History of Jardine Matheson & Co.

Jardine, Matheson & Co., later Jardine, Matheson & Co., Ltd., forerunner of today's Jardine Matheson Holdings, was a Far Eastern company founded in 1832 by Scotsmen William Jardine and James Matheson as senior partners. Trafficking opium in Asia, while also trading cotton, tea, silk and a variety of other goods, from its early beginnings in Canton (modern day Guangzhou), in 1844 the firm established its head office in the new British colony of Hong Kong then proceeded to expand all along the China Coast.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Jardine, Matheson & Co. had become the largest of the foreign trading companies in the Far East[1] and had expanded its activities into sectors including shipping, cotton mills and railway construction.

Further growth occurred in the early decades of the twentieth century with new cold storage, packing and brewing businesses while the firm also became the largest cotton spinner in Shanghai.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949, doing business in the country became increasingly problematic. As a result, foreign businesses gradually withdrew from the mainland with Jardines leaving in 1954 to reconsolidate its business in Hong Kong. The firm would not return to mainland China until 1979, following the reform and opening up of the country.[2]

Background

The British and other nations had traded informally with China since the beginning of the seventeenth century.[3] Chinese silk and tea gradually became popular in Britain, but imperial China had little need for British manufactured imports such as woollens.[4] Concerned at what they saw as the encroachment of "barbarians" in their Celestial Kingdom, successive Chinese emperors issued numerous edicts restricting trade with foreigners under what was known as the Canton System.[5] From the middle of the eighteenth century merchants were restricted to an area of Canton on the south China coast, where they were permitted to trade with a group of Chinese merchants known as the Cohong who operated from Thirteen Factories located on the banks of the Pearl River.[6] One of the commodities that the Chinese merchants were interested in buying was opium – considered to have been "the world's most valuable single commodity trade of the nineteenth century".[7] Trade in the drug was controlled by the East India Company, who had been granted a monopoly by the British crown in 1773 giving them sole access to the opium of Bengal[8] although independent traders could still obtain supplies in Malwa, India.[9] However, opium imports were banned in China as reaffirmed by a 1796 edict issued by the Jiaqing Emperor[10] and the only way that the drug could enter the country was if it was smuggled in. At the time, opium was legal and considered relatively safe in the West.[11] As a result, the trade hungry British Empire considered China's refusal to allow imports of the drug an affront to their principles of free trade[11] espoused by Adam Smith and other leading thinkers of the day.

Early history

William Jardine was born in 1784 in the south west of Scotland [12] and graduated from Edinburgh University with a degree in medicine. In 1803, at the age of 19, he became a surgeon on the ships of the British East India Company working the trading routes between London, China and India; a position he held for the next 14 years. As a senior ship's officer, Jardine was allocated an amount of cargo space equal to two chests which he could use to conduct his own business. Using this space, the doctor soon discovered that trading opium was more profitable than practicing medicine. It was during these early days that Jardine found himself on board a ship captured by the French with all its cargo seized. Despite this setback, a trading partnership formed at the time by Jardine with a fellow passenger, a Parsee Indian called Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy, would endure for many years.

In Canton, Jardine met a naturalised Briton of Huguenot extraction named Charles Magniac, brother of Hollingworth Magniac, both of whom would later partner with the Scotsman. Jardine learned that there were ways by which to a small extent the monopoly of the East India Company could be circumvented so in 1819 Jardine left his first employers and began the process of establishing his own private firm.[13] In 1822, he set up in Canton as a free merchant and later, in 1828, joined the established firm of Magniac & Co,[14] which was the forerunner to Jardine Matheson & Co.

James Matheson was born in 1796 in the far north of mainland Scotland and also attended Edinburgh University. He began work in 1815 as a free merchant in Calcutta at his uncle's Agency House, Mackintosh & Co.,[15] trading goods and services between different markets and communities. One day his uncle entrusted him with a letter to be delivered to the captain of a soon-to-depart British vessel. Matheson forgot to deliver the missive and the vessel sailed without it. Incensed at his nephew's negligence, the uncle suggested that young James might be better off back in England. He took his uncle at his word and went to engage a passage back home. Instead, on the advice of an old sea captain, Matheson went to Canton. Here he became an independent merchant acting as agent for firms engaged in the rapidly expanding Indian export market. He then entered into a partnership, known as Yrissari & Co, which quickly became one of the five principal Agency Houses in China at the time, branching out into trade with many different countries. After Francis Xavier de Yrissari's death, Matheson wound up the firm's affairs and closed shop. Yrissari, leaving no heir, had willed all his shares in the firm to Matheson. This created the perfect opportunity for Matheson to join in commerce with Jardine. Matheson proved a perfect partner for Jardine. James Matheson and his nephew, Alexander Matheson, joined the firm Magniac and Co. in 1827, but their association was not officially advertised until 1 January 1828.[16][17] Jardine was known as the planner, the tough negotiator and strategist of the firm and Matheson was known as the organisation man, who handled the firm's correspondence, and other complex articles including legal affairs. Matheson was known to be behind many of the company's innovative practices. The two men were a study in contrasts, Jardine being tall, lean and trim while Matheson was short and slightly portly. Matheson had the advantage of coming from a family with social and economic means, while Jardine came from a much more humble background. Jardine was tough, serious, detail-oriented and reserved while Matheson was creative, outspoken and jovial. Jardine was known to work long hours and was extremely business-minded, while Matheson enjoyed the arts and was known for his eloquence. William C. Hunter, a contemporary of Jardine who worked for the American firm Russell & Co., wrote of him, "He was a gentleman of great strength of character and of unbounded generosity." Hunter's description of Matheson was, "He was a gentleman of great suavity of manner and the impersonation of benevolence." But there were similarities in both men. Jardine and Matheson were second sons, possibly explaining their drive and character. Both men were hardworking, driven and single-minded in their pursuit of wealth.

