 5 to 7 June, Scapa Flow on 8 June, Rosyth from 9 to 14 June, before stopping in Le Havre, France from 16 to 20 June. The ships arrived back in Brest the next day. The squadron conducted more training off Brittany through July and into early August.[21]

World War II

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the Gulf of Guinea in central Africa. To protect shipping from German commerce raiders, the French created the Force de Raid (Raiding Force), with Dunkerque and Strasbourg as its core. The group, which was under Gensoul's command, also included three light cruisers and eight large destroyers, and was based in Brest. British observers informed the French Navy that the German "pocket battleships" of the Deutschland class had gone to sea in late August, bound for the Atlantic, and that contact with the vessels had been lost. On 2 September, the day after Germany invaded Poland, but before France and Britain declared war, the Force de Raid sortied from Brest to guard against a possible attack by the Deutschlands. Upon learning that the German ships had been spotted in the North Sea, Gensoul ordered his ships to return to port after they met the French passenger liner Flandre in the Azores. The Force de Raid escorted the liner back to port and arrived in Brest on 6 September.[22][23]

By this time, the German raiders had broken out into the Atlantic, so the British and French fleets formed hunter groups to track them down; the Force de Raid was split, with Dunkerque and Strasbourg operating individually as Force L and Force X, respectively. Dunkerque, Béarn, and three cruisers remained in Brest while Strasbourg and two French heavy cruisers joined the British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, based in Dakar. On 22 October, Dunkeque and two cruisers sortied with their destroyer screen to cover Convoy KJ 3 to Kingston, Jamaica, arriving back in Brest three days later. On 25 November, they again went to sea, joining the battlecruiser HMS Hood for a patrol to try to catch the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which had just sunk the British armed merchant cruiser HMS Rawalpindi. While cruising off Iceland, Dunkerque ran into very heavy seas; her bow was repeatedly submerged by the large waves, and she had to slow to 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) to avoid damage. The Germans had by this time returned to port, so the Anglo-French force returned to its ports.[24][25]

On arriving in Brest on 3 December, Dunkerque was docked for repairs to her bow. The experience off Iceland had highlighted defects with her design, including insufficient freeboard and insufficiently strong construction. These problems could not be easily corrected, however, leaving the Dunkerques vulnerable to storm damage.[26] On 11 December, Dunkerque and the cruiser Gloire carried a shipment of part of the Banque de France's gold reserve to Canada. The ships arrived on 17 December and covered a convoy of seven troop ships that was also escorted by the battleship HMS Revenge on the return voyage. While still at sea on 29 December, the convoy met the local escort forces in the Western Approaches, which took over responsibility of the convoy, allowing Dunkerque and Gloire to detach for Brest. After arriving there on 4 January 1940, Dunkerque underwent another period of maintenance that lasted until 6 February. The ship then conducted sea trials and training maneuvers from 21 February to 23 March.[26]

Faced with increasingly hostile posturing by Italy during the spring of 1940, the Force de Raid was dispatched to Mers-el-Kébir on 2 April. Dunkerque, Strasbourg, two cruisers, and five destroyers left that afternoon and arrived three days later. The squadron was quickly ordered to return to Brest just a few days later in response to the German landings in Norway on 9 April. The Force de Raid left Mers-el-Kébir that day and arrived in Brest on the 12th, with the intention that the ships would cover convoys to reinforce Allied forces fighting in Norway. But the threat of Italian intervention continued to weigh on the French command, which reversed the ships' orders and transferred them back to Mers-el Kebir on 24 April; Dunkerque and the rest of the group left that day and arrived on 27 April. They conducted training exercises in the western Mediterranean from 9 to 10 May but saw little activity for the next month. On 10 June, Italy declared war on France and Britain.[27]

