Timeline of the John F. Kennedy assassination

This article considers the timeline of events before, during, and after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

35th President of the United States

Tenure

Appointments

Presidential campaign Assassination and legacy

|

||

Prelude

October 24, 1956: Lee Harvey Oswald drops out of high school and joins the U.S. Marine Corps, where he is trained as a sharpshooter.[1] October 31, 1959: Oswald defects to the Soviet Union and is sent to work at an electronics factory in Minsk. November 8, 1960: John F. Kennedy wins the 1960 United States presidential election. June 13, 1962: Oswald returns to the United States with his wife Marina and their child to live in Texas.[2] October 9, 1962: Oswald rents P.O. Box 2915 under his real name at the Dallas post office. He will maintain the rental until May 14, 1963.[3] November 6, 1962: Democrat John Connally is elected governor of Texas.[4] January 15, 1963: Connally takes the oath as governor of Texas.[5] As governor, he will assist with planning for President Kennedy's trip to Texas and will serve as Kennedy's host.

February 22, 1963: Ruth Paine meets the Oswalds at a party held at Everett Glover's house.[6]

March 13, 1963: Klein's Sporting Goods of Chicago receives a mail order in the amount of $21.45 ($19.95 plus $1.50 for postage and handing) for item C20-750, a World War II-surplus Italian 1891 Carcano Model 1938 rifle equipped with a 4× scope that was advertised in the February 1963 issue of American Rifleman. The name on the order slip is A. Hidell, an alias used by Oswald, and the delivery address is Oswald's Dallas post-office box.[7] The rifle sent to Oswald bears serial number C2766.[8]

March 17, 1963: Marina Oswald sends a letter to the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., asking to be granted an entrance visa to the USSR.[9]

Oswald is given notice in the latter part of March that he will be terminated from his job.

April 6, 1963: Oswald works his last day at Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall.[10]

April 10, 1963: Oswald fires a bullet that nearly misses retired general Edwin Walker, a strongly anticommunist right-wing advocate. The police determine that the shot was fired from a distance of less than 40 yards.[11] The case remained unsolved until two weeks after Oswald's death when Marina Oswald informed the FBI that it may have been her husband who had fired the shot.[12]

April 23, 1963: Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texas native, tells reporters in Dallas that President Kennedy may visit Texas sometime that summer. Johnson hopes that Kennedy's schedule would allow him to have a breakfast in Fort Worth, a luncheon in Dallas, an afternoon tea in San Antonio and dinner in Houston.[13]

April 24, 1963: In the late evening, Oswald leaves Dallas by bus for his hometown of New Orleans, seeking better employment opportunities.[14]

June 5, 1963: President Kennedy, Vice President Johnson and Governor Connally are together in a meeting in El Paso when they agree to a second presidential visit to Texas later that year.[15] (In 1978, Connally testified to the House Select Committee on Assassinations that in the spring of 1962 "Vice President Johnson told me then that President Kennedy wanted to come to Texas, he wanted to come to Texas to raise some money, have some fund-raising affairs over the state.")

June 6, 1963: Kennedy decides to embark on the Texas trip with three basic goals in mind: to raise more Democratic Party presidential campaign fund contributions,[15] to begin his quest for reelection in November 1964[16] and, because the Kennedy-Johnson ticket had barely won Texas in 1960 (and had even lost in Dallas), to mend political fences among several leading Texas Democratic Party members who appear to be fighting politically against themselves.[17]

June 24, 1963: Oswald applies for a U.S. passport in New Orleans, Louisiana, stating that he intends to depart from New Orleans during the period from October to December 1963 for proposed travel as a tourist for a duration of between three months and one year. The next day, he is issued U.S. Passport DO 92526, which will be valid for three years to all countries except Albania, Cuba and those portions of China, Korea and Vietnam that are under communist control.[18]

September 17, 1963: Jack Valenti sends an invitation to the White House asking whether President Kennedy would attend a dinner in Houston on November 21 honoring congressman Albert Thomas for his decision not to retire from Congress. The invitation is received at the White House on September 19, 1963.[19]

Lee Oswald is issued a 15-day Mexican tourist card using the name "LEE, Harvey Oswald."[20]

September 23, 1963: Ruth Paine drives Marina Oswald from New Orleans back to her home in Irving, Texas.[21] Late that night, Lee Oswald also leaves New Orleans[22] to travel to Mexico City hoping to somehow gain entrance to Cuba,[23] a country to which travel has been banned by the United States.

September 24, 1963: At a press conference in Austin, Governor Connally announces that he will visit Washington, D.C., from October 2–4, 1963 and that he hopes to see President Kennedy. Connally says that has no plans to invite Kennedy to visit Texas but would be delighted if the president would agree to a visit.[24]

The White House accepts the invitation to the Albert Thomas dinner in Houston and turns it into a two-day political trip encompassing the major cities of Texas.[25] Although Kennedy had wanted to visit Texas at some point, he had not originally planned to go there in November.[26][27]

September 25, 1963: White House sources, in an exclusive to the Dallas Morning News, announce that the president will visit Texas November 21–22, 1963 and that the tour will include Dallas.[25]

September 26, 1963: The Dallas Morning News is the first newspaper to announce the Texas visit in an article covering the president's conservation tour in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.[25]

September 27, 1963: Lee Oswald arrives in Mexico City and registers at the Hotel del Comercio.[28] He visits the Cuban consulate three times in an attempt to secure a visa to Cuba, as well as the Soviet embassy to obtain a visa, but is denied at both places.[29]

September 30, 1963: Lee Oswald purchases a bus ticket using the alias "Mr. H. O. Lee." The bus leaves Mexico City for Laredo, Texas at 8:30 a.m. on October 2.[30]

October 3, 1963: Oswald arrives in Dallas and spends the night at the YMCA.[31]

October 4, 1963: Governor Connally meets with President Kennedy at the White House.[32]

Oswald applies for a job at Padgett Printing but is not hired because of a poor recommendation provided by Robert Stovall, president of Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall.[33][34]

Oswald returns to stay at the Paines' residence in Irving for the weekend.[35]

October 11, 1963: Kenneth O'Donnell sends a reply to Jack Valenti formally accepting his invitation for the president to speak at the dinner honoring Rep. Thomas.[36]

October 15, 1963: Ruth Paine calls the Texas School Book Depository and arranges for a job interview for Oswald with building superintendent Roy Truly. Truly interviews Oswald later that day and hires him for $1.25 per hour as a temporary clerk filling customer book orders. Oswald starts work the following day.[37][38] At about the same time, Paine had separated from her husband Michael.[39]

October 20, 1963: Kenneth O'Donnell, special assistant and appointments secretary to President Kennedy, calls Jerry Bruno, the advance man for the Kennedy trips, and asks him to come to the White House to discuss the trip to Texas.[40]

October 21, 1963: Bruno meets with O'Donnell and is told to contact Walter Jenkins, one of Vice President Lyndon Johnson's top administrative assistants, to solicit his input for the trip.

October 24, 1963: Bruno meets with Jenkins, who tells Bruno about the stops that Governor Connally has suggested. The first stop would be to fly to San Antonio on November 21 and drive in a motorcade to Brooks Air Force Base, then fly to Houston and drive in a motorcade to the Rice Hotel, where the Albert Thomas dinner was originally scheduled to take place, and stay overnight at the hotel. Then on the morning of November 22, the president would fly to Fort Worth to receive an honorary degree at Texas Christian University at 9:30 a.m. and then ride in a motorcade for the short distance to Dallas,[41] where he would attend a luncheon at the annual meeting of the Dallas Citizens Council at the Statler Hilton Hotel.[42] Finally, the president would attend a fundraising dinner in Austin before returning to Washington. Jenkins suggests that Bruno visit Texas, meet with Governor Connally and evaluate the sites himself, and also meet with Democratic Texas senator Ralph Yarborough, a bitter political enemy of Connally and Johnson, to avoid any trouble between the two parties on the trip.[43]

United States ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson II delivers a contentious speech on United Nations Day at the Dallas Memorial Auditorium, where he is booed and heckled. After the speech, he is struck on the head with a picket sign and spit upon.[44] Dallas police would later fear that similar demonstrations might occur when Kennedy visited Dallas.[45] Several people, including Stevenson, warned Kennedy against coming to Dallas, but Kennedy ignored their advice.[17]

October 28, 1963: Bruno flies to Austin to begin his evaluation of the stops being considered for the Kennedy visit on November 21–22.[46][47]