The private firm of Jardine, Matheson & Co.

For a long time the East India Company had been growing increasingly unpopular in Britain because of its monopoly on Far Eastern trade. Following their independence in 1776, American merchants established a flourishing tea trade with China, leading many people to question the company's continued monopoly.[18] Further, certain high-handed methods used by the East India Company in dealing with competitors aroused the moral indignation of the British at home while anybody that sought to enter the market and bring competition to the company was labelled a privateer – "a pirate" for which the penalty was "death without the benefit of clergy."[19]

Occasionally, free traders did manage to secure a license from the company to engage in the "country trade," usually with India, but never with Britain. Other free traders, called "interlopers"[20] who competed with the Company ran the risk of having their cargoes seized by the company's navy of armed Indiamen before they were hanged.

There was one method available by which a Briton could establish a business on the East India Company's preserves. He could accept the consulship of a foreign country and register under its laws. This method, first used by the Scot's born seaman John Reid, was employed by Jardine to establish himself in Canton. He followed in the footsteps of Magniac, who had obtained an appointment from the King of Prussia as Vice-Consul under his brother Charles, and became the Danish Consul.[21] On this basis the partners had nothing to fear from the company and over time relations between the firm and the East India Company seemed to become amicable. It is recorded that when ships of the East India Company were detained outside the harbour by the authorities, Jardine offered his services "without fee or reward." These services saved the East India Company a considerable sum of money and earned Jardine the company's gratitude.

The earlier activities of Jardine, Matheson, Beale and Magniac made an important contribution to the 1834 termination of the East India Company's monopoly in China[22] whereupon Jardine, Matheson & Co. took this opportunity to fill the vacuum left by the company's departure. That year the firm sent the first private shipments of "Jardines' Pickwick tea mixture",[23] a blend of Chinese teas, from Whampoa aboard the firm's clipper Sarah bound for the docks of Glasgow, Falmouth, Hull and Liverpool, England. Jardine Matheson then began its transformation from a major commercial agent of the East India Company into the largest British trading hong (洋行), or firm, in Asia. William Jardine was now being referred to by the other traders as "Tai-pan", a Chinese colloquial title meaning 'Great Manager'. In a thunderous tribute to Jardine, Matheson wrote, "I am sure none can be more zealous in your service." Jardine succeeded in capturing much of the East India Company's old market supported by its fleet of fast, elegant tea clippers that could out-sail most competitors to be the first to reach consumer markets. These included the Sylph, which set an unbroken speed record by sailing from Calcutta to Macao in 17 days, 17 hours.[24][25] Jardines was also the first company to engage an official 'tea taster' in China to ensure they had a greater understanding of the different varieties of tea, thus enabling them to command the best prices.

Expansion

In the early years of the 19th century both Jardine and Matheson went into partnership with Magniac, who subsequently retired to England in 1828. In 1832, two years before the East India Company lost its monopoly over British trade with China, the partnership was restructured as Jardine Matheson and Company[26] with William Jardine, James Matheson, Alexander Matheson, Jardine's nephew Andrew Jardine, Matheson's nephew Hugh Matheson, John Abel Smith, Henry Wright and Hollingworth Magniac as its first partners. The firm later adopted the Chinese name "Ewo" (怡和洋行),[27] meaning "Happy Harmony" and taken from the former well-regarded Ewo hong run by Howqua as one of Canton's Thirteen Factories.[28] By 1830, the enemies of the East India Company had begun to triumph, and its hold on trade with the East had noticeably weakened with Jardine Matheson by then controlling around half of China's foreign trade.[29]: 32

During the mid-1830s, the China trade became more difficult due to increased controls by the Chinese government to halt the worsening outflow of silver. This trade imbalance arose because Chinese imports of opium exceeded exports of tea and silk.[30] A rush to participate in the fast developing China trade, which was initially centred on tea, had begun when the East India Company monopoly ended in 1834. From the middle of the seventeenth century this drink had been growing in popularity in Britain and the British colonies, but the trade in teas was far from simple. The British crown charged duty of five shillings per pound (0.45 kg) regardless of the quality, which meant that even the cheapest variety available cost seven shillings per pound – almost a whole week's wages for a labourer.[31] This punitive level of taxation meant that huge profits were available, which gave rise to widespread smuggling to avoid the payment of duty. To profit in the China trade participants had to be ahead of all competition, both legitimate and otherwise. Each year, fast ships from Britain, Europe, and America lay ready at the Chinese ports to load the first of the new season's teas. The ships raced home with their precious cargoes, each attempting to be the first to reach the consumer markets, thereby obtaining the premium prices offered for the early deliveries.

