Japanese submarine I-1

I-1 was a J1 type submarine of the Imperial Japanese Navy. She was a large cruiser submarine displacing 2,135 tons and was the lead unit of the four submarines of her class. Commissioned in 1926, she served in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. During the latter conflict she operated in support of the attack on Pearl Harbor, conducted anti-shipping patrols in the Indian Ocean, and took part in the Aleutian Islands campaign and the Guadalcanal campaign. In January 1943, during the Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal, Operation Ke, the Royal New Zealand Navy minesweeper corvettes HMNZS Kiwi and HMNZS Moa intercepted her, and she was wrecked at Kamimbo Bay on the coast of Guadalcanal after the ensuing surface battle.[2][3]

I-1 in 1930 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Submarine Cruiser No. 74 |

| Builder | Kawasaki, Kobe, Japan |

| Laid down | 12 March 1923 |

| Launched | 15 October 1924 |

| Renamed | I-1 on 1 November 1924 |

| Completed | Late February 1926 |

| Commissioned | 10 March 1926 |

| Decommissioned | 5 November 1929 |

| Recommissioned | 15 November 1930 |

| Decommissioned | 15 November 1935 |

| Recommissioned | 15 February 1936 |

| Decommissioned | 15 November 1939 |

| Recommissioned | 15 November 1940 |

| Fate | Wrecked 29 January 1943 |

| Stricken | 1 April 1943 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | J1 type submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 320 ft (98 m) |

| Beam | 30 ft (9.1 m) |

| Draught | 16.5 ft (5.0 m) |

| Propulsion | twin shaft MAN 10 cylinder

4 stroke diesels giving 6000 bhp two electric motors of 2600 ehp |

| Speed | 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) (surfaced) 8 kn (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) (submerged) |

| Range | 24,400 nmi (45,200 km; 28,100 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Test depth | 80 m (262 ft) |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 1 x 46 ft (14 m) Daihatsu (added August–September 1942) |

| Complement | 68 officers and men |

| Armament |

|

Construction and commissioning

Built by Kawasaki at Kobe, Japan, I-2 was laid down on 12 March 1923 with the name Submarine Cruiser No. 74.[4][5] She was launched on 15 October 1924.[4][5] Renamed I-1 on 1 November 1924, she was completed in late February 1926 and underwent sea trials—in which several German ship constructors participated—in the Seto Inland Sea off Awaji Island.[5] The Imperial Japanese Navy accepted her for service and commissioned her on 10 March 1926.[4][5]

Service history

Early service

On the day of her commissioning, I-1 was attached to the Yokosuka Naval District.[4][5] On 1 August 1926, she and her sister ship I-2 were assigned to Submarine Division 7 in Submarine Squadron 2 in the 2nd Fleet, a component of the Combined Fleet.[4][5] On 1 July 1927, the division was reassigned to the Yokosuka Defense Division in the Yokosuka Naval District,[4] and on 15 September 1927, when Submarine Division 7 began another tour with Submarine Squadron 2 in the 2nd Fleet,[6] I-1 was removed from the division and reassigned directly to the Yokosuka Naval District.[4] She returned to the division on 10 September 1928 during its assignment to Submarine Squadron 2.[4] At 10:35 on 28 November 1928, as Submarine Division 7 returned to Yokosuka, Japan, in heavy seas and limited visibility, I-1 ran aground off Yokosuka.[4][5] She suffered minor damage.[5] No flooding occurred, but she was drydocked at Yokosuka to have her hull inspected.[5] On 5 November 1929, I-1 was decommissioned and placed in reserve,[4][5] and on 30 November 1929 Submarine Division 7 again was assigned to the Yokosuka Defense Division in the Yokosuka Naval District.[4]

While in reserve, I-1 underwent modernization, in which her German-made diesel engines and entire battery installation were replaced.[5] On 1 August 1930, Submarine Division 7 began an assignment to Submarine Squadron 1 in the 1st Fleet, a component of the Combined Fleet,[4] and, with her modernization work completed, I-1 was recommissioned on 15 November 1930[4][5] and rejoined the division.

