Italian wine

Italian wine is produced in every region of Italy. Italy is the world's largest producer of wine, with an area of 702,000 hectares (1,730,000 acres) under vineyard cultivation, and contributing a 2013–2017 annual average of 48.3 million hl of wine. In 2018 Italy accounted for 19 per cent of global production, ahead of France (17 per cent) and Spain (15 per cent).[1] Italian wine is both exported around the world and popular domestically among Italians, who consume an average of 42 litres per capita, ranking fifth in world wine consumption.

The origins of vine-growing and winemaking in Italy has been illuminated by recent research, stretching back even before the Phoenician, Etruscans and Greek settlers, who produced wine in Italy before the Romans planted their own vineyards.[2] The Romans greatly increased Italy's viticultural area using efficient viticultural and winemaking methods.[3]

History

Vines have been cultivated from the wild Vitis vinifera grape for millennia in Italy. It was previously believed that viticulture had been introduced into Sicily and southern Italy by the Mycenaeans,[4] as winemaking traditions are known to have already been established in Italy by the time the Phoenician and Greek colonists arrived on Italy's shores around 1000–800 BC.[5][6] However, archeological discoveries on Monte Kronio in 2017 revealed that viticulture in Sicily flourished at least as far back as 4000 BC — some 3,000 years earlier than previously thought.[7] Also on the peninsula, traces of Bronze Age and even Neolithic grapevine management and small-scale winemaking might suggest earlier origins than previously thought.[8]

Under Ancient Rome large-scale, slave-run plantations sprang up in many coastal areas of Italy and spread to such an extent that, in AD 92, emperor Domitian was forced to destroy a great number of vineyards in order to free up fertile land for food production.

During this time, viticulture outside of Italy was prohibited under Roman law. Exports to the provinces were reciprocated in exchange for more slaves, especially from Gaul. Trade was intense with Gaul, according to Pliny, because the inhabitants tended to drink Italian wine unmixed and without restraint.[9] Although unpalatable to adults, it was customary, at the time, for young people to drink wine mixed with a good proportion of water.

As the laws on provincial viticulture were relaxed, vast vineyards began to flourish in the rest of Europe, especially Gaul (present-day France) and Hispania. This coincided with the cultivation of new vines, such as biturica, an ancestor of the Cabernets. These vineyards became so successful that Italy ultimately became an import centre for provincial wines.[3]

Depending on the vintage, modern Italy is the world's largest or second-largest wine producer. In 2005, production was about 20% of the global total, second only to France, which produced 26%. In the same year, Italy's share in dollar value of table wine imports into the U.S. was 32%, Australia's was 24%, and France's was 20%. Along with Australia, Italy's market share has rapidly increased in recent years.[10]

Italian appellation system

In 1963, the first official Italian system of classification of wines was launched. Since then, several modifications and additions to the legislation have been made, including a major modification in 1992. The last modification, which occurred in 2010, established four basic categories which are consistent with the latest European Union wine regulations (2008–09). The categories, from the bottom to the top level, are:

- Vini (wines - informally called 'generic wines'): wines can be produced anywhere in the territory of the EU, the label includes no indication of geographical origin of the grape varieties used or the vintage. (The label only reports the colour of the wine.)

- Vini varietali (varietal wines): generic wines that are made either mostly (at least 85%) from one kind of authorized 'international' grape variety (Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc, Syrah) or entirely from two or more of them, grape variety or varieties and vintage may be indicated on the label. (The prohibition to indicate the geographical origin is instead maintained. These wines can be produced anywhere in the territory of the EU.)

- Vini IGP (wines with Protected Geographical Indication also traditionally implemented in Italy as IGT - Typical Geographical Indication): wines produced in a specific territory within Italy and following a series of specific and precise regulations on authorized varieties, viticultural and vinification practices, organoleptic and chemico-physical characteristics, labeling instructions, etc. Currently (2016) there exist 118 IGPs/IGTs.