Nevertheless, William Jardine wanted to expand the opium trade in China and in 1834, in conjunction with Lord Napier, Chief Superintendent of Trade representing the British Empire, tried unsuccessfully to negotiate with the Chinese officials in Canton. The Chinese Viceroy ordered the Canton offices where Napier was staying to be blockaded and the inhabitants including Napier to be held hostages. Lord Napier, a broken and humiliated man, was allowed to return to Macao by land and not by ship as requested. Struck down by a fever, he died a few days later.[32]

Following this debacle, William Jardine saw an opportunity to convince the British government to use force to further open trade. In early 1835 he ordered James Matheson to leave for Britain to persuade the Government to take strong action in pursuit of this end. Matheson accompanied Napier's widow to England using an eye-infection as an excuse to return home. On arrival, he travelled extensively and held meetings both for government and trade purposes to gather support for a war with China. In some ways unsuccessful in his mission, on being brushed aside by the "Iron Duke" (Duke of Wellington), the then British Foreign Secretary, he reported bitterly to Jardine of being insulted by an arrogant and stupid man, but nevertheless his activities and widespread lobbying in several forums including Parliament bore the seeds that would eventually lead to war. Matheson returned to China in 1836 to prepare to take over the firm as William Jardine got ready to begin his temporarily delayed retirement. Jardine left Canton on 26 January 1839 for Britain, ostensibly to retire but in actuality to continue Matheson's lobbying work.

The Qing Daoguang Emperor, pleased to hear of Jardine's departure, then proceeded to appoint a special Commissioner, Lin Zexu, to stop the opium trade altogether,[33] at that time centred on Canton. Lin commented, "The Iron-headed Old Rat, the sly and cunning ring-leader of the opium smugglers has left for The Land of Mist, of fear from the Middle Kingdom's wrath." The commissioner then ordered the surrender of all opium and the arrest of opium trader Lancelot Dent,[34] the head of Jardine Matheson rival Dent & Co., which triggered a series of events leading to Lin destroying more than 20,000 chests of opium – a large part of which belonged to Jardines.[35]

Once in London, Jardine's first order of business was to meet with the new Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston who had replaced Wellington. He carried with him a letter of introduction written by Chief Superintendent of trade in Canton Charles Elliot that relayed a few of his credentials to Palmerston. Jardine persuaded Palmerston to wage war on China[36] and provided a comprehensive plan along with detailed maps and strategies, the indemnifications and political demands from China and even the number of troops and warships needed in what was known as the Jardine Paper. War followed and in 1842, the Treaty of Nanking was signed by official representatives of both Britain and China. It allowed the opening of major five major Chinese ports, provided indemnification for the opium destroyed and completed the formal acquisition of the island of Hong Kong, which had been officially taken over as a trading and military base on 26 January 1841, though it had already been used for years as a transhipment point. Trade with China, especially in illegal opium, grew, and so did the firm of Jardine, Matheson and Co, by that time already known as the "Princely Hong"[37] for its status as the largest British trading firm in East Asia.

In the 1840s, the Royal Navy leased several carronade-armed clippers from Jardine, Matheson & Co. in 1840 to supplement the steamships it used against Qing dynasty China during the First Opium War.[38]: 12

Jardines had 19 inter-continental clippers by 1841, complemented by hundreds of smaller lorchas and other craft used for coastal and upriver smuggling. As well as smuggling opium into China, Jardines traded sugar and spices from the Philippines, exported Chinese tea and silk to England, acted as cargo factors and insurance agents, rented out dockyard facilities and warehouse space as well as financed trade.[30]

Hong Kong is an island at the mouth of the Pearl River, about 90 miles (140 km) from Canton separated from the mainland of Kowloon by a strip of water which at the narrowest point is only 440 yards (400 m) wide. As late as 1840, the island seemed to have no potential development value. Lying just below the Tropic of Cancer, its climate was considered hot, humid, and unhealthy. In area the island is less than 30 square miles (78 km2), and rises steeply from the water. Before westerners arrived, the total land and water population of around 5,000 fisherfolk and quarrymen[39] lived along the eastern and southern shores. It was also suspected that pirates used the island as a hiding place. Prima facie, the only thing to recommend the island was its natural deep-water harbour. "Hong Kong" came from the Cantonese Heung Gawng (香港) meaning "fragrant harbour" and possibly originated from the scent emanating from the sandalwood incense factories across the water in what is now Shenzhen.[40]

James Matheson had long believed in the future of Hong Kong. In his own words:

"...the advantage of Hongkong would be that the more the Chinese obstructed trade in Canton, the more they would drive trade to the new English settlement. Moreover, Hongkong was admittedly one of the finest harbours in the world.[41]

His enthusiasm was not shared by many of his fellow merchants. Understandably, they preferred not to abandon their comfortable residences on Macau's Praya Grande for the bleak slopes of Hong Kong Island. Bad luck made matters worse for the early Victorian builders. In quick succession, two typhoons and two fires flattened the new settlement while a virulent malaria epidemic almost succeeded in wiping out the island's population. For years, the Canton Press in Macau never lost an opportunity to ridicule and slander the venture. Even Queen Victoria was unimpressed with her new acquisition. Once she wrote a sarcastic note to the King of the Belgians:"--Albert is so much amused at my having got the island of Hongkong, and we think Victoria ought to be called Princess of Hongkong as well as Princess Royal."[42] Despite the setbacks and ridicule, the colony's founders refused to be discouraged.