On 1 October 1931, Submarine Division 7 was reassigned to the Yokosuka Defense Division in the Yokosuka Naval District,[4] but it began another tour of duty in Submarine Squadron 1 in the 1st Fleet on 1 December 1931.[4] It completed this assignment on 1 October 1932 and again was assigned to the Yokosuka Defense Division in the Yokosuka Naval District,[4] then returned to Submarine Squadron 1 in the 1st Fleet for a third time on either 15 November 1933[4] or 15 November 1934,[5] according to different sources.

I-1 got underway from Sasebo, Japan, in company with the other vessels of Submarine Squadron 1 — I-2 and I-3 of Submarine Division 7 and I-4, I-5, and I-6 of Submarine Division 8 — on 29 March 1935 for a training cruise in Chinese waters.[4][7][8][9][10][11] The six submarines concluded the cruise with their return to Sasebo on 4 April 1935.[4][7][8][9][10][11] On 15 November 1935, the division was reassigned to the Yokosuka Defense Squadron in the Yokosuka Naval District,[4] and that day I-1 again was decommissioned and placed in reserve to undergo reconstruction.[4][5]

While I-1 was out of commission, her American-made sonar was replaced by a sonar system manufactured in Japan and her conning tower was streamlined.[5] Submarine Division 7 returned to duty with Submarine Squadron 1 in the 1st Fleet on 20 January 1936[4] and, after her reconstruction was complete, I-1 was recommissioned on 15 February 1936[4][5] and rejoined the division. On 27 March 1937, I-1 departed Sasebo in company with I-2, I-3, I-4, I-5, and I-6 for training in the vicinity of Qingdao, China.[4][7][8][9][10][11][12] The six submarines concluded the training cruise with their arrival at Ariake Bay on 6 April 1937.[4][5][7][8][9][10][11]

Second Sino-Japanese War

On 7 July 1937 the first day of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident took place, beginning the Second Sino-Japanese War.[12] In September 1937, Submarine Squadron 1 was reassigned to the 3rd Fleet,[13] which in turn was subordinated to the China Area Fleet for service in Chinese waters.[13] The squadron, consisting of I-1, I-2, I-3, I-4, I-5, and I-6,[13] deployed to a base at Hong Kong with the submarine tenders Chōgei and Taigei in September 1937.[13] From Hong Kong, the submarines began operations in support of a Japanese blockade of China and patrols of China′s central and southern coast.[13] From 20[4] or 21[5] (according to different sources) to 23 August 1937, all six submarines of Submarine Squadron 1 operated in the East China Sea as distant cover for an operation in which the battleships Nagato, Mutsu, Haruna, and Kirishima and the light cruiser Isuzu ferried troops from Tadotsu, Japan, to Shanghai, China.[5]

Submarine Squadron 1 was based at Hong Kong until the autumn of 1938.[13] In an effort to reduce international tensions over the conflict in China, Japan withdrew its submarines from Chinese waters in December 1938.[13]

1938–1941

Submarine Division 7 was reassigned to the Submarine School at Kure, Japan, on 15 December 1938,[4] and was reduced to the Third Reserve in the Yokosuka Naval District on 15 November 1939.[4] While in reserve, I-1 underwent a refit, during which impulse tanks were installed on her Type 15 torpedo tubes and her collapsible radio masts were removed.[5] Along with the rest of her division, I-1 returned to active service on 15 November 1940, when the division was resubordinated to Submarine Squadron 2 in the 6th Fleet, a component of the Combined Fleet.[4][5]

On 10 November 1941, the commander of the 6th Fleet, Vice Admiral Mitsumi Shimizu, gathered the commanding officers of the fleet′s submarines together for a meeting aboard his flagship, the light cruiser Katori, anchored in Saeki Bay.[5] His chief of staff briefed them on the upcoming attack on Pearl Harbor, which would bring Japan and the United States into World War II.[5] As the Imperial Japanese Navy began to deploy for the upcoming conflict in the Pacific, the rest of Submarine Squadron 1 got underway from Yokosuka on 16 November 1941, bound for the Hawaiian Islands.[12] At the time, I-1 was undergoing repairs—during which a very low frequency receiver was installed aboard her—at Yokosuka, so her departure was delayed, but on 23 November 1941 she too left Yokosuka. After an overnight stop in Tateyama Bight, she got underway for Hawaii, proceeding at flank speed to catch up with her squadron mates and remaining on the surface until within 600 nautical miles (1,100 km; 690 mi) of Oahu.

