Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jin dynasty (/dʒɪn/,[2] [tɕín]; Chinese: 金朝; pinyin: Jīn Cháo) or Jin Empire (Chinese: 金國; pinyin: Jīn Guó; Jurchen: Anchun or Alchun[3] Gurun), officially known as the Great Jin (Chinese: 大金; pinyin: Dà Jīn), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 1115 and 1234. Its name is sometimes written as Kin, Jinn, or Chin[4] in English to differentiate it from an earlier Jìn dynasty whose name is rendered identically in Hanyu Pinyin without the tone marking.[5] It is also sometimes called the "Jurchen dynasty" or the "Jurchen Jin", because members of the ruling Wanyan clan were of Jurchen descent.

Great Jin 大金 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1115–1234 | |||||||||||||||||||||

.png.webp) Location of Jin dynasty (blue ), c. 1141

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Circuits of Jin | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese (later Old Mandarin), Jurchen, Khitan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1115–1123 | Taizu (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1161–1189 | Shizong | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1234 | Modi (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval Asia | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Founded by Aguda | 28 January 1115 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Destruction of the Liao dynasty | 1125 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 January 1127 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Mongol invasion | 1211 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 February 1234 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1142 est. | 3,610,000 km2 (1,390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1186 est. | 4,750,000 km2 (1,830,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1186 est.[1] | 53,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Chinese coin, Chinese cash, and paper money See: Jin dynasty coinage (1115–1234) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The Jin emerged from Wanyan Aguda's rebellion against the Liao dynasty (916–1125), which held sway over northern China until the nascent Jin drove the Liao to the Western Regions, where they became known in historiography as the Western Liao. After vanquishing the Liao, the Jin launched a century-long campaign against the Han-led Song dynasty (960–1279), which was based in southern China. Over the course of their rule, the ethnic Jurchen emperors of the Jin dynasty adapted to Han customs, and even fortified the Great Wall against the rising Mongols. Domestically, the Jin oversaw a number of cultural advancements, such as the revival of Confucianism.

After spending centuries as vassals of the Jin, the Mongols invaded under Genghis Khan in 1211 and inflicted catastrophic defeats on the Jin armies. After numerous defeats, revolts, defections, and coups, they succumbed to Mongol conquest 23 years later in 1234.

Name

The Jin dynasty was officially known as the "Great Jin" at that time. Furthermore, the Jin emperors referred to their state as China, Zhongguo (中國), just as some other non-Han dynasties.[6] Non-Han rulers expanded the definition of "China" to include non-Han peoples in addition to Han people whenever they ruled China.[7] Jin documents indicate that the usage of "China" by dynasties to refer to themselves began earlier than previously thought.[8]

History

| Jin dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 金朝 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 大金 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Great Jin | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Khitan name | |||||||||||||||||

| Khitan | Nik, Niku | ||||||||||||||||

Origin

The Mohe are the ancestors of the Jin. the Mohe were called Wuji, the Wuji lived on the land of the Sushen people. There are seven Wuji tribes: Sumo, Boduo, Anchegu, Funie, Haoshi, Heishui, Baishan.

The progenitors of the Jurchen people is the Mohe people who lived in what is now Northeast China. The Mohe were a primarily sedentary people who practiced hunting, pig farming, and grew crops such as soybean, wheat, millet, and rice. Horses were rare in the region until the Tang period and pastoralism was not widespread until the 10th century under the domination of the Khitans. The Mohe exported reindeer products and may have rode them as well. They practiced mass slavery and used the slaves to aid in hunting and agricultural work.[9][10] The Tang described the Mohe as a fierce and uncultured people who used poisoned arrows.[11]

The two most powerful groups of Mohe were the Heishui Mohe in the north, named after the Heilong River, and the Sumo Mohe in the south, named after the Songhua River. From the Heishui Mohe emerged the Jurchens in the forested mountain areas of eastern Manchuria and Russia's Primorsky Krai.[12] The Wuguo ("Five Nations") federation that existed to the northeast of modern Jilin are also considered to be ancestors of the Jurchens.[13] The Jurchens were mentioned in historical records for the first time in the 10th century as tribute bearers to the Liao, Later Tang, and Song courts.[14] They practiced hunting, fishing, and kept domestic oxen while their primary export was horses.[13] They had no script, calendar, or offices during the mid-11th century.[15] The Jurchens were small political actors in the international system at the time. By the 10th century, the Jurchens had become vassals of the Liao dynasty but they also sent a number of tributary and trade missions to the Song capital of Kaifeng, which the Liao tried unsuccessfully to prevent.[16] Some Jurchens paid tribute to Goryeo and sided with the latter during the Khitan–Goryeo War. They offered tribute to both courts out of political necessity and for material benefits.[17]

