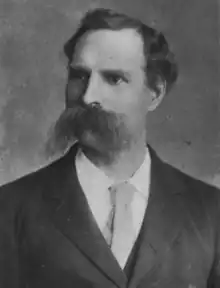

James L. Walker

James L. Walker (June 1845 – April 2, 1904), sometimes known by the pen name Tak Kak, was an American individualist anarchist of the Egoist school, born in Manchester, United Kingdom.[1]

James L. Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 1845 Manchester, United Kingdom |

| Died | 2 April 1904 (aged 58) Mexico |

| Pen name | Tak Kak |

| Occupation | Writer, philosopher, physician, publisher, journalist, educator, lawyer |

| Nationality | British-American |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Subject | Political philosophy |

| Literary movement | Egoist anarchism Individualist anarchism |

| Notable works | The Philosophy of Egoism |

Walker was one of the main contributors to Benjamin Tucker's Liberty. He worked out Egoism on his own some years before encountering the Egoist writings of Max Stirner, and was surprised with the similarities.[2] He published the first twelve chapters of Philosophy of Egoism in the May 1890 to September 1891 issues of Egoism.[3] It was first published in book form by his widow Katharine in 1905 with the assistance of Egoism editors Henry and Georgia Replogle, the former of whom contributed prefatory remarks and a biographical sketch of Walker.[4]

Walker was a physician by trade, but at varying times had also practiced law, taught at colleges, and been a newspaper publisher and editor. He spent most of his latter years residing in Mexico, having been lured to Monterrey by promises of patronage to start a Spanish-English daily newspaper there. When these promises eventually fell through, he nevertheless took it upon himself to publish a weekly English-language newspaper for several years before taking up medicine again. Intending to return to the United States after a bout with yellow fever in 1904, his travels through Mexico inadvertently brought him into contact with a local smallpox epidemic. Walker died on April 2 after being hospitalized against his will by local authorities.[5]

Thought

| Part of a series on |

| Individualism |

|---|

Walker´s philosophy is mainly put forward in his The Philosophy of Egoism. Walker's initial essays on egoism advocated egoism as a practical philosophy for how people can live their lives. However, he also believed that egoism can be reconciled with altruistic, or "other regarding" behavior. In Walker's case, egoism is the negation of "moralism."[6] Walker’s egoism "implies a rethinking of the self-other relationship, nothing less than "a complete revolution in the relations of mankind" that avoids both the "archist" principle that legitimates domination and the "moralist" notion that elevates self-renunciation to a virtue. Walker describes himself as an "egoistic anarchist" who believed in both contract and cooperation as practical principles to guide everyday interactions."[7] Walker thought that the main problems confronting human beings are all related in some way to bigotry and fanaticism, or "the determination of mankind to interfere with each others' actions...Egoism for Walker is "the "seed-bed" of a policy and habit of noninterference and tolerance. Ultimately, the egoist promotion of a laissez-faire attitude toward others supports and reinforces an anarchist social system. In its "strict and proper sense," anarchy means "no tyranny" and implies the regulation and coordination of social interaction by voluntary contract."[8]

For Walker the egoist rejects notions of duty and is indifferent to the hardships of the oppressed whose consent to their oppression enslaves not only them, but those who do not consent.[9] The egoist comes to self-consciousness, not for the God's sake, not for humanity's sake, but for his or her own sake.[10] For him "Cooperation and reciprocity are possible only among those who are unwilling to appeal to fixed patterns of justice in human relationships and instead focus on a form of reciprocity, a union of egoists, in which person each finds pleasure and fulfillment in doing things for others."[11] Walker is most interested in the relationship of the person to the social world "especially how the self navigates encounters with "groups variously cemented together by controlling ideas; such groups are families, tribes, states, and churches."[12]

Walker also established what egoism is not. First, egoism is not mere self-interest or selfishness . Second, egoists are not slaves to passion, pleasure, or immediate gratification. They are willing to postpone "immediate ends" in order to reach egoistic goals of higher value. Third, egoism cannot be reduced to greed, avarice, or purposeless accumulation. For him "The love of money within reason is conspicuously an egoistic manifestation, but when the passion gets the man, when money becomes his ideal, his god, we must class him as an altruist" because he has sacrificed his ability to assign value to the power of an external object."[13]

For Walker "what really defines egoism is not mere self-interest, pleasure, or greed; it is the sovereignty of the individual, the full expression of the subjectivity of the individual ego."[14] Walker acknowledged that "there are some involuntary reactions of the person to the environment, is based on an interactionist idea that the individual chooses, through the self, what to think and feel, and how to act, in response to internal and external stimuli. Egoism conceives the self as the "spring of action," not the content of behavior. It is the person's intent to act upon the world, rather than the infinite acquiescence to objectification."[15] Walker´s Egoism "has a political purpose and political content; it is a philosophy of individual behavior and social organization that undermines the hierarchies of groups and social institutions by stripping away the lofts ideals of the masters and revealing their egoistic motives of self-preservation and self-aggrandizement.[16]

References

- Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits, Princeton, 1988, p. 154.

- McElroy, Wendy. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books. 2003. pp. 54–55.

- McElroy, Wendy. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books. 2003. p. 55.

- James L. Walker, The Philosophy of Egoism. Katharine Walker, Denver, 1905.

- Henry Replogle, in James L. Walker's The Philosophy of Egoism. Katharine Walker, Denver, 1905, p. 69-76.

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 163

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 163

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 164

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 165

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 166

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 164

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 168

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 167

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 167

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 168

- John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Pg. 169

External links

- The Philosophy of Egoism by James L. Walker

- James L. Walker: Egoism at The Libertarian Labyrinth

- "The Question of Copyright" by Tak Kak (1891), at Fair Use Repository

- L'egoismo nelle relazioni sessuali di James L. Walker (Italian version)

- L'egoismo di James L. Walker (Italian version)

- Uccidere Cinesi di James L. Walker (Italian version)