October 29, 1963: Bruno meets with Henry Brown, president of the Texas AFL–CIO and a friend of Senator Ralph Yarborough, to obtain his input from labor leaders. He then has lunch with Governor Connally to review his itinerary, which includes an honorary degree from Texas Christian University; because Kennedy is Catholic, Bruno considers this event among the highlights of the trip.[48] Connally informs Bruno that he has assigned different members of his staff to each stop on the itinerary and that they would be in charge of the visit.[49] Bruno tells Connally that he welcomes his input and suggestions, but that the final decisions on the itinerary will be made by the White House.[50][51]

Governor Connally announces that a "Texas welcome dinner" for Kennedy will be held in Austin on November 22. The governor says that the dinner will be a $100-per-plate event held at 7:30 p.m. at the Austin Municipal Auditorium as a climax to the president's Texas trip. It is sponsored by the state Democratic executive committee. No other plans have been completed except those for the November 21 Albert Thomas appreciation dinner in Houston.[52]

October 30, 1963: Bruno and Johnson aide Clifton Carter visit the Texas cities that the president will visit.[53] The San Antonio and Houston sites are checked and confirmed as acceptable, but when visiting Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, Bruno is informed by school officials that the university does not intend to confer an honorary degree to the president and that they have only approved the use of their campus as the location for a speech. Bruno informs Connally of this development, and Connally says that he will meet with the university's board of regents the next night.[41] Bruno travels to Dallas to evaluate the ballroom at the Statler Hilton Hotel where the luncheon is planned to take place on November 22. He is met there by J. Erik Jonsson, chairman of the Dallas Citizens Council (and an owner of Texas Instruments) and Robert B. Cullum, chairman of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce and owner of the Tom Thumb Food Stores. Cullum informs Bruno that the ballroom at the Statler Hilton is now unavailable because organizers of a bottlers' convention had reserved it and would not surrender it.[54] Jonsson and Cullum suggest the Dallas Trade Mart, but after visiting the site, Bruno dislikes the many catwalks that would be above the president, which, in light of the Stevenson incident that had just occurred a few days earlier, could present a security problem. He asks to be shown other available sites in Dallas.[55]

October 31, 1963: Bruno visits two other potential luncheon sites, the Dallas Memorial Auditorium, which he deems too large, and the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest, which he believes would be too far out of town and thus impractical. He is also informed that Governor Connally is unhappy with the decision not to use the Trade Mart for the luncheon because of the catwalk issue. Bruno agrees to visit the Trade Mart again but retains his misgivings. Connally telephones that he has met with the TCU board of regents and that they will not confer an honorary degree on the president.[56] Bruno is now faced with two holes in the schedule, Fort Worth and Dallas. One last place is suggested as a luncheon possibility, the Women's Building (now known as the Women's Museum) at the fairgrounds at Fair Park.[57]

President Kennedy is asked at a press conference about rumors that Johnson will not be selected as his running mate in the 1964 election,[58][59] which Kennedy denies.[60]

November 1, 1963: Bruno returns to Washington, D.C., with the Dallas luncheon site location still undecided. The Fort Worth visit is eventually resolved when the city's chamber of commerce agrees to sponsor a breakfast for the president. Because of this, the president's overnight stay is changed from Houston to Fort Worth so that he will have time to attend the breakfast.[61][62]

November 4, 1963: Gerald Behn, the Secret Service Special Agent in Charge (SAIC) for the White House detail,[63] telephones Forrest Sorrels, Secret Service SAIC of the Dallas district. He instructs Sorrels to survey the buildings that the president is planning to visit during the Dallas leg of the trip. The two leading contenders to host the Dallas luncheon are the Trade Mart (strongly favored by Governor Connally) and the Women's Building at the state fairgrounds, which Bruno favors and Connally bitterly opposes.[64] Later that day, Sorrels reports back to Behn that the Women's Building appears to be preferable from a security standpoint, but that it is not a suitable place to take the president. He reports that the Trade Mart has about 60 entrances as well as six catwalks over the area where the luncheon would be held, which could pose a problem in adequately staffing the site with security personnel.[65]

White House Secret Service agent Winston Lawson is informed that he has been assigned to the Dallas visit.[66]

November 5, 1963: Bruno visits the White House and has separate meetings with Kenneth O'Donnell, Gerald Behn and Walter Jenkins. It is decided that the Trade Mart poses too great a security risk, and the Women's Building is chosen as the Dallas luncheon site.[67]

November 6, 1963: White House press secretary Pierre Salinger announces that First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy will accompany the president on his Texas trip.[68]

November 7, 1963: The Albert Thomas appreciation dinner to be held on November 21 sells out a second time. Organizers of the dinner had already moved the venue from the Rice Hotel, where the event had sold out, to the larger Sam Houston Coliseum because of increased demand for tickets once it became known that Kennedy would attend. After it was announced that the First Lady would also attend, tickets to the dinner at the larger venue sold out as well.[69]

Bruno composes a proposed schedule for the Texas trip, which includes the Women's Building as the site for the Dallas luncheon.[70][71]

November 8, 1963: It is announced that First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy will begin resuming her official White House duties on November 20, more than a month earlier than expected. She had previously announced the cancellation of all her events for the rest of the year following the premature birth and death of her third child, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, the past August.[72]

November 9, 1963: Oswald is driven by Ruth Paine to take his driver's license permit test, but because there is a special election that day, the office is closed.[73][74]

Around 2 p.m., Oswald test-drives a new red Mercury Comet Caliente two-door hardtop at a dealership at 118 East Commerce in Dallas. He tells salesman Albert Bogard that he will be back to buy it in two or three weeks when he will have the $300 down payment.[75][76]

November 12, 1963: A special flight carrying all the advance groups that are to work on the preparation for the trip to Houston, San Antonio, Austin, Fort Worth and Dallas departs Andrews Air Force Base at 8:20 a.m.[77]

November 13, 1963: Jack Puterbaugh and White House Secret Service agent Winston Lawson, along with Dallas Secret Service agents Forrest Sorrels and Robert Steuart, visit the office of Robert B. Cullum, president of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce, to discuss plans for the Kennedy visit. They reexamine the Trade Mart and the Women's Building and meet with representatives of the Trade Mart.[78]

November 14, 1963: Acquiescing to the wishes of Governor Connally, Kenneth O'Donnell reverses his prior decision to hold the Dallas luncheon at the Women's Building and changes the location to the Dallas Trade Mart. According to both O'Donnell and Bruno, this change in the luncheon site, although seemingly insignificant at the time, dramatically alters the motorcade route taken through Dallas.[79][80][81]

Lee Oswald appears at the Allright Parking Garage at 1208 Commerce Street to inquire about job openings.[82]

November 15, 1963: President Kennedy delivers a speech in New York City at the AFL–CIO convention and then flies to West Palm Beach, Florida to spend his last weekend.[83]

The White House announces that the Dallas Trade Mart will be the site of President Kennedy's luncheon address and that a motorcade will proceed through downtown Dallas. Until that point, there had been speculation in the news media that Kennedy's tight schedule in Texas would not allow enough time for a motorcade through Dallas.[84][85]

November 16, 1963: Dallas civic leaders issue statements urging against demonstrations or incidents that may occur during President Kennedy's visit. Dallas County judge W. L. Sterrett says: "I am hoping we won't have any kind of demonstration here. I have confidence that there won't be anything of that sort. That kind of thing can give a city and county a black eye."[86]

November 18, 1963: Kennedy confides to his good friend senator George Smathers of Florida that Vice President Johnson wants First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy to ride in the car with him during the upcoming tour of Texas.[87] The exact motorcade route is finalized.

Dallas police chief Jesse Curry increased the level of security during Kennedy's visit; he put into effect the most stringent security precautions in the city's history.[45] Curry even deputized citizens to take action for any suspicious acts that could endanger the president.[88]

November 19, 1963: The White House formally announces the timetable of events for the president's visit, including a planned arrival time of 12:30 p.m. CST at the Trade Mart.[89]

November 21, 1963: At 11:07 p.m., Air Force One lands at Carswell Air Force Base on the outskirts of Fort Worth, Texas. The president and his wife are met by Raymond Buck, president of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, and his wife. Air Force Two also lands at Carswell with the vice president Lyndon Johnson, Texas governor John Connally and Senator Ralph Yarborough. Connally and Yarborough dislike each other so much Yarborough is unwilling to travel in the same car with Johnson, who is an ally of Connally. The following day, the president instructs him to ride with Johnson.[90]

At 11:35 p.m., the Kennedys arrive at the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth, after being cheered by well-wishers lined on the route toward the West Freeway. The president and Mrs. Kennedy shake hands with admirers gathered outside the hotel before retiring to their assigned suite (Room 850) for the night.

