Ijaw people

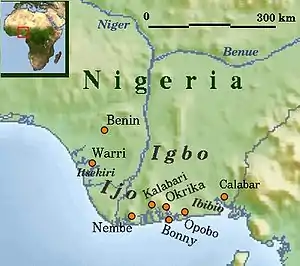

The Ijaw people, otherwise known as the Ijo people,[2] are an ethnic group found in the Niger Delta in Nigeria, with significant population clusters[3] in Bayelsa, Delta, and Rivers.[4] They also occupy Edo,[5] and parts of Akwa Ibom.[6]

Ijo | |

|---|---|

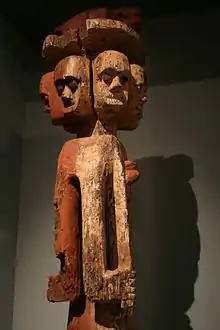

Ijaw statue depicting "the many faces of your enemies" | |

| Total population | |

| 4 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Niger Delta | |

| Languages | |

| Ijaw languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity 65% Islam 1% Traditional 34% | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ekpeye, Oron, Ogoni, Isoko, Eleme. |

Many are found as migrant fishermen in camps as far west as Sierra Leone and as far east as Gabon. They account for about 1.8% of the Nigerian population according to CIA Factbook.[1][7][8][9][10] The Ijaws are unarguably the most populous tribe inhabiting the Niger Delta region and arguably the fourth largest[11] ethnic group in Nigeria.

They have long lived in locations near many sea trade routes, and they were well connected to other areas by trade as early as the late 14th and early 15th centuries.[12][13] In their languages, they often refer to themselves using the endonym Izon.[14]

An ancient ethnic group

History

The Izon People have lived in the Niger Delta region since before the fifth millennium BCE, and they were able to keep a separate identity because they lived where the agriculturally dependent Benue-Kwa groups were unable to penetrate. Some of the earliest archeological findings of Ijaw tribes have been dated to as far back as the early 800s BCE.[15] The timeline that the archaeological excavations provide offers about 3,000 years of evidence of Ijaw history and presence in the Niger Delta.

There has been much argument about which tribe in Nigeria is the oldest. The Ijaws started inhabiting the Niger Delta region of what is now Nigeria as far back as 800 BCE,[16] thus making them one of the world's most ancient peoples.[16][17] They have existed as a distinct language and ethnic group for over 5000 years.[18]

Agadagba-bou, the first ancient Ijaw city-state, existed for more than 400 years,[16] lasting until 1050 CE. Due to internal conflict and violent weather patterns, this city-state was abandoned. Some of the descendants of this city-state created another in the 11th century called Isoma-bou, which lasted until the 16th century. This city-state, like the last, was founded in the Central Delta Wilberforce Island region. The Wilberforce Island region remains the most Ijaw-populated area of Nigeria.

The Ijaws are believed by some to be the descendants of an autochthonous people or an ancient tribe of Africa known as the Oru; the Ijaws were originally known by this name (Oru).[11] These were believed to be the aboriginal people of West Africa and the region of Niger/Benue.

The word ‘Oru’ can be traced to the Egyptian sky god ‘Horus’. Myth explains that the early ancestors of the Ijaw people descended from the sky. The traditional Ijo narratives refer to the ancestors (the Oru-Otu) or the ancient people (Tobu Otu) who descended from the sky (and this were of divine origin). They are also referred to as the water people (Beni-Otu). Although this was a very long time ago, the Ijaws have, however, kept the ancient language and culture of the Orus.

Language and cultural studies have suggested that they are related to the founders of the Great Nile Valley civilization complex (and possibly the lake Chad complex). They immigrated to West Africa from the Nile Valley during antiquity.[11]

The earliest settlement of the Ijaws can be traced to the Nupe region, after a series of migrations from Sudan and Egypt. The migration took place and they moved to the Benin region after settling in Ile-Ife. The early Ijaw people believed in consanguinity — the act of being descended from the same ancestor, and as a result they all saw themselves as one.[19]

Development

The Ijo people have about 51 different clans, and were trading amongst themselves before the arrival of Europeans. Their settlements in the Bini region, lower Niger and the Niger Delta were aboriginal (i.e. being the first). They are known to be exceptional sea people.[20]

In the 12th century, the number of Ijaw states grew, and by the 16th century, the Ijaws formed a number of powerful kingdoms with strong central rule. The Ijaw economy was predominantly supported by fishing, and each clustered group claimed a specific culture and autonomy from the others.