By 6 December 1941, Submarine Squadron 1 was on station across a portion of the Pacific Ocean stretching from northwest to northeast of Oahu, and I-1 arrived in her patrol area, in the westernmost part of the Kauai Channel between Kauai and Oahu, that day.[5] The submarines had orders to attack any ships which sortied from Pearl Harbor during or after the attack, which was scheduled for the morning of 7 December 1941.[5]

First war patrol

At 07:30 on 7 December 1941, I-1 sighted an Aichi E13A1 (Allied reporting name "Jake") floatplane returning to the heavy cruiser Tone after a reconnaissance flight over Lahaina Roads off Maui.[5] In the following days, she was attacked repeatedly by aircraft; although she suffered no damage, she began to keep her negative buoyancy tank flooded when surfaced so that she could dive more quickly.[5] While on the surface at 05:30 on 10 December 1941 she sighted a United States Navy aircraft carrier—probably USS Enterprise (CV-6)—24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) north-northeast of Kahala Point on Kauai but was forced to submerge and was unable to transmit a sighting report for almost 12 hours.[5] She often is credited with a bombardment of Kahului, Maui, on 15 December 1941, although it actually was the submarine I-75 that shelled Kahului that day.[5]

On 27 December 1941, I-1 received orders from the commander of Submarine Squadron 2 aboard his flagship I-7 to bombard the harbor at Hilo on the island of Hawaii on 30 December 1941.[5] She arrived off Hilo on 30 December and conducted a periscope reconnaissance of the harbor, sighting the U.S. Navy seaplane tender USS Hulbert (AVD-6)—which she misidentified as a small transport—moored there.[5] After dark, she surfaced and fired ten 140-millimeter (5.5 in) rounds from her deck guns at Hulbert.[5] One shell hit the pier next to Hulbert and another started a fire near Hilo Airport.[5] None hit Hulbert, and Hulbert and a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps battery returned fire.[5] Mistakenly claiming moderate damage to Hulbert, I-1 ceased fire and left the area.[5]

I-1 attacked a transport south of the Kauai Channel on 7 January 1942, but scored no hits.[5] On 9 January 1942, she was ordered to divert from her patrol and search for the United States Navy aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2), which the submarine I-18 had sighted northeast of Johnston Island.[5] but she did not find Lexington. She arrived at Kwajalein in company with I-2 and I-3 on 22 January 1942.[5] The three submarines departed Kwajalein on 24 January 1942 bound for Yokosuka, which I-1 reached on 1 February 1942.[5]

Second war patrol

While I-1 was at Yokosuka, Submarine Squadron 2—consisting of I-1, I-2, I-3, I-4, I-5, I-6, and I-7—was assigned to the Dutch East Indies Invasion Force in the Southeast Area Force on 8 February 1942.[5] I-1 departed Yokosuka on 13 February 1942 bound for Palau, which she reached on 16 February.[5] After refueling from the oiler Fujisan Maru, she got back underway for the Netherlands East Indies on 17 February 1942 in company with I-2 and I-3.[5] She stopped at Staring Bay on the Southeast Peninsula of Celebes just southeast of Kendari, then put back to sea at 17:00 on 23 February 1942 to begin her second war patrol, bound for the Timor Sea[5] and Indian Ocean. Shortly after she left Staring Bay, her starboard diesel engine′s crankshaft broke down, but she pushed on, conducting most of her patrol on only one shaft.[5]

