Italian nationality law

Italian nationality law is the law of Italy governing the acquisition, transmission and loss of Italian citizenship. Like many continental European countries it is largely based on jus sanguinis. It also incorporates many elements that are seen as favourable to the Italian diaspora. The Italian Parliament's 1992 update of Italian nationality law is Law no. 91, and came into force on 15 August 1992. Presidential decrees and ministerial directives, including several issued by the Ministry of the Interior, instruct the civil service how to apply Italy's citizenship-related laws.

Acquisition of citizenship

Italian Nationality Law encompasses a comprehensive framework outlining the various routes through which individuals can acquire Italian citizenship. These pathways are tailored to different circumstances and conditions, ensuring a systematic and organized process for citizenship acquisition.

Automatic Acquisition of Italian Citizenship

- Descent: Italian citizenship is automatically conferred to individuals born to an Italian parent, adhering to the principle of jus sanguinis.

- Birth in Italy: Children born on Italian soil to stateless, unknown, or parents unable to transmit their nationality may acquire Italian citizenship, aligning partially with the principle of jus soli.

- Acknowledgement or Legitimation: Children gain Italian citizenship through the acknowledgment or legitimation of an Italian mother or father.

- Minor Children of Citizens: Children without Italian citizenship, including those legally adopted under Italian law, can acquire citizenship if a parent holds Italian citizenship. This provision applies from April 27, 1983.

- Former Citizens: Former Italian citizens who previously renounced citizenship due to naturalization in another country can regain Italian citizenship after two years of residency in Italy. This provision was governed by the Citizenship Law 555 of 1912 until its replacement.

- Vatican Citizens: Individuals relinquishing Vatican citizenship due to circumstances stipulated by the Lateran Treaty of 1929, which would otherwise render them stateless, are eligible for Italian citizenship.[1]

Acquisition through Application

- Continuous Residence: Individuals born in Italy to foreign parents who have continuously resided in Italy from birth to adulthood are eligible to apply for citizenship.

- Denied Applications: Individuals whose citizenship application was denied by administrative offices (Consulates) or those unable to submit the application can seek Italian citizenship through this avenue.[2]

Citizenship through Marriage

- Pre-1983 Marriages: Foreign women who married Italian citizens before April 27, 1983, were automatically granted Italian citizenship.

- Residence and Language Requirements: Spouses of Italian citizens can apply for citizenship through naturalization after two years of legal residence in Italy or three years of residence abroad. This residency requirement is halved if the couple has children. Since December 4, 2018, spouses are also required to demonstrate proficiency in the Italian language at a level of B1 or higher in the EU Common Language Framework.[3]

Naturalization

- A person legally residing in Italy for at least ten years may apply for Italian citizenship through naturalization if they have no criminal record and possess sufficient financial means. The residency period is reduced to three years for grandchildren of Italian citizens and individuals born in Italy, four years for nationals of EU member states, five years for refugees or stateless persons, and seven years for those adopted as children by an Italian citizen. The Italian Nationality Law meticulously outlines these pathways, ensuring a coherent and structured approach to citizenship acquisition while incorporating vital aspects such as language proficiency[4] to promote integration and effective participation in Italian society.[5]

Attribution of citizenship through jus sanguinis

Citizens of other countries descended from an ancestor (parent, grandparent, great-grandparent, etc.) born in Italy may have a claim to Italian citizenship by descent (or, in other words, by derivation according to jus sanguinis citizenship principles).

Italian citizenship is granted by birth through the paternal line, with no limit on the number of generations, or through the maternal line for individuals born on or after 1 January 1948. An Italian citizen may be born in a country whose citizenship is acquired at birth by all persons born there. That person would be born therefore with the citizenship of two (or possibly more) countries. Delays in reporting the birth of an Italian citizen abroad do not cause that person to lose Italian citizenship, and such a report might in some cases be filed by the person's descendants many years after he or she is deceased. A descendant of a deceased Italian citizen whose birth in another country was not reported to Italy may report that birth, along with his or her own birth (and possibly the births of descendants in intermediate generations), to be acknowledged as having Italian citizenship.

A person may only have acquired jus sanguinis Italian citizenship by birth if one or both of that person's parents was in possession of Italian citizenship on the birth date. There is a possibility in the law that the only parent who held Italian citizenship on the birth date of a child born with jus sanguinis Italian citizenship was the mother, who previously acquired the Italian citizenship by marriage to the father, who relinquished his own Italian citizenship before the child was born.