Hong Kong provided a unique opportunity for Jardine's expansion. On 14 June 1841, the first lots were sold in Hong Kong. At the instigation of James Matheson, three of these, comprising 57,150 square feet (5,309 m2), at East Point were purchased for the sum of 565 Pounds sterling,[43] where Jardines set up one of the first offices in the new colony. Lot No 1 is now the site of the formerly Jardine owned Excelsior hotel, now owned and operated by Mandarin Oriental.[44] Originally, the settlement consisted of hastily constructed mat sheds and wooden buildings with Jardines the first to build a house using brick and stone. It was erected at East Point, and the firm still retains most of the original property. Among the buildings that can still be seen in East Point today is one of the old warehouses with the date 1843 engraved in the stone above the door. and establish their head office in what was officially declared a new British colony in 1843.

Godowns, wharves, offices and houses were also built on the island and facilities established to maintain Jardine's fleet of ships and their crews. At the same time, the company played an active role in the development of the new colony's infrastructure while also providing commercial leadership, credit and services of all kinds to the growing community. In the early years, this included Hong Kong's first ice-making factory, which was later amalgamated with the Dairy Farm Company,[45] the first spinning and weaving factory and the establishment of Hong Kong Tramways. David Jardine, a nephew of William Jardine, was one of the first two unofficial members of the Legislative Council appointed by the Governor in 1850.

The Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1861 with Jardine's 7th Taipan Alexander Perceval, a relative of James Matheson's wife, as its first chairman.[46]

In 1878 the firm pioneered sugar refining in Hong Kong with the formation of the China Sugar Refinery Co.[47]

There are a number of landmarks that record Jardine's role in the history of the community. In the early days, fevers and plagues were a constant menace to the dwellers in Hong Kong, and, the heat during the summer months was difficult to bear. The directors of the firm pioneered construction of residences on The Peak where living was considered more pleasant and healthy.

"Jardine's Corner"[48] was one such landmark, but the best known location associated with the firm is a hill top known as "Jardine's Lookout". From here, in the days of sail, a watch was kept for the first glimpse of the sails of the firm's clippers coming from India and London. As soon as a vessel was signalled, a fast whaleboat was sent out to collect Jardine's mails. The correspondence was rushed back to the office so that the directors could have the first possible information on the world's markets. Jardine's Bazaar off Jardine's Crescent dates to 1845 and is one of the oldest shopping streets in Hong Kong.[49] The Noonday Gun, located opposite the Excelsior Hotel, dates to the 1860s and a time when Jardine's private militia would fire a salvo to salute the arrival of the firm's Taipan in the harbour. This upset the British Navy who insisted that such salutes were reserved for more important people than the head of a trading house. As a penalty Jardines were ordered to fire the gun every day at noon in perpetuity.[50]

Meanwhile, in Shanghai, Jardine, Matheson & Co. were the first to register a building lot on the Bund in 1843 where their first premises at No. 27 were completed in 1851.[51] In the second edition of his Shanghai handbook published in 1920, the Rev. C. B. Darwent estimated that by 1900, the firm's initial investment of £500 in the land was by then worth £1,000,000.[52] Plans for a new Renaissance style building with five stories were drawn up by local architects Stewardson & Spence and work began in 1920. The building was completed in November 1922 and featured a specially designed silk room with exceptional lighting to aid the silk inspectors in their work. Another story was later added to the building and it is today home to the Shanghai Foreign Trade Bureau (外贸大楼).[53]

In 1862, William Keswick bailed out the fledgling Shanghai Race Club to avoid its financial ruin. At its Spring and Autumn meetings, rivalry between the big Hongs such as Jardines and Dents proved intense. The private EWO stables, located next to the Shanghai Race Club, housed 46 ponies in 1922 while the firm had 21 gentlemen riders on its payroll.[52]

New offices were also opened in the trading centres of Fuzhou and Tianjin and, during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the firm underwent a dramatic transformation from an agency house acting for principals to a more diversified business. It traded in a wide variety of imports and exports, promoted railways and other much needed infrastructure projects in China, and founded banks and insurance companies as the country strove towards modernisation.

Diversification and further expansion

There was no practical alternative [to the opium trade] before 1870s. It was not until the firm [Jardines] had been forced from the trade as a major participant that it began proposing the use of capital and techniques for many alternative investments in the treaty ports and in the domestic Chinese economy.[54]

Profits accruing to the firm in the early years were enormous. According to one source, over a ten-year period the amount divided amongst the partners amounted to $15,000,000 – approximately £129,480,000 at 2011 values,[55] "the greater part of which had been accumulated in the opium traffic."[56] Nevertheless, in the face of increasing domestic Chinese competition[57] and a growing anti-opium movement back home in England,[58] in 1872 Jardines formulated an explicit policy ending significant involvement in the opium trade. This move freed up huge amounts of capital, which were then available for investment in new market sectors.[59] In terms of property, Jardines were the only foreign firm to feature on an 1881 list of the eighteen largest land taxpayers in Hong Kong with a bill of HK$4,000 per annum.[60] Such was the influence of the firm that an old joke ran: "Power in Hong Kong resides in the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club; Jardine, Matheson & Co; the Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation; and the Governor – in that order.[61]