In the 11th century there was widespread discontent against Khitan rule among the Jurchens as the Liao violently extorted annual tribute from the Jurchen tribes. Leveraging the Jurchens' desire for independence from the Khitans, chief Wugunai (1021–1074) of the Wanyan clan rose to prominence, dominating all of eastern Manchuria from Mount Changbai to the Wuguo tribes. According to tradition, Wugunai was a sixth generation descendant of Hanpu while his father held a military title from the Liao court, although the title did not confer or hold any real power. As described, Wugunai was a great warrior, eater, drinker, and lover of women. His grandson Aguda eventually founded the Jin dynasty.[15]

Wanyan Aguda

The Jin dynasty was created in modern Jilin and Heilongjiang by the Jurchen tribal chieftain Aguda in 1115. According to tradition, Aguda was a descendant of Hanpu. Aguda adopted the term for "gold" as the name of his state, itself a translation of "Anchuhu" River, which meant "golden" in Jurchen.[18] This river, known as Alechuka in modern Chinese, is a tributary of the Songhua River east of Harbin.[18] The Jurchens' early rulers were the Khitan-led Liao dynasty, which had held sway over modern north and northeast China and the Mongolian Plateau, for several centuries. In 1121, the Jurchens entered into the Alliance Conducted at Sea with the Han-led Northern Song dynasty and agreed to jointly invade the Liao dynasty. While the Song armies faltered, the Jurchens succeeded in driving the Liao to Central Asia. In 1125, after the death of Aguda, the Jin dynasty broke its alliance with the Song dynasty and invaded north China. When the Song dynasty reclaimed the Han-populated Sixteen Prefectures, they were "fiercely resisted" by the Han Chinese population there who had previously been under Liao rule, while when the Jurchens invaded that area, the Han Chinese did not oppose them at all and handed over the Southern Capital (present-day Beijing, then known as Yanjing) to them.[19] The Jurchens were supported by the anti-Song, Beijing-based noble Han clans.[20] The Han Chinese who worked for the Liao were viewed as hostile enemies by the Song dynasty.[21] Song Han Chinese also defected to the Jin.[22] One crucial mistake that the Song made during this joint attack was the removal of the defensive forest it originally built along the Song-Liao border. Because of the removal of this landscape barrier, in 1126/27, the Jin army marched quickly across the North China Plain to Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng).[23] On 9 January 1127, the Jurchens ransacked the Imperial palaces in Kaifeng, the capital of the Northern Song dynasty, capturing both Emperor Qinzong and his father, Emperor Huizong, who had abdicated in panic in the face of the Jin invasion. Following the fall of Bianjing, the succeeding Southern Song dynasty continued to fight the Jin dynasty for over a decade, eventually signing the Treaty of Shaoxing in 1141, which called for the cession of all Song territories north of the Huai River to the Jin dynasty and the execution of Song general Yue Fei in return for peace. The peace treaty was formally ratified on 11 October 1142 when a Jin envoy visited the Song court.[24]

Having conquered Kaifeng and occupied North China, the Jin later deliberately chose earth as its dynastic element and yellow as its royal color. According to the theory of the Five Elements (wuxing), the earth element follows the fire, the dynastic element of the Song, in the sequence of elemental creation. Therefore, this ideological move shows that the Jin regarded the Song reign of China was officially over and themselves as the rightful ruler of China Proper.[25]

Migration south

After taking over Northern China, the Jin dynasty became increasingly sinicised. About three million people, half of them Jurchens, migrated south into northern China over two decades, and this minority governed about 30 million people. The Jurchens were given land grants and organised into hereditary military units: 300 households formed a mouke (company) and 7–10 moukes formed a meng-an (battalion).[26] Many married Han Chinese, although the ban on Jurchen nobles marrying Han Chinese was not lifted until 1191. After Emperor Taizong died in 1135, the next three Jin emperors were grandsons of Aguda by three different princes. Emperor Xizong (r. 1135–1149) studied the classics and wrote Chinese poetry. He adopted Han Chinese cultural traditions, but the Jurchen nobles had the top positions.

Later in life, Emperor Xizong became an alcoholic and executed many officials for criticising him. He also had Jurchen leaders who opposed him murdered, even those in the Wanyan clan. In 1149 he was murdered by a cabal of relatives and nobles, who made his cousin Wanyan Liang the next Jin emperor. Because of the brutality of both his domestic and foreign policy, Wanyan Liang was posthumously demoted from the position of emperor. Consequently, historians have commonly referred to him by the posthumous name "Prince of Hailing".[27]

Rebellions in the north

Having usurped the throne, Wanyan Liang embarked on the program of legitimising his rule as an emperor of China. In 1153, he moved the empire's main capital from Huining Prefecture (south of present-day Harbin) to the former Liao capital, Yanjing (present-day Beijing).[27][28] Four years later, in 1157, to emphasise the permanence of the move, he razed the nobles' residences in Huining Prefecture.[27][28] Wanyan Liang also reconstructed the former Song capital, Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng), which had been sacked in 1127, making it the Jin's southern capital.[27]