Under certain conditions, a child born with Italian citizenship might later have lost Italian citizenship during his or her infancy. The event could prevent a claim of Italian citizenship by his or her descendants. If the Italian parents of a minor child naturalised in another country, the child may have remained holding Italian citizenship, or else may have lost the Italian citizenship. The children who were exempt from losing their Italian citizenship upon the foreign naturalisation of their parents were in many cases (dual) citizens of other countries where they were born, by operation of the jus soli citizenship laws in those countries.

One must apply through the Italian consulate that has jurisdiction over their place of residence. Each consulate has slightly different procedures, requirements, and waiting times. However, the legal criteria for jus sanguinis citizenship are the same.

Basic Criteria for Acquisition of Citizenship jus sanguinis:

- There were no Italian citizens prior to 17 March 1861, because Italy had not yet been a unified state. Thus the oldest Italian ancestor from whom Italian citizenship is proven to be derived in any jus sanguinis citizenship claim must have been still alive on or after that date.

- Any child born to an Italian citizen parent (including parents also having the right to Italian citizenship jus sanguinis) is ordinarily born an Italian citizen, with the following caveats:

- The Italian parent ordinarily must not have naturalised as a citizen of another country before both the child's birth date and the date 15 August 1992.

- If the child had an Italian mother and a foreign father, the child ordinarily must have been born on or after 1 January 1948. There have been many successful challenges to this date restriction that were brought before the Court of Rome. In their capacity to determine Italian citizenship, officers in Italian consulates and municipalities are bound by the restriction.

- If the Italian parent naturalised as a citizen of another country on or after 1 July 1912, and prior to 15 August 1992, then the child's Italian citizenship survived the parent's loss if the child was already born, and residing in a country whose citizenship he or she additionally held because of that country's jus soli nationality laws. Conversely, if the child was not born in a country whose citizenship was attributed to the child based on jus soli provisions in its nationality law, then the child could lose Italian citizenship by acquiring the citizenship of the naturalising parent. Italy generally does not attribute its citizenship based on jus soli, so an Italian child born in Italy could lose Italian citizenship if his father naturalised.

- If a person reached Italy's legal age of adulthood while possessing Italian citizenship, then that person's holding of Italian citizenship ceased to be conditioned on the subsequent citizenship changes that might occur for that person's parents. So if the Italian parent naturalised as a citizen of another country, then the child's Italian citizenship could survive the parent's loss if he or she reached legal adulthood (age 21 prior to 10 March 1975; age 18 thereafter[6]) prior to the parent's naturalisation.

- If the child's Italian father naturalised as a citizen of another country prior to 1 July 1912, the child's Italian citizenship was not directly impacted by the father's loss if the child reached legal adulthood (age 21) by the time the father naturalised, or else if the child was residing in Italy when the father naturalised.

- Italian citizens naturalising in another country prior to 15 August 1992, while being of legal adult age, typically lost their Italian citizenship at that time.

- Italy has been a participant in the Strasbourg convention on the reduction of cases of multiple citizenship. Children born outside of Italy with the citizenship of a member country may not have been able to hold Italian citizenship by birth because of this convention. The convention has also extended the era when Italians could lose citizenship by foreign naturalisation to dates later than 14 August 1992, if the naturalisation were in a participant country.

"If your Italian ancestor was born in the following regions, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, or Trentino Alto-Adige, in order to apply for the Italian citizenship, you must prove that the ancestor left Italy after July 16, 1920" cit. icapbridging2worlds.com

All conditions above must be met by every person in a direct lineage. There is no generational limit, except in respect to the date of 17 March 1861. Note that if an Italian ancestor naturalised as a citizen of another country independently from his or her parents, and prior to reaching legal Italian adulthood (age 21 prior to 10 March 1975, and age 18 otherwise), then often that ancestor retained Italian citizenship even after the naturalisation and could still pass citizenship on to children. Also, having one qualifying Italian parent—who except in certain situations could only have been the child's father if the birth occurred before 1 January 1948—is sufficient for deriving (inheriting) citizenship, even if the other Italian parent naturalised or otherwise became unable to pass on citizenship. Sometimes that qualifying parent is the foreign-born mother, because foreign women who married Italian men prior to 27 April 1983 automatically became Italian citizens and, in many cases, retained that citizenship even when their Italian husbands later naturalised.