Two days later, Dunkerque and Strasbourg sortied to intercept reported German and Italian ships that were incorrectly reported to be in the area. The French had received faulty intelligence that had indicated that the Germans would attempt to force a group of battleships through the Strait of Gibraltar to strengthen the Italian fleet. After the French fleet got underway, reconnaissance aircraft reported spotting an enemy fleet steaming toward Gibraltar. Supposing the aircraft to have spotted the Italian battle fleet steaming to join the Germans, the French increased speed to intercept them, only to realize that the aircraft had in fact located the French fleet. The fleet then returned to port, marking the end of Dunkerque's last wartime operation.[28] On 22 June, France surrendered to Germany following the Battle of France; during the truce negotiations, the French Navy proposed demilitarizing Dunkerque and several other warships in Toulon.[20][29][30] Under the terms of the Armistice, Dunkerque and Strasbourg would remain at Mers-el-Kébir.[31]

Mers-el-Kébir

The only test in battle for Dunkerque came in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July. The British, misinterpreting the terms of the armistice as providing the Germans with access to the French fleet, feared that the ships would be seized and pressed into service against them despite assurances from Darlan that if the Germans attempted to take the vessels, their crews would scuttle them. Prime Minister Winston Churchill then convinced the War Cabinet that the fleet must be neutralized or forced to re-join the war on the side of Britain.[32] The British Force H, commanded by Admiral James Somerville and centered on HMS Hood and the battleships Resolution, and Valiant, arrived off Mers-el-Kébir to coerce the French battleship squadron to join the British cause or scuttle their ships. The French Navy refused, as complying with the demand would have violated the armistice signed with Germany. To ensure the ships would not fall into Axis hands, the British warships opened fire at 17:55. Dunkerque was tied alongside the mole with her stern facing the sea, so she could not return fire.[33][34]

Dunkerque's crew loosed the chains and started to get the ship underway just as the British opened fire; the ship was engaged by HMS Hood. The French gunners responded quickly and Dunkerque fired several salvos at Hood before being hit by four 15-inch (381 mm) shells in quick succession. The first was deflected on the upper main battery turret roof above the right-most gun, though it shoved in the armor plate and ignited propellant charges in the right turret half that asphyxiated all the men in that half; the left half remained operational. The shell itself was deflected off the turret face and failed to explode when it landed around 2,000 m (6,600 ft) away. Fragments of armor plate that had been dislodged by the impact destroyed the run-out cylinder for the right gun, disabling it. The second shell passed through the unarmored stern, penetrating the armor deck and exiting the hull without exploding. Though it did little damage, the shell did cut the control line for the rudder, forcing the ship to use manual control, which hampered the crew's ability to steer the ship as they attempted to get underway.[35]

_-_March_17%252C_1924.jpg.webp)

The third shell hit the ship shortly after 18:00; this projectile struck the upper edge of the belt on the starboard side; since the belt had only been designed to defeat German 28 cm (11 in) shells, the much more powerful British shell easily perforated it. The shell then passed through the handling room for the starboard secondary turret No. III, igniting propellant charges and detonating a pair of 130 mm shells as it did so. The 15 in round then penetrated an internal bulkhead and exploded in the medical storage room. The blast caused extensive internal damage, allowing smoke from the ammunition fire to enter the machinery spaces, which had to be abandoned, though debris from the explosion had jammed the armored doors shut. Only a dozen men were able to escape using a ladder at the forward end of the room. The fourth shell struck the belt aft of the third hit and at the waterline. It also defeated the belt and the torpedo bulkhead and then exploded in boiler room 2, causing extensive damage to the propulsion machinery. Dunkerque rapidly lost speed and then all electrical power; unable to get underway or further resist the British ships, Dunkerque was beached on the other side of Mers-el-Kébir roadstead to prevent her from being sunk.[36][37][38]

