Italian cruiser Puglia

Puglia was a protected cruiser of the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy). She was the last of six Regioni-class ships, all of which were named for regions of Italy. She was built in Taranto between October 1893 and May 1901, when she was commissioned into the fleet. The ship was equipped with a main armament of four 15 cm (5.9 in) and six 12 cm (4.7 in) guns, and she could steam at a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

Puglia in 1901 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Puglia |

| Namesake | Apulia (Italian: Puglia) |

| Builder | Arsenal of Taranto |

| Laid down | October 1893 |

| Launched | 22 September 1898 |

| Commissioned | 26 May 1901 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 22 March 1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Regioni-class protected cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 88.25 m (289 ft 6 in) |

| Beam | 12.13 m (39 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 5.45 m (17 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range | 2,100 nmi (3,900 km; 2,400 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 213–278 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Puglia served abroad for much of her early career, including periods in South American and East Asian waters. She saw action in the Italo-Turkish War in 1911–1912, primarily in the Red Sea. During the war she bombarded Ottoman ports in Arabia and assisted in enforcing a blockade on maritime traffic in the area. She was still in service during World War I; the only action in which she participated was the evacuation of units from the Serbian Army from Durazzo in February 1916. During the evacuation, she bombarded the pursuing Austro-Hungarian Army. After the war, Puglia was involved in the occupation of the Dalmatian coast, and in 1920 her captain was murdered in a violent confrontation in Split with Croatian nationalists. The old cruiser was sold for scrapping in 1923, but much of her bow was preserved at the Vittoriale degli italiani museum.

Design

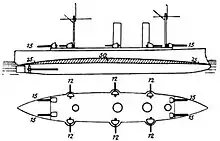

Puglia was slightly larger than her sister ships. 88.25 meters (289 ft 6 in) long overall and had a beam of 12.13 m (39 ft 10 in) and a draft of 5.45 m (17 ft 11 in). Specific displacement figures have not survived for individual members of the class, but they displaced 2,245 to 2,689 long tons (2,281 to 2,732 t) normally and 2,411 to 3,110 long tons (2,450 to 3,160 t) at full load. The ships had a ram bow and a flush deck. Each vessel was fitted with a pair of pole masts. She had a crew of between 213 and 278.[1]

Her propulsion system consisted of a pair of vertical triple-expansion steam engines that drove two screw propellers. Steam was supplied by four cylindrical fire-tube boilers that were vented into two funnels.[1] Puglia's engines were rated to produce a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) from 7,000 indicated horsepower (5,200 kW);[2] specific horsepower figures for the ship have not survived, but members of her class had an output of 6,842 to 7,677 indicated horsepower (5,102 to 5,725 kW). The ship had a cruising radius of about 2,100 nautical miles (3,900 km; 2,400 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

Puglia was armed with a main battery of four 15 cm (5.9 in) L/40 guns mounted singly, with two side by side forward and two side by side aft. A secondary battery of six 12 cm (4.7 in) L/40 guns were placed between them, with three on each broadside. Close-range defense against torpedo boats consisted of eight 57 mm (2.2 in) guns, eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and a pair of machine guns. She was also equipped with two 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. Puglia was protected by a 25 mm (0.98 in) thick deck, unlike her sisters which all had decks twice as thick. Her conning tower had 50 mm (2 in) thick sides.[1]

Service history

Puglia was built by the new Regia Marina shipyard in Taranto, the first major warship to be built there. Her keel was laid down in October 1893, and she was launched on 22 September 1898. Fitting-out work proved to be a lengthy process, and she was not ready for service until 26 May 1901. By this time, her design was over ten years old and the ship was rapidly becoming obsolescent;[3] in comparison, Germany had already commissioned the world's first light cruisers, the Gazelle class, which were significantly faster and better armed. This new type of ship rapidly replaced protected cruisers like Puglia.[4][5]

Puglia was immediately deployed to East Asian waters following her commissioning. In July, she was in Australia during the visit of the British Prince George, son of then-King Edward VII.[6] The ship was still on the China station as of 1904.[7] Puglia was present in Rio de Janeiro in January 1908 when the Great White Fleet arrived in the port. She greeted the American fleet with a 15-gun salute. The German cruiser SMS Bremen was also moored in the harbor at the time, as was the Brazilian fleet.[8]

Italo-Turkish War

At the outbreak of Italo-Turkish War in September 1911, Puglia was stationed in eastern Africa, where Italy had colonies in Eritrea and Somaliland. She was joined there by her sisters Elba and Liguria and the cruisers Piemonte and Etna. Puglia and the cruiser Calabria, which had recently arrived from Asian waters, bombarded the Turkish port of Aqaba on 19 November to disperse a contingent of Ottoman soldiers there. Hostilities were temporarily ceased while the British King George V passed through the Red Sea following his coronation ceremony in India—the ceasefire lasted until 26 November.[9] After resuming operations in the northern Red Sea, Puglia caught the Ottoman gunboat Haliç off Aqaba on 5 December and damaged her, forcing her crew to scuttle the vessel later. On 16 December, she intercepted the steamer Kayseri leaving the Suez Canal, bound for Kunfuda with a load of coal for the Ottoman gunboats stationed there.[10]