Practical effects

A significant portion of jus sanguinis applicants are Argentines of Italian descent, as Argentina received a large number of Italian immigrants in the 1900s.[7]

The lack of limits on the number of generations of transmission of citizenship means that up to 60 million people, mostly in the Americas, could be entitled to Italian citizenship, a number that is the same as the population of Italy.[7] This large number and the desire for EU citizenship has led to waiting times for a jus sanguinis appointment of up to 20 years at some Italian consulates, particularly in Argentina and Brazil.[7]

Many of these Italians who do receive an Italian passport then use it to live in Spain and had previously used it to live in the United Kingdom when it was still part of the European Union.[7]

The landmark 1992 European Court of Justice case Micheletti v. Cantabria, a case of an Argentine Italian citizen by descent living in Spain whose Italian citizenship was challenged by Spain, established that EU member states were not permitted to distinguish between traditional citizens of a fellow EU state, like Italy, and persons who only had citizenship in another EU state through descent or jus sanguinis.[8]

The long consular waiting lines, combined with the difficulty of locating all the required documents, the fees, and the lack of reason to obtain a second passport for many people, act as a practical limit on the numbers who will actually apply.[7]

Legislative history of Italian citizenship

The Statuto Albertino of 1848

The Statuto Albertino, put forth in 1848 by the Kingdom of Sardinia, was the first basic legal system of the Italian state, formed in 1861. It was not a true constitution, but was essentially an outline of the fundamental principles on which the monarchic rule was based.

Article 24 reads:

"All subjects, whatever be their title or rank, are equal before the law. All enjoy equally the civil and political rights, and are admissible to the civil and military offices, except under circumstances determined in the Law."

This proclaimed equality before the law referred nonetheless only to men, since women were subordinate to the authority of the pater familias. This was held very pertinent in the matter of citizenship, as the subordination of women and also their children to the husband made it so that each event regarding the husband's citizenship would be transmitted to the family. These events could include the loss or reacquisition of citizenship. For example, the family might lose Italian citizenship if the husband naturalised in a foreign state.

1865 Civil Code

The details of Italian citizenship law matters were articulated in title I of book I of the 1865 Civil Code.

Law no. 555 of 1912

On 13 June 1912, Law number 555, concerning citizenship, was passed, and it took effect on 1 July 1912.[9]

Despite the fact that the Statuto Albertino did not make any reference to equality or inequality between the sexes, the precept of the wife's subordination to the husband—one having ancient antecedents—was prevalent in the basic legal system (the legislative meaning). There are numerous examples in the codified law, such as article 144 of the Civil Code of 1939 and, specifically, law number 555 of 13 June 1912 "On Italian Citizenship". Law 555 established the primacy of the husband in the marriage and the subordination of the wife and the children to his events pertinent to his citizenship. It established:

- That jus sanguinis was the guiding principle, and that jus soli was an ancillary possibility.

- The children followed the citizenship of the father, and only in certain cases, the citizenship of the mother. The mother could transmit the citizenship to her children born before 1 January 1948 (the effective date of entry of the Constitution of the Italian Republic) only in the special cases found in paragraph 2 of article 1 of this statute: These cases arose if the father was unknown, if he was stateless, or if the children could not share the father's foreign citizenship according to the law of his county (as in cases where the father belonged to a country where citizenship was possible by jus soli but not by jus sanguinis). In this last situation, the Ministry of the Interior holds that if the child received jus soli citizenship of the foreign country where he was born, the mother's Italian citizenship did not pass to the child, just as in situations where the child received the father's citizenship by jus sanguinis.

- Women lost their original Italian citizenship if they married a foreign husband whose country's laws gave its citizenship to the wife, as a direct and immediate effect of the marriage. (This is a situation under review, since article 10 of this statute providing for the automatic loss of citizenship by marriage is in contrast with the second paragraph of article 8, having global scope, which does not approve of the automatic loss of citizenship by foreign naturalisation. The loss of citizenship under article 8 is not considered automatic because the voluntary acceptance of a new citizenship must have been manifested by the person naturalising for Italian citizenship to be lost pursuant to article 8).

Dual citizenship under law no. 555 of 1912

Of central importance for the diaspora of Italians in many countries, as it relates to the holding of Italian citizenship alongside another citizenship, is article 7 of law number 555 of 1912. The provisions of this article gave immunity to some living Italian children from the citizenship events of their fathers. If the child was born to an Italian father in a jus soli country, the child was born with the Italian citizenship of the father and also with the citizenship of the country where he or she was born. That is to say that the child was born as a dual citizen. Children born with dual citizenship in this form were allowed to maintain their dual status in case the father naturalised later, thus parting with his Italian citizenship. Moreover, Italy has not imposed limitations on the number of generations of its citizens who might be born outside Italy, even as holders of citizenship foreign to Italy.

Article 7 reads:[10]

"Except in the case of special provisions to be stipulated by international treaties, an Italian citizen born and residing in a foreign nation, which considers him to be a citizen of its own by birth, still retains Italian citizenship, but he may abandon it when he becomes of age or emancipated."