November 22

All times CST unless otherwise stated.

8:45 a.m. The president speaks before breakfast in a square across Eighth Street. Kennedy praises Fort Worth's aviation industry. The attendees, members of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, are largely conservative Republicans.[91]

9:10 a.m. Kennedy takes his place in the Hotel Texas' grand ballroom for a scheduled speech. After the speech, presidential adviser Kenny O'Donnell informs Roy Kellerman, the Secret Service agent in charge of the trip, that the presidential limousine should not be equipped with its bubbletop if the weather is clear in Dallas.[90] Later, assistant (now-ranking), press secretary Malcolm Kilduff shows the Kennedys a negative advertisement published in The Dallas Morning News with the headline "Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas." Kennedy tells his wife: "We're heading into nut country today."

10:40 a.m.: Kennedy's motorcade departs Hotel Texas for Carswell Air Force Base.[92]

11:20 a.m.: Air Force One departs Carswell Air Force Base for Dallas, Texas.[92]

11:35 a.m.: Air Force Two arrives at Love Field in Dallas.[92][93]

11:38 a.m.: Air Force One arrives at Love Field in Dallas.[92][93]

11:44 a.m.: The Kennedys and Connallys disembark Air Force One and are greeted by the Johnsons.[92] The motorcade cars had been lined up in order earlier that morning. The plan is for the motorcade to proceed from Love Field through downtown Dallas before arriving at the Trade Mart at 12:15 p.m., where Kennedy is scheduled to deliver a speech and share a steak luncheon with local government, business, religious and civic leaders and their spouses. Invitations for the event specify a noon start time.

Dallas/Fort Worth's television stations were each assigned separate details. As Bob Walker of WFAA-TV was providing live coverage of the president's arrival at Love Field, KRLD-TV's Eddie Barker was set to broadcast from the Trade Mart for Kennedy's luncheon speech. KTVT had originated live coverage of the breakfast speech in Fort Worth earlier in the day. On hand to report the arrival on radio is Joe Long of KLIF-AM.

11:55 a.m.: The motorcade leaves Love Field for its 10-mile trip through downtown Dallas.[93] The motorcade does not depart Love Field until about 15 minutes after the party had arrived there, as the president and his wife take time to shake hands with many of the enthusiastic supporters.

12:30 p.m.: Shots are fired as the motorcade passes the Texas School Book Depository.[93]

12:34 p.m.: The first United Press International bulletin clears the wire stating: "Three shots were fired today at the president's motorcade in downtown Dallas."[93]

12:36 p.m.: President Kennedy's limousine arrives at Parkland Memorial Hospital.[93]

12:40 p.m.: Viewers of the live soap opera As The World Turns receive the first national television report of the shooting from CBS News anchorman, Walter Cronkite.[93]

12:45 p.m.: Dan Rather of CBS calls Parkland Memorial Hospital; a doctor there tells him he believes Kennedy is dead.[93]

12:50 p.m.: Kennedy's top military aide General Godfrey McHugh calls Air Force One from Parkland to state that they will soon be leaving for Andrews Air Force Base.[94]

1:00 p.m.: President Kennedy is officially pronounced dead.[93]

1:16 p.m.: The first report that Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit has been shot.[93]

1:26 p.m.: Lyndon Johnson departs Parkland Memorial Hospital for Love Field.[93]

1:30 p.m.: Johnson, protected by Rufus Youngblood in a car driven by Jesse Curry, along with passengers Congressmen Albert Thomas and Homer Thornberry, arrives at Air Force One.[94] Lady Bird Johnson, Congressman Jack Brooks, and three members of the Secret Service also arrive in a second car, and Jack Valenti, Lem Johns, Cliff Carter, and Cecil Stoughton arrive in a third.[94] They are followed by additional cars containing officials and aides for both Kennedy and Johnson.[94]

1:33 p.m.: White House Assistant Press Secretary Malcolm Kilduff announces at Parkland Memorial Hospital that Kennedy is dead.[93][94]

1:38 p.m.: Anchorman Cronkite reports the official word that President Kennedy is dead and Johnson will be sworn in as the United States' 36th President.[93][94]

1:40 p.m.: Johnson telephones Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to express his condolences and ask where he should take the oath of office of the president of the United States.[94]

1:50 p.m.: Johnson telephones his friend Irving Goldberg, an attorney.[94] The two decide to ask Sarah T. Hughes to administer the oath.[94]

1:51 p.m.: Lee Harvey Oswald is arrested at the Texas Theater in Dallas.[93]

2:10 p.m.: Abraham Zapruder arrives at WFAA-TV in Dallas and is interviewed about his film of the assassination.[93]

2:13 p.m.: Police find the weapon used to kill the president on the 6th floor of the Texas School Book depository.[93]

2:38 p.m.: Johnson is sworn in as president by federal judge Sarah Hughes on Air Force One.[93]

2:46 p.m.: Air Force One departs Love Field for Washington, D.C.[93]

Motorcade vehicles and personnel

The presidential motorcade consisted of the following vehicles and occupants, in the order in which the vehicles appeared:[95]

- The lead car, an unmarked white four-door Ford Mercury sedan:

- Dallas police chief Jesse Curry (driver)

- Secret Service SA advance agent Winston Lawson (right front)

- Dallas County sheriff Bill Decker (left rear)

- Secret Service SAIC agent Forrest Sorrels (right rear)

- Presidential limousine, a midnight blue four-door 1961 Lincoln Continental Convertible (modified) (SS-100-X):

- Secret Service driver agent William Greer (driver)

- Secret Service ASAIC Roy Kellerman, in charge of the White House detail for the Texas trip (right front)

- Nellie Connally (left middle)

- Texas governor John Connally (right middle)

- First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (left rear)

- President John F. Kennedy (right rear)

- Motorcycle escorts for the presidential limousine:

- Dallas police officer Billy Joe Martin (left)

- Dallas police officer Robert W. "Bobby" Hargis (left)

- Dallas police officer James M. Chaney (right)

- Dallas police officer Douglas L. Jackson (right)

- Secret Service follow-up car, a black four-door 1956 Cadillac Touring convertible (SS-679-X) code-named "Halfback":[96]

- Secret Service driver agent Sam Kinney (driver)

- Secret Service ATSAIC Emory Roberts (right front)

- Secret Service SA Clint Hill, in charge of the First Lady's security (left front running board)

- Secret Service SA William T. McIntyre (left rear running board)

- Secret Service SA Jack Ready (right front running board)

- Secret Service SA Paul Landis (right rear running board)

- Presidential aide Kenneth O'Donnell (left middle)

- Presidential aide David Powers (right middle)

- Secret Service driver agent George Hickey (left rear)

- Secret Service SA Glen Bennett (right rear)

- Vice President's car, a steel grey four-door 1964 Lincoln convertible:

- Texas state policeman Hurchel Jacks (driver)

- Secret Service ASAIC Rufus Youngblood (front passenger)

- United States Senator Ralph Yarborough (left rear)

- Second Lady Lady Bird Johnson (middle rear)

- Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson (right rear)

- Vice Presidential Secret Service follow-up car, a yellow four-door 1964 Ford Mercury sedan, model 54A Monterey with Breezeway design hardtop, code-named "Varsity":

- Texas state policeman Joe Henry Rich (driver)

- Vice-presidential aide Cliff Carter (front middle)

- Secret Service SA Jerry Kivett (right front)

- Secret Service SA Woody Taylor (left rear)

- Secret Service ATSAIC Lem Johns (right rear)

- Mayor's car, a white two-door 1964 Ford Mercury Comet Caliente convertible, model 76B with red interior:

- Texas state policeman Milton T. Wright (driver)

- Dallas mayor Earle Cabell (front right)

- Elizabeth "Dearie" Cabell, the mayor's wife (left rear)

- Texas congressman Ray Roberts (right rear)

- National press-pool car, a grey/blue two-door 1960 Chevrolet Bel Air sedan hardtop (on loan from Southwestern Bell):[97][98]

- Telephone company employee (driver)

- Malcolm Kilduff, White House assistant press secretary (right front); for this trip, Kilduff was substituting for Pierre Salinger, who was traveling to Japan with several cabinet officers, including Secretary of State Dean Rusk.[99][100][101]

- Merriman Smith, UPI (middle front)[97]

- Robert Baskin, The Dallas Morning News (left rear)