They were among the first people in Nigeria to come in contact with Europeans, the earliest explorers arriving in the early 15th century. After contact with European merchants around 1500 CE, communities began trading in enslaved people[21] as middlemen[22] while they also traded in palm oil. Traders who amassed wealth within this business market found themselves parading power over the government. Each trader purchased as many enslaved people as possible, valuing ability over genetic kinship as most enslaved people's families were split apart and not valued for their rich culture and heritage. Because an able enslaved person could inherit the business of a trader with no heir, it was possible to have (non-Ijaw) leaders who had been born into slavery; such a leader was King Jaja of Opobo.

The Ijaw People bought slaves[22] from Igboland, including Jubo Jubogha, an Igbo man, who was bought by the Ijo people of Bonny. He later earned his way out of slavery and was renamed Jaja.

Over time it was practice for Ijaw villages to buy slaves from Igboland for various reasons, ranging from giving slaves as gifts to newly wed couples and mainly to showcase the wealth of the individual. As was the Ijaw custom, a slave always earned their way out of slavery after serving their master for a number of years. Some Ijaw men went on to marry some slaves, taking them out of slavery by marriage. A number of Ijaw clans thus have remote Igbo ancestry.

The Nembe Ijo people were the first Ijaws to fight and win a battle against the Europeans. Though a short lived victory, a huge precedent was set by way of this.

King Frederick William Koko (Mingi VIII) of the Nembe-Brass Kingdom (1853–1898) led a successful attack on the British Royal Niger Company trading post in 1895.[23] King Koko also took over 43 British hostages,[24] whom he killed and ceremoniously ate. King Koko was offered a settlement for his grievances, but he found the terms unacceptable. After some reprisal attacks by the British, his capital was ransacked. King Koko fled, and so was deposed by the British. He died in exile in 1898.

Language

The Ijaws speak nine closely related Niger-Congo languages, all of which belong to the Ijoid branch of the Niger-Congo tree.[25] The primary division between the Ijo languages is that between Eastern Ijo and Western Ijo, the most important of the former group of languages being Izon, which is spoken by about five million people.

There are two prominent groupings of the Ijaw language. The first, termed either Western or Central Izon (Ijaw) consists of Western Ijaw speakers: Tuomo Clan, Egbema, Ekeremor, Sagbama (Mein), Bassan, Apoi, Arogbo, Boma (Bumo), Kabo (Kabuowei), Ogboin, Tarakiri, and Kolokuma-Opokuma.[26] Nembe, Ogbia, Brass and Akassa (Akaha) dialects represent Southeast Ijo (Izon).[27] Buseni and Okordia dialects are considered Inland Ijo.[28]

It was discovered in the 1980s that a now extinct Berbice Creole Dutch, spoken in Guyana, is partly based on Ijo lexicon and grammar. Its nearest relative seems to be Eastern Ijo, most likely Kalabari.[29][30][31]

Clans

The Ijaw People can be grouped into three.

The first, which is termed as Central Ijaw (Ijo), consists of Central Ijaw languages and subgroups:

Ogbia subgroup and language, Epie-Atisa (Epie) subgroup and language, all part of Ijo people in Bayelsa.

Ijaw Language, spoken by people in Ekeremor, Sagbama (Mein), Amassoma, Apoi, Arogbo, Boma (Bumo), Kabo (Kabuowei),Olodiama, Ogboin, Tarakiri, and Kolokuma-Opokuma, Tungbo, Tuomo, etc. all in Bayelsa.

Nembe Language, spoken by people in Nembe, Brass, and Akassa (Akaha) in Bayelsa.

Abua language, spoken by Abua/Odual people in Rivers State. Other Central subgroups are Biseni People, Akinima, Mbiama, Engeni and some subgroups in the Ahoda regions in Rivers State.

The second is the Eastern Ijaw (Ijo) found in Rivers[32] and Akwa Ibom States.

They include Kalabari (Abonnema, Buguma, Degema etc.), Okirika, Opobo, Port Harcourt South, Bonny, Finima, Nkoro, Andoni, and Obolo people (part of Andoni) [33]), who can also be traced to Akwa Ibom State, near the border with Rivers State.

Third is the Western Ijaw (Ijo), found in Delta, Ondo and Edo states.

They can be found in Ondo state[34] due to migrations many years prior. The Arogbo Ijaws and the Western Apoi tribe of the Ijaw people live in Ondo State, Nigeria. The tribe (also called Ijaw Apoi or Apoi) consists of nine settlements: Igbobini, Ojuala, Ikpoke, Inikorogha, Oboro, Shabomi, Igbotu, Kiribo and Gbekebo.