In early 1912, the Italian Red Sea fleet searched for a group of seven Ottoman gunboats thought to be planning an attack on Eritrea, though they were in fact immobilized due to a lack of coal. Puglia and Calabria carried out diversionary bombardments against Jebl Tahr, and Al Luḩayyah, while Piemonte and the destroyers Artigliere and Garibaldino searched for the gunboats. On 7 January, they found the gunboats and quickly sank four in the Battle of Kunfuda Bay; the other three were forced to beach to avoid sinking as well.[11][12] Puglia and the rest of the Italian ships returned to bombarding the Turkish ports in the Red Sea before declaring a blockade of the city of Al Hudaydah on 26 January. The cruiser fleet in the Red Sea then began a campaign of coastal bombardments of Ottoman ports in the area. A blockade was proclaimed of the Ottoman ports, which included Al Luḩayyah and Al Hudaydah. The Ottomans eventually agreed to surrender in October, ending the war.[13]

World War I

_-_DSC02086.JPG.webp)

Italy declared neutrality at the start of World War I, but by July 1915, the Triple Entente had convinced the Italians to enter the war against the Central Powers. Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, the Italian naval chief of staff, believed that Austro-Hungarian submarines could operate too effectively in the narrow waters of the Adriatic, which could also be easily seeded with minefields. The threat from these underwater weapons was too serious for him to use the fleet in an active way. Instead, Revel decided to implement blockade at the relatively safer southern end of the Adriatic with the main fleet, while smaller vessels, such as the MAS boats, conducted raids on Austro-Hungarian ships and installations.[14]

The closest Puglia came to engaging a hostile vessel came on 27 January 1915, when while patrolling off Durazzo, she encountered the Austro-Hungarian scout cruiser Novara, but the Austro-Hungarian ship retreated without either vessel firing a shot.[15] In late February 1916, Puglia, the cruiser Libia, and the auxiliary cruisers SS Cittá di Siracusa and SS Cittá di Catania covered the withdrawal of elements of the Serbian Army from Durazzo. On 25 February, the Italian vessels entered the harbor to bombard Austro-Hungarian forces to delay their advance while Allied transport vessels evacuated soldiers from the city. The battle between the Italian cruisers and Austro-Hungarian artillery batteries continued through the following day, and late on the 26th, the transports completed the embarkation of Italian and Serbian troops before departing for Valona. Shortly before departing, Puglia opened fire on the warehouses storing munitions in the harbor, setting them on fire to destroy the equipment stored there.[16][17] She was converted into a minelayer later that year. She entered service in this role on 1 July, and she remained on active duty through the early 1920s.[3]

After the war, Puglia had been assigned to patrol the Dalmatian coast. On 11 July 1920, men from the ship became involved in the unrest in Split. During a violent confrontation with a group of Croats, the ship's captain and a sailor were shot and killed.[18] Puglia was sold for scrapping on 22 March 1923.[1] While the ship was being dismantled, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini donated the ship's bow section to the writer and ardent nationalist Gabriele D'Annunzio, who had it installed at his estate as part of the Vittoriale degli italiani museum.[19]

Notes

- Fraccaroli, p. 349.

- Weyl, p. 34.

- Fraccaroli, pp. 349–350.

- Fraccaroli, p. 258.

- Fitzsimons, p. 1764.

- Twentieth Century Impressions of Western Australia, p. 57.

- Garbett, p. 1429.

- Matthews, p. 90.

- Beehler, pp. 10, 47–48.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 15.

- Robinson, pp. 166–167.

- Beehler, p. 51.

- Beehler, pp. 51, 60, 70, 95.

- Halpern, pp. 140–142, 150.

- Halpern, p. 158.

- Hurd, pp. 69–74.

- Klein, p. 389.

- The Contemporary Review, p. 514.

- Domenico, p. 54.

References

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Domenico, Roy Palmer (2002). Remaking Italy in the Twentieth Century. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9637-5.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1978). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. Vol. 16. New York: Columbia House. ISBN 0-8393-6175-0.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1979). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 334–359. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1904). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII: 1418–1434.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Hurd, Archibald (1918). Italian Sea-power and the Great War. London: Constable & Company.

- Klein, Henri P. (1920). "War, European – Italian Campaign". The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. XXVIII. New York: The Encyclopedia Americana Corporation.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Matthews, Franklin (1909). With the Battle Fleet: Cruise of the Sixteen Battleships of the United States Atlantic Fleet from Hampton Roads to the Golden Gate, December, 1907 – May, 1908. New York: B. W. Huebsch. OCLC 12575552.

- Robinson, C. N. (1912). Hythe, Thomas (ed.). "The Turco-Italian War". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 146–174.

- The Contemporary Review. London: A. Strahan. 118. 1920. OCLC 1564974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - Twentieth Century Impressions of Western Australia. Perth: P. W. H. Thiel. 1901. OCLC 5747592.

- Weyl, E. (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 17–60.