Louis Agassiz

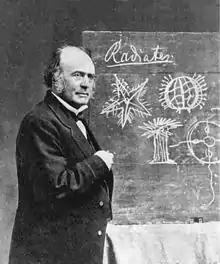

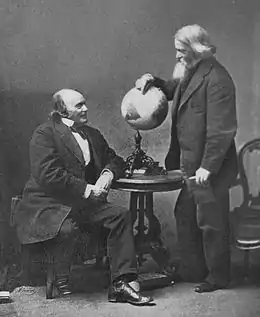

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (/ˈæɡəsi/ AG-ə-see; French: [aɡasi]) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Louis Agassiz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 28, 1807 |

| Died | December 14, 1873 (aged 66) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Education | University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (PhD) University of Munich |

| Known for | Ice age, Polygenism |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3, including Alexander and Pauline |

| Awards | Wollaston Medal (1836) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | University of Neuchâtel Harvard University Cornell University |

| Doctoral advisor | Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius |

| Other academic advisors | Ignaz Döllinger, Georges Cuvier |

| Notable students | William Stimpson, William Healey Dall, Carl Vogt,[1] David Starr Jordan |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Agassiz, Ag., L. Ag., Agass. |

| Signature | |

| |

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he received a PhD at Erlangen and a medical degree in Munich. After studying with Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt in Paris, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. He emigrated to the United States in 1847 after visiting Harvard University. He went on to become professor of zoology and geology at Harvard, to head its Lawrence Scientific School, and to found its Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Agassiz is known for observational data gathering and analysis. He made institutional and scientific contributions to zoology, geology, and related areas, including multivolume research books running to thousands of pages. He is particularly known for his contributions to ichthyological classification, including of extinct species such as megalodon, and to the study of historical geology, including the founding of glaciology.

His theories on human, animal and plant polygenism have been criticised as implicitly supporting scientific racism.

Early life

Louis Agassiz was born in the village of Môtier (fr) (now part of Haut-Vully which merged into Mont-Vully in 2016) in the Swiss Canton of Fribourg.[2] He was the son of a pastor,[3] Louis Rudolphe and his wife, Rose Mayor.

His father was a Protestant clergyman, as had been his progenitors for six generations, and his mother was the daughter of a physician and an intellectual in her own right, who had assisted her husband in the education of her boys.[2] He was educated at home[2] until he spent four years at secondary school in Bienne, which he entered in 1818 and completed his elementary studies in Lausanne. Agassiz studied at the Universities of Zürich, Heidelberg and Munich. At the last one, he extended his knowledge of natural history, especially of botany. In 1829, he received the degree of doctor of philosophy at Erlangen and, in 1830, that of doctor of medicine at Munich.[4] Moving to Paris, he came under the tutelage of Alexander von Humboldt and later received his financial benevolence.[5] Humboldt and Georges Cuvier launched him on his careers of respectively geology and zoology.[6] Ichthyology soon became a focus of Agassiz's life's work.[6]

Early work

In 1819 to 1820, the German biologists Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius undertook an expedition to Brazil. They returned home to Europe with many natural objects, including an important collection of the freshwater fish of Brazil, especially of the Amazon River. Spix, who died in 1826, likely from a tropical disease, did not live long enough to work out the history of those fish, and Martius selected Agassiz for this project.

Agassiz threw himself into the work with an enthusiasm that would go on to characterize the rest of his life's work. The task of describing the Brazilian fish was completed and published in 1829. It was followed by research into the history of fish found in Lake Neuchâtel. Enlarging his plans, he in 1830 issued a prospectus of a History of the Freshwater Fish of Central Europe. In 1839, however, the first part of the publication appeared, and it was completed in 1842.[4]

In November 1832, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel, at a salary of about US$400 and declined brilliant offers in Paris because of the leisure for private study that that position afforded him.[7] The fossil fish in the rock of the surrounding region, the slates of Glarus and the limestones of Monte Bolca, soon attracted his attention. At the time, very little had been accomplished in their scientific study. Agassiz as early as 1829, planned the publication of a work. More than any other, it would lay the foundation of his worldwide fame. Five volumes of his Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (Research on Fossil Fish) were published from 1833 to 1843. They were magnificently illustrated, chiefly by Joseph Dinkel.[8] In gathering materials for that work, Agassiz visited the principal museums in Europe. Meeting Cuvier in Paris, he received much encouragement and assistance from him.[4]

In 1833, he married Cecile Braun, the sister of his friend Alexander Braun and established his household at Neuchâtel. Trained to scientific drawing by her brothers, his wife was of the greatest assistance to Agassiz, with some of the most beautiful plates in fossil and freshwater fishes being drawn by her.[7]

Agassiz found that his palaeontological analyses required a new ichthyological classification. The fossils that he examined rarely showed any traces of the soft tissues of fish but instead, consisted chiefly of the teeth, scales, and fins, with the bones being perfectly preserved in comparatively few instances. He therefore adopted a classification that divided fish into four groups (ganoids, placoids, cycloids, and ctenoids), based on the nature of the scales and other dermal appendages. That did much to improve fish taxonomy, but Agassiz's classification has since been superseded.[4]