Wanyan Liang also tried to suppress dissent by killing Jurchen nobles, executing 155 princes.[27] To fulfil his dream of becoming the ruler of all China, Wanyan Liang attacked the Southern Song dynasty in 1161. Meanwhile, two simultaneous rebellions erupted in Shangjing, at the Jurchens' former power base: led by Wanyan Liang's cousin, soon-to-be crowned Wanyan Yong, and the other of Khitan tribesmen. Wanyan Liang had to withdraw Jin troops from southern China to quell the uprisings. The Jin forces were defeated by Song forces in the Battle of Caishi and Battle of Tangdao. With a depleted military force, Wanyan Liang failed to make headway in his attempted invasion of the Southern Song dynasty. Finally he was assassinated by his own generals in December 1161, due to his defeats. His son and heir was also assassinated in the capital.[27]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Although crowned in October, Wanyan Yong (Emperor Shizong) was not officially recognised as emperor until the murder of Wanyan Liang's heir.[27] The Khitan uprising was not suppressed until 1164; their horses were confiscated so that the rebels had to take up farming. Other Khitan and Xi cavalry units had been incorporated into the Jin army. Because these internal uprisings had severely weakened the Jin's capacity to confront the Southern Song militarily, the Jin court under Emperor Shizong began negotiating for peace. The Treaty of Longxing (隆興和議) was signed in 1164 and ushered in more than 40 years of peace between the two empires.

In the early 1180s, Emperor Shizong instituted a restructuring of 200 meng'an units to remove tax abuses and help Jurchens. Communal farming was encouraged. The Jin Empire prospered and had a large surplus of grain in reserve. Although learned in Chinese classics, Emperor Shizong was also known as a promoter of Jurchen language and culture; during his reign, a number of Chinese classics were translated into Jurchen, the Imperial Jurchen Academy was founded, and the imperial examinations started to be offered in the Jurchen language.[29] Emperor Shizong's reign (1161–1189) was remembered by the posterity as the time of comparative peace and prosperity, and the emperor himself was compared to the mythological rulers Yao and Shun. Poor Jurchen families in the southern Routes (Daming and Shandong) Battalion and Company households tried to live the lifestyle of wealthy Jurchen families and avoid doing farming work by selling their own Jurchen daughters into slavery and renting their land to Han tenants. The Wealthy Jurchens feasted and drank and wore damask and silk. The History of Jin (Jinshi) says that Emperor Shizong of Jin took note and attempted to halt these things in 1181.[30]

Emperor Shizong's grandson, Emperor Zhangzong (r. 1189–1208), venerated Jurchen values, but he also immersed himself in Han Chinese culture and married an ethnic Han Chinese woman. The Taihe Code of law was promulgated in 1201 and was based mostly on the Tang Code. In 1207, the Southern Song dynasty attempted an invasion, but the Jin forces effectively repulsed them. In the peace agreement, the Song dynasty had to pay higher annual indemnities and behead Han Tuozhou, the leader of the hawkish faction in the Song imperial court.

Fall of Jin

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Starting from the early 13th century, the Jin dynasty began to feel the pressure of Mongols from the north. Genghis Khan first led the Mongols into Western Xia territory in 1205 and ravaged it four years later. In 1211 about 50,000 Mongol horsemen invaded the Jin Empire and began absorbing Khitan and Jurchen rebels. The Jin had a large army with 150,000 cavalry but abandoned the "western capital" Datong (see also the Battle of Yehuling). The next year the Mongols went north and looted the Jin "eastern capital", and in 1213 they besieged the "central capital", Zhongdu (present-day Beijing). In 1214 the Jin made a humiliating treaty but retained the capital. That summer, Emperor Xuanzong abandoned the central capital and moved the government to the "southern capital" Kaifeng, making it the official seat of the Jin dynasty's power.

In 1216, a hawkish faction in the Jin imperial court persuaded Emperor Xuanzong to attack the Song dynasty, but in 1219 they were defeated at the same place by the Yangtze River where Wanyan Liang had been defeated in 1161. The Jin dynasty now faced a two front war that they could not afford. Furthermore, Emperor Aizong won a succession struggle against his brother and then quickly ended the war and went back to the capital. He made peace with the Tanguts of Western Xia, who had been allied with the Mongols.

The Jurchen Jin emperor Wanyan Yongji's daughter, Jurchen Princess Qiguo was married to Mongol leader Genghis Khan in exchange for relieving the Mongol siege upon Zhongdu (Beijing) in the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty.[31]

Many Han Chinese and Khitans defected to the Mongols to fight against the Jin dynasty. Two Han Chinese leaders, Shi Tianze and Liu Heima (劉黑馬),[32] and the Khitan Xiao Zhala (蕭札剌) defected and commanded the three tumens in the Mongol army.[33] Liu Heima and Shi Tianze served Genghis Khan's successor, Ögedei Khan.[34] Liu Heima and Shi Tianxiang led armies against Western Xia for the Mongols.[35] There were four Han tumens and three Khitan tumens, with each tumen consisting of 10,000 troops. The three Khitan generals Shimo Beidi'er (石抹孛迭兒), Tabuyir (塔不已兒), and Xiao Zhongxi (蕭重喜; Xiao Zhala's son) commanded the three Khitan tumens and the four Han generals Zhang Rou (張柔), Yan Shi (嚴實), Shi Tianze and Liu Heima commanded the four Han tumens under Ögedei Khan.[36][37][38][39]