I-1 was on the surface in the Indian Ocean off Western Australia 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi) northwest of Shark Bay early on the morning of 3 March 1942 when she sighted smoke from Dutch 8,806-ton armed cargo ship Siantar, which was on a voyage from Tjilatjap, Java, to Australia.[5] She submerged and fired a torpedo at Siantar.[5] It missed.[5] At 06:30, she surfaced on Siantar's port beam and opened fire with her forward 140-millimeter (5.5 in) deck gun.[5] Siantar worked up to full speed and fired back at I-1 with her 75-millimeter gun, but it jammed after only a few shots.[5] I-1's second hit knocked down Siantar's radio antenna.[5] A fire broke out aboard Siantar, and her crew abandoned ship.[5] After scoring about 30 hits on Siantar, I-1 fired another torpedo at her, and about ten minutes later Siantar sank by the stern at around 07:00 at 21°20′S 108°45′E.[5] Out of her crew of 58, Siantar suffered 21 killed.[5]

On 9 March 1942, I-1 captured a canoe carrying five Australian Army personnel trying to reach Australia from Dutch Timor.[5] On 11 March 1942, she reached Staring Bay, where she moored alongside the submarine tender Santos Maru.[5] She transferred her prisoners to a hospital ship.[5] On 15 March 1942 she got underway for Yokosuka, which she reached on 27 March 1942.[5]

March–June

After arriving at Yokosuka, I-1 was drydocked for repairs to her starboard diesel engine[5] and its crankshaft. She also underwent an overhaul in which shipyard workers replaced the 7.7-mm machine gun on her bridge with a 13.2-mm Type 93 machine gun and her Zeiss 3-meter (10 ft) rangefinder with a Japanese Type 97 rangefinder, removed some of the armor protecting her torpedo storage compartment, and installed an automatic trim system.[5] On 10 April 1942, she was reassigned along with I-2 and I-3 to the Advance Force.[5] On 18 April 1942, 16 United States Army Air Forces B-25 Mitchell bombers launched by the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) struck targets on Honshu in the Doolittle Raid.[5] One B-25 targeted Yokosuka, and the members of I-1's crew on deck saw it damage the drydocked aircraft carrier Ryūhō, which was undergoing conversion from the submarine tender Taigei.[5]

On 7 June 1942, I-1 took part in experiments in Tokyo Bay with a kite balloon intended for use by merchant ships.[5] She made several mock attack runs against a ship carrying a prototype of the balloon.[5]

Fourth war patrol

While I-1 was at Yokosuka, the Aleutian Islands campaign began on 3–4 June 1942 with a Japanese air raid on Dutch Harbor, Alaska, followed quickly by the unopposed Japanese occupation in the Aleutian Islands of Attu on 5 June and Kiska on 7 June 1942. On 10 June 1942, I-1, I-2, I-3, I-4, I-5, I-6, and I-7 were reassigned to the Northern Force for duty in the Aleutians, and on 11 June 1942 I-1 set out for Aleutian waters in company with I-2, I-3, I-4, and I-7 to begin her fourth war patrol.[5] On 20 June 1942, I-1, I-2, and I-3 joined the "K" patrol line in the North Pacific Ocean between 48°N 178°W and 50°N 178°W.[5] In mid-July 1942, an unidentified American warship—possibly the United States Coast Guard cutter USCGC Onondaga (WPG-79)—attacked I-1 in the North Pacific Ocean south of Adak Island and pursued her for 19 hours before I-1 finally dived to 260 feet (79 m) and escaped.[5] On 20 July 1942, I-1 was reassigned to the Advance Force and received orders that day to return to Yokosuka, which she reached on 1 August 1942.[5]

Guadalcanal campaign, 1942

During I-1's stay at Yokosuka, the Guadalcanal campaign began on 7 August 1942 with U.S. amphibious landings on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, Florida Island, Gavutu, and Tanambogo in the southeastern Solomon Islands.[5] On 20 August 1942, Submarine Squadron 2 was disbanded.[5] In late August 1942, I-2 underwent work at Yokosuka Navy Yard in which her after 140-millimeter (5.5 in) deck gun was removed and a mounting for a waterproofed 46-foot (14 m) Daihatsu-class landing craft was installed abaft her conning tower, which improved her ability to transport supplies to Japanese forces ashore in the Solomon Islands.[5] With the work completed in early September 1942, she began exercises with the Maizuru 4th Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), which had been designated as "Special Landing Unit" for a raid the Japanese planned on Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides.[5] I-1 was to land the SNLF personnel for the raid.[5]