- Jack Bell, Associated Press (middle rear)[102][103]

- Bob Clark, ABC (right rear)

- Camera car #1, national motion-picture cameras, a yellow two-door 1964 Chevrolet Impala Super Sport (SS) convertible:

- Texas state policeman Harlan E. Veasey (driver)

- John Hofan, NBC sound technician (middle front)

- Dave Wiegman, Jr., NBC cameraman (right front)

- Thomas J. Craven, CBS cameraman (left rear)

- Cleveland Ryan, lighting technician (middle rear)

- Thomas "Ollie" Atkins, U.S. Navy, White House filmographer (right rear)

- Camera car #2, national still cameras, a silver two-door 1964 Chevrolet Impala convertible:

- Driver

- Clint Grant, Dallas Morning News photographer (right front)

- Frank Cancellare, UPI photographer (middle right)

- Cecil Stoughton, White House Communications Agency, White House photographer (left rear)

- Arthur B. Rickerby, Life photographer (middle rear)

- Henry Burroughs, Associated Press photographer (right rear)

- Camera car #3, local cameras, a grey two-door 1964 Chevrolet Impala convertible:

- Department of Public Safety employee (driver)

- James H. Underwood, assistant news director for KRLD-TV and KRLD radio, with motion-picture camera (middle front)

- Thomas C. Dillard, Dallas Morning News photographer (right front)

- James Darnell, WBAP-TV, with motion-picture camera (left rear)

- Malcolm O. Couch, WFAA-TV, with motion-picture camera (middle rear)

- Bob Jackson, Dallas Times Herald photographer (right rear)

- Congressmen's car #1, a white two-door 1964 Ford Mercury Comet Caliente convertible, model 76B with red top:

- Driver

- Congressman George H. Mahon, Lubbock, Texas (right front)

- Congressman Walter E. Rogers, Pampa, Texas (left rear)

- Congressman Homer Thornberry, Austin, Texas (middle rear)

- Larry O'Brien, special assistant to the president (right rear)

- Congressmen's car #2, a white two-door Ford Mercury Comet Caliente, model 76D convertible:

- Driver

- Congressman Albert Thomas, Houston, Texas (middle front)

- Congressman Jack Brooks, Beaumont, Texas (right front)

- Congressman Lindley Beckworth, Gladewater, Texas (left rear)

- Congressman Olin E. Teague, College Station, Texas (middle rear)

- Congressman Jim Wright, Fort Worth, Texas (right rear)

- Congressmen's car #3, a grey 1964 Lincoln sedan:

- Driver

- Congressman John Young, Corpus Christi, Texas (right front)

- Congressman Henry B. Gonzalez, San Antonio, Texas (left rear)

- State senator William Neff Patman (middle rear)

- Congressman Graham Purcell (right rear)

- VIP car, a four-door, nine-passenger 1964 Ford Colony Park Station Wagon, model 71D:

- Maj. General Ted Clifton, U.S. Army, presidential military aide (driver)

- Maj. General Godfrey McHugh, U.S. Air Force, presidential military aide (right front)

- Julian Reed, Gov. Connally's press secretary (left rear)

- Two Continental Trailways press buses, a local press car (four-door Chevrolet hardtop), a Western Union car (black 1957 Ford hardtop), the White House Signal Corps car (a white four-door 1964 Chevrolet Impala Sedan hardtop carrying warrant officer Ira Gearhart, who carried the Presidential Emergency Satchel, also known as the "nuclear football"), the official party bus (Continental Trailways bus) carrying Evelyn Lincoln, the president's personal secretary and rear admiral George G. Burkley, the president's physician), several extra cars and police escorts.

- Abbreviations used above include:

- SA: Secret Service Special Agent

- SAIC: Special Agent in Charge

- ASAIC: Assistant Special Agent in Charge

- ATSAIC: Assistant to the Special Agent in Charge

Secret Service driver agents operated through their own command chain. Driver agents were typically recruited from the uniformed White House Police Force.[104]

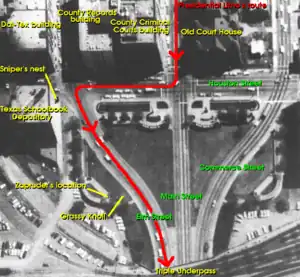

Presidential motorcade route

The motorcade route took a left turn from the south end of Love Field to West Mockingbird Lane and continued through to central Dallas. It progressed down Main Street, then at 12:29 p.m. CST turned right (westbound) into Houston Street, fatefully entering Dealey Plaza. The presidential motorcade began its route without incident, stopping twice so that President Kennedy could shake hands with Catholic nuns and schoolchildren. This exact route cannot be driven today as several of the roads have changed.

The motorcade approached the Texas School Book Depository, and then made a sharp 135 degree left turn onto Elm Street, a downward-sloping road that extends through the plaza and under a railroad bridge at a location known as the "triple underpass." The giant Hertz Rent-a-Car clock on top of the Schoolbook Depository building was seen to change from 12:29 to 12:30 as the limousine turned into Elm Street.[105]

Most of the witnesses recalled that the first shot was fired after the president had started waving with his right hand. Several onlookers recalled hearing three shots, with the second and third shots bunched distinctly much closer together than were the first and second shots. Witness testimony varies; some heard only two shots but others claimed to have heard as many as eight. The Zapruder film shows the president reemerging after being temporarily hidden from view by the Stemmons Freeway sign at Zapruder film frames 215 to 223, and his mouth has already opened wide in an anguished expression by frame 225. He has already been impacted by a bullet that struck him in the throat, and another in his mid-back, a shallow wound, with his hands clench into fists. He then quickly raises his fists dramatically in front of his face and throat as he turns to the left toward his wife. Secret Service Agent Clint Hill testified that he heard one shot, then jumped off the running board of the Secret Service follow-up car directly behind Kennedy (Hill was filmed jumping off his follow-up car at the equivalent of Zapruder frame 308; about a quarter of a second before the president's head exploded at frame 313). Hill then rapidly ran towards the Presidential limo.

As the limousine began speeding up, Mrs. Kennedy was heard to scream[106] and she climbed out of the back seat onto the rear of the limo. At the same time, Hill managed to climb aboard and hang onto the suddenly accelerating limo, and Mrs. Kennedy returned to the back seat. Hill then shielded her and the President. Both of the Connallys stated they heard Mrs. Kennedy say, "I have his brains in my hand!" The limo driver and police motorcycles turned on their sirens and raced at high speeds to Parkland Hospital, passing their intended destination of the Dallas Trade Mart along the way, and arriving at about 12:38 p.m. (CST).

Governor Connally was also struck by the shots, and his wife pulled him closer to her. He suffered several severe wounds that he survived; a bullet entry wound in his upper right back located just behind his right armpit; four inches of his right, fifth chest rib was pulverised; a two-and-a-half inch sized chest exit wound; his right arm's wrist bone was fractured into seven pieces; and he had a bullet entry wound in his left inner thigh. Although there is controversy about exactly when he was wounded, analysts from both the Warren Commission (1964) and House Select Committee on Assassinations (1979) believed that his wounds had been inflicted nearly simultaneously with President Kennedy's in their theories that the two men were struck by a single bullet. The Commission theorized both men were hit nearly simultaneously between Zapruder film frames 210 to 225, while the Committee theorized it happened at frame 190.

Witness James Tague was also injured by the shots when he received a superficial face wound. The Main Street south curb he had been standing 23.5 feet away from was struck by a bullet or bullet fragment that had no copper sheath, and a fragment of the concrete curb or a bullet fragment struck Tague on his right cheek. At Zapruder frame 313 Tague's head top was located 271 feet away from and 16.4 feet below President Kennedy's head top and the limousine's front windshield and its pushed nearly vertically straight-upwards sun visors were in between the president and the impacted curb point. The bullet or bullet fragment that struck the concrete curb was never found.