With Louis de Coulon, both father and son, he founded the Societé des Sciences Naturelles, of which he was the first secretary and in conjunction with the Coulons also arranged a provisional museum of natural history in the orphan's home.[7] Agassiz needed financial support to continue his work. The British Association and the Earl of Ellesmere, then Lord Francis Egerton, stepped in to help. The 1290 original drawings made for the work were purchased by the Earl and presented by him to the Geological Society of London. In 1836, the Wollaston Medal was awarded to Agassiz by the council of that society for his work on fossil ichthyology. In 1838, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society. Meanwhile, invertebrate animals engaged his attention. In 1837, he issued the "Prodrome" of a monograph on the recent and fossil Echinodermata, the first part of which appeared in 1838; in 1839–1840, he published two quarto volumes on the fossil echinoderms of Switzerland; and in 1840–1845, he issued his Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (Critical Studies on Fossil Mollusks).[4]

Before Agassiz's first visit to England in 1834, Hugh Miller and other geologists had brought to light the remarkable fossil fish of the Old Red Sandstone of the northeast of Scotland. The strange forms of Pterichthys, Coccosteus, and other genera were then made known to geologists for the first time. They were of intense interest to Agassiz and formed the subject of a monograph by him published in 1844–1(45: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie (Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone, or Devonian System of the British Isles and of Russia).[4] In the early stages of his career in Neuchatel, Agassiz also made a name for himself as a man who could run a scientific department well. Under his care, the University of Neuchâtel soon became a leading institution for scientific inquiry.

In 1842 to 1846, Agassiz issued his Nomenclator Zoologicus, a classification list with references of all names used in zoological genera and groups.

He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1843.[9]

Ice age

The vacation of 1836 was spent by Agassiz and his wife in the little village of Bex, where he met Jean de Charpentier and Ignaz Venetz. Their recently announced glacial theories had startled the scientific world, and Agassiz returned to Neuchâtel as an enthusiastic convert.[10] In 1837, Agassiz proposed that the Earth had been subjected to a past ice age.[11] He presented the theory to the Helvetic Society that ancient glaciers flowed outward from the Alps, and even larger glaciers had covered the plains and mountains of Europe, Asia, and North America and smothered the entire Northern Hemisphere in a prolonged ice age. In the same year, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Before that proposal, Goethe, de Saussure, Ignaz Venetz, Jean de Charpentier, Karl Friedrich Schimper, and others had studied the glaciers of the Alps, and Goethe,[12] Charpentier, and Schimper[11] had even concluded that the erratic blocks of alpine rocks scattered over the slopes and summits of the Jura Mountains had been moved there by glaciers. Those ideas attracted the attention of Agassiz, and he discussed them with Charpentier and Schimper, whom he accompanied on successive trips to the Alps. Agassiz even had a hut constructed upon one of the Aar Glaciers and for a time made it his home to investigate the structure and movements of the ice.[4]

Agassiz visited England, and with William Buckland, the only English naturalist who shared his ideas, made a tour of the British Isles in search of glacial phenomena, and became satisfied that his theory of an ice age was correct.[10] In 1840, Agassiz published a two-volume work, Études sur les glaciers ("Studies on Glaciers").[13] In it, he discussed the movements of the glaciers, their moraines, and their influence in grooving and rounding the rocks and in producing the striations and roches moutonnées seen in Alpine-style landscapes. He accepted Charpentier and Schimper's idea that some of the alpine glaciers had extended across the wide plains and valleys of the Aar and Rhône, but he went further by concluding that in the recent past, Switzerland had been covered with one vast sheet of ice originating in the higher Alps and extending over the valley of northwestern Switzerland to the southern slopes of the Jura. The publication of the work gave fresh impetus to the study of glacial phenomena in all parts of the world.[14]

Familiar then with recent glaciation, Agassiz and the English geologist William Buckland visited the mountains of Scotland in 1840. There, they found clear evidence in different locations of glacial action. The discovery was announced to the Geological Society of London in successive communications. The mountainous districts of England, Wales, and Ireland were understood to have been centres for the dispersion of glacial debris. Agassiz remarked "that great sheets of ice, resembling those now existing in Greenland, once covered all the countries in which unstratified gravel (boulder drift) is found; that this gravel was in general produced by the trituration of the sheets of ice upon the subjacent surface, etc."[15]

In his later years, Agassiz applied his glacial theories to the geology of the Brazilian tropics, including the Amazon. Agassiz began with a working hypothesis which could be tested by the results of fieldwork to find either inconclusive, or conclusively supporting or refuting evidence. A hypothesis that can be conclusively refuted is better than a hypothesis that difficult to test. Agassiz had a close association with his student and field assistant, the geologist Charles Hartt who eventually refuted Agassiz's theories about the Amazon based on his fieldwork there. Instead of evidence for any glacial processes, he found chemically weathered sediments from marine and tropical fluvial, not glacial, processes, a finding that later geologists confirmed.[16] Agassiz hypothesis that the Amazon was affected by the Last Glacial Maximum was correct, although the mechanism causing the effect was non-glacial. The Amazon rainforest was split into two large blocks by extensive savanna during the LGM.