- Vini DOP (wines with Protected Designation of Origin): this category includes two sub-categories: Vini DOC (Controlled Designation of Origin) and Vini DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Designation of Origin). DOC wines must have been IGP wines for at least 5 years. They generally come from smaller regions within a certain IGP territory that are particularly vocated for their climatic and geological characteristics, quality, and originality of local winemaking traditions. They also must follow stricter production regulations than IGP wines. A DOC wine can be promoted to DOCG if it has been a DOC for at least 10 years. In addition to fulfilling the requisites for DOC wines, DOCG wines must pass stricter analyses prior to commercialization, including a tasting by a specifically appointed committee. DOCG wines must also demonstrate superior commercial success. Currently (2016) there exist 332 DOCs and 73 DOCGs for a total of 405 DOPs.

A number of sub-categories exist pertaining to the regulation of sparkling wine production (e.g. Vino Spumante, Vino Spumante di Qualità, Vino Spumante di Qualità di Tipo Aromatico, Vino Frizzante).

Within the DOP category, 'Classico' is a wine produced in the original historic centre of the protected territory. 'Superiore' is a wine with at least 0.5 more alc%/vol than its corresponding regular DOP wine and produced using a smaller allowed quantity of grapes per hectare, generally yielding a higher quality. 'Riserva' is a wine that has been aged for a minimum period of time. The length of time varies with (red, white, Traditional-method sparkling, Charmat-method sparkling). Sometimes, 'Classico' or 'Superiore' are themselves part of the name of the DOP (e.g. Chianti Classico DOCG or Soave Superiore DOCG).

The Italian Ministry of Agriculture (MIPAAF) regularly publishes updates to the official classification.[11][12]

Looser regulations do not necessarily correspond to lower quality. In fact, many IGP wines are actually high-quality wines. Talented winemakers sometimes wish to create wines using varietals or varietal percentages that do not match DOC or DOCG requirements. "Super Tuscans", for example, are generally high-quality wines that carry the IGP designation. There are several other IGP wines of superior quality, as well.

Unlike France, Italy has never had an official classification of its best 'crus'. Private initiatives like the Comitato Grandi Cru d'Italia (Committee of the Grand Crus of Italy) and the Instituto del Vino Italiano di Qualità—Grandi marchi (Institute of Quality Italian Wine—Great Brands) each gather a selection of renowned top Italian wine producers, in an attempt to unofficially represent the Italian wine excellence.

In 2007 the Barbaresco Consorzio was the first to introduce the Menzioni Geografiche Aggiuntive (additional geographic mentions) also known as MEGA or subzones. Sixty-five subzone vineyard areas were identified in 2007 and one additional subzone was approved in 2010, bringing the final number to 66.[13] The main goal was to put official boundaries to some of the most storied crus in order to protect them from unjustified expansion and exploitation.[13]

The Barolo Consorzio followed suit in 2010 with 181 MEGA, of which 170 were vineyard areas and 11 were village designations.[13] Following the introductions of MEGA for Barbaresco and Barolo the term Vigna (Italian for vineyard) can be used on labels after its respective MEGA and only if the vineyard is within one of the approved official geographic mentions.[13] The official introduction of subzones is strongly advocated by some for different denominations, but so far Barolo and Barbaresco are the only ones to have them.[14]

Geographical characteristics

Important wine-relevant geographic characteristics of Italy include:

- The extensive latitudinal range of the country permits wine growing from the Alps in the north to almost-within-sight of Africa in the south.

- The fact that Italy is a peninsula with a long shoreline contributes to moderating climate effects to coastal wine regions.

- Italy's mountainous and hilly terrain provides a variety of altitudes and climate and soil conditions for grape growing.