On 8 September 1942 I-1 departed Yokosuka bound for Truk, where she arrived on 14 September 1942.[5] On 15 September 1942, the commander-in-chief of the 6th Fleet, Vice Admiral Teruhisa Komatsu, inspected her Daihatsu mounting installation.[5] She left Truk on 17 September 1942 and arrived on 22 September 1942 at Rabaul on New Britain,[5] While there, she was reassigned to the Outer South Seas Force in the 8th Fleet along with I-2 and I-3 on 24 September 1942.[5] She set out on 25 September 1942 to support a landing at Rabi, New Guinea, but soon was recalled, and returned to Rabaul on 27 September 1942.[5]

I-1 got underway on 1 October 1942 to carry supplies to a detachment of the Sasebo 5th SNLF on Goodenough Island, carrying a Daihatsu, the Daihatsu's three-man crew, and a cargo of food and ammunition.[5] At 22:40 on 3 October 1942 she surfaced off Kilia Mission on the southwestern tip of Goodenough Island and the Daihatsu took her cargo to shore.[5] She embarked 71 wounded SLNF personnel and the cremated remains of 13 others, recovered the Daihatsu, and returned to Rabaul, which she reached at 13:30 on 6 October 1942.[5] She set out again with another koad of food and ammunition on 11 October 1942.[5] She surfaced off Kilia Mission at 18:30 on 13 October and launched her Daihatsu. Allied intelligence had warned of her arrival, and a Royal Australian Air Force Lockheed Hudson Mark IIIA patrol bomber of No. 32 Squadron attacked the landing area, dropping flares and bombs, and I-1 submerged and departed, leaving her Daihatsu behind.[5] She reached Rabaul on 18 October 1942.[5]

While I-1 was at sea, a floatplane from I-7 made a reconnaissance flight over Espiritu Santo on 17 October 1942, finding a significant Allied naval force there.[5] The Japanese decided to cancel the SNLF raid on Espiritu Santo that I-1 had trained to participate in.[5]

On 17 October 1942, I-1 was reassigned to the Advance Force, and on 22 October 1942 she left Rabaul to join a submarine patrol group operating south of San Cristobal in advance of the upcoming Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands,[5] fought from 25 to 27 October. On 28 October 1942, she received orders to search for downed Japanese air crews in the vicinity of the Stewart Islands.[5] She began to search the waters around the islands on 29 October, but soon had to abort her search when her starboard crankshaft failed again.[5] A U.S. Navy PBY-5 Catalina of Patrol Squadron 11 (VP-11) reported attacking a submarine on 29 October 1942 at 13°15′S 162°45′E, and its target most likely was I-1.[5] I-1 proceeded to Truk.[5] She departed Truk at 17:00 on 13 November 1942 bound for Yokosuka, which she reached at 16:30 on 20 November 1942.[5]

November 1942–January 1943

At Yokosuka, I-1 underwent repairs to her starboard diesel engine and electric motor.[5] Her Daihatsu mounting also was reworked.[5] From 16 to 23 December 1942, she was drydocked for hull maintenance.[5] Her repairs were completed on 30 December 1942,[5] and on 2 January 1943 she got underway at 08:00 to conduct Daihatsu launch tests off Nojimazaki.[5] She was back in port by 12:00.[5]

On 3 January 1943, I-1 put to sea from Yokosuka bound for Truk, which she reached at 18:00 on 10 January 1943.[5] After arriving, she unloaded all but two of her torpedoes[5] and received her Daihatsu. At 06:30 on 12 January 1943 she put to sea to conduct Daihatsu launch tests, but was back at her anchorage at 08:30 to repair the air induction valve for her diesel engines.[5] She conducted more launch tests on 14 January, and on 15 January she got underway at 13:00 for nighttime launch tests, returning to port by 20:00.[5]

Guadalcanal campaign, 1943

At 19:00 on 16 January 1943, I-1 left Truk for Rabaul, where she arrived at 07:30 on 20 January 1943.[5] She took aboard a cargo of rubber containers loaded with two days of food rations—rice, bean paste, curry, ham, and sausages—for 3,000 men.[5] At 16:00 on 24 January 1943, she departed Rabaul bound for Guadalcanal, where she was to deliver her cargo at Kamimbo Bay on the island's northwest coast.[5]