The British fire ceased after less than twenty minutes, which limited the damage inflicted; Somerville hoped to minimize the damage done to Franco-British relations.[39][40] Work on the ship began almost immediately; at 20:00, Gensoul ordered the crew to recover the dead and wounded while damage control teams stabilized the ship. Those not engaged in either work—some 800 men—were sent ashore. Half an hour later, he radioed Somerville that the ship had been largely evacuated. By the next morning, the fires had been suppressed and work to plate over the shell holes in the hull had begun. Wounded crewmen had been evacuated to a local hospital. Gensoul expected that the ship would be ready to sail for Toulon for permanent repairs within a few days and informed his superior, Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva (Amiral Sud, the commander of naval forces in North Africa) as much. Esteva in turn issued a statement to that effect to the press in Algeria, which had the unintended effect of informing the British that Dunkerque had not been disabled permanently. Churchill ordered Somerville to return and destroy the ship; Somerville, hoping to avoid civilian casualties now that the ship was beached directly in front of the town of Saint André, secured permission to attack using only torpedo bombers.[41]

The second attack took place on 6 July. A flight of twelve Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, armed with torpedoes modified for use in shallow water, were launched from the carrier HMS Ark Royal in three waves of six, three, and three aircraft. They received an escort of three Blackburn Skua fighters. The French had failed to erect torpedo nets around the ship, and Gensoul, who had hoped to reinforce the idea that the ship had been evacuated, ordered that her anti-aircraft guns not be manned. Three patrol boats were moored alongside to evacuate the remaining crew aboard in the event of another attack, and these vessels were loaded with depth charges. The first wave scored a hit on the patrol boat Terre-Neuve, and though it failed to explode, the hole it punched in her hull caused her to sink in the shallow water. Another torpedo hit the wreck in the second wave and exploded, leading to a secondary explosion of fourteen of her depth charges, which was the equivalent of 1,400 kg (3,100 lb) of TNT, equal to eight Swordfish torpedoes. The explosion caused extensive damage to Dunkerque's bow and likely would have resulted in a magazine detonation had her captain not ordered the magazines be flooded as soon as the Swordfishes appeared. The blast killed another 30, bringing the total killed in both attacks to 210.[42][43]

Dunkerque had been badly damaged in the attack, far more so than the 3 July shelling; some 20,000 t (19,684 long tons) of water had flooded the ship through a 18 by 12 m (59 by 39 ft) hole opened in the hull, and a 40 mm (1.6 in) length of her hull, double bottom, and torpedo bulkhead had been deformed by the blast. The forward armor belt was also distorted and her armored decks had been pushed up. A survey of the damage was conducted on 11 July, but the scale of the damage was beyond what the local shipyard could repair, as it lacked a drydock of sufficient size. Engineers from Toulon were sent to assist the repair work, which began with the fabrication of a 22.6 by 11.8 m (74 by 39 ft) sheet of steel that was bolted over the hull from 19 to 23 August and then sealed with 200 cubic meters (7,100 cu ft) of concrete between 31 August and 11 September. The hull was then pumped dry and re-floated on 27 September, thereafter being towed to a quay in Saint André for further repairs. At this time, torpedo nets were set up around the ship and her anti-aircraft guns were manned. One of the workers accidentally started a serious fire with a welding torch on 5 December.[44]

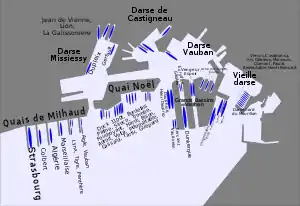

Work continued well into 1941, and in April she conducted stationary trials with her machinery. Her crew returned on 19 May and she was ready to return to Toulon by July, but heavy fighting during the Mediterranean Campaign forced the French to wait to avoid being caught in the cross fire. On 25 January 1942 another fire broke out from a short circuit. Dunkerque was finally ready to cross the Mediterranean on 19 February; she got underway at 04:00, escorted by the destroyers Vauquelin, Tartu, Kersaint, Frondeur, and Fougueux. Some 65 fighters, bombers, and torpedo bombers covered the ships while they made the crossing. Dunkerque reached Toulon at 23:00 on 20 February; her crew was reduced to comply with the terms of the armistice on 1 March, and on 22 June, she entered the large Vauban dock for permanent repairs.[45][46]