Shipping

Shipping played an important role in the firm's expansion. In 1835 the firm had commissioned construction of the first merchant steamer in China, the Jardine. She was a small vessel intended for use as a mail and passenger carrier between Lintin Island, Macau, and Whampoa Dock. However, the Chinese, draconian in their application of the rules relating to foreign vessels, were unhappy about a "fire-ship" steaming up the Canton River. The acting Governor-General of Kwangtung issued an edict warning that she would be fired on if she attempted the trip.[62] On the Jardine's first trial run from Lintin Island the forts on both sides of the Bogue opened fire and she was forced to turn back. The Chinese authorities issued a further warning insisting that the ship leave China. The Jardine in any case needed repairs and was sent to Singapore.[63]

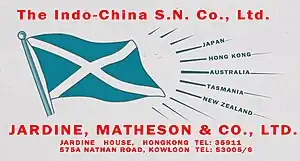

Jardines launched a cargo line from Calcutta in 1855 and began operating on the Yangtze River. The Indo-China Steam Navigation Company Ltd. was formed in 1881,[45] and from then until 1939 maintained a network of ocean, coastal and river shipping services, which were managed by Jardines. In 1938, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the company bought four ships, Haiyuan, Haili, Haichen and Haiheng from the China Merchants' Steam Navigation Company, which were subsequently operated between Hong Kong and Tientsin (modern day Tianjin).[64]

The first ocean-going steamships owned by Jardine's ran chiefly between Calcutta and the Chinese ports. They were fast enough to make the 400-mile (640 km) trip in two days less than rival P & O vessels.

Railways

In spite of firm resistance,[65] Jardines lobbied hard against the government of China for many years to open a railway system. This failed completely,[65] but in 1876 Jardines attempted to move forward on its own by forming the Woosung Road Company to purchase a 10-mile-long road between Shanghai and Wusong for the purpose of converting it first to a mule tramway and then to a narrow-gauge railway, the first in China.[65][66] The first spike was hammered in on 20 January and the line was opened to traffic running six times a day on 3 July. Operations were considered satisfactory until a suicide on the tracks on 3 August 1876 caused the Viceroy of Liangjiang Shen Pao-chen to renew his previous objections.[65] The British authorities ordered the train service to cease operation and the Chinese government announced that it wanted to purchase the line within the year. Jardines were told that as the railway had been built without official approval it could not be defended by the British government and the firm agreed to sell as long as all its costs were covered. Tls. 285,000 were paid in October 1877 for the land, rolling stock and rails which were then dismantled by the government and shipped to Taiwan where they were left to rust on the beach.[67] The line would not be reconstructed until 1898.[65]

Jardines eventually succeeded in winning approval from the Viceroy of Zhili Li Hongzhang for the construction of a mule tramway from the Chinese Engineering and Mining Company's colliery at Tangshan after it was shown the prospective canal would be unable to run the last 6 miles (9.7 km) to the mine. Again ignoring official injunctions against constructing a railroad,[68] the CEMC's engineer Claude W. Kinder first insisted on constructing the tramway at standard gauge and then jury rigged a locomotive from material around the mine.[68] This proved more economical than the mules and the canal's tendency to freeze in the winter – and the coal's strategic importance for the viceroy's Beiyang Fleet – eventually allowed the line's expansion first down the length of the canal and then to major cities like Tianjin. Over two decades, the Kaiping Tramway thus expanded into the China Railway Company,[69] which again was purchased by the Qing government but this time kept on as a paying concern.[65]

In 1898, Jardines and the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Company (HSBC) founded the British and Chinese Corporation (BCC). The civil engineering partnership Sir John Wolfe-Barry and Lt Col Arthur John Barry were appointed Joint Consulting Engineers to the British and Chinese Corporation.[70] The Corporation rebuilt the old Woosung line and then went on to be responsible for much of the development of China's railway system, both in the Yangtze valley and in extensions of the northern Imperial Railways from Shanhaiguan to Newchwang and Mukden.[47]

The Shanghai to Nanjing line was built by Jardines between 1904 and 1908 at a cost of £2.9 million.[71] The BCC was also responsible for the construction of the Kowloon to Canton Railway.

Wharves and real estate

On the initiative of Jardines and Sir Paul Chater, The Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited was formed in 1886. Three years later on 2 March 1889, then Tai-pan James Johnstone Keswick again partnered with Chater to form The Hongkong Land Investment and Agency Company Limited (later Hong Kong Land). The first project undertaken by the new company was the reclamation of an area of 65 acres (260,000 m2) of building land some 250 feet (76 m) wide along a new waterfront road that came to be known as Chater Road.[72] Following an amalgamation of several local wharves in 1875, Jardine, Matheson & Co. were appointed general managers of the Shanghai & Hongkew Wharf Co., Ltd. In 1883, the Old Ningpo Wharf was added, and in 1890 the Pootung Wharf purchased.[73]

Star Ferry

The Star Ferry Company, started by Parsee Dorabjee Nowrojee was bought by the Jardine/Chater controlled Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited in 1898.[74] The company operated steam powered ferries between Hong Kong island and the Kowloon peninsula.