The Warren Commission report states that seconds after the shooting Roy Kellerman consulted his watch and said "12:30" to William Greer, before he radioed to Police Chief Jesse Curry that the President had been shot. Curry then communicated an order for Parkland Hospital to stand by - the Dallas police radio log reflects that this communication was made at 12:30.[107]

Immediate aftermath

Lee Harvey Oswald

Oswald was confronted by Dallas patrolman Marion L. Baker and Texas School Book Depository superintendent Roy Truly in the second-floor lunchroom. Baker let Oswald pass after Truly identified Oswald as an employee.[108][109][110] Oswald was next seen by a secretary as he crossed through the second-floor business office carrying a soda bottle.[111] He left the building through its front door at approximately 12:33 p.m.[112] Initially, Truly and Occhus Campbell, the Texas School Book Depository's vice president, said that they had seen Oswald in the first-floor storage room. When asked during his interrogations about his whereabouts, Oswald claimed that he "went outside to watch P. Parade"(referring to the presidential motorcade), was "out with [William Shelley, a foreman at the depository] in front"[113] and that he was at the "front entrance to the first floor" when he encountered a policeman.[114]

Estimates of when the depository building was sealed off by police range from 12:33 to 12:50 p.m.[115] The streets in and around Dealey Plaza were not immediately closed, and photographs taken just nine minutes after the assassination show that vehicles were still driving on Elm Street in front of the Texas School Book Depository.

After leaving the depository, Oswald walked seven blocks before boarding a bus. When the bus became ensnarled in traffic, he exited the bus, walked to a nearby bus station, and hired a taxi. He asked the cab driver to stop several blocks past his rooming house at 1026 North Beckley Ave., and he then walked back to the house. He arrived there at around 1:00 p.m. According to housekeeper Earlene Roberts, he departed three or four minutes later. She last saw him standing at a bus stop outside the rooming house.[116]

At 1:15 p.m., Oswald shot and killed Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit near the intersection of 10th St. and Patton Ave.,[117][118][119] 0.86 miles from the rooming house. Thirteen people witnessed Oswald shooting Tippit or fleeing the immediate scene.[120][121] By that evening, five of the witnesses had identified Oswald in police lineups, and a sixth identified him the following day. Four others subsequently identified Oswald from a photograph.[120][121]

After killing Tippit, Oswald was seen traveling on foot toward the Texas Theatre on West Jefferson Blvd.[122] At about 1:35 p.m. Johnny Calvin Brewer, the manager of Hardy's Shoe Store, saw Oswald turning his face away from the street and ducking into the entranceway of Brewer's store as Dallas police cars approached with sirens audible.[123] When Oswald left the store, Brewer followed him and watched him enter the Texas Theatre without paying while ticket attendant Julie Postal was distracted.[123] Brewer notified Postal, who in turn informed the Dallas police at 1:40 p.m.[123]

Almost two dozen policemen, sheriffs and detectives in several patrol cars arrived at the theater.[123] When an arrest attempt was made at 1:50 p.m. inside the theater, which was showing the 1961 film War Is Hell, Oswald resisted arrest and punched and attempted to shoot a patrolman after yelling, "Well, it's all over now!"[123][124]

President Kennedy

Immediately after the assassination, the motorcade sped to Parkland Hospital along Stemmons Freeway and Harry Hines Boulevard, approximately four miles away. The limousine, speeding at an estimated 80 miles per hour (130 km/h), arrived at the emergency entrance at about 12:35 p.m.[125]

Parkland Hospital admitted Kennedy and Connally and immediately began medical treatment. Malcolm Perry, assistant professor of surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and a vascular surgeon on the Parkland staff, was the first to treat Kennedy. Perry performed a tracheotomy followed by cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed with another surgeon.[125][126] Other doctors and surgeons worked frantically to save the president's life, but the wounds were too severe.[127]

Father Oscar Huber, a Catholic priest, was summoned to the hospital to perform the sacramental last rites for Kennedy.[128][129]

At 1:00 p.m. CST, Kennedy was pronounced dead after all vital activity had ceased.[130][129] Those who had treated Kennedy observed that the president's condition was "moribund,"[131] meaning that he had no chance of survival upon arrival at the hospital. "We never had any hope of saving his life," Perry said.[124][132] "I am absolutely sure he never knew what hit him," said Tom Shires, Parkland's chief of surgery.[133][134] Father Huber, after administering the last rites to the president, told The New York Times that the president was already dead upon the priest's arrival at the hospital.[135][124] Huber had needed to temporarily remove a sheet covering Kennedy's face so that the last rites could be performed.[135][136] Governor Connally was soon taken to emergency surgery, where he underwent two operations that day.

After receiving word of the president's death, acting White House press secretary Malcolm Kilduff entered the hospital room where new president Johnson and his wife were sitting.[102][137] Kilduff approached them and said, "Mr. President, I have to announce the death of President Kennedy. Is it OK with you that the announcement be made now?"[137] Johnson ordered that the announcement be made only after he left the hospital.[137] When asking that the announcement be delayed, Johnson told Kilduff: "I think I had better get out of here.. .before you announce it. We don't know whether this is a worldwide conspiracy, whether they are after me as well as they were after President Kennedy, or whether they are after Speaker [John W.]McCormack or Senator [Carl] Hayden. We just don't know."[102][101] He later recounted to Merle Miller: "I asked that the announcement be made after we had left the room...so that if it were an international conspiracy and they were out to destroy our form of government and the leaders in that government, that we would minimize the opportunity for doing so."[138]

At 1:33 p.m. CST, Kilduff entered a nurses' classroom at the hospital filled with press reporters and delivered the official announcement:[129][127]

President John F. Kennedy died at approximately 1:00 CST today, here in Dallas. He died of a gunshot wound to the brain. I have no other details regarding the assassination of the president.[137][139]

Shortly after 2:00 p.m. CST, Kennedy's body was removed from Parkland Hospital and driven to Air Force One at Love Field.[140] The removal occurred after an angry confrontation between Kennedy's special assistant Ken O'Donnell (backed by Kennedy's Secret Service agents) and doctors including medical examiner Earl Rose, along with a justice of the peace. The removal of President Kennedy's body may have been illegal according to Texas state law because it occurred before a forensic examination could be performed by the Dallas coroner.[141]

Breaking the news

Locally in Dallas

In Dallas, The Rex Jones Show on music station KLIF was interrupted by the first news bulletin at approximately 12:38 p.m. CST.[142] A "bulletin alert" sounder faded in during the song "I Have a Boyfriend" by the Chiffons. The song was stopped and newscaster Gary DeLaune made the first announcement over the bulletin signal:

This KLIF bulletin from Dallas: Three shots reportedly were fired at the motorcade of President Kennedy today near the downtown section. KLIF News is checking out the report. We will have further reports. Stay tuned.

KBOX reporter Sam Pate, who was on the Stemmons Freeway in a mobile news cruiser at the time of the shooting, covered the scene at Dealey Plaza and at Dallas City Hall with live radio updates. However, the widely repeated audio clip of Pate breathlessly reporting "It appears as though something has happened in the motorcade route!" is in fact taken from a reenactment recorded several days later.[143][144][145]

Dallas CBS Radio affiliate KRLD concluded the coverage of the presidential party's arrival at Love Field and switched to reporter Bob Huffaker, who was standing at the corner of Main and Akard Streets in the downtown area, just 1/2 mile east of Dealey Plaza. After the president's car passed him, Huffaker continued reporting for several more minutes and was believed to have been on the air as the shooting took place (although shots cannot be heard in the audio coverage). Shortly after KRLD returned to regular programming with the nationally syndicated religious program Back to the Bible, the first reports of the shooting came through CBS Radio. Huffaker was not aware of the developments until he arrived back at the KRLD studio after wrapping up his coverage, and he quickly drove to Parkland Hospital to report the scene outside the emergency entrance.

NBC Radio affiliate WBAP played instrumental music, with interruptions for local bulletins, until NBC Radio's continuous coverage began.

Dallas' ABC television affiliate WFAA was airing a local lifestyle program, The Julie Benell Show. At 12:45 p.m. CST, the station abruptly switched from the prerecorded program to news director Jay Watson, who had been at Dealey Plaza and had heard three shots before running back to the station:

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. You'll excuse the fact that I am out of breath, but about 10 or 15 minutes ago, a tragic thing, from all indications at this point, has happened in the city of Dallas. Let me quote to you this... [briefly looks down at the bulletin sheet in his left hand] And I'll -- you'll excuse me if I am out of breath. A bulletin, this is from the United Press from Dallas: (Reading UPI bulletin) 'President Kennedy and Governor John Connally have been cut down by assassins' bullets in downtown Dallas. They were riding in an open automobile when the shots were fired. The president, his limp body carried in the arms of his wife Jacqueline, has rushed to Parkland Hospital.'[146]

Watson then anchored WFAA's continuous coverage of the tragedy with Jerry Haynes, host of the children's show Mr. Peppermint, including an interview with witnesses Abraham Zapruder and Bill and Gayle Newman.