United States

With the aid of a grant of money from the king of Prussia, Agassiz crossed the Atlantic in the autumn of 1846 to investigate the natural history and geology of North America and to deliver a course of lectures on "The Plan of Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom"[17] by invitation from John Amory Lowell, at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Massachusetts. The financial offers that were presented to him in the United States induced him to settle there, where he remained to the end of his life.[15] He was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1846.[18]

In 1846, still married to Cecilie, who remained with their three children in Switzerland, Agassiz met Elizabeth Cabot Cary at a dinner. The two developed a romantic attachment, and when his wife died in 1848, they made plans to marry. The ceremony took place on April 25, 1850, in Boston, Massachusetts at King's Chapel. Agassiz brought his children to live with them, and Elizabeth raised and developed close relationships with her step-children. She had no children of her own.[19]

Agassiz had a mostly cordial relationship with the Harvard botanist Asa Gray despite their disagreements.[20] Agassiz believed each human race had been separately created,[21] but Gray, a supporter of Charles Darwin, believed in the shared evolutionary ancestry of all humans.[22] In addition, Agassiz was a member of the Scientific Lazzaroni, a group of mostly physical scientists who wanted American academia to mimic the more autocratic academic structures of European universities, but Gray was a staunch opponent of that group.

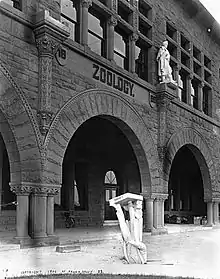

Agassiz's engagement for the Lowell Institute lectures precipitated the establishment in 1847 of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard University, with Agassiz as its head.[23] Harvard appointed him professor of zoology and geology, and he founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology there in 1859 and served as its first director until his death in 1873. During his tenure at Harvard, Agassiz studied the effect of the last ice age in North America. In August 1857, Agassiz was offered the chair of palaeontology in the Museum of Natural History, Paris, which he refused. He was later decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honor.[24]

Agassiz continued his lectures for the Lowell Institute. In succeeding years, he gave lectures on "Ichthyology" (1847–1848), "Comparative Embryology" (1848–1849), "Functions of Life in Lower Animals" (1850–1851), "Natural History" (1853–1854), "Methods of Study in Natural History" (1861–1862), "Glaciers and the Ice Period" (1864–1865), "Brazil" (1866–1867), and "Deep Sea Dredging" (1869–1870).[25] In 1850, he had married Elizabeth Cabot Cary, who later wrote introductory books about natural history and a lengthy biography of her husband after he had died.[26]

Agassiz served as a nonresident lecturer at Cornell University while he was also on faculty at Harvard.[27] In 1852, he accepted a medical professorship of comparative anatomy at Charlestown, Massachusetts, but he resigned in two years.[15] From then on, Agassiz's scientific studies dropped off, but he became one of the best-known scientists in the world. By 1857, Agassiz was so well-loved that his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote "The Fiftieth Birthday of Agassiz" in his honor and read it at a dinner given for Agassiz by the Saturday Club in Cambridge.[15] Agassiz's own writing continued with four (of a planned 10) volumes of Natural History of the United States, published from 1857 to 1862. He also published a catalog of papers in his field, Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae, in four volumes between 1848 and 1854.[28][29][30][31]

Stricken by ill health in the 1860s, Agassiz resolved to return to the field for relaxation and to resume his studies of Brazilian fish. In April 1865, he led the Thayer Expedition to Brazil. While there, he commissioned two photographers, Augusto Stahl and Georges Leuzinger, to accompany the expedition and produce somatological images of Indigenous people and enslaved Africans and Black people.[32] After his return in August 1866, an account of the expedition, A Journey in Brazil,[33] was published in 1868. In December 1871, he made a second eight-month excursion, known as the Hassler expedition under the command of Commander Philip Carrigan Johnson (the brother of Eastman Johnson) and visited South America on its southern Atlantic and Pacific Seaboards. The ship explored the Magellan Strait, which drew the praise of Charles Darwin.[34]

Following the establishment of the first U.S. Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York City in 1866, Agassiz was called on to help settle disputes about animal behavior. He deemed the way turtles were shipped caused them suffering, while P.T. Barnum argued with Agassiz' support that his snakes would eat only live animals.[35]

His second wife, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, assisted him in preparing his A Journey in Brazil. Along with her stepson, Alexander Agassiz, she wrote Seaside Studies in Natural History and Marine Animals of Massachusetts.[24] Elizabeth wrote at the Strait that "the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them.... These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck."[36]

Family

From his first marriage to Cecilie Braun, Agassiz had two daughters, Ida and Pauline, and a son, Alexander.[37] In 1863, Agassiz's daughter Ida married Henry Lee Higginson, who later founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was a benefactor to Harvard and other schools. On November 30, 1860, Agassiz's daughter Pauline was married to Quincy Adams Shaw (1825–1908), a wealthy Boston merchant and later a benefactor to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[38] Pauline Agassiz Shaw later became a prominent educator, suffragist, and philanthropist.[39]

Later life

In the last years of his life, Agassiz worked to establish a permanent school in which zoological science could be pursued amid the living subjects of its study. In 1873, the private philanthropist John Anderson gave Agassiz the island of Penikese, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts (south of New Bedford), and presented him with $50,000 to endow it permanently as a practical school of natural science that would be especially devoted to the study of marine zoology.[15] The school collapsed soon after Agassiz's death but is considered to be a precursor of the nearby Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory.[40]