Since Italian laws in this time were very sensitive to gender, it remains to be stated that the benefit of article 7 was extended to both male and female children. A girl of minor age could keep her Italian citizenship in accordance with article 7 after the naturalisation of her father—but she still might not be able to pass her own citizenship to her children, particularly if they were born before 1948.

Law 555 of 1912 contains a provision causing the Italian children of Italian widows to retain their Italian citizenship if the widow should acquire a new citizenship by remarrying, to be found in article 12. The children concerned could keep their Italian citizenship even if they received a new one by derivation from the mother when the remarriage occurred.

Foreign women contracting marriage with Italian men before 27 April 1983 automatically became Italian citizens. If a woman's acquisition of Italian citizenship by marriage did not produce an effect upon the woman's citizenship in her country of origin, she was therefore a dual citizen. Article 10 of law 555 of 1912 provided that a married woman could not assume a citizenship different from that of her husband. If an Italian woman acquired a new citizenship while her husband remained Italian, she was a dual citizen, and law 555 of 1912 was not cognisant of her new status in the state where she acquired citizenship during her marriage.

Loss of Italian citizenship under law no. 555 of 1912

Italian citizenship could be lost:

- By a man or woman, being of competent legal age (21 years if before 10 March 1975 or 18 years if after 9 March 1975), who of his or her own volition naturalised in another country and resided outside of Italy. (article 8) Italian citizen women married to Italian citizen husbands could not lose their citizenship if the husband's Italian citizenship was retained. (article 10)

- By the minor and unemancipated child—without the immunities from loss to be found in articles 7 and 12 (child with jus soli citizenship or child of remarried widow with consequent new citizenship)—who, residing outside of Italy, held a non-Italian citizenship and lived with a father (or mother if the father was dead) whose Italian citizenship was also lost. (article 12)

- By the woman whose Italian citizenship was a consequence of marriage to an Italian citizen, if upon becoming widowed or divorced, she returned to (or remained in) the country of her origin to live there as a citizen. (article 10) This scenario of loss was possible only before the date 27 April 1983.

- By the citizen who accepted employment with or rendered military service to a foreign state, and was expressly ordered by the Italian government to abandon this activity before a deadline, and still persisted in it after the said deadline. (article 8) This kind of loss was rather uncommon, and could only occur if the Italian government contacted the citizen whose abandonment of service to a foreign government was demanded.

Loss of Italian citizenship carried with it the inability to pass Italian citizenship automatically to children born during the period of not holding the citizenship. Still, Italian citizenship could sometimes be acquired by children of former citizens reacquiring the citizenship. Because law 555 of 1912 underwent revision to meet the republican constitution's requirement that the sexes be equal before the law, a determination of citizenship for a child involves an analysis of the events of both parents and possibly the ascendants of both.

The 1948 Constitution of the Republic

The constitution of the Italian Republic entered into effect on 1 January 1948. With the Salerno Pact in April 1944, stipulated between the National Liberation Committee and the Monarchy, the referendum on being governed by a monarchy or a republic was postponed until the end of the war. The 1848 constitution of the Kingdom of Italy was still formally in force at this time, since the laws that had limited it were, to some extent, abolished on 25 July 1943 (date of the collapse of the fascist regime). The referendum was held on 2 June 1946. All Italian men and women 21 years of age and older were called to vote on two ballots: one of these being the Institutional Referendum on the choice between a monarchy and a republic, the other being for the delegation of 556 deputies to the Constituent Assembly.

The current Italian constitution was approved by the Constituent Assembly on 22 December 1947, published in the Official Gazette on 27 December 1947, and entered into effect on 1 January 1948. The original text has undergone parliamentary revisions.

A Democratic Republic was instituted, based on the deliberations and sovereignty of the people. Individual rights were recognised, as well as those of the body public, whose basis was the fulfilment of binding obligations of political, economic, and social solidarity (articles 1 and 2).

The fundamental articles that were eventually used to support new arguments concerning citizenship are as follows:

Article 3, a part of the constitution's "Fundamental Principles", has two clauses.

- The first clause establishes the equality of all citizens: "All citizens have equal social dignity and are equal before the law, without distinction of sex, race, language, religion, political opinions, personal and social conditions."

- The second clause, supplementary to the first and no less important, adds: "It is the duty of the Republic to remove those obstacles of an economic and social nature which, really limiting the freedom and equality of citizens, impede the full development of the human person and the effective participation of all workers in the political, economic and social organisation of the country."

Article 29, under Title II, "Ethical and Social Relations", reads: "The Republic recognises the rights of the family as a natural society founded on matrimony." The second clause establishes the equality between spouses: "Matrimony is based on the moral and legal equality of the spouses within the limits laid down by law to guarantee the unity of the family."