Shi Tianze was a Han Chinese who lived under Jin rule. Inter-ethnic marriage between Han Chinese and Jurchens became common at this time. His father was Shi Bingzhi (史秉直). Shi Bingzhi married a Jurchen woman (surname Nahe) and a Han Chinese woman (surname Zhang); it is unknown which of them was Shi Tianze's mother.[40] Shi Tianze was married to two Jurchen women, a Han Chinese woman, and a Korean woman, and his son Shi Gang was born to one of his Jurchen wives.[41] His Jurchen wives' surnames were Monian and Nahe, his Korean wife's surname was Li, and his Han Chinese wife's surname was Shi.[40] Shi Tianze defected to the Mongol forces upon their invasion of the Jin dynasty. His son, Shi Gang, married a Keraite woman; the Keraites were Mongolified Turkic people and considered as part of the "Mongol nation".[41][42] Shi Tianze, Zhang Rou, Yan Shi and other Han Chinese who served in the Jin dynasty and defected to the Mongols helped build the structure for the administration of the new Mongol state.[43]

The Mongols created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops, and another army out of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[44]

Genghis Khan died in 1227 while his armies were attacking Western Xia. His successor, Ögedei Khan, invaded the Jin dynasty again in 1232 with assistance from the Southern Song dynasty. The Jurchens tried to resist; but when the Mongols besieged Kaifeng in 1233, Emperor Aizong fled south to the city of Caizhou. A Song–Mongol allied army surrounded the capital, and the next year Emperor Aizong committed suicide by hanging himself to avoid being captured in the Mongols besieged Caizhou, ending the Jin dynasty in 1234.[27] The territory of the Jin dynasty was to be divided between the Mongols and the Song dynasty. However, due to lingering territorial disputes, the Song dynasty and the Mongols eventually went to war with one another over these territories.

In Empire of The Steppes, René Grousset reports that the Mongols were always amazed at the valour of the Jurchen warriors, who held out until seven years after the death of Genghis Khan.

Military

_flags_(51169543864).png.webp)

Contemporary Chinese writers ascribed Jurchen success in overwhelming the Liao and Northern Song dynasties mainly to their cavalry. Already during Aguda's rebellion against the Liao dynasty, all Jurchen fighters were mounted. It was said that the Jurchen cavalry tactics were a carryover from their hunting skills.[45] Jurchen horsemen were provided with heavy armor; on occasions, they would use a team of horses attached to each other with chains (Guaizi Ma).[45]

Ethnic Bohai were an important element of not only civil but military administration in the Jin dynasty from its earliest stages. After annexing the Bohai rebel regime of Gao Yongchang, the Jin moved to attract Bohai recruits by sending out two Bohai, Liang Fu (梁福) and Wodala (斡荅剌) to encourage their compatriots to join the Jin, using the slogan "Jurchen and Bohai are originally of the same family" (女真渤海本同一家). Da Gao (大㚖), a descendant of Bohai royalty, was a major military commander in the Jin, commanding 8 meng-an of Bohai troops, and excelled in battle against the Song army. The Bohai were admired for their martial skills: "full of cunning, surpassing other nations in courage."[46]

As the Liao dynasty fell apart and the Song dynasty retreated beyond the Yangtze, the army of the new Jin dynasty absorbed many soldiers who formerly fought for the Liao or Song dynasties.[45] The new Jin empire adopted many of the Song military's weapons, including various machines for siege warfare and artillery. In fact, the Jin military's use of cannons, grenades, and even rockets to defend besieged Kaifeng against the Mongols in 1233 is considered the first ever battle in human history in which gunpowder was used effectively, even though it failed to prevent the eventual Jin defeat.[45]

On the other hand, the Jin military was not particularly good at naval warfare. Both in 1129–30 and in 1161 Jin forces were defeated by the Southern Song navies when trying to cross the Yangtze River into the core Southern Song territory (see Battle of Tangdao and Battle of Caishi), even though for the latter campaign the Jin had equipped a large navy of their own, using Han Chinese shipbuilders and even Han Chinese captains who had defected from the Southern Song.[45] Prince Hailing was the first northern conquest dynasty leader to attempt to expand into naval technology, to attack the waterways leading to southern China.[47]

In 1130, the Jin army reached Hangzhou and Ningbo in southern China. But heavy Chinese resistance and the geography of the area halted the Jin advance, and they were forced to retreat and withdraw, and they had not been able to escape the Song navy when trying to return until they were directed by a Han Chinese defector who helped them escape in Zhenjiang. Southern China was then cleared of the Jurchen forces.[48][49]