Agassiz had a profound influence on the American branches of his two fields and taught many future scientists who would go on to prominence, including Alpheus Hyatt, David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Ernest Ingersoll, William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Nathaniel Shaler, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, Alpheus Packard, and his son Alexander Emanuel Agassiz. He had a profound impact on the paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott and the natural scientist Edward S. Morse. Agassiz had a reputation for being a demanding teacher. He would allegedly "lock a student up in a room full of turtle-shells, or lobster-shells, or oyster-shells, without a book or a word to help him, and not let him out till he had discovered all the truths which the objects contained."[41] Two of Agassiz's most prominent students detailed their personal experiences under his tutelage: Scudder, in a short magazine article for Every Saturday,[42] and Shaler, in his Autobiography.[43] Those and other recollections were collected and published by Lane Cooper in 1917,[44] which Ezra Pound would draw on for his anecdote of Agassiz and the sunfish.[45]

In the early 1840s, Agassiz named two fossil fish species after Mary Anning (Acrodus anningiae and Belenostomus anningiae) and another after her friend, Elizabeth Philpot. Anning was a paleontologist known around the world for important finds, but because of her gender, she was often not formally recognized for her work. Agassiz was grateful for the help that the women gave him in examining fossil fish specimens during his visit to Lyme Regis in 1834.[46]

Agassiz died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1873 and was buried on the Bellwort Path at Mount Auburn Cemetery,[47] joined later by his wife. His monument is a boulder from a glacial moraine of the Aar near the site of the old Hôtel des Neuchâtelois, not far from the spot where his hut once stood. His grave is sheltered by pine trees from his old home in Switzerland.[15]

Legacy

The Cambridge elementary school north of Harvard University was named in his honor, and the surrounding neighborhood became known as "Agassiz" as a result. The school's name was changed to the Maria L. Baldwin School on May 21, 2002, because of concerns about Agassiz's involvement in scientific racism and to honor Maria Louise Baldwin, the African-American principal of the school, who served from 1889 to 1922.[48][49] The neighborhood, however, continued to be known as Agassiz.[50] c. 2009, neighborhood residents decided to rename the neighborhood's community council as the "Agassiz-Baldwin Community".[51] Then, in July 2021, culminating a two-year effort on the part of neighborhood residents, the Cambridge City Council voted unanimously to change the name to the Baldwin Neighborhood.[52] An elementary school, the Agassiz Elementary School in Minneapolis, Minnesota, existed from 1922 to 1981.[53]

Geological tributes

An ancient glacial lake that formed in central North America, Lake Agassiz, is named after him, as are Mount Agassiz in California's Palisades, Mount Agassiz in the Uinta Mountains of Utah, Agassiz Peak in Arizona, Agassiz Rock in Massachusetts, and the Agassizhorn in the Bernese Alps in his native Switzerland. Agassiz Glacier in Montana, Agassiz Creek in Glacier National Park, Agassiz Glacier in the Saint Elias Mountains of Alaska, and Mount Agassiz in the White Mountains of New Hampshire also bear his name. A crater on Mars, Crater Agassiz,[54] and a promontorium on the moon are also named in his honor. Cape Agassiz, a headland situated in Palmer Land, Antarctica, is named in his honor. A main-belt asteroid, 2267 Agassiz, is also named in association with him.

Taxa named in his honor

Biological tributes

Several animal species are named in honor of him, including

- Agassiz's dwarf cichlid Apistogramma agassizii Steindachner, 1875;

- Agassiz's perchlet, also known as Agassiz's glass fish; and the olive perchlet Ambassis agassizii Steindachner, 1866;

- The Spring Cavefish Forbesichthys agassizii (Putnam, 1872);

- the catfish Corydoras agassizii Steindachner, 1876;

- the Rio Skate Rioraja agassizii (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1841);

- The South American fish Leporinus agassizii [55]

- the Snailfish Liparis agassizii Putnam, 1874;

- a sea snail, Borsonella agassizii (Dall, 1908);

- a species of crab Eucratodes agassizii A. Milne Edwards, 1880;

- Isocapnia agassizi Ricker, 1943 (a stonefly);

- Publius agassizi (Kaup, 1871) (a passalid beetle);

- Xylocrius agassizi (LeConte, 1861) (a longhorn beetle);

- Exoprosopa agassizii Loew, 1869 (a bee fly);

- Chelonia agassizii Bocourt, 1868 (Galápagos green turtle);[56]

- Philodryas agassizii (Jan, 1863) (a South American snake);[56]

and the most well-known,

- Gopherus agassizii (Cooper, 1863) (the desert tortoise).[56]

- In 2020, a new genus of pycnodont fish (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontiformes) named Agassazilia erfoundina (Cooper and Martill, 2020) from the Moroccan Kem Kem Group was named in honor of Agassiz, who first identified the group in the 1830s.

Tribute awards

In 2005, the European Geosciences Union Division on Cryospheric Sciences established the Louis Agassiz Medal, awarded to individuals in recognition of their outstanding scientific contribution to the study of the cryosphere on Earth or elsewhere in the solar system.[57]

Agassiz took part in a monthly gathering called the Saturday Club at the Parker House, a meeting of Boston writers and intellectuals. He was therefore mentioned in a stanza of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. poem "At the Saturday Club:"

There, at the table's further end I see

In his old place our Poet's vis-à-vis,

The great PROFESSOR, strong, broad-shouldered, square,

In life's rich noontide, joyous, debonair

...