On 26 January 1943, the commander of Allied naval forces in the Solomon Islands informed all Allied ships in the Guadalcanal–Tulagi area of the possibility of Japanese supply submarines arriving at Kamimbo Bay on the evenings of 26, 27, and 29 January 1943.[5] The Royal New Zealand Navy minesweeper corvettes HMNZS Kiwi and HMNZS Moa received orders to conduct an antisubmarine patrol in the Kamimbo Bay area.[5] For its part, the Japanese 6th Fleet warned Submarine Division 7 that Allied motor torpedo boats were operating in the vicinity of Kamimbo Bay and advised them to unload supplies only after dark.[5]

Loss

I-1 surfaced off Kamimbo Bay in a heavy rain squall at 20:30 on 29 January 1943 and headed towards shore, trimmed with her decks awash.[5][14] At 20:35,[14] Kiwi, which was patrolling with Moa off Kamimbo Bay, detected I-1, first with her listening gear and then with asdic, at a range of 3,000 yards (2,700 m).[5][14][15] Moa attempted to confirm the contact, but could not.[5][14] Kiwi closed the range.[5][14] When one of I-1's lookouts sighted Kiwi and Moa—misidentifying them as torpedo boats—I-1 turned to port and submerged, diving to 100 feet (30 m), and rigging for silent running.[5][14] Kiwi saw I-1 submerging and moved in to attack, dropping 12 depth charges in two patterns of six.[5][14] The depth charges detonated close to I-1, knocking several of her men off their feet, and I-1 sprang a leak in her aft provision room.[5][14]

Kiwi's second attack at 20:40 was crippling.[5][14] It disabled I-1's pumps, steering engine, and port propeller shaft, and ruptured her high-pressure manifold, sending a fine water mist across her control room.[5][14] Her main switchboard partially short-circuited and all lighting went out.[5][14] I-1 began an uncontrolled descent with a down-angle of 45 degrees.[5][14] Her commanding officer ordered the forward main ballast tanks blown and full reverse on the remaining operational propeller shaft, stopping the descent, but not before I-1, whose test depth was only 210 feet (64 m), reached an estimated depth of 590 feet (180 m).[5][14] A serious leak began in the forward torpedo room and seawater flooded I-1's batteries, releasing deadly chlorine gas.[5][14]

Around 21:00, as Kiwi began a third attack, I-1 surfaced 2,000 yards (1,800 m) off Kiwi's starboard beam.[5][14][15] Down by the bow, I-1 headed for the shore of Guadalcanal to beach herself, using her starboard diesel and making 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph).[5][14] Her commanding officer personally took the helm and her gun crews manned her 140-millimeter (5.5 in) deck gun and the 13.2-millimeter machine gun on her bridge.[5][14] Kiwi illuminated I-1 with her 10-inch (254 mm) searchlight[5][14] and Moa fired star shells to further illuminate the scene,[5][14] Kiwi opened fire at point-blank range with a 4-inch (102 mm) gun and an Oerlikon 20 mm cannon,[5][14][15] hitting I-1 with her third 4-inch (102 mm) round.[15] Her gunfire raked I-1's conning tower and bridge, knocking out her machine gun, silencing her deck gun, setting her Daihatsu on fire, and killing her commanding officer and most of her bridge crew and gunners.[5][14] With no guidance from her bridge, I-1 began a slow turn to starboard.[5][14] After I-1's navigator came up from below and found everyone on her bridge and deck dead or incapacitated, her torpedo officer assumed command.[5][14] Believing that the New Zealanders intended to board and capture I-1, he prepared the submarine to repel boarders, sending a reserve gun crew on deck to man her deck gun, ordering all surviving officers to arm themselves with their swords, and issuing Arisaka Type 38 carbines to the four best marksmen among the surviving crew.[5][14]

At 21:20, Kiwi turned toward I-1 at full speed at a distance of 400 yards (370 m).[5][14][15] I-1's gunners were unable to hit Kiwi, which was partially shielded by I-1's conning tower, and Kiwi rammed her on her port side abaft her conning tower.[5][14] As Kiwi backed off, she came into the unobstructed field of fire of I-1's deck gun, and I-1's gunners claimed hits that set Kiwi on fire, although in fact no fire broke out aboard Kiwi.[5][14] Believing they were in combat with torpedo boats, I-1's lookouts also reported seeing three torpedoes pass close aboard,[5][14] although the two New Zealand corvettes had no torpedo armament.

