James Walker Hood

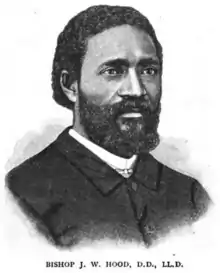

James Walker Hood (May 30, 1831 – October 30, 1918) was an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AME Zion) bishop in North Carolina from 1872 to 1916. Before the Emancipation Proclamation, he was an active abolitionist, and during the American Civil War he went to New Bern, North Carolina where he preached for the church to the black people and soldiers in the area. He was very successful and became an important religious and political leader in North Carolina, becoming "one of the most significant and crucial African American religious and race leaders during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries".[1] By 1887 he had founded over six hundred churches in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina and erected about five hundred church buildings.[2] He was politically and religiously active as well, supporting education, civil rights, and the ordination of women.

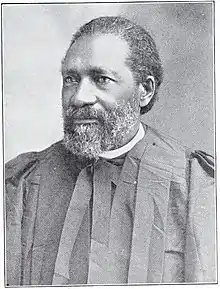

James Walker Hood | |

|---|---|

Hood, c. 1910 | |

| Born | May 30, 1831 |

| Died | October 30, 1918 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Political party | Republican |

| Personal | |

| Religion | African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church |

Early life

James Walker Hood was born in Kennett township, Chester County, Pennsylvania on May 30, 1831[2] to Harriet and Levi Hood and had eleven siblings.[3] Hood fought for his right to ride public transport from boyhood. Between 1848 and 1863, he noted that conductors on the Pennsylvania railroads many times tried to remove him from the first class cars, but rarely succeeded. He also actively spoke against slavery.[2] Hood was first licensed to preach around 1852, and in 1855, Hood moved to New York City and in 1856 was licensed to preach in a branch of the Union Church of Africans in the city.[4]

In 1860 he was ordained deacon in the AME Zion church and sent to the Nova Scotia mission in Halifax.[2] In 1863 he was stationed at Bridgeport, Connecticut, and after six months was appointed missionary by Bishop J. J. Clinton sent to North Carolina to replace another missionary, John Williams, who was not prompt enough in travelling south due to safety issues. Hood arrived in Washington, DC by January 1, 1864, and reached New Bern on January 20.[5]

Move to North Carolina

Clinton's sending of missionaries to North Carolina was at the general invitation to churches for missionaries to his department by General Butler who was in charge of the area at that point in the US Civil War (1861–1865). Black soldiers stationed at New Bern at that time did not have a chaplain, and Hood often preached to the troops. His position was informal and he never held a commission, but he was called "chaplain". Hood was present for attacks on New Bern by Confederate troops before the war ended[2] although not under direct fire. In New Bern, Hood preached at the Andrews Chapel and largely succeeded to make his church the primary church of blacks in the area.[5]

Hood was active in political and social movements as well. In October 1865 in Raleigh, North Carolina, Hood was elected president at what may have been the first convention of colored people held in the South, part of the Colored Conventions Movement.[2] In 1867 he was a delegate at the Constitutional Convention of North Carolina and played such a major part that some opponents called the resulting constitution, "Hood's Constitution". The document was amended in 1875 and many of the provisions Hood fought to include were weakened or removed. His influence was heavily felt in the provision of rights for blacks in homestead law and at public school. He was very active in securing support for the constitution as well. In 1868, he was made a commissioner for the states public schools and assistant superintendent of public instruction in North Carolina and held the positions for three years.[2]

In 1868, he demanded and obtained cabin passage on Cape Fear River steamships, thereby integrating the steamships on those rivers. The agents of the steamers claimed that they only allowed his action because the area was under military authority. However, Hood stated that his right was from God, and the steamships remained integrated after reconstruction ended. Remembering his earlier struggles riding Pennsylvania rail cars, he endeavored to assert his right to ride in otherwise white rail cars in the south as well.[2]

His office in the school board were in Raleigh, while his primary church responsibilities were in Charlotte North Carolina, so he would travel to Charlotte on weekends three Sundays per month to preach. The remaining Sunday he would preach for Methodist and Baptist congregations in Raleigh, as there was not yet an AME Zion church in that city.[2]