Hong Kong Tramways Ltd.

Jardines helped establish Hong Kong's tram system, which began directly as an electric tram in 1904. The company is now owned jointly by Veolia Transport and The Wharf (Holdings), successor to The Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited.[75]

Insurance

Jardines insurance business, founded as the Canton Insurance Office in 1836 to support its shipping business, began offering underwriting services in many of the places where the company had offices and agencies and, as late as 1860, was still the only insurance company in China. In addition, to cater for clients travelling between Europe and the Far East, the firm had representation along the main steamer routes and at points on the Trans-Siberian Railway, including an agency in Moscow. The Canton Insurance office was later renamed the Lombard Insurance Co.

Jardine Engineering Corporation

Known in Chinese as Yíhé Lóuqì Yǒuxiàn Gōngsī (怡和機器有限公司), literally, "Happy Harmony Tool House", what became Jardine Engineering Corporation (JEC) in 1923 grew out of the period when the business of importing machinery, tools and industrial equipment to support China's development, until then handled by Jardine's Engineering Department, increased to a stage where it could stand alone as a separate company. JEC pioneered ammonia-type air conditioners and new types of heating and sanitation as well as in 1935 providing the vault doors for the new headquarters of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in Hong Kong. JEC also introduced fluorescent strip lighting into Hong Kong in 1940 and in 1949 installed the island's first major industrial air-conditioning plant at Tylers Cotton Mill in the Tokwawan District.[47]

Overseas interests

Jardines was the first foreign trading house to establish a base in Japan when William Keswick, a descendant of William Jardine's sister Jean, was sent there in 1859 following the country's opening up to the outside world. He established an office in Yokohama after acquiring Lot No. 1 in the first land sale. Additional offices subsequently opened in Kobe, Nagasaki and other ports where a large and profitable business was conducted in imports, exports, shipping and insurance.

Jardines also operated in Nairobi in the then British protectorate of Kenya through its Jardine Matheson (East Africa) Ltd. subsidiary and held a majority stake in the South African company Rennies Consolidated Holdings, until it disposed of this 74% stake to Old Mutual in 1983. This was later merged with Safmarine to form Safmarine and Rennies Holdings (Safren).[36]

The firm became so important that for much of the history of the Executive Council of Hong Kong, the business community was represented by 'unofficial members' of the Council who included the head of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation and the Tai-pan of Jardines.[76]

Jardine, Matheson and Co. became a limited company during 1906[47] and until the Second World War was widely referred to as simply the "Firm" or the "Muckle House", muckle being colloquial Scottish for "great".[77]

The EWO companies

From the end of the 19th century, Jardines created a number of new companies using their Chinese name "EWO".[78] The first of these was the EWO Cotton Spinning and Weaving Co. Founded in Shanghai in 1895, it was the first foreign owned cotton mill in China.[79] Two other mills were subsequently started up in Shanghai – the Yangtszepoo Cotton Mill and the Kung Yik Mill. In 1921, these three operations were amalgamated as Ewo Cotton Mills, Ltd. and registered in Hong Kong. Before the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the three mills operated a total of 175,000 cotton spindles and 3,200 looms. In addition the company extended its activities to include the manufacture of waste cotton products, jute materials, and worsted yarns and cloths. The company suffered considerable loss of machinery during the war then in January 1954, Jardines took out adverts in the Hong Kong papers stating that it had "ceased to act as general managers" of EWO Cotton Mills.[80]

The Ewo Yuen Press Packing Company, also known as the Ewo Press Packing Company was established in Shanghai in 1907 and owned jointly by Jardines and a Chinese partner. When the partner retired in 1919, Jardines became sole proprietors of a company with total floor space of 125,000 square feet (11,600 m2), which provided a normal annual output of 40,000 to 50,000 bales – quantities that doubled during peak years. Items packed included raw cotton, cotton yarn, waste silk, wool, hides, goatskins, and other commodities for which press packing for shipment or storage was suitable. The firm also offered rooms to the public for use in the sorting, grading, and storage of all types of cargo. The plant was situated near the mouth of the Soochow Creek, an important transport route at the time providing access to the interior of China or to Shanghai harbour for exports.

In 1920, Jardines established the Ewo Cold Storage Company[78] on the Shanghai river front to manufacture and export powdered eggs. Two or three years later, extensions were made to also permit the processing of liquid and whole eggs. Large quantities of these products were shipped abroad, mainly to the United Kingdom. In the 1920s and 1930s, the export trade in eggs and egg products had become an increasingly important factor in China's economy and immediately prior to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, egg trading was high on the list of leading exports. During the subsequent conflict, although Japanese occupation forces seriously reduced poultry stocks, the situation recovered quickly afterwards as poultry production was chiefly carried out by innumerable small units scattered over vast areas.

In 1935, the company built the EWO Brewery Ltd. in Shanghai.[81] Production commenced in 1936, and EWO Breweries became a public company under Jardines management in 1940. The brewery produced Pilsner and Munich types of beers, which were considered suitable for the Far Eastern climate. The business was sold at a loss in 1954.