Another article of fundamental importance here is article 136, under Title VI, "Constitutional Guarantees - Section I - The Constitutional Court", reading as follows: "When the Court declares the constitutional illegitimacy of a law or enactment having the force of law, the law ceases to have effect from the day following the publication of the decision." Moreover, relating to this article, still with pertinence to citizenship, the second clause is very important: "The decision of the Court shall be published and communicated to the Houses and to the regional councils concerned, so that, wherever they deem it necessary, they shall act in conformity with constitutional procedures."

Decisions of the Constitutional Court and laws enacted in consequence

In summary, law 555 of 1912 has been superseded by new laws and rulings so that:

- The child born on or after 1 January 1948 to an Italian man or woman is to be considered Italian by birth (except as provided in some treaties).

- An Italian woman's marriage to an alien, or her husband's loss of Italian citizenship, has not caused the woman's Italian citizenship to change if the marriage or husband's naturalisation came on or after 1 January 1948. If the same event were prior to 1 January 1948, the Italian consulates and municipalities may not deem her citizenship uninterrupted. In the latter case, the possibility remains that the matter of her continued holding of Italian citizenship will be confirmed in court.

- All minor children of at least one Italian citizen parent, including an adoptive parent, as of the date 27 April 1983 who did not already have Italian citizenship received Italian citizenship on this date.

- Also beginning on 27 April 1983, the Italian law ceased to prescribe automatic Italian citizenship for foreign women marrying Italian citizen husbands.

Decision no. 87 of 1975

This decision, in summary, finds that it is unconstitutional for women to be deprived of their Italian citizenship if they acquired a new citizenship automatically by marriage. Italy has officially expressed that the benefit of this decision extends retroactively to marriages as early as 1 January 1948.

The constitution of the Republic stayed unimplemented, in the matter of citizenship, from the time of its enactment until the year 1983. Notwithstanding the equality determined by articles 3 and 29 of the constitution, the Parliament did not put forth any law modifying the absence of code law which would allow the child of an Italian citizen mother and an alien father to have Italian citizenship by jus sanguinis.

The decision rendered on 9 April 1975, number 87, by the Constitutional Court, declared the unconstitutionality of article 10, third paragraph, in the part which foresaw a woman's loss of citizenship independently from her free will.

Among the essential points of the decision, it was pointed out that article 10 was inspired by the very widespread concept in 1912 that women were legally inferior to men, and as individuals, did not have full legal capacity. Such a concept was not represented by, and moreover was in disagreement with, the principles of the constitution. In addition, the law, by stipulating a loss of citizenship reserved exclusively for women, undoubtedly created an unjust and irrational disparity in treatment between spouses, especially if the will of the woman was not questioned or if the loss of citizenship occurred contrarily to her intentions.

Law no. 151 of 1975

In summary, this law impacts citizenship by confirming decision 87 of 1975 for marriages happening after its entry into effect, and authorizing women who lost the Italian citizenship automatically by receiving a new citizenship as a consequence of marriage to reacquire it with a petition. While this law did not state the capability of decision 87/1975 to retroact, the decision's accepted retroactive application back as far as 1 January 1948 is on the merit of the constitution. In the larger picture, law 151 of 1975 was an extensive remodeling of family law in Italy.

As a result of the finding of unconstitutionality in decision 87/1975, within the scope of Italy's reform of family law in 1975, article 219 was introduced into law 151 of 1975 which sanctioned for women the "reacquisition" (more properly, recognition) of citizenship. Article 219 reads:

"The woman who, by effect of marriage to an alien or because of a change in citizenship on the part of her husband, has lost the Italian citizenship before the entry of this law into effect, may reacquire it with a declaration made before the competent authority in article 36 on the provisions of implementing the civil code. Every rule of the law 555 of 13 June 1912 which is incompatible with the provisions of this present law stands repealed."

The term "reacquisition" appears improper inasmuch as the Constitutional Court's decision pronounced that the citizenship was never lost by the women concerned, and that there was never a willingness to this end on their part, and thus the term "recognition" seems more proper academically and legally.

Decision no. 30 of 1983

Decision number 30 of 1983 is the finding that transmitting Italian citizenship by birth is a constitutional right of women, and the decision retroacts for births beginning as early as 1 January 1948. The mother must have been holding Italian citizenship when the child was born for the transmission to occur as a consequence of this rule.