The Apoi inhabited higher ground than most of the other Ijaw tribes. They speak the Yoruba language and Ijaw. They are bordered to the north by the Ikale and to the west by the Ilaje.[35] The clan also shares border with the Arogbo Ijaw[36] to the south of Ondo and the Furupagha Ijaw to the east across the Siloko River.

The founding ancestors of the Arogbo were part of the same migration from Ujo-Gbaraun town. After a brief stop at Oproza, led by Eji and his younger brother, Perebiyenmo and sister, Fiyepatei, they went on to Ukparomo (now occupied by the towns of Akpata, Opuba, Ajapa, and Ukpe). They stayed here for some time, about the length of the reign of two Agadagbas (military priest-rulers of the shrine of Egbesu). They then moved to the present site of Arogbo. From this place descendants spread out to found the Arogbo Ibe. It was from Arogbo that some ancestors migrated northwards up the old course of the Forcados river and settled near the site of Patani.

The Isaba, Kabo, Tuomo, Kumbo, Ogulagha, Patani, and Gbaramatu peoples of Delta state are also part of the Western Ijo subgroups.

In Edo state, the Ijo first settled in an area called Ikoro.[37] Their traditional rulers are called Peres and Agadagbas, and are thought to predate the Benin monarchy. 'Pere' means king in some of the Ijaw languages.[38]

| Name | State | Alternate Names |

|---|---|---|

| Abureni | Bayelsa | |

| Akassa | Bayelsa | Akaha, Akasa |

| Andoni | Rivers | |

| Anyama | Bayelsa | |

| Apoi (Eastern) | Bayelsa | |

| Apoi (Western) | Ondo | |

| Arogbo | Ondo | |

| Bassan | Bayelsa | Basan |

| Bille | Rivers | Bile, Bili |

| Bumo | Bayelsa | Boma, Bomo |

| Buseni | Bayelsa | Biseni |

| Egbema | Delta | |

| Operemor | Delta/Bayelsa | Operemor, Ekeremo,Ojobo |

| Ekpetiama | Bayelsa | |

| Gbaramatu | Delta | Gbaramatu |

| Gbaran | Bayelsa | Gbarain |

| Ibani | Rivers | |

| Iduwini | Bayelsa/Delta | |

| Isaba | Delta | |

| Kabo | Delta | Kabowei, Kabou |

| Kalabari | Rivers | |

| Ke | Rivers | Obiansoama, Kenan City |

| Kolo Creek | Bayelsa | |

| Kolokuma | Bayelsa | |

| Kou | Bayelsa | |

| Kula | Rivers | |

| Kumbo | Delta | Kumbowei |

| Mein | Delta/Bayelsa | |

| Nkoro | Rivers | Kirika, Nk City |

| Obotebe | Delta | |

| Odimodi | Delta | |

| Ogbe | Delta | Ogbe-Ijoh |

| Ogboin | Bayelsa | |

| Ogulagha | Delta | Ogula,Small London |

| Okrika | Rivers | Wakirike |

| Okordia | Bayelsa | Okodia, Akita |

| Olodiama (East) | Bayelsa | |

| Oloibiri | Bayelsa | |

| Opokuma | Bayelsa | |

| Oporoma | Bayelsa | Oporomo |

| Oruma | Bayelsa | Tugbene |

| Oyakiri | Bayelsa | Beni |

| Seimbiri | Delta | |

| Tarakiri (East) | Bayelsa | |

| Tarakiri (West) | Delta | |

| Tungbo | Bayelsa | |

| Tuomo | Delta / Bayelsa |

T.T Clan |

| Zarama | Bayelsa | |

| Unyeada | Rivers | Unyeada |

Traditional occupations

The Ijaws were one of the first of Nigeria's peoples to have contact with Westerners, and were active as go-betweens in the trade between visiting Europeans and the peoples of the interior, particularly in the era before the discovery of quinine, when West Africa was still known as the "White Man's Graveyard" because of the endemic presence of malaria. Some of the kin-based trading lineages that arose among the Ijaws developed into substantial corporations which were known as "houses"; each house had an elected leader as well as a fleet of war canoes for use in protecting trade and fighting rivals. The other main occupation common among the Ijaws has traditionally been fishing and farming.[40][41]

Being a maritime people, many Ijaws were employed in the merchant shipping sector in the early and mid-20th century (pre-Nigerian Independence). With the advent of oil and gas exploration in their territory, some are now employed in that sector. Another major occupation is service in the civil service sector of the Nigerian states of Bayelsa and Rivers, where they are predominant.[42]