NBC affiliate WBAP was showing a program called Dateline at the time when the news first broke.[147]

Nationally

The first national news bulletin of the shooting was transmitted over the ABC Radio Network at 12:36 p.m. CST/1:36 p.m. EST.[148] The network was airing the Music in the Afternoon program hosted by Dirk Fredericks and Joel Crager,[149][150] and Doris Day's recording of "Hooray for Hollywood" was playing when newscaster Don Gardiner interrupted with:

We interrupt this program to bring you a special bulletin from ABC Radio. Here is a special bulletin from Dallas, Texas. Three shots were fired at President Kennedy's motorcade today in downtown Dallas, Texas.[151] This is ABC Radio. To repeat, in Dallas, Texas, three shots were fired at President Kennedy's motorcade today, the president now making a two-day speaking tour of Texas. We're going to stand by for more details on the incident in Dallas. Stay tuned to your ABC station for further details. Now we return you to your regular program.[148]

At 12:40 p.m. CST/1:40 p.m., CBS became the first television network to report the news, interrupting its live broadcast of the soap opera As the World Turns. A large, black "CBS News Bulletin" slide appeared on-screen while Walter Cronkite, reporting from the CBS Radio flash booth, filed an audio-only report. Cronkite could not immediately appear on the air because there were no active and ready cameras in the CBS newsroom; television cameras of the era used image orthicon tubes that required approximately 20 minutes of warmup time (CBS would, shortly after this, enact a policy that ensured a camera would be operational at all times for breaking news bulletins).[152] Cronkite announced:

Here is a bulletin from CBS News. In Dallas, Texas, three shots were fired at President Kennedy's motorcade in downtown Dallas. The first reports say that President Kennedy has been seriously wounded by this shooting. More details just arrived. These details about the same as previously: President Kennedy shot today just as his motorcade left downtown Dallas. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and grabbed Mr. Kennedy. She called "Oh, no!" The motorcade sped on. United Press says that the wounds for President Kennedy perhaps could be fatal. Repeating, a bulletin from CBS News: President Kennedy has been shot by a would-be assassin in Dallas, Texas. Stay tuned to CBS News for further details.

Cronkite broke in with a second bulletin just as As the World Turns, which was still being performed live as nobody had been made aware of the interruptions, was about to return from its mid-show station identification break.[153] The serial was then joined in progress, and during the advertising break that followed CBS broke in one more time with Cronkite updating the audience on what was transpiring. This time, he remained on the air filing reports over the bumper slide until the camera was ready, which happened to coincide with CBS’ station identification break at the top of the 2:00 PM hour; Cronkite then told viewers that the network would briefly pause so all of its affiliates could join the broadcast. [154]

ABC and NBC were not broadcasting nationally at the time of the CBS bulletins, and their affiliate stations were airing their own content.[155] In New York, WABC-TV's first bulletin came from Ed Silverman at 1:42 p.m. EST, interrupting a rerun of The Ann Sothern Show. At the same time of ABC-TV's first bulletin, NBC Radio reported the first of three "Hotline Bulletins", each preceded by a "talk-up alert" that provided all NBC-affiliated stations 30 seconds to join their parent network.

Three minutes later, Don Pardo interrupted WNBC-TV's local rerun of Bachelor Father with the news, announcing: "President Kennedy was shot today just as his motorcade left downtown Dallas. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and grabbed Mr. Kennedy. She cried 'Oh no!' The motorcade sped on."[125][156] At 1:53 p.m. EST, NBC broke into programming with an NBC Network bumper slide followed by coverage anchored by Chet Huntley and Bill Ryan.[156] However, NBC's camera was not ready and its coverage was limited to audio-only reports. At 1:57 p.m. EST, just as Frank McGee joined the broadcast, NBC began broadcasting the report when its camera became operational.[157] However, the first few minutes are considered lost, as the network did not begin recording at the start of its coverage, though an audio recording of Pardo's bulletins exists.[158]

Other than for two audio-only bulletins (one following the initial report), ABC did not disrupt its affiliate stations' programming, instead waiting until the network was to return to broadcasting at 2:00 p.m. EST to begin its coverage.

Radio coverage was reported by Don Gardiner (ABC), Allan Jackson (CBS) and (after a top-of-the-hour newscast) Peter Hackes and Edwin Newman (NBC).

Television and radio coverage (from approx. 2:00 to 2:40 p.m. EST)

ABC

Providing the reports for ABC Television were Don Goddard, Ron Cochran, and Ed Silverman in New York, Edward P. Morgan in Washington, Bob Clark (who as noted above had been riding in the motorcade when Kennedy was shot) from Parkland Hospital, and Bill Lord from the Dallas County sheriff's office. As with the other networks, ABC interspersed with their Dallas affiliate WFAA-TV 8 for up-to-date information. Reporting from WFAA were Bob Walker (who had been at Love Field for live coverage of the President's arrival) and Jay Watson (who had remained on the air locally from the time he broke into local programming upon his return from Dealey Plaza). They were later joined by Bob Clark upon his arrival from the hospital.

ABC's initial coverage of the incident was very disorganized. Cochran, ABC's primary news anchor, was on his lunch break when word of the assassination attempt first broke and the network had to call him back to the studio. Silverman was the voice accompanying ABC's first bulletin, broadcast during a rerun episode of Father Knows Best that was airing on a majority of the network's affiliates in the Mountain Time Zone at the time; the surviving videotape of ABC's initial bulletins appears to have been recorded by then-affiliate KTVK in Phoenix, as it contains the interruption of Father Knows Best. The first on-camera report was given by Goddard in the network's news studio, which was too far away from the teletype machines. Goddard then moved to the newsroom and was joined by the returning Cochran, and the technical crew began constructing an impromptu news set around them (ABC did not have studio space ready for such an occasion; NBC had a flash studio in its newsroom and CBS' reports came directly from their own newsroom as they had since they launched an evening newscast earlier in 1963). Cochran and Goddard were forced to stand and awkwardly hold microphones and headsets so they could report the information.

In addition to the disorganization in New York, ABC was not able to switch to Dallas to speak to its correspondents. Only one feed was available to them at first, which came from the Dallas Trade Mart and CBS affiliate KRLD reporter Eddie Barker. CBS had earlier aired snippets of Barker's report, but had cut it off to return to its own reporting of the incident before Barker finished; ABC aired the remainder of the report until the end. The reason that ABC was able to air the CBS affiliate's coverage was due to a pool arrangement the three major Dallas stations agreed to for the President's visit. WBAP was responsible for covering the President's visit to Fort Worth and his departure and landing at Love Field, WFAA was assigned to cover the parade through downtown Dallas, and KRLD was set up at the Dallas Trade Mart for the address the President was to give.

At 2:25 p.m. EST, while attempting to switch to Bob Clark in Dallas, ABC Radio reported that Parkland Hospital said President Kennedy was dead, and then stressed that it was unconfirmed. Upon reporting the news, anchor Don Gardiner said this to his audience:

Ladies and gentlemen, this is a moment trying for all of us. Let us pause, and let us all pray.

ABC Radio then stopped coverage to broadcast orchestral music.[159]

At 2:33 p.m. EST, Cochran reported on ABC Television that the two priests who were called into the hospital to administer the last rites to the President said that he had died from his wounds. Although this was an unconfirmed report, ABC prematurely placed a photo of the President with the words "JOHN F. KENNEDY – 1917–1963" on the screen.

Five minutes later, this photo was again prematurely placed when Cochran received an erroneous report that the President had died at 1:35 p.m. CST when, in fact, he had died at 1:00 p.m. CST. A few minutes following that, Cochran received further information regarding the President's condition and relayed the following to the ABC viewing audience:

Government sources now confirm...we have this from Washington. Government sources now confirm that President Kennedy is dead. So that, apparently, is the final word and an incredible event that I am sure no one except the assassin himself could have possibly imagined would occur on this day.

On ABC Radio, Gardiner reported the news, but did not say whether or not it was official. ABC then switched to Pete Clapper on Capitol Hill for an interview with the Senate's press liaison Richard Reidel. Moments later, the interview was interrupted by Gardiner's report of the President's death:

Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, is dead. The President is dead. Let us pray.

ABC Radio then returned to orchestral music.

CBS

At 2:00 p.m. EST, CBS took an extended station identification break so the affiliates in the Mountain and Pacific time zones could join the rest of the network in covering the story. Cronkite, now at his desk in the newsroom, appeared on camera for the first time and, for the sake of any new viewers who might not have been aware of what was happening, told the audience of the attempt made on the President's life.