Italian wine regions

Italy's twenty wine regions correspond to the twenty administrative regions of the country. Understanding the differences between these regions is very helpful in understanding the different types of Italian wine. Wine in Italy tends to reflect the local cuisine. Regional cuisine also influences wine. The DOCG wines are located in 15 different regions but most of them are concentrated in Piedmont, Lombardia, Veneto and Tuscany. Among these are appellations appreciated and sought after by wine lovers around the world: Barolo, Barbaresco, and Brunello di Montalcino (colloquially known as the "Killer Bs"). Other notable wines that have gained attention in recent years in the international markets and among specialists are: Amarone della Valpolicella, Prosecco di Conegliano- Valdobbiadene, Taurasi from Campania, Franciacorta sparkling wines from Lombardy; evergreen wines are Chianti and Soave, while new wines from the Centre and South of Italy are quickly gaining recognition: Verdicchio, Sagrantino, Primitivo, Nero D'Avola among others. The Friuli-Venezia Giulia is world-famous for the quality of her white wines, like Pinot Grigio. Special sweet wines like Passitos and Moscatos, made in different regions, are also famous since old time.

Sannio

- Falanghina del Sannio

- Camaiola (Barbera del Sannio)

- Aglianico del Sannio

Grapes

- Nebbiolo

- Barbera

- Dolcetto

- Freisa

- Arneis

- Chardonnay

Vini rossi

- Barolo

- Barbaresco

- Barbera

- Grignolino

Grapes

- Chardonnay

- Pinot Noir

- Pinot Bianco

Vini spumanti

- Berlucchi

- Ca’ del Bosco

- Bellavista

Vini rossi

- Nebbiolo o Chiavennasca

Vini bianchi

Vini rossi

- Amarone

- Recioto della Valpolicella

- Bardolino

The main grape varieties for the production of Valpolicella (Amarone, Recioto, Ripasso and Classico) and Bardolino (Superiore and Classico) are the same: Corvina, Rondinella and Molinara. They are all native red varieties of the province of Verona. The most important is Corvina. The Corvina berry flesh has a sweet flavour profile and its skin has a blue-violet colour with a cherry note. Corvina and the other varieties are vinified in different ways to obtain different wines. To obtain Recioto and Amarone, first, drying is carried out. For Valpolicella and Bardolino the vinification takes place immediately after the harvest. The Adige river divides the two production areas on the right Adige towards Lake Garda Bardolino is produced on the left Valpolicella. Many wineries produce both wines. With a particular vinification, Chiaretto (rosé) and Bardolino novello are also obtained, always starting from the same varieties.

Vini bianchi

- Custoza

- Recioto di Soave

- Soave

- Garda

- Pinot Grigio delle Venezie

Vini spumanti

- Prosecco

- Durello

Grapes

- Gewurtztraminer

- Schiava

- Legrein

- Muller-Turgau

Vini rossi

- Moscato Rosa

Vini bianchi

- Gewurtztraminer

Vini bianchi

- Friulano

Grapes

Vini rossi

- Chianti

- Brunello di Montalcino

- Morellino di Scansano

Vini bianchi

Vini bianchi

- Torgiano

- Sagrantino di Montefalco

Grapes

Vini rossi

Vini bianchi

Vini rossi

- Taurasi

- Falanghina

Vini bianchi

Vini rossi

- Primitivo

- Negramaro

- Salice Salentino

- Susumaniello

- Ottavianello

- Nero di Troia

Vini bianchi

- Bianco D’alessano

- Bombino Bianco.

Vini rossi

- Nero d'Avola

Vini bianchi

- Marsala

- Malvasia

Italian grape varieties

Italy's Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MIPAAF), has documented over 350 grapes and granted them "authorized" status. There are more than 500 other documented varieties in circulation as well. The following is a list of the most common and important of Italy's many grape varieties.

Bianco (White)

- Arneis: A variety from Piedmont, which has been grown there since the 15th century.

- Catarratto: Common in Sicily and the most widely planted white variety in Salaparuta.

- Fiano: Grown on the southwest coast of Italy.

- Friulano: A variety also known as Sauvignon Vert or Sauvignonasse, it yields one of the most typical wines of Friuli. The wine was previously known as Tocai but the old name was prohibited by the European Court of Justice to avoid confusion with the Tokay dessert wine from Hungary.