Extensive state-government sponsored overseas scholarship programs in the 1970s and 1980s have also led to a significant presence of Ijaw professionals in Europe and North America (the so-called Ijaw diaspora). Another contributing factor to this human capital flight is the abject poverty in their homeland of the Niger Delta, resulting from decades of neglect by the Nigerian government and oil companies in spite of continuous petroleum prospecting in this region since the 1950s.[43]

Lifestyle

The Ijaw people live by fishing supplemented by farming paddy-rice, plantains, Cassava, yams, cocoyams, bananas and other vegetables as well as tropical fruits such as guava, mangoes and pineapples; and trading. Smoke-dried fish, timber, palm oil and palm kernels are processed for export. While some clans (those to the east- Akassa, Bille, Kalabari, Nkoro, Okrika, Andoni and Bonny) had powerful kings and a stratified society, other clans are believed not to have had any centralized confederacies until the arrival of the British. However, owing to the influence of the neighbouring Kingdom of Benin, individual communities even in the western Niger Delta also had chiefs and governments at the village level.[44]

For women, there are traditional rights of passage throughout life, marked with iria ceremonies.[45]

Funeral ceremonies, particularly for those who have accumulated wealth and respect, are often very dramatic. Traditional religious practices center around "Water spirits" in the Niger river, and around tribute to ancestors.[46]

Marriages

Marriages are completed by the payment of a bridal dowry, which increases in size if the bride is from another village (so as to make up for that village's loss of her children). Unlike most tribes, the Ijaws have two forms of marriage.

In the first, which is a small-dowry marriage, the groom is traditionally obliged to offer a payment to the wife's family, which is typically cash. The dowry sum is not paid completely. At the death of the bride's father, the groom then pays the complete dowry balance as part of his contribution to his father-in-law's burial. In this type of marriage, the children trace their line of inheritance through their mother to her family, meaning that when the children grow up, they have more choices as to where they can live. They can either decide to live with their father's people or with their mother's. They are considered to be from both their father's and mother's places. This is the most common type of marriage.

In contrast to the first type, the second type of marriage is a large-dowry marriage. Here, the children belong to the father's family as a result of the fact that the dowry is greater in size.

Religion and cultural practices

Although the Ijaw are now primarily Christians (65% profess to be),[47] with Roman Catholicism, Zion Church, Anglicanism and Pentecostalism being the varieties of Christianity most prevalent among them, they also have elaborate traditional religious practices of their own.

Traditionally, the Ijaws hold celebrations to honour the spirits that last for several days. The highlight of these festivals is the role of masquerades.

Veneration of ancestors plays a central role in Ijaw traditional religion, while water spirits, known as Owuamapu, also figure prominently in the Ijaw pantheon. In addition, the Ijaw practice a form of divination called Igbadai, which involves recently deceased individuals being interrogated on the causes of their death.

Ijaw religious beliefs hold that the owuamapu are like humans in having personal strengths and shortcomings, and that humans dwell among these water spirits before being born. The role of prayer in the traditional Ijaw system of belief is to maintain the living in the good graces of the owuamapu, among whom they dwelt before being born into this world, and each year the Ijaw hold celebrations to honour the spirits lasting for several days.

Central to the festivities is the role of masquerades, in which men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing. Particularly spectacular masqueraders are taken to actually be in the possession of the particular spirits on whose behalf they are dancing.[48] Important deities in the Ijaw religion include Egbesu, whose totems are the leopard, panther and lion, and who manifests as a god of justice.[49] Many of the Ijaws are warriors, and often offer veneration to Egbesu as a god of war as well. At the sound of the 'Asawana', the Ijaw warrior readies himself for war using Egbesu as a shield.

One of Egbesu's prime laws is that an Ijaw person should not be the cause of the problem, or the one to start the fight, but should respond only when he or she must. This is a manifestation of the Ijaw virtue of patience.

There are also a small number of converts to Islam, the most notable being the founder of the Delta People Volunteer Force Mujahid Dokubo-Asari.

Notable leaders

Food customs

Like many ethnic groups in Nigeria, the Ijaws have many local foods that are not widespread in Nigeria. Many of these foods involve fish and other seafoods such as clams, oysters and periwinkles; yams and plantains. Some of these foods are:[51]

- Polofiyai — A very rich soup made with yams and palm oil.

- Kekefiyai— A pottage made with chopped unripened (green) plantains, fish, other seafood or game meat ("bushmeat") and palm oil.