Kiwi rammed I-1 a second time, achieving a glancing blow that crushed one of I-1's foreplanes.[5][14] Armed with swords, I-1's navigator and first lieutenant tried unsuccessfully to board Kiwi;[15] the navigator grabbed Kiwi's upper deck rail, but was thrown overboard as Kiwi recoiled off I-1's hull.[5][14] Kiwi again rammed I-1, this time on her starboard side, and rode up on her afterdeck.[5][14] Kiwi damaged her own stem and asdic gear, but she punched a hole in one of I-1's main ballast tanks and disabled all but one of the submarine′s bilge pumps, and I-1 developed an increasing starboard list.[5][14] Damaged and with her 4-inch (102 mm) gun overheating, Kiwi pulled away from I-1[15] and Moa continued the chase, firing at I-1 while illuminating her with a searchlight and star shells.[5][14] She hit I-1 repeatedly, but the submarine′s upper armor deflected some of Moa's shells and splashes from near misses put out the fire that had been raging in her Daihatsu.[5][14] I-1 continued toward Guadalcanal at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[15]

At 23:15, I-1 ran hard aground on Fish Reef off the coast of Guadalcanal, 330 yards (300 m) north of Kamimbo Bay.[5][14] The entire after half of her hull flooded, and she developed a heavy list to starboard.[5][14] Sixty-six men abandoned ship, and not long afterward I-1 sank at 09°13′S 159°40′E.[5][14] She came to rest with 15 feet (4.6 m) of her bow projecting from the water at a 45-degree angle.[5][14]

I-1 suffered 27 killed or missing in the battle with Kiwi and Moa.[5][14] Sixty-eight men survived, including two men who went overboard during the battle and swam to Guadalcanal separately from the other survivors.[5][14] The only fatality on the New Zealand side was Kiwi's searchlight operator, who remained at his post despite suffering a mortal gunshot wound during Kiwi's second ramming attempt and died two days later.[5][15] Between them, the two corvettes expended fifty-eight 4-inch (102 mm) rounds, claiming 17 hits and seven probable hits, as well as an estimated 1,259 rounds of Oerlikon ammunition and 3,500 rounds from small arms.[15]

Salvage and demolition attempts

Moa patrolled off I-1's wreck until dawn on 30 January 1943, when she closed to inspect it.[5][15] She found two survivors at the wreck, capturing one and killing the other with machine-gun fire.[5][15] She also retrieved nautical charts and what she believed was a code book, although it more likely was I-1's logbook.[5] Japanese artillery ashore opened fire on Moa, forcing her to leave the area.[15]

Sixty-three of I-1's survivors were evacuated from Guadalcanal on 1 February 1943.[5] When they reached Rabaul and were debriefed, the Japanese concluded that code materials aboard her wreck were in danger of compromise.[5] Meanwhile, I-1's torpedo officer, two of her junior officers, and 11 men from Japanese destroyers reached the wreck in a Daihatsu after 19:00 on 2 February 1943.[5] They attached two depth charges and four smaller demolition charges to the wreck and set them off in an attempt to destroy it by detonating torpedoes still aboard I-1.[5] Although the torpedoes did not explode and the wreck was not destroyed, the depth charges caused enough damage to prevent salvage of I-1.[5] Evacuated from Guadalcanal on 7 February 1943—the day the Guadalcanal campaign ended with the completion of Operation Ke, the Japanese evacuation of all forces from the island—the three officers subsequently reported their failure to destroy the wreck after they arrived at Rabaul.[5]