How will her realm be darkened, losing thee,

Her darling, whom we call our AGASSIZ!

Daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia Taylor

In 1850, Agassiz commissioned daguerreotypes, which were described as "haunting and voyeuristic" of the enslaved Renty Taylor and Taylor's daughter, Delia, to further his arguments about black inferiority.[58] They are the earliest known photographs of enslaved persons.[59][60][58][61] Agassiz left the images to Harvard, and they remained in the Peabody Museum's attic until 1976, when they were rediscovered by Ellie Reichlin, a former staff member.[62][63] The 15 daguerrotypes were in a case with the embossing "J. T. Zealy, Photographer, Columbia," with several handwritten labels, which helped in later identification.[63] Reichlin spent months doing research to try to identify the people in the photos, but Harvard University did not make efforts to contact the families and licensed the photos for use.[63][64]

In 2011, Tamara Lanier wrote a letter to the president of Harvard that identified herself as a direct descendant of the Taylors and asked the university to turn over the photos to her.[64][65]

In 2019, Taylor's descendants sued Harvard for the return of the images and unspecified damages.[66] The lawsuit was supported by 43 living descendants of Agassiz, who wrote in a letter of support, "For Harvard to give the daguerreotypes to Ms. Lanier and her family would begin to make amends for its use of the photos as exhibits for the white supremacist theory Agassiz espoused." Everyone must evaluate fully "his role in promoting a pseudoscientific justification for white supremacy."[59]

Aggasiz-Zealy Gallery

!["Papa" Renty Taylor Born Congo, 1775-died on/after 1866. Field hand on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Note a side profile picture can be found at online article "Louis Agassiz Two Faces"]](../I/Renty_an_African_slave.jpg.webp) "Papa" Renty Taylor Born Congo, 1775-died on/after 1866. Field hand on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Note a side profile picture can be found at online article "Louis Agassiz Two Faces"]

"Papa" Renty Taylor Born Congo, 1775-died on/after 1866. Field hand on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Note a side profile picture can be found at online article "Louis Agassiz Two Faces"]![Delia (Born America); daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]](../I/Delia1850FrontPortrait.jpg.webp) Delia (Born America); daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]

Delia (Born America); daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]![Delia daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]](../I/Slave_Portrait_Agassiz_Zealy_Woman_Side_Bust_2.jpg.webp) Delia daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]

Delia daughter of Renty on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]

![Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]](../I/JackGuineaProfileSlavePortrait.jpg.webp) Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]

Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]![Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]](../I/Jack1850FrontZealy.jpg.webp) Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]

Jack of Guinea, a slave driver on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]![Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]](../I/Drana_(frontal_portrait).jpg.webp) Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]

Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 1]![Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]](../I/Drana_(profile_view).jpg.webp) Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]

Drana daughter of Jack on B.F. Taylor Plantation, Columbia South Carolina [Picture # 2]

![Fassena a mandingo Carpender on Wade Hampton Plantation, South Carolina[Note a full face picture can be found at https://saa3dm.org/2021/11/16/1850]](../I/Slave_Portrait_Agassiz_Zealy_Man_Side_Bust_2.jpg.webp) Fassena a mandingo Carpender on Wade Hampton Plantation, South Carolina[Note a full face picture can be found at https://saa3dm.org/2021/11/16/1850]

Fassena a mandingo Carpender on Wade Hampton Plantation, South Carolina[Note a full face picture can be found at https://saa3dm.org/2021/11/16/1850]!["Jem. A Gullah..B.W. Green Plantation [See American Heritage June 1977 "Faces of Slavery"]](../I/Slave_Portrait_Agassiz_Zealy_Man_Standing_Back.jpg.webp) "Jem. A Gullah..B.W. Green Plantation [See American Heritage June 1977 "Faces of Slavery"]

"Jem. A Gullah..B.W. Green Plantation [See American Heritage June 1977 "Faces of Slavery"]

Polygenism and racism

Agassiz was a well-known natural scientist of his generation in America.[68] In addition to being a natural scientist, Agassiz wrote prolifically in the field of scientific polygenism after he came to the United States.

Upon arriving in Boston in 1846, Agassiz spent a few months acquainting himself with the northeast region of the United States.[69] He spent much of his time with Samuel George Morton, a famous American anthropologist at the time who became well known by analyzing fossils brought back by Lewis and Clark.[70] One of Morton’s personal projects involved studying cranial capacity of human skulls from around the world. Morton aimed to use craniometry to prove that white people were biologically superior to other races. His work "Crania Aegyptiaca" claimed to support the polygenism belief that the races were created separately and each had their own unique attributes.[71]

Morton relied on other scientists to send him skulls along with information about where they were acquired. Factors that can affect cranial capacity, such as body size and gender, were not taken into consideration by Morton.[70] He made questionable judgment calls such as dismissing Hindu skull calculations from his Caucasian cranial measurements because they brought the overall average down. Oppositely, he included Peruvian skull measurements alongside Native American calculations even though the Peruvian numbers lowered the average score. Despite Morton's unsound methods, his published work on cranial capacities across races was deemed authoritative in the United States and Europe. Morton is a primary influence on Agassiz's belief in polygenism.[70]