Imports and exports

Jardines were a major importer and exporter of all manner of goods prior to the 1937 Japanese invasion of China. Tea and silk ranked high on the list of commodities exported. As long ago as 1801, precursor firms to Jardines had secured the first licences from the East India Company to exports teas to New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land and when the East India Company's trade monopoly was overturned in 1834, the firm lost no time in expanding its tea business. By the 1890s Jardines were exporting large quantities of Keemun. Soochong, Oolong, Gunpowder, and Chun Mee tea. Ocean steamers laden with these cargoes departed from Fuzhou and Taiwan, as well as from the firm's godowns (warehouses) on the Shanghai Bund bound for Europe, Africa, and America. Silk played a prominent role as a commodity during Jardine's first century of operation. Before the Japanese invasion, the firm shipped from Japan to America, France, Switzerland, England, and elsewhere. For many years before war broke out in the late 1930s, the firm operated its own EWO Silk Filature or factory for producing the material. The firm also owned large warehouses in Shanghai, Tientsin, Tsingtao, Hankow, and Hong Kong, which provided access to the products of the cold north, such as wool, furs, soya beans, oils, and oilseeds and bristles as well as the produce of the vast agricultural centre, which included tung and other vegetable oils and oilseeds, egg products, bristles, and beans; and also the marketable yield of the sunny south, its tung oil, aniseed, cassia bark, and ginger. Hongkong and Shanghai were the main import and export centres while branch offices also engaged in these activities on a smaller scale dealing in products from timber to foodstuffs, from textiles to medicines, from metals to fertilizers, and from wines and spirits to cosmetics.

Correspondents

From early on in its history, Jardines did business with a series of "correspondents" in other countries. These companies acted as agents for Jardines and were either independent or partly owned by the firm. In London's Lombard Street, Matheson & Co., Ltd., founded in 1848 as a private house of merchant bankers, became a limited company in 1906 and acted as Jardine's correspondent in London. The company was controlled by Jardines and the Keswick family and was the leading Far Eastern house in London. New York based Balfour, Guthrie & Co., Ltd., a firm founded by three Scotsmen in 1869,[82] looked after the firm's interests in the United States of America. Further correspondents were located in various countries in Africa, Asia and Australia. Jardine's sister company in Calcutta, Jardine Skinner & Co. was established in 1844 by David Jardine of Balgray and John Skinner Steuart, it became a major force in the tea, jute and rubber trades.[83] During the Second World War the company changed its name to Jardine, Henderson, Ltd., later run by John Jardine Paterson.

Jardine Aircraft Maintenance Company (JAMCo)

During the 1940s Jardines opened an Airways Department that provided services as general agents, traffic handlers, and as booking agents. During this period, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) appointed Jardines as their general agents for Hong Kong and China.[84] In Hong Kong, Jardines established JAMCo to provide up-to-date technical and maintenance facilities to the many air lines operating from and through Hong Kong. JAMco was eventually merged with Cathay Pacific's maintenance interests, to form HAECO, on 1 November 1950.[85]

Group structure c. 1938

This is a snapshot of Jardines in c. 1938.[86]

| Wholly owned branches | Date opened | Principal activities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | ||||

| Matheson & Co. | 1848 | Banking, insurance, secretarial services, tea and egg imports. | ||

| China Coast | ||||

| Jardine Matheson | ||||

| Canton | 1832/43 | |||

| Hong Kong | 1844 | Head Office | ||

| Shanghai | 1844 | |||

| Foochow | 1854 | |||

| Peking | 1861 | |||

| Swatow | 1861 | |||

| Tientsin | 1861 | |||

| Hankow | 1860s | |||

| Chung King | 1860s | |||

| Tsingtao | 1860s | |||

| Taipei | 1860s | |||

| Japan | ||||

| Kobe | 1890s | |||

| Principal affiliates | Date started/acquired | Percentage equity | Registered Office location | Principal activities |

| Canton Insurance Office | 1836 | Unknown | Hong Kong | Marine, fire and accident insurance. |

| Hong Kong Fire Insurance | 1868 | Unknown | Hong Kong | Marine, fire and accident insurance. |

| Shanghai & Hong Kew Wharf Co. | 1875 | Unknown | Hong Kong | Shanghai wharves and warehouses. |

| The Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company Limited | 1886 | 7 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong wharves and warehouses. |

| Indo-China Steam Navigation Company Ltd. | 1881 | Unknown | London | Ocean and river shipping. |

| The Hongkong Land Investment and Agency Company Limited | 1889 | 50 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong real estate. |

| Lombard Insurance Co. | 1895 | 100 | UK | Formerly reinsurance, predominantly investments. |

| Star Ferry | 1898 | Unknown | Hong Kong | Ferry services between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. |

| Hong Kong Tramways | 1904 | Unknown | Hong Kong | Electric tram operators. |

| EWO Yuen Press Packing Co. | 1919 | 100 | Hong Kong | Shanghai packing. |

| EWO Cold Storage Co. | 1920 | 100 | Hong Kong | Manufacture of powdered eggs for export. |

| EWO Cotton Mills Ltd. | 1921 | 12 | Hong Kong | Operators of three Shanghai cotton mills. |

| Jardine Engineering Corporation | 1923 | 100 | Hong Kong | Engineering agencies in China. |

| EWO Brewery Ltd. | 1935 | 100 | Hong Kong | Shanghai brewing. |

| Jardine, Matheson & Co. (East Africa) Ltd | 1936 | Unknown | Unknown | Plantations and mines in countries including Kenya. |