- Garganega: The main grape variety for wines labelled Soave and Custoza, this is a dry white wine from the Veneto wine region of Italy. It is popular in northeast Italy around the city of Verona. Currently, there are over 3,500 distinct producers of Soave.

- Greco di Tufo: Grown on the southwest coast of Italy.

- Malvasia bianca: A white variety that occurs throughout Italy. It has many clones and mutations.

- Moscato blanc: Grown mainly in Piedmont, it is mainly used in the slightly-sparkling (frizzante), semi-sweet Moscato d'Asti. Not to be confused with Moscato Giallo and Moscato rosa, two Germanic varietals that are grown in Trentino Alto-Adige.

- Nuragus: An ancient Sardinian variety found in southern Sardegna, producing light and tart wines usually consumed as aperitifs.

- Passerina: mainly derives from Passerina grapes (it may even be produced purely with these), plus a minimum percentage of other white grapes and may be still, sparkling or passito. The still version has an acidic profile, which is typical of these grapes.

- Pecorino: Native to Marche and Abruzzo, it is used in the Falerio dei Colli Ascolani and Offida DOC wines. It is low-yielding but will ripen early and at high altitudes. Pecorino wines have a rich, aromatic character.

- Pigato: An acidic variety from Liguria that is vinified to pair with seafood.

- Pinot grigio: A successful commercial grape (known as Pinot Gris in France), its wines are characterized by crispness and cleanness. The wine can range from mild to full-bodied.

- Ribolla Gialla: A Greek variety introduced by the Venetians that now makes its home in Friuli.

- Trebbiano: This is the most widely planted white varietal in Italy. It is grown throughout the country, with a special focus on the wines from Abruzzo and from Lazio, including Frascati. Trebbiano from producers such as Valentini have been known to age for 15+ years. It is known as Ugni blanc in France.

- Verdicchio o Trebbiano di Lugana: This is grown in the areas of Castelli di Jesi and Matelica in the Marche region and gives its name to the varietal white wine made from it. The name comes from "verde" (green). In the last few years Verdicchio wines are considered to be the best white wines of Italy.[15]

- Vermentino: This is widely planted in Sardinia and is also found in Tuscan and Ligurian coastal districts. The wines are a popular accompaniment to seafood.

Other important whites include Carricante, Coda de Volpe, Cortese, Falanghina, Grechetto, Grillo, Inzolia, Picolit, Traminer, Verduzzo, and Vernaccia.

Non-native varieties include Chardonnay, Gewürztraminer (sometimes called traminer aromatico), Petite Arvine, Riesling, Sauvignon blanc, and others.

Rosso (red)

- Aglianico: considered to be one of the three greatest Italian varieties with Sangiovese and Nebbiolo, and sometimes called "The Barolo of the South" (il Barolo del Sud) due to its ability to produce fine wines.[16] It is primarily grown in Basilicata and Campania to produce DOCG wines, Aglianico del Vulture Superiore and Taurasi.[17]

- Barbera: The most widely grown red wine grape of the Piedmont and Southern Lombardy regions, the largest plantings of Barbera are found near the towns of Asti, Alba, and Pavia. Barbera wines were once considered simply "what you drank while waiting for the Barolo to be ready", but with a new generation of winemakers, this is no longer the case. The wines are now meticulously vinified. In the Asti region, Barbera grapes are used in making "Barbera d'Asti Superiore", which may be aged in French barriques to become Nizza, a quality wine aimed at the international market. The vine has bright cherry-coloured fruit, and its wine is acidic with a dark colour.