Decision number 30 was pronounced on 28 January 1983, deposited in chancellery on 9 February 1983, and published in "Official Gazette" number 46 on 16 February 1983. The question of unconstitutionality of article 1 of law 555 of 1912 was posed "where it does not foresee that the child of an Italian citizen mother having kept her citizenship even after her marriage to a foreigner, also has Italian citizenship". The decision determined that the first clause of article 1 of this law was in clear contrast with the constitution's articles 3 (first paragraph—equality before the law without regard to sex, etc.) and 29 (second paragraph—moral and juridical parity between spouses). The Constitutional Court not only declared article 1 of law 555 of 13 June 1912 unconstitutional where it did not foresee the Italian citizenship of the child of an Italian citizen mother; but also article 2 of the same law where it sanctions a child's acquisition of a mother's citizenship only in limited cases, since thereafter those limitations were lifted and mothers could generally pass Italian citizenship to their children.

Opinion no. 105 of 1983 from the State Council

The opinion number 105 of 15 April 1983; given by the State Council, Section V, in a consultative session; determined that by effect of Decision 30 of 1983 by the Constitutional Court, the individuals born to an Italian citizen mother only as far back as 1 January 1948 could be considered Italian citizens, on the premise that the effectiveness of the decision could not retroact further than the moment when the contradiction between the old law and the new constitution emerged, which was 1 January 1948, the date of the constitution's entry into effect.

Law no. 123 of 1983

This law granted automatic Italian citizenship to minor children (under age 18) of at least one parent holding Italian citizenship on its entry date into effect (27 April 1983). The law ended the practice of granting automatic citizenship to women by marriage. The law gave an obligation to dual citizens to opt for a single citizenship while 18 years of age.

On 21 April 1983, law number 123 was passed, which established that all minor children of an Italian citizen father or mother, including an adoptive parent, were Italian citizens by birth.[11] In the case of dual citizenship, the child was required to select a single citizenship within one year after reaching the age of majority (article 5) — unless the non-Italian citizenship was acquired through birth in a jus soli country, according to a 1990 Council of State opinion.[11] The law is understood to have extended Italian citizenship to all minor children of Italian citizens at the moment of the law's entry into effect, even if the children were adopted.[11] The same law repeals the prior rule prescribing automatic acquisition of Italian citizenship jure matrimonis by alien women who contracted marriage with an Italian citizen husband. Thus since the date of entry into force (27 April), the equality of foreign spouses before the Italian law was instituted, and the cardinal principle of acquisition of citizenship through one's expression of free will was reasserted.

Loss of Italian citizenship under law no. 123 of 1983

With the entry of law 123 of 1983 into effect on 27 April 1983, Italy instituted a requirement of selecting a single citizenship among those Italians with multiple citizenship reaching the age of majority on or after 27 April 1983. The selection was due within one year. If the selection of Italian citizenship was not made, there was the potential for the Italian citizenship to be lost.

The government's orientation toward this rule is that those dual citizens whose foreign nationality came by birth in states attributing their jus soli citizenship to them were exempt from the requirement, because this law did not repeal the still effective article 7 of law 555 of 1912.[11] The government has also clarified that children born to Italian mothers foreign naturalised as an automatic result of a marriage contracted on or after 1 January 1948 are also exempt from the requirement.

The requirement was repealed on 18 May 1986, and so it was given only to people born between 27 April 1965 and 17 May 1967. Between 18 May 1986 and 14 August 1994, people subject to the requirement were entitled to make belated selections of Italian citizenship, or amend previously made selections of foreign citizenship.

Italy's current citizenship laws

Law no. 91 of 1992

| Italian Citizenship Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| Italian Parliament | |

| |

| Enacted by | Government of Italy |

| Status: Current legislation | |

Law number 91, passed on 5 February 1992, establishes that the following persons are citizens by birth:

- a) The child of a citizen father or mother.

- b) Whoever is born within the Republic's territory if both parents are stateless or unknown, or if the child's citizenship does not follow that of the parents, pursuant to the law of their country. (article 1, first paragraph).

By paragraph 2, foundlings recovered in Italy are citizens by birth if it cannot be proven that these persons are in possession of another citizenship. Article 3 partially restates the text contained in article 5 of law 123 of 1983 where it establishes that an adoptive child of an Italian citizen is Italian, even if the child is of foreign origin, and even if the child was born before the passing of the law. It has expressly established retroactivity in this situation.

This is notwithstanding the fact that the law otherwise precludes its own retroactive application in article 20, which provides that "...except as expressly provided, the citizenship status acquired prior to the present law is not altered, unless by events after its date of entry into force".

This provision, in concert with opinion number 105 of 15 April 1983, has provided that children of an Italian citizen mother and an alien father born before 1 January 1948 (date of the republican constitution's entry into force) remain subject to the old law 555 of 13 June 1912, despite the Constitutional Court's pronouncement of unconstitutionality in decision 30 of 1983.