- Fried or roasted fish and plantain — Fish fried in palm oil and served with fried plantains.

- Gbe — The grub of the raffia-palm tree beetle that is eaten raw, dried, fried in groundnut oil or pickled in palm oil.

- Kalabari "sea-harvest" fulo— A rich mixed seafood soup or stew that is eaten with foofoo, rice or yams.

- Owafiya (bean pottage) — A pottage made with Beans, palm oil, fish or bushmeat, Yam or Plantain. It is taken with processed Cassava or Starch.

- Geisha soup — This a kind of soup cooked from the geisha fish; it is made with pepper, salt, water and boiling it for some minutes.

- Opuru-fulou — Also referred to as prawn soup, prepared mainly with prawn, Ogbono (Irvingia gabonensis seeds), dried fish, table salt, crayfish, onions, fresh pepper, and red palm oil.

- Yellow soup - Made with fresh fish (mostly catfish) and fresh pepper and red palm oil and thickened with garri or biscuits. Sometimes fresh tomatoes can be added to the soup.

- Onunu - Made with pounded yams and boiled overripe plantains. It is mostly enjoyed by the Okrikans[52]

- Kiri-igina — Prepared without cooking on fire with Ogbono (Irvingia gabonensis seeds), dried fish, table salt, crayfish.[52][53]

- Ignabeni — A watery soup prepared with either yam or plantain seasoned with teabush leaves, pepper, goat meat, and fish.[53]

- Pilo-garri — A Bille meal mostly eaten during the raining season. It is prepared with dry garri, red palm oil, salt and eaten with roasted seafoods (fish, Isemi, Ngbe, Ikoli, etc.).

- Igbugbai fiyai - A soup prepared without oil, only fish, onion, periwinkle, Bush leaves and other seafood. This soup, once prepared, is mostly eaten by Odimodi people.

- Kpanfaranran [fry fiyai] A soup prepared by frying the palm oil before adding your fish, meat, crayfish, periwinkle, and other seafood. This food is mostly cooked by the Odimodi people.

Ethnic identity

Formerly organized into several loose clusters of villages (confederacies) which cooperated to defend themselves against outsiders, the Ijaw increasingly view themselves as belonging to a single coherent nation, bound together by ties of language and culture.

This tendency has been encouraged in large part by what are considered to be environmental degradations that have accompanied the exploitation of oil in the Niger delta region which the Ijaw call home, as well as by a revenue sharing formula with the Nigerian Federal Government that is viewed by the Ijaw as manifestly unfair. The resulting sense of grievance has led to several high-profile clashes with the Nigerian Federal authorities, including kidnappings and in the course of which many lives have been lost.

The Ijaw people are resilient and proud. Long before the colonial era, the Ijaw people traveled by wooded boats and canoes to Cameroon, Ghana and other West African countries. They traveled up the River Niger from the River Nun.

Ijaw–Itsekiri conflicts

One manifestation of ethnic violence on the part of the Ijaw has been an increase in the number and severity of clashes between Ijaw militants and those of Itsekiri origin, particularly in the town of Warri.[54]

Deadly conflicts had rocked the South-South region, especially in Delta State, where intertribal killings had resulted in death on both sides.[55] [56] In July 2013, local police discovered mutilated corpses of 13 Itsekiris killed by Ijaws, over a dispute on a candidate for a local council chairman. Several Itsekiri villages, including Gbokoda, Udo, Ajamita, Obaghoro and Ayerode-Zion on the Benin river axis, were razed down while several Itsekiris lost their lives.[57]

Oil conflict

The December 1998 All Ijaw Youths Conference crystallized the struggle with the formation of the Ijaw Youth Movement (IYM) and the issuing of the Kaiama Declaration. In it, long-held Ijaw concerns about the loss of control of their homeland and their own lives to the oil companies were joined with a commitment to direct action. In the declaration, and in a letter to the companies, the Ijaws called for oil companies to suspend operations and withdraw from Ijaw territory. The IYM pledged “to struggle peacefully for freedom, self-determination and ecological justice,” and prepared a campaign of celebration, prayer, and direct action 'Operation Climate Change' beginning December 28, 1998.[58]