Before 1870 he received a commission from General Oliver O. Howard as assistant superintendent of schools in the Freedmen's Bureau. In this role by 1870 he had established a department for schooling for the deaf, dumb, and blind in the Bureau. He also worked to create an integrated State University, but was not successful due to the opposition of Democrats in the state legislature after they gained control of that body in 1870. He was a delegate to the 1872 Republican National Convention and temporary chairman of the Republican State convention in 1876.[2]

National and international prominence

He was elected bishop of the General Conference at its session in North Carolina on July 1, 1872 and served until 1916.[6] He was elected a member of the Ecumenical Conference in London in 1881,[2] and was president of that body in 1891 when it met in Washington DC.[7] He presided over the first day of the centennial gathering of the Methodist Church in 1885 in Baltimore.[2]

As a conservative Bishop, he was not without critics, including progressives within the church such as John W. Smith, John J. Smyer, Alexander Walters, and especially Henry McNeal Turner.[8] However, he was strongly supported in North Carolina and beyond. He published a volume of sermons with an introduction by Atticus Green Haygood[2] in 1884 entitled The Negro in the Christian Pulpit, which was the first collection of sermons published by an African American.[7]

Other activities and social positions

He established Livingstone College in North Carolina in 1882. He also established and contributed to journals associated with AME Zion church, Star of Zion newspaper and AMEZ Quarterly Review.[9] He was a strong advocate against smoking and drinking,[2] and supported the ordination of women.[10] He worked to merge black Methodist churches, supported the 1898 Spanish–American War, and worked for civil rights.[9]

He was a Master Mason, eventually becoming the Grand Master of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons, North Carolina Jurisdiction,[2] and later was a founder of the King Solomon Lodge,[11] affiliated with Prince Hall Masons and the first order of Masons among blacks in North Carolina.[6]

Family life and death

He married three times. In about 1853 he married Hannah L Ralph, who died of consumption in 1855. In about 1858 he married Sophia J. Nugent of Washington City. They had four children.[2] and Sophia died September 13, 1875.[13] In June, 1877 he married Keziah P. McKoy. They had three children.[2] His six children who survived infancy were Gertrude C. (Miller), Lillian A. (McCallum), Margaret J. (Banks), Maude E., Joseph Jackson, and James Walker, Jr. Keziah served for some years as president and secretary of Zion's Women's Home and Foreign Missionary Society and published a column in Star of Zion.[14]

On October 30, 1918, James Walker Hood died in Fayetteville, North Carolina.[15]

Bibliography

- Hood, James Walker. The Negro in the Christian Pulpit, Or, The Two Characters and Two Destinies: As Delineated in Twenty-one Practical Sermons. Edwards, Broughton, 1884.

- Hood, James Walker. One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church: Or, The Centennial of African Methodism. AME Zion Book Concern, 1895.

- Hood, James Walker. The Plan of the Apocalypse. P. Anstadt & Sons, 1900.

References

- Martin 1999, p 3

- William J. Simmons, and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p 133–143

- Martin 1999, p 24

- Martin 1999, p xvi

- Martin 1999, p 51

- Martin, 1999, p 4, 88

- Anthony B. Pinn, African American Religious Cultures, ABC-CLIO, 2009, p71

- Martin 1999, p 194, xvi

- Hill, Samuel S., Charles H. Lippy, and Charles Reagan Wilson. Encyclopedia of Religion in the South. Mercer University Press, 2005. p386

- Martin 1999, p 172

- Bishir, Catherine W. Crafting Lives: African American Artisans in New Bern, North Carolina, 1770–1900. UNC Press Books, 2013. p 186

- Hood, James Walker. One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church: Or, The Centennial of African Methodism. AME Zion Book Concern, 1895. p 283 accessed August 26, 2016 at https://books.google.com/books?id=aPc4AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA283

- Martin 1999 p 31

- Martin 1999, p 42

- Martin 1999, p 194

Further reading

- Martin, Sandy Dwayne. For God and Race: The Religious and Political Leadership of AMEZ Bishop James Walker Hood. Univ of South Carolina Press, 1999.

External links

![]() Media related to James Walker Hood at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James Walker Hood at Wikimedia Commons