Additionally, law 91 of 1992 allows the possession of multiple citizenships, previously prohibited in article 5 of law 123 of 1983 for those Italians acquiring a new citizenship. This allowance of keeping Italian citizenship is not applicable in all cases of an Italian acquiring foreign citizenship, because Italy has maintained treaties with some states to the effect that an Italian naturalising in one of those states could lose Italian citizenship automatically. Law 91 of 1992 leaves those agreements in effect. (article 26) Furthermore, law 91 of 1992 rules that persons who obtain Italian citizenship do not need to renounce to their earlier citizenship, provided the dual nationality is also permitted by the other concerned state.

Laws coming after 1992 have altered access to citizenship extending it to some categories of citizens who for historical reasons, in connection with war events, were still excluded.

These more recent laws follow:

1) Law no. 379 of 14 December 2000 "Provisions for the recognition of Italian citizenship for the persons born and resident in the territories belonging to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and their descendants". (Published in the Official Gazette no. 295 on 19 December 2000)

Law 379/2000 contained provisions to recognize Italian citizenship for those persons who were born and residing in Italy's annexed territories from the Austro-Hungarian Empire prior to 15 July 1920. The recognition was available also to their descendants. Recognition of Italian citizenship under law 379/2000 was given only to applicants, and the provisions expired in December 2010.

2) Law no. 124 of March 2006 "Changes to law number 91 of 5 February 1992 concerning the recognition of Italian citizenship for nationals of Istria, Fiume, and Dalmatia and their descendants". (Published in the Official Gazette no. 73 on 28 March 2006)

Law 124/2006 allows individuals who were Italian citizens residing in territories ceded from Italy to Yugoslavia at the time of their cession to reclaim Italian citizen status. It gives the ability to claim Italian citizen status to those people with knowledge of Italian language and culture who are lineal descendants of the eligible persons who were residing in those regions.

In more recent times, reforms to the citizenship law favouring immigrants from outside of the European Union were discussed. These immigrants currently may apply for citizenship after the completion of ten years of residency in the territory of the republic.

Many aspects remain unresolved, such as the recognition of citizenship status for descendants of an Italian woman who before 1948 had married a foreign husband and lost Italian citizenship on account of her marriage. These cases have created a dual system for recognition of citizenship: While the descendants by a paternal line have no impediments to the recognition of their citizenship status—even if the ascendant emigrated in 1860 (before Italy formed a state); the descendants of an Italian woman—even if she was from the same family—today still find themselves precluded from reacquiring Italian citizenship, and their only possible remedy is to appear before an Italian judge.

Transmission of Italian citizenship along maternal lines

Decision no. 4466 of 2009 from the Court of Cassation (final court of appeals)

The United Sections, reversing its position in decision number 3331 of 2004, has established that, by effect of decisions 87 of 1975 and 30 of 1983, the right to Italian citizenship status should be recognised for the applicant who was born abroad to the son of an Italian woman married to an alien within the effective period of law 555 of 1912 who was in consequence of her marriage deprived of Italian citizenship.

Though partaking of the existing principle of unconstitutionality, according to which the pronouncement of unconstitutionality of the pre-constitutional rules produces effects only upon the relations and situations not yet concluded as of the date 1 January 1948, not being capable of retroacting earlier than the constitution's entry into force; the Court affirms that the right of citizenship, since it is a permanent and inviolable status except where it is renounced on the part of the petitioner, is justifiable at any time (even in the case of the prior death of the ascendant or parent of whoever derives the recognition) because of the enduring nature, even after the entry into force of the constitution, of an illegitimate privation due to the discriminatory rules pronounced unconstitutional.

Effects of decision no. 4466 of 2009 from the Court of Cassation on jurisprudence

After this 2009 decision, the judges in the Court of Rome (Tribunale di Roma) awarded, in more than 500 cases, Italian citizenship to the descendants of a female Italian citizen, born before 1948; and to the descendants of an Italian woman who had married a non-Italian citizen before 1948. As the Italian Parliament has not coded this decision from Cassation into law, it is not possible for these descendants to obtain jus sanguinis citizenship, making the pertinent application before a consulate or a competent office of vital and civil records in Italian municipalities. For these kind of descendants of Italian women the possibility of receiving recognition of Italian citizenship therefore only remains by making a case in the Italian Court.