The Jin military was organised through the meng-an mou-k'o (meng'an mouke) system, seemingly similar to the later Eight Banners of the Qing dynasty. Meng-an is from the Mongol word for thousand, mingghan (see Military of the Yuan dynasty) while mou-k'o means clan or tribe. Groups of fifty households known as p'u-li-yen were grouped together as a mou-k'o, while seven to ten mou-k'o formed a meng-an, and several meng-an were grouped into a wanhu, Chinese for Ten Thousand Households. This was not only a military structure but also grouped all Jurchen households for economic and administrative functions. Khitans and Han Chinese soldiers who had defected to the Jin dynasty were also assigned into their own meng-an. All male members of the households were required to serve in the military; the servants of the household would serve as auxiliaries to escort their masters in battle. The numbers of Han Chinese soldiers in the Jin's armies seemed to be very significant.[50] The headships of the meng-an were initially the economic basis of the Jurchen aristocracy; some of the meng-an became private armies of hereditary imperial princes, seizing properties and challenging the throne. Jurchen military commanders were largely hereditary Jurchen nobles, and were given power over the local civilian governors where they were garrisoned. Prince Hailing abolished these autonomous positions, brutally suppressing potential threats, and thus established a more centralized Chinese-style model.[47] In 1140 sedentary populations such as the Han and Bohai were discharged from the meng-an system, and in 1163 the Khitans were discharged due to rebellion, although the Khitans who remained loyal were declared exempted from removal a few months later.[51] After the meng-an forces declined in effectiveness, ad hoc Chinese irregulars called Zhongxiao Jun (filial and loyal troops) were raised to fight the Mongols. They were known for their courage but also ill-discipline.[52]

The "Hulubojilie" (忽魯勃極列, from Jurchen gurun begile) was the army commander's title. "Bojilie" was the title of tribal chiefs.[53] When the population was mobilized for war, the Bojilie took on military command of the meng-an, which was the name of both the military unit and the title of its commander. The leadership of the dynasty was directed by the Council of Great Chieftains (Bojilie) until 1134 when Wuqimai dismantled it.[54]

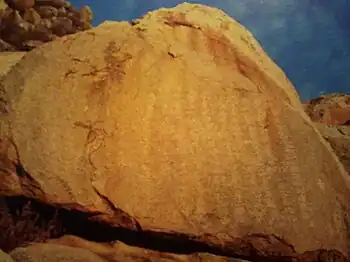

Jin Great Wall

In order to prevent incursion from the Mongols, a large construction program was launched. The records show that two important sections of the Great Wall were completed by the Jurchens.

The Great Wall as constructed by the Jurchens differed from the previous dynasties. Known as the Border Fortress or the Boundary Ditch of the Jin, it was formed by digging ditches within which lengths of wall were built. In some places subsidiary walls and ditches were added for extra strength. The construction was started in about 1123 and completed by about 1198. The two sections attributable to the Jin dynasty are known as the Old Mingchang Walls and New Great Walls, together stretching more than 2,000 kilometres in length.[55]

Government

The government of the Jin dynasty merged Jurchen customs with institutions adopted from the Liao and Song dynasties.[56] The pre-dynastic Jurchen government was based on the quasi-egalitarian tribal council.[57] Jurchen society at the time did not have a strong political hierarchy. The Shuo Fu (說郛) records that the Jurchen tribes were not ruled by central authority and locally elected their chieftains.[56] Tribal customs were retained after Aguda united the Jurchen tribes and formed the Jin dynasty, coexisting alongside more centralised institutions.[58] The Jin dynasty had five capitals, a practice they adopted from the Balhae and the Liao.[59] The Jin had to overcome the difficulties of controlling a multicultural empire composed of territories once ruled by the Liao and Northern Song. The solution of the early Jin government was to establish separate government structures for different ethnic groups.[60]

Culture

Because the Jin had few contacts with its southern neighbour, the Song dynasty, different cultural developments took place in both states. Within Confucianism, the "Learning of the Way" that developed and became orthodox in Song did not take root in Jin. Jin scholars put more emphasis on the work of northern Song scholar and poet Su Shi (1037–1101) than on Zhu Xi's (1130–1200) scholarship, which constituted the foundation of the Learning of the Way.[61]

Architecture

The Jin pursued a revival of Tang dynasty urban design with architectural projects in Kaifeng and Zhongdu (modern Beijing), building for instance a bell tower and drum tower to announce the night curfew (which was revived after being abolished under the Song).[62] The Jurchens followed Khitan precedent of living in tents amidst the Chinese-style architecture, which were in turn based on the Song dynasty Kaifeng model.[63]

Religion

_fresco_in_Ch'ung-fu_Temple%252C_Shuo-chou_1.jpg.webp)

Taoism

A significant branch of Taoism called the Quanzhen School was founded under the Jin by Wang Zhe (1113–1170), a Han Chinese man who founded formal congregations in 1167 and 1168. Wang took the nickname of Wang Chongyang (Wang "Double Yang") and the disciples he took were retrospectively known as the "seven patriarchs of Quanzhen". The flourishing of ci poetry that characterized Jin literature was tightly linked to Quanzhen, as two-thirds of the ci poetry written in Jin times was composed by Quanzhen Taoists.