In December 1998, two warships and 10–15,000 Nigerian troops occupied Bayelsa and Delta states as the Ijaw Youth Movement (IYM) mobilized for Operation Climate Change. Soldiers entering the Bayelsa state capital of Yenagoa announced they had come to attack the youths trying to stop the oil companies. On the morning of December 30, 1998, two thousand young people processed through Yenagoa, dressed in black, singing and dancing. Soldiers opened fire with rifles, machine guns, and tear gas, killing at least three protesters and arresting twenty-five more. After a march demanding the release of those detained was turned back by soldiers, three more protesters were shot dead. The head of Yenagoa rebels - Chief Oweikuro Ibe - was burned alive in his mansion on December 28, 1998. Amongst his family members to flee the premises before the complete destruction was his only son, Desmond Ibe. The military declared a state of emergency throughout Bayelsa state, imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew, and banned meetings. At military roadblocks, local residents were severely beaten or detained. At night, soldiers invaded private homes, terrorizing residents with beatings and women and girls with rape.[59]

On January 4, 1999 about one hundred soldiers from the military base at Chevron’s Escravos facility attacked Opia and Ikiyan, two Ijaw communities in Delta State. Bright Pablogba, the traditional leader of Ikiyan, who came to the river to negotiate with the soldiers, was shot along with a seven-year-old girl and possibly dozens of others. Of the approximately 1,000 people living in the two villages, four people were found dead and sixty-two were still missing months after the attack. The same soldiers set the villages ablaze, destroyed canoes and fishing equipment, killed livestock, and destroyed churches and religious shrines.[60]

Nonetheless, Operation Climate Change continued, and disrupted Nigerian oil supplies through much of 1999 by turning off valves through Ijaw territory. In the context of high conflict between the Ijaw and the Nigerian Federal Government (and its police and army), the military carried out the Odi massacre, killing scores if not hundreds of Ijaws.[61]

Recent actions by Ijaws against the oil industry have included both renewed efforts at nonviolent action and militarized attacks on oil installations but with no human casualties to foreign oil workers despite hostage-takings. These attacks are usually in response to non-fulfilment by oil companies of memoranda of understanding with their host communities.[62]

Notable Ijaw individuals

- Goodluck Jonathan, politician and 14th President of Nigeria[63]

- J.P. Clark, poet and playwright

- Gabriel Okara, poet and novelist

- Owoye Andrew Azazi, a former Nigerian Chief of Defense Staff and National Security Adviser

- Patience Faka Jonathan, Former First Lady Of Nigeria( 2010-2015)

- King Frederick William Koko, (Mingi VIII) King of Nembe-Brass Kingdom (1853–1898), and many more.

- Timi Dakolo, Nigerian singer-songwriter[64]

- Ibinabo Fiberesima, Nigerian Nollywood actress

- Ben Murray-Bruce, Nigerian media mogul and senator

- Ebikabowei Victor Ben, MEND general

- Eruani Azibapu Godbless, businessman and Bayelsa Commissioner for Health

- Patience Torlowei, artist and fashion designer

- Finidi George, Nigerian footballer and coach

- Taribo West, Nigerian former soccer player and pastor

- Samson Siasia, Nigerian footballer and coach

- Inetimi Odon Timaya, Nigerian singer

- Damini Ogulu (Burna Boy), Nigerian singer and Grammy award winner

- Harrysong, a Nigerian singer-songwriter

- Prince Timi Kakandar, a Nigerian Visual Artist, Painter

- Ideye Brown, Nigerian footballer

- King Alrlfred Diete-Spiff, former Military Governor of Rivers State and Amanayabo (King) of Twon-Brass

- King Edward Asimini William Dappa Pepple III, Perekule XI, Amanayabo (King) of Grand Bonny Kingdom

- Tompolo, Nigerian freedom fighter (ex militant) commander[65]

- Jeremiah Omoto Fufeyin, clergyman.

- Tammy Abraham, professional footballer.[66]

- Timmy Abraham, professional footballer.

- Agbani Darego, professional model and beauty queen.

- Gentle Jack, professional Nollywood actor.

- Dakore Egbuson Akande, Nollywood Actress

- Kingsley Otuaro Former Deputy Governor of Delta State

- Timini Egbuson, Nollywood actor

- Henry Seriake Dickson, politician and former governor

- Timipre Sylva, politician and former governor of Bayelsa State, and former Nigerian Minister of State for Petroleum Resources.

