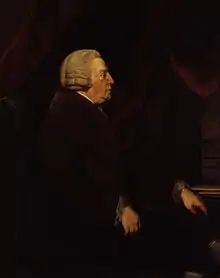

James Harris (grammarian)

James Harris, FRS (24 July 1709 – 22 December 1780) was an English politician and grammarian. He was the author of Hermes, a philosophical inquiry concerning universal grammar (1751).

Life

James Harris was born at Salisbury, Wiltshire, the son of James Harris (1674–1731) by his second marriage to Elizabeth (c. 1682–1744), daughter of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Earl of Shaftesbury.[1] He was educated at the Salisbury Cathedral School, and Wadham College, Oxford. On leaving university he was entered at Lincoln's Inn as a student of law, though he was not intended for the Bar. The death of his father in 1733 brought him an independent fortune and Malmesbury House in Salisbury's Cathedral Close.[2]

Harris became a county magistrate. He was Member of Parliament for Christchurch from 1761 until his death, and Comptroller to the Queen from 1774 to 1780. He held political office under George Grenville: in January 1763 he became a lord of the admiralty, and in April that year a lord of the treasury. He retired from his post with Grenville in 1765.[2]

Harris was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1763.[3] He died at Malmesbury House on 22 December 1780, and was buried on 28 December in Salisbury Cathedral, where there is a memorial to him in the south transept.[1]

Associations

Harris was a lover of music and a friend of Handel. He directed concerts and music festivals at Salisbury for nearly fifty years. He adapted the words for a selection from Italian and German composers (subsequently published by the cathedral organist Joseph Corfe).[4] He wrote a number of pastorals. One of them, Damon and Amaryllis was produced by David Garrick at Drury Lane, as debut piece for the singer Thomas Norris. Norris was originally a Salisbury chorister, and a protégé of Harris.[5] In 1741 John Robartes, 4th Earl of Radnor gave him the collection of Handel's music made by Elizabeth Legh (1694–1734).[6]

One correspondent of Harris was Lord Monboddo, who disclosed in a 1772 letter to him some early evolutionary thought.[7] Samuel Johnson found Harris uncongenial, saying he was "a sound, solid scholar," but "a prig" and "a coxcomb" who "did not understand his own system" in Harris's work Hermes.[2]

The music historian Charles Burney, on the other hand, esteemed him as a writer on music. Harris, his wife and daughter attended a high-powered domestic concert at Burney's house in May 1775, of which a vivid description by the 22-year-old Frances (Fanny) Burney survives: "I had the satisfaction to sit next to Mr. Harris, who is very chearful [sic] and communicative, and his conversation instructive and agreeable." His daughter Louisa ("a modest, reserved, and sensible girl") was asked to sing, and Harris accompanied her.[8]

Works

Interested in the Greek and Latin classics, Harris sought out manuscripts and printed editions that influenced his writings, as did the works of the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, his uncle.[1] Harris published in 1744 Three Treatises — on art; on music, painting and poetry; and on happiness. In 1751 appeared the work by which he became best known, Hermes, a philosophical inquiry concerning universal grammar.[4] In the direction of prescriptive grammar, it influenced Robert Lowth's English grammar of 1762.[9]

Harris also published Philosophical Arrangements and Philological Inquiries. His works were collected and published in 1801, by his son James who prefixed a brief biography.[4]

Hampshire Record Office holds Harris's papers.[10] Letters from his wife Elizabeth are also extant.[11]

Family

Harris married Elizabeth, daughter of John Clarke of Sandford, Somerset, in 1745. They had two sons and three daughters.[12] James Harris, 1st Earl of Malmesbury, the diplomat, was his elder son.[13]

References

- Dunhill, Rosemary. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12393.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 25. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Fellows details". Royal Society. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Stevenson, Kay Gilliland; Seares, Margaret; Smith, John Christopher (1998). Paradise Lost in Short: Smith, Stillingfleet, and the Transformation of Epic. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 180 note 9. ISBN 9780838637180.

- Landgraf, Annette; Vickers, David (2013). The Cambridge Handel Encyclopedia. Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-107-66640-5.

- Letter from Lord Monboddo to James Harris, 31 December 1772; reprinted by William Knight 1900 ISBN 1-85506-207-0

- The Early Diary of Frances Burney, 1768-1778, edited by Annie Raine Ellis, Vol. II, pp. 56-60 (London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., [1889] 1913).

- Webster, Merriam (1989). Webster's Dictionary of English Usage: English Dictionary. Bukupedia. p. 12. ISBN 9780877790327.

- Designation Statement on the Significance of Hampshire's Archive Collections

- Burrows, Donald; Dunhill, Rosemary; Harris, James (2002). Music and Theatre in Handel's World: The Family Papers of James Harris, 1732-1780. Oxford University Press. p. xxii. ISBN 9780198166542.

- "Harris, James (1709-80), of Salisbury, Wilts. History of Parliament Online". historyofparliamentonline.org.

- "Harris, James (1746-1820), of Salisbury, Wilts. History of Parliament Online". historyofparliamentonline.org.

Further reading

- Donald Burrows and Rosemary Dunhill, Music and Theatre in Handel's World: The Family Papers of James Harris 1732–1780, Oxford University Press, US, 2002

- Clive T. Probyn, The Sociable Humanist: The Life and Works of James Harris, 1709–1780, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991

- The Works of James Harris, Esq. 2 vols, London: F. Wingrave, 1801 (facsimile ed., Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 2003)

External links

Attribution: This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Harris, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.