.jpg.webp)

The Jin state sponsored an edition of the Taoist Canon that is known as the Precious Canon of the Mysterious Metropolis of the Great Jin (Da Jin Xuandu baozang 大金玄都寶藏). Based on a smaller version of the Canon printed by Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1125) of the Song dynasty, it was completed in 1192 under the direction and support of Emperor Zhangzong (r. 1190–1208).[64] In 1188, Zhangzong's grandfather and predecessor Shizong (r. 1161–1189) had ordered the woodblocks for the Song Canon transferred from Kaifeng (the former Northern Song capital that had now become the Jin "Southern Capital") to the Central Capital's "Abbey of Celestial Perpetuity" or Tianchang guan 天長觀, on the site of what is now the White Cloud Temple in Beijing.[64] Other Daoist writings were also moved there from another abbey in the Central Capital.[64] Zhangzong instructed the abbey's superintendent Sun Mingdao 孫明道 and two civil officials to prepare a complete Canon for printing.[64] After sending people on a "nationwide search for scriptures" (which yielded 1,074 fascicles of text that was not included in the Huizong edition of the Canon) and securing donations for printing, in 1192 Sun Mingdao proceeded to cut the new woodblocks.[65] The final print consisted of 6,455 fascicles.[66] Though the Jin emperors occasionally offered copies of the Canon as gifts, not a single fragment of it has survived.[66]

Buddhism

A Buddhist Canon or "Tripitaka" was also produced in Shanxi, the same place where an enhanced version of the Jin-sponsored Taoist Canon would be reprinted in 1244.[67] The project was initiated in 1139 by a Buddhist nun named Cui Fazhen, who swore (and allegedly "broke her arm to seal the oath") that she would raise the necessary funds to make a new official edition of the Canon printed by the Northern Song.[68] Completed in 1173, the Jin Tripitaka counted about 7,000 fascicles, "a major achievement in the history of Buddhist private printing."[68] It was further expanded during the Yuan.[68]

Buddhism thrived during the Jin, both in its relation with the imperial court and in society in general.[69] Many sutras were also carved on stone tablets.[70] The donors who funded such inscriptions included members of the Jin imperial family, high officials, common people, and Buddhist priests.[70] Some sutras have only survived from these carvings, which are thus highly valuable to the study of Chinese Buddhism.[70] At the same time, the Jin court sold monk certificates for revenue. This practice was initiated in 1162 by Shizong to fund his wars, and stopped three years later when war was over.[71] His successor Zhanzong used the same method to raise military funds in 1197 and one year later to raise money to fight famine in the Western Capital.[71] The same practice was used again in 1207 (to fight the Song and more famine) as well as under the reigns of emperors Weishao (r. 1209–1213) and Xuanzong (r. 1213–1224) to fight the Mongols.[72]

Fashion

List of emperors

| Temple name | Posthumous name1 | Jurchen name | Chinese name | Years of reign | Era name(s) and Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taizu (太祖) | Wuyuan (武元) | Aguda (阿骨打) | Min (旻) | 1115–1123 | Shouguo (收國; 1115–1116) Tianfu (天輔; 1117–1123) |

| Taizong (太宗) | Wenlie (文烈) | Wuqimai (吳乞買) | Sheng (晟) | 1123–1135 | Tianhui (天會; 1123–1135) |

| Xizong (熙宗) | Xiaocheng (孝成) | Hela (合剌) | Dan (亶) | 1135–1149 | Tianhui (天會; 1135–1138) Tianjuan (天眷; 1138–1141) Huangtong (皇統; 1141–1149) |

| None | – | Digunai (迪古乃) | Liang (亮) | 1149–1161 | Tiande (天德, 1149–1153) Zhenyuan (貞元; 1153–1156) Zhenglong (正隆; 1156–1161) |

| Shizong (世宗) | Renxiao (仁孝) | Wulu (烏祿) | Yong (雍) | 1161–1189 | Dading (大定; 1161–1189) |

| Zhangzong 章宗 |

Guangxiao (光孝) | Madage (麻達葛) | Jing (璟) | 1189–1208 | Mingchang (明昌; 1190–1196) Cheng'an (承安; 1196–1200) Taihe (泰和; 1200–1208) |

| None | – | Unknown | Yongji (永濟) | 1208–1213 | Da'an (大安; 1209–1212) Chongqing (崇慶; 1212–1213) Zhining (至寧; 1213) |

| Xuanzong 宣宗 |

Shengxiao (聖孝) | Wudubu (吾睹補) | Xun (珣) | 1213–1224 | Zhenyou (貞祐; 1213–1217) Xingding (興定; 1217–1222) Yuanguang (元光; 1222–1224) |

| Aizong (哀宗, official) Zhuangzong (莊宗, unofficial) Minzong (閔宗, unofficial) Yizong (義宗, unofficial) |

None | Ningjiasu (寧甲速) | Shouxu (守緒) | 1224–1234 | Zhengda (正大; 1224–1232) Kaixing (開興; 1232) Tianxing (天興; 1232–1234) |

| None | None | Hudun (呼敦) | Chenglin (承麟) | 1234 | Shengchang (盛昌; 1234) |

| 1: For full posthumous names, see the articles for individual emperors. | |||||

Emperors family tree

| Emperors family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

|

References

Citations

- Twitchett & Fairbank 1994, p. 40.