John Amory Lowell invited Agassiz to present twelve lectures in December 1846 on three subjects titled "The Plan of Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom, Ichthyology, and Comparative Embryology” as a part of the Lowell Lecture series. These lectures were widely attended with up to 5,000 people in attendance on some nights.[72] It was during these lectures that Agassiz announced for the first time that black and white people had different origins but were part of the same species.[70] Agassiz repeated this lecture 10 months later to the Charleston Literary Club but changed his original stance, claiming that black people were physiologically and anatomically a distinct species.[70]

Agassiz believed that humans did not descend from one single common ancestor. He believed that like plants and animals, various regions have differentiated species of humans.[69] He considered this hypothesis testable, and matched to the available evidence. He also indicated that there were obvious geographical barriers that were the likely cause of speciation.

Stephen Jay Gould asserted that Agassiz's observations sprang from racist bias, in particular from his revulsion on first encountering African-Americans in the United States.[73] Referencing letters written by Agassiz, Gould compares Agassiz' public display of dispassionate objectivity to his private correspondence, in which he describes "the production of half breeds" as "a sin against nature..." Describing the interbreeding of white and black people, he warns, "We have already had to struggle, in our progress, against the influence of universal equality... but how shall we eradicate the stigma of a lower race when its blood has once been allowed to flow freely into our children." In contrast, others have asserted that, despite favoring polygenism, Agassiz rejected racism and believed in a spiritualized human unity. However, in the same article, Agassiz asks the reader to consider the hierarchy of races, mentioning "The indomitable, courageous, proud Indian, — in how very different a light he stands by the side of the submissive, obsequious, imitative negro, or by the side of the tricky, cunning, and cowardly Mongolian! Are not these facts indications that the different races do not rank upon one level in nature?"

Agassiz never supported slavery and claimed his views on polygenism had nothing to do with politics.[70] His views on polygenism have been claimed to have emboldened proponents of slavery.

Accusations of racism against Agassiz have prompted the renaming of landmarks, schoolhouses, and other institutions (which abound in Massachusetts) that bear his name. Opinions about those moves are often mixed, given his extensive scientific legacy in other areas, and uncertainty about his actual racial beliefs. In 2007, the Swiss government acknowledged his "racist thinking", but declined to rename the Agassizhorn summit. In 2017, the Swiss Alpine Club declined to revoke Agassiz's status as a member of honor, which he received in 1865 for his scientific work, because the club considered that status to have lapsed on Agassiz's death. In 2020, the Stanford Department of Psychology asked for a statue of Louis Agassiz to be removed from the front façade of its building. In 2021, Chicago Public Schools announced they would remove Agassiz's name from an elementary school and rename it for the abolitionist and political activist, Harriet Tubman. In 2022, The Trustees of Reservations renamed Agassiz Rock as The Monoliths.[74]

Works

- Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1833–1843)

- History of the Freshwater Fishes of Central Europe (1839–1842)

- Études sur les glaciers (1840)

- Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (1840–1845)

- Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842–1846)

- Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (1844–1845)

- Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae (1848)

- (with A. A. Gould) Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges (Boston, 1848)

- Lake Superior: Its Physical Character, Vegetation and Animals, compared with those of other and similar regions (Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln, 1850)

- Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1857–1862)

- Geological Sketches (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866)

- A Journey in Brazil (1868)

- De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie [Essay on classification] (Trans. Felix Vogeli. Paris: Bailière, 1869)

- Geological Sketches (Second Series) (Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1876)

- Essay on Classification, by Louis Agassiz (1962, Cambridge)

Taxa described by him

- See Category:Taxa named by Louis Agassiz

See also

References

- Nicolaas A. Rupke, Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 54.

- Johnson 1906, p. 60

- Frank Leslie's new family magazine. v. 1 (1857), p. 29

- Woodward 1911, p. 367.

- Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf 2015, p. 250

- Kelly, Howard A.; Burrage, Walter L. (eds.). . . Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Company.

- Johnson 1906, p. 61

- "Agassiz's Fossil Fish". The Geological Society.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Johnson 1906, p. 62

- E.P. Evans: "The Authorship of the Glacial Theory", North American review Volume 145, Issue 368, July 1887. Accessed on January 24, 2018.

- Cameron, Dorothy (1964). Early discoverers XXII, Goethe-Discoverer of the ice age. Journal of glaciology (PDF).

- Louis Agassiz: Études sur les glaciers, Neuchâtel 1840. Digital book on Wikisource. Accessed on February 25, 2008.

- Woodward 1911, pp. 367–368.

- Woodward 1911, p. 368.

- Brice, W. R. and Silvia F. de M. Figueiroa 2001 Charles Hartt, Louis Agassiz, and the controversy over Pleistocene glaciation in Brazil. History of Science 39(2): 161-184.

- Smith, p. 52.

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- Paton, Lucy Allen. Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz; a biography. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919.

- Dupree, A. Hunter (1988). Asa Gray, American Botanist, Friend of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 152–154, 224–225. ISBN 978-0-801-83741-8.