- Adokiye Tombomieye, Vice President of NNPC Limited

- Abel Aboh, Data Management Leader Bank of England [50]

Ijaw organisations

- Andoni Forum USA (AFUSA)

- Ijaw Youth Council

- Ijaw National Congress[67]

- Ijaw Nation Forum (INF)

- Ijaw Elders Forum

- Ijaw Youth Congress

- Congress of Niger Delta Youths

- National Union of Izon-Ebe Students

- Tuomo Youth Congress

- Sagbama Youth Movement

- Ekine Sekiapu Ogbo

- Bomadi Decides

- Bayelsa Youths Council

- The Ogbia brotherhood

- Izon Progressive Congress (IPC)

- Ogbinbiri Progressive Movement

- Egbema Youths Progressive Agenda

- Progressive Youth Leadership Foundation(ND-PYLF)

- Ijaw Nation Development Group (Ijaw Peoples Assembly)

- Izon Ladies Association (ILA)

- Indigenous people of Niger Delta IPND

- National Association Of Ogulagha Clan Students (NAOCS)

- National Association of Burutu Local Government Students (NABLOGS) Worldwide

References

- "Africa: Nigeria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "Ijo". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- "population | Definition, Trends, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- "Being Ijaw in the UK: An oddity among fellow Nigerian youth". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- "Our Story". Indigenous People of Biafra USA. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- "Ijaw group rejects remapping of Akwa Ibom, says it's 'ploy to regroup oil communities'". TheCable. 2023-04-27. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 596. ISBN 9780195337709.

- Gedicks, Al (2001). Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations. South End Press. pp. 50. ISBN 9780896086401.

ijaw million.

- Bob, Clifford (2005-06-06). The Marketing of Rebellion: Insurgents, Media, and International Activism. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780521607865.

- Shoup III, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 130. ISBN 9781598843637.

- "Ijaw Culture: A brief walk into the lives of one of the world's most ancient people". Pulse Nigeria. 2022-11-18. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Showcasing The Ijaw Culture and People of Bayelsa from South-South Nigeria - Courtesy The Scout Association of Nigeria | World Scouting". sdgs.scout.org. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- "Ijo People – Ijo Information". Arts & Life in Africa Online. Archived from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2006.

- "Being Ijaw in the U.K: An oddity among fellow Nigerian youth". aljazeera.com. July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- "Ijaw history, culture and facts". study.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Ijaw history, culture and facts". study.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Fakunle, Mike (2022-05-31). "Top 10 Oldest Tribes In Nigeria". Nigerian Infofinder. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "The History of the Ijaw People | Lifestlye | Religion | Naijabiography". Naijabiography Media. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Baruwa, Eniola (2020-02-02). "Into The Interesting Life Of The Ijaw Tribe Of Nigeria". Zamxa Travel Guide. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Myths, Realities of Ijaws in Destiny with Rivers - Daily Trust". dailytrust.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Ijaw history, culture and facts". study.com. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ahyoxsoft.com. "The Ijaw Tribe of Africa". africabusinessradio.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- alagoa, e j alagoae j (2011-01-01), "Koko, Frederick William", Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-1111, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5, retrieved 2023-06-06

- Etekpe, Ambily (2009). African Political Thought & Its Relevance In Contemporary World Order. Harey Publication Coy. p. 166. ISBN 9789784911504.

- "Ijo | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- "Ijoid languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- "A Brief Walk into the Lives of Ijaw People". Pulse Nigeria. 2019-08-05. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- "The Origination of Ijaw Nation". Creekvibes. 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- Smith, Norval S. H.; Robertson, Ian E.; Williamson, Kay (1987). "The Ịjọ Element in Berbice Dutch". Language in Society. 16 (1): 49–89. doi:10.1017/S0047404500012124. JSTOR 4167815. S2CID 146234088.

- Kouwenberg, Silvia (1994). A Grammar of Berbice Dutch Creole. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Kouwenburg, Silvia (2012). "The Ijo‑derived Lexicon of Berbice Dutch Creole: An A‑typical Case of African Lexical Influence". In Bartens, A.; Baker, P. (eds.). Black Through White: African Words and Calques Which Survived Slavery in Creoles and Transplanted European Languages. London: Battlebridge. pp. 135–153.

- OLANIYI, Bisi (2014). "Rivers Ijaw…Unique people, great culture, endless prospects". The Nation.

- Ibaba, Samuel Ibaba (2012). "Ijaws and the Militianisation of Conflict in the Niger Delta: Exploring the Role of Upland Bias in Resource Allocation". Ijaws and the Militianisation of Conflict Research Gate Journal - Excerpts: 3.

- "Akeredolu and the Plight of the Ijaw Community in Ondo - THISDAYLIVE". www.thisdaylive.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Crisis Brews In Ondo State As Ijaw Community Accuses Ilaje Of Murder, Demands Investigation | Sahara Reporters". saharareporters.com. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Nigeria, News Agency of (2023-04-30). "INC lauds Gov Akeredolu for installing 5 Ijaw kings in Ondo". Peoples Gazette. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Ikoro: So close to civilisation, yet far". Tribune Online. 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Ijo | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- Ijaw National Congress (INC) Constitution

- "Rivers Ijaw…Unique people, great culture, endless prospects". The Nation Newspaper. 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- National African Language Resource Center. "IJAW-National African Language Resource Centre". National African Language Resource Center: 2.