- "Jin". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- René Grousset (1970), A History of Central Asia (reprint, illustrated ed.), Rutgers University Press, p. 136, ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1

- Franke 1994, pp. 215–320.

- Lipschutz, Leonard (2000). Century-By-Century: A Summary of World History. iUniverse. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-595-12578-4. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- Zhao 2006, p. 7.

- Zhao 2006, p. 6.

- Zhao 2006, p. 24.

- Gorelova 2002, pp. 13–14.

- Crossley 1997, p. 17.

- Crossley 1997, p. 124.

- Crossley 1997, p. 18–20.

- Franke 1994, p. 217.

- Franke 1994, p. 218.

- Franke 1994, p. 220.

- Franke 1994, p. 219.

- Breuker 2010, pp. 220–221.

- Franke 1994, p. 221.

- Franke & Twitchett 1994, p. 39.

- Tillman 1995a, pp. 28–.

- Elliott, Mark (2012). "8. Hushuo The Northern Other and the Naming of the Han Chinese" (PDF). In Mullaney, Tomhas S.; Leibold, James; Gros, Stéphane; Bussche, Eric Vanden (eds.). Critical Han Studies The History, Representation, and Identity of China's Majority. University of California Press. p. 186.

- Gernet 1996, pp. 358–.

- Chen, Yuan Julian (2018). "Frontier, Fortification, and Forestation: Defensive Woodland on the Song–Liao Border in the Long Eleventh Century". Journal of Chinese History. 2 (2): 313–334. doi:10.1017/jch.2018.7. ISSN 2059-1632.

- Hymes, Robert (2000). John Stewart Bowman (ed.). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- Chen, Yuan Julian (2014). "Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 44 (1): 325–364. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0000.

- Mark C. Elliot (2001). The Manchu Way: The eight banners and ethnic identity in late imperial China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 60.

- Beck, Sanderson. "Liao, Xi Xia, and Jin Dynasties 907–1234". China 7 BC To 1279.

- Tao (1976), p. 44

- Tao (1976), Chapter 6. "The Jurchen Movement for Revival", pp. 69–83

- Schneider, Julia (2011). "The Jin Revisited: New Assessment of Jurchen Emperors". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies (41): 343–404. Retrieved 31 March 2023 – via JSTOR.

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-108-63662-9.

- Collectif (2002). Revue bibliographique de sinologie 2001. Éditions de l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales. p. 147.

- May, Timothy Michael (2004). The Mechanics of Conquest and Governance: The Rise and Expansion of the Mongol Empire, 1185–1265. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 50.

- Schram, Stuart Reynolds (1987). Foundations and Limits of State Power in China. European Science Foundation by School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 130.

- Gary Seaman; Daniel Marks (1991). Rulers from the steppe: state formation on the Eurasian periphery. Ethnographics Press, Center for Visual Anthropology, University of Southern California. p. 175.

- 胡小鹏 (2001). "窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨–兼论金元之际的汉地七万户" [A Study of XIAO Zha-la the Han Army Commander of 10,000 Families in the Year of 1229 during the Period of Khan (O)gedei]. 西北师大学报(社会科学版) PKUCSSCI [Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences)] (in Chinese). 38 (6). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-9162.2001.06.008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨–兼论金元之际的汉地七万户-国家哲学社会科学学术期刊数据库". Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "新元史/卷146 – 維基文庫,自由的圖書館". zh.wikisource.org.

- "作品相关 第二十九章 大库里台. 本章出自《草原特种兵》" [Chapter 29 Big Curry Terrace. This chapter is from Grassland Special Forces] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- Igor de Rachewiltz, ed. (1993). In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yüan Period (1200–1300). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 41.

- J. Ganim; S. Legassie, eds. (2013). Cosmopolitanism and the Middle Ages. Springer. p. 47.

- Watt, James C. Y. (2010). The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 14.

- Chan, Hok-Lam (1997). "A Recipe to Qubilai Qa'an on Governance: The Case of Chang Te-hui and Li Chih". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 7 (2): 257–283. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008877. S2CID 161851226.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 66.

- Tao (1976), Chapter 2. "The Rise of the Chin dynasty", pp. 21–24

- Jesse D. Sloane (2014). "Mapping a Stateless Nation: "Bohai" Identity in the Twelfth to Fourteenth Centuries". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 44: 365–403. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0003. S2CID 164130734.