- See, for instance, Agassiz, Louis (1851), "Contemplations of God in the Kosmos", The Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany, Vol.50, No.1, (January 1851), pp.1-17.

- Dupree, A. Hunter (1988). Asa Gray, American Botanist, Friend of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. ix–xv, 152–154, 224–225. ISBN 978-0-801-83741-8.

- Smith (1898), pp. 39–41.

- Johnson 1906, p. 63

- Smith (1898), pp. 52–66.

- Agassiz, Elizabeth Cabot Cary (1893). Louis Agassiz; his life and correspondence. MBLWHOI Library. Boston and New York, Houghton, Mifflin and company.

- A History of Cornell by Morris Bishop (1962), p. 83.

- Agassiz, Louis (1848). Bibliographia Zoologiæ Et Geologiæ. A General Catalogue of All Books, Tracts, and Memoirs on Zoology and Geology Volume 1. Ray Society.

- Agassiz, Louis (1850). Bibliographia Zoologiæ Et Geologiæ A General Catalogue of All Books, Tracts, and Memoirs On Zoology and Geology; Volume 2. Ray Society.

- Agassiz, Louis (1853). Bibliographia Zoologiæ Et Geologiæ A General Catalogue of All Books, Tracts, and Memoirs On Zoology and Geology; Volume 3. Ray Society.

- Agassiz, Louis (1854). Bibliographia Zoologiæ Et Geologiæ A General Catalogue of All Books, Tracts, and Memoirs on Zoology and Geology · Volume 4. Ray Society.

- Ermakoff, Goerge (2004). O negro na fotografia brasileira do século XIX. G. Ermakoff.

- Agassiz, Louis (1868). A Journey in Brazil. Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 9780608433790.

- "Scientific results of a Journey in Brazil: Geology and Physical Georgraphy of Brazil by Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (1807-1873) and Fred Hart - 1870".

- Freeberg, Ernest (2020). A Traitor to his Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement. New York: Basic Books. pp. 17–8, 65–6.

- Agassiz, Louis (1885). Louis Agassiz His Life and Correspondence. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 719.

- Irmscher, Christoph (2013). Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547577678.

- Museum of Fine Arts (1918). "Quincy Adams Shaw Collection". Boston, Massachusetts: Museum of Fine Arts: 2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Pauline Agassiz Shaw". bwht.org. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- Dexter, R.W. (1980). "The Annisquam Sea-side Laboratory of Alpheus Hyatt, Predecessor of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, 1880–1886". In Sears, Mary; Merriman, Daniel (eds.). Oceanography: The Past. New York: Springer. pp. 94–100. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8090-0_10. ISBN 978-1-4613-8090-0. OCLC 840282810.

- James, William. "Louis Agassiz, Words Spoken.... at the Reception of the American Society of Naturalists.... [Dec 30, 1896]. pp. 9–10. Cambridge, 1897. Quoted in Cooper 1917, pp. 61–62.

- Erlandson, David A.; et al. (1993). Doing Naturalistic Inquiry: A Guide to Methods. Sage Publications. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-8039-4938-6.; Originally published in Scudder, Samuel H. (April 4, 1874). "Look at your fish". Every Saturday. 16: 369–370.

- Shaler, Nathaniel; Shaler, Sophia Penn Page (1909). The Autobiography of Nathaniel Southgate Shaler with a Supplementary Memoir by his Wife. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 92–99.

- Cooper, Lane (1917). Louis Agassiz as a Teacher: Illustrative Extracts on his Method of Instruction. Ithaca: The Comstock Publishing Company.

- Pound, Ezra (2010). ABC of Reading. New York: New Directions. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8112-1893-1.

- Emling 2009, pp. 169–170

- Johnson 1906, p. 64

- "Peacework Back Issues | the Mismeasure of Maria Baldwin". www.peaceworkmagazine.org. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- "Committee Renames Local Agassiz School | News | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com.

- "agassiz_ns_3.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link). cambridgema.gov - Meghan E. Irons. "Hurdles Cleared, Cambridge Group Celebrates Arts Project." Boston Globe, October 1, 2009, p. B5.

- Marc Levy. "Baldwin Neighborhood Name is Approved 9-0, Replacing Agassiz; Second Such Change Since '15." Cambridge (Massachusetts) Day, August 2, 2021,

- "Agassiz". mpshistory.mpls.k12.mn.us. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2012). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 176. ISBN 978-3-642-29718-2.

- Christopher Scharpf & Kenneth J. Lazara (September 22, 2018). "Order CHARACIFORMES: Families TARUMANIIDAE, ERYTHRINIDAE, PARODONTIDAE, CYNODONTIDAE, SERRASALMIDAE, HEMIODONTIDAE, ANOSTOMIDAE and CHILODONTIDAE". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Agassiz, J.L.R.", p. 2).

