Ivan Drach

Ivan Fedorovych Drach (Ukrainian: Іва́н Фе́дорович Драч; 17 October 1936 – 19 June 2018) was a Ukrainian poet, screenwriter, literary critic, politician, and political activist.[1][3]

Ivan Fedorovych Drach | |

|---|---|

| Іван Федорович Драч | |

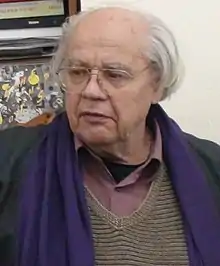

Ivan Drach in 2017 | |

| Born | 17 October 1936 |

| Died | 19 June 2018 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Alma mater | Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv |

| Occupation(s) | Poet Screenwriter Politician Political activist |

| Known for | human rights activism with participation in the Soviet dissident movement and People's Movement of Ukraine |

| Political party | People's Movement of Ukraine |

| Awards | USSR State Prize, Order of the Red Banner of Labour, Hero of Ukraine, Shevchenko National Prize, Antonovych Prize, Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise |

Drach played an important role in the founding of Rukh – the People's Movement of Ukraine – and led the organisation from 1989 to 1992.[1]

Biography

Ivan Drach was born 17 October 1936, in Telizhyntsi, Kyiv Oblast, Ukrainian SSR.[4] After finishing high school, Ivan Drach complied with military service, after which he studied in the Faculty of Language and Literature of Kyiv University from 1959-1963. At this time Drach visited the popular "Klub tvorchoyi molodi" ["Club for Creative Young People" (CCY)] and took part in literary evenings with reading of innovative poems. This creative way started in the period of Khrushchev thaw. Drach made his debut in 1961 with the publication of his poem-tragedy Knife in the Sun in the Kyiv literary newspaper. He worked in the newspapers "Literary Ukraine" and "Fatherland", as well as in the film studio O.P. Dovzhenko, for which he wrote the film A Spring for the Thirsty; filmed in 1965, the film was not released until 1987 after it was censored by the Soviet government.[5] In 1976, he won the USSR State Prize for his work, The Root and the Crown. In the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, Drach was involved in a growing movement of Ukrainian dissident intellectuals that demanded larger cultural autonomy for Ukraine and an honest conversation in the Soviet Union about the stalinist government's actions in Ukraine, particularly the Holodomor.[6]

After the beginning of Perestroika, he resumed contacts with dissident circles. Together with Vyacheslav Chornovil, Mykhailo Horyn, and a number of other Ukrainian activists, in 1989 he created Rukh or People's Movement of Ukraine, first official Ukrainian pro-reform organization. Ivan Drach was the first chairman of Rukh from September 8, 1989 to February 28, 1992. He was co-chairman of the NRU with Chornovil and Horyn from February 28 to December 4, 1992. In the spring of 1990, Ivan Drach was elected to the Verkhovna Rada from Artemivsk (№ 259) constituency by the 66.38% of voters. After retiring from his office in the NRU in late 1992, Ivan Drach retired from politics in 1994. He promoted the use of the Ukrainian language and whilst serving as Ukraine's minister of communication, he proposed wide-ranging measures, including setting quotas for Ukrainian-language broadcasts and tax breaks for Ukrainian publishing.[3]

At the 29 March 1998 elections to the Verkhovna Rada member Drach (NRU party) ran for parliament from Ternopil (№ 167) constituency and voting results (21.04% of the vote), the second time he was elected to Parliament. In the parliamentary elections of March 2002, Drach appeared in the Our Ukraine party at number 31. Thus, the third time he became a deputy. After a long dispute with the party leadership NRU, Drach in March 2005 left the party and joined the Ukrainian People's Party Yuri Kostenko. In the parliamentary elections of March 26, 2006, he was number 14 on the electoral list "Ukrainian National Bloc of Kostenko and the Ivy". But the bloc lost the election and Drach was not elected to Parliament.

From August 1992 to May 19, 2000, he headed the Ukrainian World Coordinating Council. Other positions included the chairmanship of the Ukrainian Intelligentsia Congress and heading the Writers' Union.[7][8] In 2006, he was awarded the title Hero of Ukraine.[9]

Ivan Drach died 19 June 2018 in Feofania Hospital, Kyiv, following an undisclosed illness.[2] Drach requested to be buried next to the grave of his son Maksym in his native Telizhyntsi.[2]

Art

He began his creative path during the “Khrushchev thaw”. He made his debut in 1961, when the Kyiv Literary Gazette published his poem-tragedy Knife in the Sun. During the Soviet era, he wrote entire cycles of poems dedicated to Lenin and the Communist Party to which he belonged. His works were known in the USSR and abroad. His poetry has been translated into Russian (several separate editions), Belarusian, Azerbaijani, Latvian, Moldavian, Polish, Czech, German and other languages.[10]

Awards

- Antonovych prize (1991)

- USSR State Prize (1976)

Poetry collections

- Soniashnyk' (The Sunflower, 1962)

- Protuberantsi sertsia' (Protuberances of the Heart, 1965)

- Poeziï (Poems, 1967)

- Balady budniv (Everyday Ballads, 1967)

- Do dzherel (To the Sources, 1972)

- Korin' i krona (The Root and the Crown, 1974)

- Kyïvs'ke nebo (The Kyivan Sky, 1976)

- Duma pro vchytelia (Duma about the Teacher, 1977)

- Soniashnyi feniks (The Solar Phoenix, 1978)

- Sontse i slovo (The Sun and the Word, 1979)

- Amerykans'kyi zoshyt (American Notebook, 1980)

- Shablia i khustyna (The Saber and the Kerchief, 1981)

- Dramatychni poemy (Dramatic Poems, 1982)

- Kyïvs'kyi oberih (A Kyivan Amulet, 1983)

- Telizhentsi (1985), Khram sontsia (A Temple of the Sun, 1988)

- Lyst do kalyny (A Letter to a Viburnum Tree, 1990)

- Vohon' iz popelu (Fire from the Ashes, 1995)[1]

Movies screenwriting

References

- "Drach, Ivan". encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- "Помер Іван Драч" (in Ukrainian). Мистецький портал «Жінка-УКРАЇНКА». 2018-06-19.

Ivan Drach, prominent Ukrainian poet, dies at 81, UNIAN (19 June 2018) - "Kiev or Kyiv: language an issue in Ukraine - CSMonitor.com". Christian Science Monitor. csmonitor.com. 28 June 2000. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- "Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach dies at 81". Ukrinform. 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "КРИНИЦЯ ДЛЯ СПРАГЛИХ". National Oleksandr Dovzhenko Film Centre (in Ukrainian). June 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Jilge, Winfried (2004). "Holodomor und Nation: Der Hunger im ukrainischen Geschichtsbild". Osteuropa (in German). 54 (12): 146–163. JSTOR 44932109 – via JSTOR.

- "Russian President could at least bow his head respectfully? : UNIAN news". unian.net. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- Wilson, A. (1997). Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780521574570. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- "Про присвоєння І. Драчу звання Герой України – від 19.08.2006 № 705/2006". zakon.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- "freelib.in.ua". freelib.in.ua. Retrieved 2022-02-03.