On 10 February 1943, the Japanese made another attempt to destroy I-1's wreck, when nine Buin-based Aichi D3A1 (Allied reporting name "Val") dive bombers from Bougainville escorted by 28 Mitsubishi A6M Zero (Allied reporting name "Zeke") fighters attacked it.[5] Most of the dive bombers failed to find the wreck, but one scored a hit on it near the conning tower with a 250-kilogram (551 lb) bomb.[5] On 11 February 1943, I-2 departed Shortland Island with I-1's torpedo officer aboard, tasked with finding and destroying I-1's wreck.[12]

As the Japanese feared, the Allies began to investigate I-1's wreck in the hope of recovering intelligence from it. On 11 February 1943, the day I-2 got underway from Shortland Island, the U.S. Navy PT boat PT-65 arrived at the wreck carrying United States Army intelligence officers[5] who assessed the potential of the wreck to yield useful information. The submarine rescue vessel USS Ortolan (ASR-5) inspected the wreck of I-1 on 13 February 1943, and her divers recovered five code books and other important communications documents.[5] That evening, I-2 penetrated Kamimbo Bay to a distance of only 1,100 yards (1,010 m) from shore but failed to find I-1's wreck.[5][12] On 15 February 1943—the day the Imperial Japanese Navy decided to consider all code materials aboard I-1 compromised and revised and upgraded its codes[5]—she tried again, reaching a point 1.4 nautical miles (2.6 km; 1.6 mi) from the coast before motor torpedo boats attacked her with depth charges.[5][12] After an aircraft also attacked her at 11:20, I-2 gave up and returned to Shortland Island.[12] Ultimately, the U.S. Navy reportedly salvaged code books, charts, manuals, the ship's log, and other secret documents, as well as equipment, from the wreck of I-1.[3]

The Japanese struck I-1 from the Navy list on 1 April 1943.[5]

Postscript

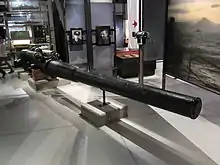

In 1968, I-1's main deck gun was salvaged and brought to Auckland, New Zealand, aboard the frigate HMNZS Otago[16] for display at the Torpedo Bay Navy Museum.

In 1972, an Australian treasure hunter in search of valuable metals blew up the bow section of I-1.[5] With live torpedoes still inside, the explosion destroyed the forward third of the submarine, with the bow section split open.[5] The after two-thirds of the wreck remained intact.[5] I-1's wreck lies on an incline with the remains of her bow in 45 feet (14 m) of water and her stern at a depth of 90 feet (27 m).[5]

I-1's pennant is on display in the United States at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas.[17]

References

Footnotes

- Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two ISBN 0-87021-459-4 p.191

- "Moa and Kiwi bag a sub". New Zealand History. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Owen, David (2007). Anti-submarine warfare : an illustrated history. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 179. ISBN 9781591140146.

- I-1 ijnsubsite.com 1 July 2020 Accessed 27 January 2022

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2016). "IJN Submarine I-1: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Submarine Division 7 ijnsubsite.com Accessed 29 January 2022

- I-2 ijnsubsite.com 15 April 2018 Accessed 27 January 2022

- I-3 ijnsubsite.com 3 May 2018 Accessed 27 January 2022

- I-4 ijnsubsite.com 18 May 2018 Accessed 27 January 2022

- I-5 ijnsubsite.com 18 May 2018 Accessed 27 January 2022

- I-6 ijnsubsite.com 18 September 2019 Accessed 27 January 2022

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2013). "IJN Submarine I-2: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Boyd and Yoshida, p. 54.

- Bertke, Kindell, and Smith, p. 259.

- Wright, Matthew, "David and Goliath in the Solomons: the ‘pocket corvettes’ Kiwi and Moa vs I-1," navygeneralboard.com, May 6, 2019 Retrieved 15 August 2020

- "Remains of I-1 Japanese submarine". New Zealand History. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- McLeod, Tom. "I-1 pennant displayed at Museum of the Pacific". Pacific Wrecks Incorporated. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Bertke, Donald A., Don Kindall, and Gordon Smith. World War II Sea War, Volume 8: Guadalcanal Secured: Day-to-Day Naval Actions December 1942–January 1943. Dayton, Ohio: Bertke Publicarions, 2015. ISBN 978-1-937470-14-2.

- Boyd, Carl, and Akihiko Yoshida. The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1995. ISBN 1-55750-015-0.