From the time the CBS affiliates joined Cronkite in the news room at the top of the hour to approximately 2:38 p.m. EST, the coverage alternated from the CBS Newsroom and Cronkite, to KRLD-TV's Eddie Barker at the Dallas Trade Mart where President Kennedy was to give his luncheon address.

At approximately 2:11 p.m. EST, CBS News correspondent Dan Rather telephoned one of the two priests who performed last rites on Kennedy to confirm that he had indeed been shot. "Yes, he's been shot and he is dead," the priest told Rather. Almost simultaneously at the Trade Mart, a doctor went up to Barker and whispered, "Eddie, he is dead... I called the emergency room and he is DOA." Moments later, as the news cameras panned throughout the Trade Mart crowds, Barker gave this report:

As you can imagine, there are many stories that are coming in now as to the actual condition of the President. One is that he is dead; this cannot be confirmed. Another is that Governor Connally is in the operating room; this we have not confirmed.

Several minutes later, when CBS switched back to KRLD and the Trade Mart for another report, Barker repeated the claim of the President's death, adding "the source would normally be a good one." During this report, as Barker was speaking of security precautions for the President's visit, a Trade Mart employee was shown removing the Presidential seal from the podium where President Kennedy was to have spoken.

CBS Radio's death announcement

At 2:19 p.m. EST, CBS Dallas correspondents Dan Rather and Eddie Barker spoke by telephone to "compare notes, to take stock". Rather was aware that there was an open line to New York as the two of them spoke, but "didn't realize how many people were on that phone line", which included at least three individuals from CBS Radio.[160] Rather, who had "no doubt in his mind" that Kennedy was dead, nevertheless was not delivering official word to CBS Radio, nor was he aware that his discussion with Barker would be construed as such. As Rather spoke to Barker, an individual from CBS Radio asked, "Did you say the president is dead?" Rather replied, "Yes."[160] Based on the call, CBS Radio newsroom supervisor Robert Skedgell wrote "JFK DEAD" on a slip of paper and handed it to CBS Radio news anchor Allan Jackson. At 2:22 p.m. EST, eleven minutes before Kilduff's official announcement, Jackson made the following announcement:

Ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States is dead. John F. Kennedy has died of the wounds he received in an assassination in Dallas less than an hour ago. We repeat: it has just been announced that President Kennedy is dead.[161]

After the announcement, CBS Radio, apparently trying to play "The Star-Spangled Banner", accidentally aired a brief excerpt of an LP Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings played at the wrong speed of 78 RPM.[162] After a few seconds of silence, Jackson repeated the news:

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President Of The United States, is dead at the age of 46. Shot by an assassin as he drove through the streets of Dallas, Texas less than an hour ago. Repeating this: the President is dead, killed in Dallas, Texas by a gunshot wound.[163]

This was followed by an excerpt from the first movement to Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony.[164] After the music, Jackson again repeated the news:

We repeat our announcement that the President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, is dead in Dallas, Texas, of an assassin's bullets. He was shot, and governor Tom Connelly of the state of Texas was shot, as they rode in a motorcade through the streets of Dallas less than an hour ago. Governor Connelly is in serious condition, President John Kennedy is dead. The 35th president of the United States, he was 46 years old. According to the constitution, Vice President Lyndon Johnson will now succeed Mr. Kennedy in office. Mr. Johnson will become the 36th president of the United States, very probably within a few hours upon taking the oath of office.[165]

After Jackson's announcement, his co-anchor Dallas Townsend added:

Well, as a matter of fact, Allan, Lyndon Johnson is now the president whether he takes the Oath or not. He is the president.[166]

Townsend's comment was followed by "The Star-Spangled Banner".

CBS TV

While CBS Radio had taken Dan Rather's earlier discussion with Barker as confirmation of the president's death, there was a debate going on between CBS television network officials as to whether or not to report this development, as Rather's report was not a truly official confirmation. At 2:27 p.m. EST, they decided to give Rather's report to Cronkite, who relayed this to the nation:

We just have a report from our correspondent Dan Rather in Dallas that he has confirmed that President Kennedy is dead. There is still no official confirmation of this. However, it's a report from our correspondent, Dan Rather, in Dallas, Texas.

Approximately five minutes after this, one of the newsroom staff members rushed to Cronkite's desk with another bulletin. As Cronkite read the bulletin, he had to re-read it as he stumbled over his words.

The priest... who were with Kennedy... the two priests who were with Kennedy say that he is dead of his bullet wounds. That seems to be about as close to official as we can get at this time.

Although Cronkite continued to stress that there was no official confirmation, the tone of Cronkite's words seemed to indicate that it would only be a matter of time before the official word came. Three minutes later, he received the same report that ABC's Ron Cochran chose to relay as official word. Cronkite did not do the same, reporting it instead in this context:

And now, from Washington, government sources say that President Kennedy is dead. Those are government sources, still not an official announcement.

Cronkite continued as before while still awaiting word of the official confirmation of the President's death, which at this time had been relayed by Kilduff at the hospital two minutes prior but had not made the press wires yet. After speaking about what Kennedy had done earlier that day in Fort Worth, Cronkite noted that the plane from Fort Worth flew the President to his "rendezvous with death, apparently, in Dallas", although the official bulletin still had not arrived yet.

Immediately after that, at 2:38 p.m. EST, Cronkite remarked on fearful concerns of demonstrations in Dallas similar to the attack of U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson in Dallas the previous month. At that moment, a CBS News employee seen in the background pulled off a sheet from the AP News ticker. He quickly relayed it (off-camera) to Cronkite, who put on his glasses, took a few seconds to read the sheet, and made the announcement:

From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official: [reading AP flash] 'PRESIDENT KENNEDY DIED AT 1 P.M. (CST),'[129] 2:00 Eastern Standard Time, some thirty-eight minutes ago.

After reading the flash, Cronkite took off his glasses so he could consult the studio clock, which established the lapse in time since Kennedy had died. He paused briefly and replaced his eyeglasses, visibly moved for a moment. Cronkite continued:

Vice President Johnson... (clears throat) ...has left the hospital in Dallas, but we do not know to where he has proceeded. Presumably, he will be taking the oath of office shortly and become the thirty-sixth president of the United States.

There was a sense of irony to CBS' coverage of the assassination. On September 2, 1963, Kennedy gave an interview with Cronkite, helping CBS inaugurate network television's first half hour evening newscast.[167]

It should perhaps be noted that CBS did not include any further coverage from Dallas or Washington as the other networks had until after the announcement of Kennedy's death. As coverage continued following the announcement, Charles Collingwood relieved Cronkite in New York while Neil Strawser reported from CBS' Washington bureau and Dan Rather and Eddie Barker provided reports from KRLD in Dallas.

NBC

At NBC-TV, Chet Huntley, Bill Ryan, and Frank McGee anchored from the network's emergency "flash" studio (code name 5HN) in New York, with reports from David Brinkley and Martin Agronsky in Washington, Charles Murphy and Tom Whelan from NBC affiliate WBAP-TV (now KXAS-TV) in Fort Worth, Texas, and Robert MacNeil, who had been in the motorcade, at Parkland Hospital.[168][169] Edwin Newman reported from NBC Radio with periodic simulcast with NBC-TV. NBC Radio's coverage was simulcast in Canada by CBC Radio.[170] Also, the United States' international shortwave broadcaster, Voice of America, relayed portions of NBC's coverage (including the simulcast with the television coverage) as part of its English-language coverage of the tragic news. (A short aircheck of VOA exists in which the announcers on duty attempt to make sense of the conflicting reports about Kennedy's condition, and then the station briefly simulcasts NBC before heading into Polish-language programming at 1:00 p.m. Central Time.)