- Corvina: Along with the varieties Rondinella and Molinara, this is the principal grape which makes the famous wines of the Veneto: Valpolicella and Amarone. Valpolicella wine has dark cherry fruit and spice. After the grapes undergo passito (a drying process), the wine is now called Amarone, and is high in alcohol (16% and up) and characterized by raisin, prune, and syrupy fruits. Some Amarones can age for 40+ years and command spectacular prices. In December 2009, there was a celebration when the acclaimed Amarone di Valpolicella was finally awarded its long-sought DOCG status. The same method used for Amarone is used for Recioto, the oldest wine produced in this area, but the difference is that Recioto is a sweet wine.[18]

- Dolcetto: A grape that grows alongside Barbera and Nebbiolo in Piedmont, its name means "little sweet one", referring not to the taste of the wine, but the ease in which it grows and makes good wines suitable for everyday drinking. Flavours of concord grape, wild blackberries, and herbs permeate the wine.

- Malvasia nera: Red Malvasia variety from Piedmont. A sweet and perfumed wine, sometimes pronounced in the passito style.

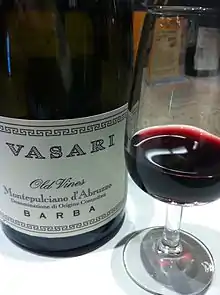

- Montepulciano: Not to be confused with the Tuscan town of Montepulciano, it is the most widely planted grape on the opposite coast in Abruzzo. Its wines develop silky plum-like fruit notes, friendly acidity, and light tannins. More recently, producers have been creating a rich, inky, extracted version of this wine, a sharp contrast to the many inferior bottles produced in the past.[19]

- Nebbiolo: The noblest of Italy's varieties. The name (meaning "little fog") refers to the autumn fog that blankets most of Piedmont where Nebbiolo is chiefly grown, and where it achieves the most successful results. A difficult grape variety to cultivate, it produces the most renowned Barolo and Barbaresco, made in the province of Cuneo, along with the lesser-known Ghemme and Gattinara, made in the provinces of Novara and Vercelli respectively, and Sforzato, Inferno and Sassella made in Valtellina. Traditionally produced Barolo can age for fifty years-plus, and is regarded by many wine enthusiasts as the greatest wine of Italy.[20]

- Negroamaro: The name literally means "black bitter". A widely planted grape with its concentration in the region of Puglia, it is the backbone of the Salice Salentino.

- Nero d'Avola: This once-obscure native varietal wine of Sicily is gaining attention for its dark fruit notes and strong tannins. The quality of Nero d'Avola has surged in recent years.[21]

- Primitivo: A red grape found in southern Italy, most notably in Apulia. Primitivo ripens early and thrives in warm climates, where it can achieve very high alcohol levels. Both Primitivo and California Zinfandel are clones of the Croatian grape Crljenak Kaštelanski.

- Sagrantino: A rare native of Umbria, which although by 2010 planted on only 994 hectares (2,460 acres),[22] the wines produced from it (either as 100% Sagrantino in Montefalco Sagrantino or blended with Sangiovese as Montefalco Rosso) are world-renowned and very high in tannins. These wines can also age for many years.

- Sangiovese: Italy's claim to fame and the pride of Tuscany, it is most notably the predominant grape variety in Chianti and Chianti Classico, and the sole ingredient in Brunello di Montalcino. Sangiovese is also a major constituent of dozens of other denominations such as Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Rosso di Montalcino and Montefalco Rosso, as well as the basis of many of the acclaimed, modern-styled "Super-Tuscans", where it is blended with three of the Bordeaux varietals (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc) and typically aged in French oak barrels, resulting in a wine primed for the international market in the style of a typical California cabernet: oaky, high-alcohol, and a ripe, fruit-forward profile.[23]

Other major red varieties are Cannonau, Ciliegiolo, Gaglioppo, Lagrein, Lambrusco, Monica, Nerello Mascalese, Pignolo, Refosco, Schiava, Schioppettino, Teroldego, and Uva di Troia.

"International" varieties such as Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah are also widely grown.