- Frederick W. Mote (1999). Imperial China, 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 231–235. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Gernet (1996), p. 357. "Nanking and Hangchow were taken by assault in 1129 and in 1130 the Jürchen ventured as far as Ning-po, in the north-eastern tip of Chekiang."

- René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia (reprint, illustrated ed.). Rutgers University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

The emperor Kao-tsung had taken flight to Ningpo (then known as Mingchow) and later to the port of Wenchow, south of Chekiang. From Nanking the Kin general Wu-chu hastened in pursuit and captured Hangchow and Ningpo (end of 1129 and beginning of 1130. However, the Kin army, consisting entirely of cavalry, had ventured too far into this China of the south with its flooded lands, intersecting rivers, paddy fields and canals, and dense population which harassed and encircled it. We-chu, leader of the Kin troops, sought to return north but was halted by the Yangtze, now wide as a sea and patrolled by Chinese flotillas. At last a traitor showed him how he might cross the river near Chenkiang, east of Nanking (1130).

- Franke 1994, pp. 273–277.

- Frederick W. Mote (1999). Imperial China, 900–1800. Harvard University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Peter Connolly, John Gillingham, John Lazenby (2016). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare. Routledge. p. 356. ISBN 978-1-135-93674-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Shi Youwei (2020). Loanwords in the Chinese Language. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-000-29351-7.

- Frederick W. Mote (1999). Imperial China, 900–1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 217, 227. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- "Great Wall of Jin Dynasty (1115–1234)". TravelChinaGuide.

- Franke 1994, p. 265.

- Franke 1994, pp. 265–266.

- Franke 1994, p. 266.

- Franke 1994, p. 270.

- Franke 1994, p. 267.

- Tillman 1995b, pp. .

- Robert S. Nelson, Margaret Olin (2003). Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade. University of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-226-57158-4.

- Toby Lincoln (2021). An Urban History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-107-19642-1.

- Boltz 2008, p. 291.

- Boltz 2008, pp. 291–92.

- Boltz 2008, p. 292.

- Yao 1995, p. 174; Goossaert 2008, p. 916 (both Buddhist Canon and Daoist Canon printed in Shanxi).

- Yao 1995, p. 174.

- Yao 1995, p. 173.

- Yao 1995, p. 175.

- Yao 1995, p. 161.

- Yao 1995, pp. 161–62.

Sources

- Boltz, Judith (2008), "Da Jin Xuandu baozang 大金玄嘟寶藏", in Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 291–92, ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7.

- Breuker, Remco E. (2010), Establishing a Pluralist Society in Medieval Korea, 918-1170: History, Ideology and Identity in the Koryŏ Dynasty, vol. 1 of Brill's Korean Studies Library, Leiden: Brill, pp. 220-221, ISBN 978-90-04-18325-4

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1997), The Manchus, Blackwell Publishers

- Franke, Herbert (1994), "The Chin dynasty", in Denis C. Twitchett; John King Fairbank (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368, Cambridge University Press, pp. 215–320, ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis C. (1994), "Introduction", in Denis C. Twitchett; John King Fairbank (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–42, ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- Goossaert, Vincent (2008), "Song Defang 宋德方", in Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 915–16, ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7.

- Gorelova, Liliya M., ed. (2002), Manchu Grammar, Part 8, Handbook of Oriental Studies, vol. 7, Brill Academic Pub, pp. 13–14, ISBN 90-04-12307-5

- Tao, Jing-shen (1976), The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-95514-8

- Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland (1995a). "An Overview of Chin History and Institutions". In Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland; West, Stephen H. (eds.). China Under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History. SUNY Press. pp. 23–38. ISBN 978-0-7914-2273-1.

- Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland (1995b), "Confucianism under the Chin and the Impact of Sung Confucian Tao-hsüeh", in Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland; West, Stephen H. (eds.), China under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History, SUNY Press, pp. 71–114, ISBN 978-0-7914-2273-1

- Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King, eds. (1994), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5, retrieved 10 March 2014 (hardcover)

- Yao, Tao-chung (1995), "Buddhism and Taoism under the Chin", in Hoyt Cleveland Tillman; Stephen H. West (eds.), China under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pp. 145–80, ISBN 978-0-7914-2274-8

- Zhao, Gang (2006), "Reinventing China: Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century", Modern China, 32 (1): 3–30, doi:10.1177/0097700405282349, JSTOR 20062627, S2CID 144587815

Further reading

- Franke, Herbert (1971), "Chin Dynastic History Project", Sung Studies Newsletter, 3 (3): 36–37, JSTOR 23497078.

- Schneider, Julia (2011), "The Jin Revisited: New Assessment of Jurchen Emperors", Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 41 (41): 343–404, doi:10.1353/sys.2011.0030, hdl:1854/LU-2045182, JSTOR 23496214, S2CID 162237648

External links

Media related to Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) at Wikimedia Commons