Throughout the first 35 minutes, there were technical difficulties with the Fort Worth TV relay as well as with the phone link MacNeil was using to report from the hospital.[155] When the coverage began, McGee was waiting for MacNeil to call in with information. While Ryan and Huntley were recounting the information, McGee got MacNeil on the line and told him to recount chronologically what happened.[171] The NBC flash studio had no way of patching calls through the studio speakers, however, so nobody else could hear what MacNeil was saying.[155] While the studio crew worked on a solution, McGee improvised and told MacNeil to relay the information in fragments, which he would then repeat for the audience. While they were talking, Huntley was handed a speaker from off camera and took the receiver from McGee so he could attach it to the earpiece, this enabling MacNeil to be heard. However, by that time there was no further information to report; MacNeil had a medical student from Parkland hold the phone line for him so that he could return to the emergency ward for the latest developments. He would return briefly several minutes later to offer more word on the condition of the President, during which the phone link temporarily worked, but as MacNeil left again the relay cut out. Before he left, he informed McGee that a press conference regarding Kennedy's condition was forthcoming.[171]

At approximately 2:35 p.m. EST, shortly after Ryan reported that a neurosurgeon had just arrived at Parkland to assist in treating Kennedy. Huntley alluded to the last time a president had died in office:

In just this momentary lull, I would assume that the memory of every person listening at this moment has flashed back to that day in April 1945 when Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

However, he was unable to complete his thought. The flash regarding the priests who administered the Last Rites to the President had reached the desk while Huntley was speaking, and Ryan interrupted him to relay this:[45]

Excuse me, Chet. Here is a flash from the Associated Press, dateline Dallas: 'Two priests who were with President Kennedy say he is dead of bullet wounds.' There is no further confirmation, but this is what we have on a flash basis from the Associated Press: 'Two priests in Dallas who were with President Kennedy say he is dead of bullet wounds.' There is no further confirmation. This is the only word we have indicating that the president may, in fact, have lost his life. It has just moved on the Associated Press wires from Dallas. The two priests were called to the hospital to administer the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church. And it is from them, we get the word, that the president has died, that the bullet wounds inflicted on him as he rode in a motorcade through downtown Dallas have been fatal. We will remind you that there is no official confirmation of this from any source as yet.

As this was going on, McGee received a report from Parkland Hospital. Shortly after arriving at the hospital, Vice President Johnson had been advised to begin heading back to Washington to assume executive duties in case he needed to be sworn in. Johnson decided to wait until he received word of Kennedy's condition, which he did at approximately 1:20 PM CST.[138][137] McGee reported to Ryan that a motorcade carrying the Johnsons had just left Parkland Hospital, which Ryan took to be confirmation of the President's death as the priests had reported.

On NBC Radio and CBC Radio, Newman reported the same flash, having received it about half a minute after Ryan did:

Here is a flash from Dallas: 'Two priests who were with President Kennedy say he is dead of bullet wounds suffered in the assassination attempt today.' I repeat, a flash from Dallas: 'Two priests who were with President Kennedy say he is dead of bullet wounds.' This is the latest information we have from Dallas. We are, of course, standing by to give you all available information as it comes to us. I will repeat, with the greatest regret, this flash: 'Two priests who were with President Kennedy say he has died of bullet wounds.'[172]

At that point, both radio networks rejoined NBC-TV where Ryan reported that there may in fact be confirmation of the priests' account of Kennedy's death. The feed then switched back to Charles Murphy at WBAP-TV, who reported that although no official statement had been released by the President's staff, the Dallas Police Department had been notified of Kennedy's death and radioed the word to every one of its officers on duty shortly before the flash from Dallas made the wires.[45]

As Murphy was filing his report, McGee got back in touch with Robert MacNeil, who had just returned from the aforementioned press conference. Partway through the report, the audio link was fixed and MacNeil could be clearly heard in the studio and on the air. McGee was unaware of this, as he simply carried on as he had been:[45]

White House (Acting) Press Secretary... Malcolm Kilduff... has just announced that President Kennedy... died at approximately 1:00 Central Standard Time, which is about 35 minutes ago... (audio enabled) ...after being shot at (after being shot)... by an unknown assailant (by an unknown assailant) ...during a motorcade drive through downtown Dallas (during a motorcade drive through downtown Dallas).

After MacNeil had finished giving all the relevant information available, he left the phone to obtain further information. McGee, wiping a tear from his eye, stood by and kept the phone line open for MacNeil's next update.

KLIF Radio, Dallas

From local radio station KLIF, Gary Delaune relayed the bulletins as received with reports from Joe Long from KLIF News Mobile Unit #4. Long, who had reported the President's arrival at Love Field earlier and filed reports from his news cruiser after he had gotten stuck in traffic in the midst of the chaos,[173] later joined Delaune in the studio; Roy Nichols took over the #4 mobile unit and headed for Parkland Hospital. After a report from the Trade Mart, radio broadcaster and KLIF founder Gordon McLendon returned to the radio station to relieve Delaune. The reporters continuously stressed, as a strict radio station rule of McLendon's, whether the information received is from official or unofficial sources, especially concerning reports of the President's death. At approximately 1:38 p.m. CST, KLIF's Teletype sounded ten bells (indicating an incoming bulletin of utmost importance) and Long was given the official flash:

Gordon McLendon: The President is clearly, gravely, critically, and perhaps fatally wounded. There are strong indications that he may already have expired, although that is not official, we repeat, not official. But, the extent of the injuries to Governor Connally is, uh, a closely shrouded secret at the moment...

Joe Long: President Kennedy is dead, Gordon. This is official word.

Gordon McLendon: Ladies and gentlemen, the President is dead. The President, ladies and gentlemen, is dead at Parkland Hospital in Dallas.

KLIF's continuous coverage would eventually be aired over an ad-hoc radio network of its own, as the station's coverage was fed to KLIF's sister stations in Houston, Louisville, and other cities and reportedly aired (with or without permission) on dozens, possibly hundreds, of others.

Following the official announcement of President Kennedy's death, all three commercial networks suspended their regular programming and commercials for the first time in the short history of television and ran coverage on a non-stop basis for four days.[174] The assassination of President Kennedy was the longest uninterrupted news event in the history of American television until just before 9:00 a.m. EDT, September 11, 2001, when the networks were on the air for 72 hours straight covering the 9/11 terrorist attacks.[175]

United Kingdom

A Reuters tickertape machine reported news of the assassination at GMT 6:42 PM, 12 minutes after the event.

President Kennedy was shot at today while riding in a motor convoy. A photographer reported seeing blood on the President's head.

Granada Television, broadcasting the news program Scene at 6:30 to the north of England from Manchester, reported the news just before GMT 7:00. The BBC shortly followed up with announcements on its three national radio networks, including the program Radio Newsreel which ran from GMT 7:00 to GMT 7:30 PM with a Washington-based BBC journalist providing live updates by phone to an estimated 2.7 million listeners.

On BBC television, the first announcement to air was made at GMT 7:05 PM by a junior and unfamiliar newsreader, John Roberts, just prior to the program Tonight. Tonight continued with its planned edition until around GMT 7:26 PM when Roberts returned to provide updates of Kennedy's critical condition. Shortly after on air he answered a phone call from BBC Monitoring which relayed news of the death of Kennedy as reported by the Voice of America. Roberts' countenance visibly changed and he announced to the audience, "We regret to announce that President Kennedy is dead," before bowing his head and not looking up. For the next 19 minutes the BBC screened its logo and a revolving globe, punctuated by three bulletins read by Roberts. BBC management then decided to revert back to regular programming, screening Here's Harry from GMT 7:45 PM, followed by Dr. Finlay's Casebook, a decision which attracted over 2,000 phone calls and 500 letters and telegrams in complaint.

At GMT 11:00 pm, four hours after the news broke, the BBC broadcast Tribute to President Kennedy, featuring Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home, Liberal leader Jo Grimond and Leader of the Opposition Harold Wilson who had sped from North Wales to the BBC's Manchester studio.

On ITV television, a newsflash interrupted a game show around GMT 7:10 PM, but the program continued, as did Emergency - Ward 10 which followed at GMT 7:30 PM. Ten minutes later the program was cut and an announcement of Kennedy's death was made, and updates continued over the station's interlude card. A recorded programme of solemn music performed by the Hallé Orchestra followed. [176]

Return to Washington

Once back at Air Force One, and only after Mrs. Kennedy and President Kennedy's body had also returned to the plane, Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in by Sarah T. Hughes as the 36th president of the United States at 2:38 p.m. CST.[177][178] One of President Kennedy's aides stayed with his coffin during the swearing-in of Johnson.[179]

At about 6:00 p.m. EST, Air Force One arrived at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C.[180][181][182] The television networks made the switch to the AFB just as the plane touched down.[183] Reporting on the arrival for the TV networks were:

| Network | Reporting | Contributing[184][185] |

|---|---|---|

| ABC | Richard Bate[186] | Frank Reynolds |

| CBS | Charles Von Fremd[187] | Dan Rather |

| NBC | Bob Abernethy & Nancy Dickerson[188][185] | Ray Scherer |

The contributors to the reporting on the arrival for the TV networks contributed along with NBC Director Max Schindler, who directed the coverage of the arrival for the networks, in 1965 when he directed A Conversation with the President at the White House with President Johnson during a conversation with him.[185][184]