- Alex-Hart, Biebele (May 2016). What's Ethnicity got to do with it? The Workplace Lived Experience of Ethnic Minority (IJAW) Women in the Nigerian Civil Service (phd thesis). University of East London. doi:10.15123/pub.5533.

- "Ijaw: Managing the ethnic question in Nigeria's politics". Vanguard News. 2010-11-20. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- "Showcasing The Ijaw Culture and People of Bayelsa from South-South Nigeria - Courtesy The Scout Association of Nigeria | World Scouting". sdgs.scout.org. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- punchng (3 November 2018). "Iria Festival: Excitement in Rivers community as maidens are set to dance half-naked". Punch Newspapers. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "mask for the ijaw water spirit". masksoftheworld.com. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- "The Interesting Life Of The Ijaw Tribe Of Nigeria". zamxahotels.com. February 2, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- "mask for the ijaw water spirit". masksoftheworld.com. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Elias Courson & Michael E. Odijie (2020) Egbesu: An African Just War Philosophy and Practice, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32:4, 493-508, DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2019.1706460

- "British Data Award". www.refinedng.com. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- Atulegwu, David (2020-06-01). "List of Traditional Foods in Nigeria". Nigerian Infopedia. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- Benjamin, Amadi; Dikhioye, Peters; Emmanuel, Agomuo; Peter, Amadi; Grace, Denson (2018). "Nutrient Composition of Some Selected Traditional Foods of Ijaw People of Bayelsa State". Polish Journal of Natural Sciences. 33 (1): 59–74.

- "Nigerian Arts and Culture Directory". Bayesla State Cuisines. Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Nigeria: The conflict between Itsekiri and Ijaw ethnic groups in Warri, Delta region (March 1997-September 1999)". Refworld. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- "Communal Clash Causes Tension In Delta As Ijaw Youths Kill Four Itsekiri". Information Nigeria. 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Brother Against brother: Reigniting Itsekiri, Ijaw Tensions". The Nation Nigeria. 2014-11-23. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Ijaw/Itsekiri Crisis: Police Recover Gory Corpses of Slain Uduaghan Kinsmen". Sahara Reporters. 2013-07-09. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Kaiama Declaration". www.unitedijaw.com. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Nigeria: 4 and 8 October 1998 seizeure of flow stations of Shell Petroleum Development at Forcados by Ijaw youths, reaction of authorities and treatment of suspects involved". Refworld. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- "NIGERIA". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- "INTERVIEW: Odi 1999 Massacre: Why we will never forgive Obasanjo, Alamieyeseigha – Odi Community Chairman". 2019-11-23. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- "Ijaw Coalition Threatens Legal Action Over Marginal Oil Fields Bid Round". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 2020-06-13. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "Goodluck Jonathan | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- "The Art In The Artist TIMI DAKOLO". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 2019-11-24. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- "Who Is Tompolo? Biography and Net Worth of the Billionaire Militant". BuzzNigeria.com. 2018-06-25. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- Athletic, The. "Tammy Bakumo-Abraham - Premier League Attacker - News, Stats, Bio and more". The Athletic. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- "Ijaw National Congress". Ijaw Nation Forum. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

Other sources

- Human Rights Watch, "Delta Crackdown", May 1999

- Ijaw Youth Movement, letter to "All Managing Directors and Chief Executives of transnational oil companies operating in Ijawland", December 18, 1998

- Project Underground, "Visit the World of Chevron: Niger Delta", 1999

- Kari, Ethelbert Emmanuel. 2004. A Reference Grammar of Degema. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Hlaváčová, Anna: "Three Points of View of Masquerades among the Ijo of the Niger River Delta". In: Playful Performers: African Children's Masquerades. Ottenberg, S.; Binkley, D. (eds.)

External links

- Ijaw World Studies

- The Ijaw Language Dictionary Online

- Ethnologue: "Ijaw Linguistic Tree"

- "Ijo People", University of Iowa

- American Museum of Natural History: "The Art of the Kalabari Masquerade"

- "The Warri Crisis: Fueling Violence" – Human Rights Watch report, November 2003

- "Blood Oil" by Sebastian Junger in Vanity Fair, February 2007 (accessed 28/1/2007), deals partly with the Ijaw