- "Louis Agassiz Medal". European Geosciences Union. 2005. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- "Who Should Own Photos of Slaves? The Descendants, not Harvard, a Lawsuit Says". The New York Times. March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Moser, Erica. "Descendants of racist scientist back Norwich woman in fight over slave images". theday.com. The Day. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Browning, Kellen. "Descendants of slave, white supremacist join forces on Harvard's campus to demand school hand over 'family photos'". www.bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "The World Is Watching: Woman Suing Harvard for Photos of Enslaved Ancestors Says History Is At Stake". Democracy Now!. March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Sehgal, Parul (October 2, 2020). "The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Faces of Slavery: A Historical Find". American Heritage magazine. June 1977. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Woman who claims descent sues Harvard over refusal to return photos of enslaved man from 1850". St. Louis American. March 22, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Harvard 'Shamelessly' Profits From Photos Of Slaves, Lawsuit Claims". March 20, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Tony Marco, Ray Sanchez and (March 20, 2019). "The descendants of slaves want Harvard to stop using iconic photos of their relatives". /www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "Earthquake impacts on prestige". Stanford University and the 1906 earthquake. Stanford University. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- Smith, David C.; Borns, Harold W. (2000). "Louis Agassiz, the Great Deluge, and Early Maine Geology". Northeastern Naturalist. 7 (2): 157–177. doi:10.2307/3858648. ISSN 1092-6194. JSTOR 3858648.

- Lurie, Edward (1988). Louis Agassiz, a life in science. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3743-X. OCLC 18049437.

- Menand, Louis (2001). "Morton, Agassiz, and the Origins of Scientific Racism in the United States". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (34): 110–13. doi:10.2307/3134139. JSTOR 3134139 – via JSTOR.

- Morton, Samuel George (1849). Catalogue of skulls of man and the inferior animals : in the collection of Samuel George Morton, M.D., Penn. and Edinb. Vice President of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Author of "Crania Americana," "Crania Aegyptiaca," etc. Merrihew & Thompson, printers, No. 7 Carter's Alley. OCLC 713232597.

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305 (November 23, 2019). "Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz". Hopkins Seaside Laboratory (1892 -1917) - Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Jay., Gould, Stephen (2008). The mismeasure of man. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31425-0. OCLC 212909101.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "North Shore park drops name of 19th-century scientist who promoted racist beliefs". Boston Globe. February 28, 2022.

Sources

- Dexter, R W (1979). "The impact of evolutionary theories on the Salem group of Agassiz zoologists (Morse, Hyatt, Packard, Putnam)". Essex Institute Historical Collections. Vol. 115, no. 3. pp. 144–71. PMID 11616944.

- Emling, Shelley (2009). The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman whose Discoveries Changed the World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61156-6.

- Irmscher, Christoph (2013). Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-57767-8.

- Lurie, E (1954). "Louis Agassiz and the races of Man". Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. Vol. 45, no. 141 (published September 1954). pp. 227–42. PMID 13232804.

- Lurie, Edward (1988). Louis Agassiz: A Life in Science. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3743-2.

- Lurie, Edward (2008). "Agassiz, Jean Louis Rodolphe". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 72–74.

- Mackie, G O (1989). "Louis Agassiz and the discovery of the coelenterate nervous system". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. Vol. 11, no. 1. pp. 71–81. PMID 2573108.

- Menand, Louis (2002). "Agassiz". The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Macmillan. pp. 97–116. ISBN 978-0-374-52849-2.

- Numbers, Ronald L. (2006). The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design (Expanded ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02339-0.

- Rogers, Molly (2010). Delia's Tears: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11548-2.

- Smith, Harriet Knight, The history of the Lowell Institute, Boston: Lamson, Wolffe and Co., 1898.

- Winsor, M P (1979). "Louis Agassiz and the species question". Studies in History of Biology. Vol. 3. pp. 89–138. PMID 11610990.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Woodward, Horace Bolingbroke (1911). "Agassiz, Jean Louis Rodolphe". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 367–368.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Agassiz, Jean Louis Rudolphe". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. pp. 60–64.

Archive sources

A collection of Louis Agassiz's professional and personal life is conserved in the State Archives of Neuchâtel.

- AGASSIZ LOUIS, Fonds: Louis Agassiz (1817–1873). Archives de l'État de Neuchâtel.

External links

- Publications by and about Louis Agassiz in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Works by Louis Agassiz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Louis Agassiz at Internet Archive

- Works by Louis Agassiz at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Louis Agassiz online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang (ed.). "Agassiz, Jean (1807–1873)". ScienceWorld.

- Pictures and texts of Excursions et séjours dans les glaciers et les hautes régions des Alpes and of Nouvelles études et expériences sur les glaciers actuels by Louis Agassiz can be found in the database VIATIMAGES.

- "Geographical Distribution of Animals", by Louis Agassiz (1850)

- Runner of the Mountain Tops: The Life of Louis Agassiz, by Mabel Louise Robinson (1939) – free download at A Celebration of Women Writers – UPenn Digital Library

- Thayer Expedition to Brazil, 1865–1866 Archived September 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (Agassiz went to Brazil to find glacial boulders and to refute Darwin. Dom Pedro II gave his support for Agassiz's expedition on the Amazon River.)

- Louis Agassiz Correspondence, Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Illustrations from 'Monographies d'échinodermes vivans et fossiles'

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- Agassiz, Louis (1842) "The glacial theory and its recent progress" The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, vol. 33. p. 217–283. (Linda Hall Library)

- Agassiz, Louis (1863) Methods of study in natural history – (Linda Hall Library)

- Agassiz Rock, Edinburgh Archived January 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine – during a visit to Edinburgh in 1840, Agassiz explained the striations on this rock's surface as due to glaciation