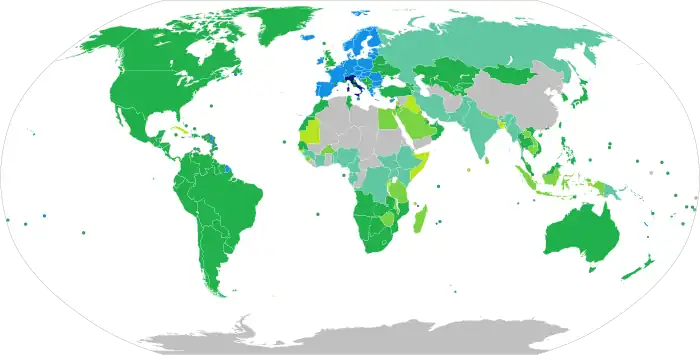

Travel freedom of Italian citizens

Visa requirements for Italian citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of Italy. In 2017, Italian citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 174 countries and territories, ranking the Italian passport 3rd in terms of travel freedom (tied with American, Danish, Finnish and Spanish passports) according to the Henley visa restrictions index.[12] Additionally, the World Tourism Organization also published a report on 15 January 2016 ranking the Italian passport 1st in the world (tied with Denmark, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg, Singapore and the United Kingdom) in terms of travel freedom, with the mobility index of 160 (out of 215 with no visa weighted by 1, visa on arrival weighted by 0.7, eVisa by 0.5 and traditional visa weighted by 0).[13]

The Italian nationality is ranked eighth, together with Finland, in Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Visa Restrictions Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, in addition, to travel freedom on internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.[14]

Dual citizenship

According to Italian law, multiple citizenship is explicitly permitted under certain conditions if acquired on or after 16 August 1992.[15] (Prior to that date, Italian citizens with jus soli citizenship elsewhere could keep their dual citizenship perpetually, but Italian citizenship was generally lost if a new citizenship was acquired, and the possibility of its loss through a new citizenship acquisition was subject to some exceptions.) Those who acquired another citizenship after that date but before 23 January 2001 had three months to inform their local records office or the Italian consulate in their country of residence. Failure to do so carried a fine. Those who acquired another citizenship on or after 23 January 2001 could send an auto-declaration of acquisition of a foreign citizenship by post to the Italian consulate in their country of residence. On or after 31 March 2001, notification of any kind is no longer necessary.

Citizenship of the European Union

Because Italy forms part of the European Union, Italian citizens are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament. [16] When in a non-EU country where there is no Italian embassy, Italian citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[17][18] Italian citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[19]

Citizenship fee

Since 2014 all applications by people aged 18 or over asking for recognition of Italian citizenship are subject to a payment of a €300 fee (Law n. 66, 24 April 2014 and Law n. 89, 23 June 2014). This was passed by the Renzi Cabinet led by Matteo Renzi.[20]

See also

References

- "Lateran Treaty" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- "Italian Citizenship Assistance: What's Best 2020 Solution?". Studio Legale Bersani | Diritto Civile & Immigrazione Verona | Cittadinanza Italiana Verona. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- "Ways to become an Italian citizen" (in Italian and English). Embassy of Italy in Washington, DC. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- dualital7 (15 May 2021). "How To Obtain Italian Citizenship by Residency | IDC". Italian Dual Citizenship. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- "Ciudadanía italiana por residencia – Cavalcanti de Albuquerque" (in European Spanish). Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- "Circolare n. 9 del 04.07.2001 - Cittadinanza: assetto normativo precedente all'entrata in vigore della legge n. 91/1992. Linee applicative ed interpretative" (PDF). Italian Ministry of the Interior. 4 July 2001. Footnote 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Mateos, Pablo. "External and Multiple Citizenship in the European Union. Are 'Extrazenship' Practices Challenging Migrant Integration Policies?". Princeton University. pp. 20–23. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Moritz, Michael D. (2015). "The Value of Your Ancestors: Gaining 'Back-Door' Access to the European Union Through Birthright Citizenship". Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law. 26: 239–240.

- "Legge 13 giugno 1912, n.555 sulla cittadinanza italiana" (in Italian). Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Legge 13 giugno 1912, n.555 sulla cittadinanza italiana" [Law N. 555, on Italian citizenship] (PDF) (in Italian). Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Ministero dell'Interno. "La Cittadinanza Italiana: La Normative, Le Procedure, Le Circolari". pp. 32–33. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012.

- "Global Ranking - Visa Restriction Index 2017" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Visa Openness Report 2016" (PDF). World Tourism Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Cittadinanza". esteri.it. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Italy". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Recognition of the Italian Citizenship". Consulate General of Italy in New York. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

External links

Further reading

- "Law no. 555 of 1912". US Department of Labor, Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of Labor for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1924. Hathi Trust Digital Library. p. 215. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Donati, Sabina (2013). A political history of national citizenship and identity in Italy, 1861-1950. Stanford University Press. p. 424. ISBN 9780804787338.