Super Tuscans

The term "Super Tuscan" (mostly used in the English-speaking world and less known in Italy)[24] describes any wine (mostly red, but sometimes also white) produced in Tuscany that generally does not adhere to the traditional local DOC or DOCG regulations. As a result, Super Tuscans are usually Toscana IGT wines, while others are Bolgheri DOC, a designation of origin rather open to international grape varieties. Traditional Tuscan DOC(G)s require that wines are made from native grapes and mostly Sangiovese. While sometimes Super Tuscans are actually produced by Sangiovese alone, they are also often obtained by (1) blending Sangiovese with international grapes (such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, and Syrah) to produce red wines, (2) blending international grapes alone (especially classic Bordeaux grapes for reds; Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc for whites), or (3) using one single international variety. In a sense, red Super Tuscans anticipated the Meritage, a well-known category of international Bordeaux-style reds of US origin.

Although an extraordinary amount of wines claim to be “the first Super Tuscan,” most would agree that this credit belongs to Sassicaia, the brainchild of marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, who planted Cabernet Sauvignon at his Tenuta San Guido estate in Bolgheri back in 1944. It was for many years the marchese's personal wine, until, starting with the 1968 vintage, it was released commercially in 1971.[25]

In 1968 Azienda Agricola San Felice produced a Super Tuscan called Vigorello, and in the 1970s Piero Antinori, whose family had been making wine for more than 600 years, also decided to make a richer wine by eliminating the white grapes from the Chianti blend, and instead, adding Bordeaux varietals (namely, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot). He was inspired by Sassicaia, of which he was given the sale agency by his uncle Mario Incisa della Rocchetta. The result was one of the first Super Tuscans, which he named Tignanello, after the vineyard where the grapes were grown. What was formerly Chianti Classico Riserva Vigneto Tignanello, was pulled from the DOC in 1971, first eliminating the white grapes (then compulsory in Chianti DOC) and gradually adding French varieties. By 1975, Tignanello was made with 85% Sangiovese, 10% Cabernet Sauvignon, and 5% Cabernet Franc, and it remains so today.[25] Other winemakers started experimenting with Super Tuscan blends of their own shortly thereafter.

Because these wines did not conform to strict DOC(G) classifications, they were initially labelled as vino da tavola, meaning "table wine," an old official category ordinarily reserved for lower quality wines. The creation of the Indicazione Geografica Tipica category (technically indicating a level of quality between vino da tavola and DOC(G)) in 1992 and the DOC Bolgheri label in 1994 helped bring Super Tuscans "back into the fold" from a regulatory standpoint. Since the pioneering work of the Super Tuscans, there has been a rapid expansion in the production of high-quality wines throughout Italy that do not qualify for DOC or DOCG classification, as a result of the efforts of a new generation of Italian wine producers and, in some cases, flying winemakers.

Wine guides

Many international wine guides and wine publications rate the most popular Italian wines. Among the Italian publications, Gambero Rosso is probably the most influential. In particular, the wines that are annually given the highest rating of "three glasses" (Tre Bicchieri) attract much attention. Recently, other guides, such as Slow Wine, published by Slow Food Italia, and Bibenda, compiled by the Fondazione Italiana Sommelier, have also gained attention both among professionals and amateurs. Slow Wine has the interesting feature of reporting on several wineries (small and medium) that genuinely represent the territory and on products that are especially interesting for their price/quality ratio (Vini Slow and Vini Quotidiani).

Vino cotto and vincotto

Vino cotto (literally cooked wine) is a form of wine from the Marche and Abruzzo regions in Central Italy. It is typically made by individuals for their own use as it cannot legally be sold as wine. The must, from any of several local varieties of grapes, is heated in a copper vessel where it is reduced in volume by up to a third before fermenting in old wooden barrels. It can be aged for years, barrels being topped up with each harvest. It is a strong ruby-coloured wine, somewhat similar to Madeira, usually drunk with sweet puddings.

Vincotto, typically from Basilicata and Apulia, also starts as a cooked must but is not fermented, resulting in a sweet syrup suitable for the preparation of sweets and soft drinks. Once reduced and allowed to cool it is aged in storage for a few years.