Scuttling at Toulon

Repair work proceeded slowly, owing to a shortage of material and labor. After the Wehrmacht occupied the Zone libre in retaliation for the successful Allied landings in North Africa, the Germans attempted to seize the French warships remaining under Vichy control on 27 November. To prevent them from seizing the ships, their crews scuttled the fleet in Toulon, including Dunkerque, which still lay incomplete in the Vauban drydock. Demolition charges were placed on the ship and she was set on fire. Her commanding officer, Capitaine de vaisseau (Captain) Amiel, initially refused to sink his ship without written orders, but was finally convinced to do so by the commanding officer of the nearby light cruiser La Galissonnière.[46][47] Since she was still in the dry dock, the locks had to be opened to flood the ship, which would have taken two to three hours. Since she was in the far side of the dockyard, it took the Germans over an hour to reach the vessel, and in the confusion, they made no attempt to close the locks.[48]

Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to scrap those that were too badly damaged to quickly return to service. The Italians deemed Dunkerque to be a total loss, and so began to dismantle in situ.[48] As part of this process, the ship was deliberately damaged to prevent the French from being able to repair her if she was recaptured; the Italians cut down the main battery guns to render them unusable.[49] The partially scrapped hulk was in turn seized by the Germans when Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943. In 1944, the Germans removed the ship's bow to float her out of the drydock to free up the dock and continue the scrapping process. While in Axis possession, she was bombed several times by Allied aircraft. The hulk was condemned on 15 September 1955 and renamed Q56. Her remains, which amounted to not more than 15,000 tonnes (15,000 long tons; 17,000 short tons), were sold for final demolition on 30 September 1958 for 226,117,000 francs.[46][50]

Footnotes

Notes

- Whitley's Battleships of World War II provides the 1,381 figure, while Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships states the crew numbered 1,431.[7][8] Garzke & Dulin confirm the 1,381 number, and further clarify that the crew was composed of 56 officers, 1,319 enlisted men, and six civilian crew members.[9]

Citations

- Labayle-Couhat, pp. 37–38.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 19–22, 24–26.

- Dumas, pp. 13–15.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 28–29.

- Dumas, pp. 16–17.

- Breyer, p. 433.

- Roberts, p. 259.

- Whitley, p. 45.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 73.

- Garzke & Dulin, pp. 71–72.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 38.

- Dumas, p. 65.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 58.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 58–61.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 61.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 62, 65.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 65.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 65–66.

- Dumas, pp. 67–68.

- Whitley, p. 50.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 66.

- Rohwer, p. 2.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 66, 68.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 68–69.

- Rohwer, pp. 6, 9.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 69.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 70.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 70–71.

- Rohwer, pp. 21, 27, 29–30.

- Dumas, pp. 68–69.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 72.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 72–73.

- Rohwer, p. 31.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 75, 77.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 78–80.

- Whitley, p. 51.

- Dumas, p. 69.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 80–81.

- Dumas, pp. 70–72.

- Whitley, pp. 51–52.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 84.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 84–86, 88.

- Rohwer, pp. 31–32.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 85–86, 88.

- Jordan & Dumas, pp. 88–89.

- Whitley, p. 52.

- Dumas, pp. 74–75.

- Jordan & Dumas, p. 93.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 50.

- Dumas, p. 75.

References

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers 1905–1970. Doubleday and Company. ISBN 0-385-07247-3.

- Dumas, Robert (2001). Les cuirassés Dunkerque et Strasbourg [The Battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg] (in French). Paris: Marine Éditions. ISBN 978-2-909675-75-6.

- Garzke, William H., Jr. & Dulin, Robert O., Jr. (1980). British, Soviet, French, and Dutch Battleships of World War II. London: Jane's. ISBN 978-0-7106-0078-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jordan, John & Dumas, Robert (2009). French Battleships 1922–1956. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-034-5.

- Labayle-Couhat, Jean (1974). French Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7110-0445-0.

- Roberts, John (1980). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 255–279. ISBN 978-0-85177-146-5.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945 – The Naval History of World War Two. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.

External links

![]() Media related to Dunkerque (ship, 1935) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dunkerque (ship, 1935) at Wikimedia Commons