See also

References

- Karlsson, Per (14 April 2019). "World wine production reaches record level in 2018, consumption is stable". BKWine Magazine. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Dodd, Emlyn (2022-07-01). "The Archaeology of Wine Production in Roman and Pre-Roman Italy". American Journal of Archaeology. 126 (3): 443–480. doi:10.1086/719697. ISSN 0002-9114. S2CID 249679636.

- "Wine". Unrv.com. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p. 757.

- Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p. 66.

- Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84

- Researchers Discover Italy’s Oldest Wine in Sicilian Cave, SmithsonianMag.com, August 31, 2017.

- Dodd, Emlyn (2022-07-01). "The Archaeology of Wine Production in Roman and Pre-Roman Italy". American Journal of Archaeology. 126 (3): 443–480. doi:10.1086/719697. ISSN 0002-9114. S2CID 249679636.

- "Wine and Rome". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Mulligan, Mary Ewing and McCarthy, Ed. Italy: A passion for wine. Indiana Beverage Journal, 2006.

- "Mipaaf - Vini DOP e IGP". Politicheagricole.it. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- "Mipaaf - Disciplinari dei vini DOP e IGP italiani". Politicheagricole.it. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- K. O'Keefe Barolo and Barbaresco: the King and Queen of Italian Wine California University Press 2014 ISBN 9780520273269.

- Speller, Walter (26 March 2013). "Kerin O'Keefe's Montalcino subzones". JancisRobinson.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Novella Talamo (20 November 2014). "Il Verdicchio si conferma nel 2015 il vino bianco più premiato d'Italia dalle Guide e nomina sua ambasciatrice l'olimpionica della scherma Elisa Di Francisca - Luciano Pignataro Wineblog". Lucianopignataro.it. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Levine, Allison (12 November 2015). "Aglianico: The Barolo of the South". Napa Valley Register. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- D'Agata, Ian (2014). "Aglianico". Native Wine Grapes of Italy. University of California Press. pp. 162–167. ISBN 978-0-520-27226-2.

- "Simplicissimus BlogFarm". Archived from the original on 2012-09-26. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- "Edoardo Valentini Montepulciano d'Abruzzo - Italian Wine Merchants (IWM)". Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- "The Wine Doctor". Thewinedoctor.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-10. Retrieved 2017-03-28.(subscription required)

- "Nero d'Avola - Best of Sicily Magazine". Bestofsicily.com. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Anderson, Kym; Aryal, Nanda R. (2013). Which Winegrape Varieties are Grown Where? A Global Empirical Picture. University of Adelaide Press. doi:10.20851/winegrapes. hdl:2440/81592. ISBN 978-1-922064-67-7.

- "California Cabernet Wine". Streetdirectory.com. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Peretti, Angelo (2002). Vini delle regioni d'Italia [Wines from the Regions of Italy] (in Italian). Novara: Cartografia di Novara. p. 145. ISBN 88-509-0204-2.

- O'Keefe, Kerin (2009). "Rebels without a cause? The demise of Super-Tuscans" (PDF). The World of Fine Wine (23): 94–99.

Further reading

- Emlyn Dodd, 'The Archaeology of Wine Production in Roman and pre-Roman Italy.' American Journal of Archaeology 126.3: 443–480. https://doi.org/10.1086/719697

- La Sicilia del Vino, di S. Barresi, E. Iachello, E. Magnano di San Lio, A. Gabbrielli, S. Foti, P. Sessa. Fotografia Giò Martorana, Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania 2003

- Kerin O'Keefe, Brunello di Montalcino. Understanding and Appreciating One of Italy's Greatest Wines, University of California Press, 2012. ISBN 9780520265646

- Kerin O'Keefe, Barolo and Barbaresco. The King and Queen of Italian Wine, University of California Press, 2014. ISBN 9780520273269

External links

- Italian Wine Appellations, from the Italian Ministry of Agriculture (IT)

- National Registry of Grape Varieties, from the Italian Ministry of Agriculture (IT)