War and withdrawal from the Chinese Mainland

Unrest and conflict in China in the 1930s, the Second World War from 1939 to 1945 and the Communist revolution in China in 1949 generated great turmoil in the region and created many challenges for foreign companies such as Jardines to overcome. During the period 1935–1941 the firm had two Taipans – Sir William Johnstone "Tony" Keswick (1903–1990), based at the head office in Shanghai and his younger brother the Hon. Sir John "The Younger" Keswick (1906–1982), in charge of operations in Hong Kong. By 1937, Japan had begun to advance into China and with its entry into the Second World War, the situation worsened for Jardine staff based in the country.

Tony Keswick was shot in the arm by a Japanese official during a 1941 election meeting for the Shanghai Municipal Council held on the Shanghai Racecourse. He escaped major injury but thereafter travelled around the city in a 1925 seven-seater armoured car that had been custom-made for Al Capone.[52] The same year John Keswick, facing internment by the occupying forces, left following Hong Kong's surrender to the invading Japanese on Christmas Day 1941. He managed to escape to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where he served on the staff of Earl Mountbatten of Burma.[36] Both brothers worked clandestinely as senior operatives for British Intelligence throughout the war.[52][87]

Many of Jardines' staff were interned in camps,[88] while others were exiled to Macau, mainland China and elsewhere. Local Chinese staff struggled to survive under Japanese occupation, but several risked their lives to help and support their imprisoned colleagues at great personal risk to themselves.

When the war ended, a handful of emaciated staff emerged from the camp at Stanley to thank those who had helped them, and to celebrate their freedom by re-opening Jardines' offices in Hong Kong as soon as they could. In Shanghai too, the released internees returned to work almost immediately.

Following the end of hostilities in 1945, the British resumed control of Hong Kong and John Keswick returned to oversee the rebuilding of the firm's facilities that had been damaged during the conflict. In Shanghai he attempted to work with the Communists after capitalists were invited to help rebuild the economy. Believing that they would be more orderly and less corrupt than the Nationalists, Keswick argued for British recognition of the new government, and even attempted to run his company's ships past Nationalist blockades.[89] Keswick believed that the heavy taxation implemented by the Communist regime was not "anti-foreignism" but an indication of the need for money to maintain a large army and a new government.[90] As well high taxes, a number of foreign firms including Jardines were expected to buy Red "victory" bonds" that would make an overall contribution of $400,000 to the government's coffers. After protests, this requirement was withdrawn by officials on the grounds that "the tax and bond sales commission had no authority to deal with foreigners."[91]

By 1949 although the firm employed 20,000 people,[47] it became increasingly difficult to conduct business in the new People's Republic of China and by the end of 1954, Jardines had either sold, moved or closed down all its operations in mainland China, writing off millions of dollars in the process. As Time magazine reported:

So ended trading in China of the firm with the biggest British investment east of Suez.[80]

Post-war restructuring

Jardine's Hong Kong operations faced their first post-war challenge as a result of having to comply with the British trade embargo placed against China during the 1950–1953 Korean War.[92] Nevertheless, between 1950 and 1980 the firm underwent another period of dramatic transformation. Just as the nineteenth century had brought change with industrialisation, the decades following the Second World War brought a new period of expansion as Jardines sought out new markets to replace those lost in China. When the Korean War ended in 1953, the firm continued to trade with China through the annual Canton Fair, at which approximately half the country's international trade was conducted through the seven official Chinese state trading corporations.[36]

In 1954, Jardines expanded into Southeast Asia through an investment in Henry Waugh and Co, which had operations in Malaya, Singapore, Thailand and Borneo.

The first formal Reports and Accounts were issued in 1955

In the late 1950s, with support from three banks in London, John and Tony Keswick purchased the last Jardine family interests in the company. After its listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 1961,[93] the firm acquired controlling interests in the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company and Henry Waugh Ltd. as well as established the Australian-based Dominion Far East Line shipping company.[36]

In 1956, John Keswick returned to England to direct the family estate, appointing Michael Young-Herries in his place as manager of operations in Hong Kong.

1960–1970

Jardine, Matheson and Co. offered its shares to the public in 1961 during the stewardship of Tai-pan Sir Hugh Barton, an offer that was oversubscribed 56 times. The Keswick family, in consortium with several London-based banks and financial institutions, had bought out the controlling shares of the Buchanan-Jardine family for $84 million in 1959 but subsequently sold most of the shares at the time of the public offering, thereafter retaining only about 10% of the company.[94]

The Hong Kong Land owned Mandarin Oriental Hotel opened in 1963[95] as the first five-star hotel in Hong Kong's financial district, then one year later the firm's subsidiary Dairy Farm acquired the fledgling Wellcome supermarket chain, which has since grown into one of the largest retail operations in Asia.[96]

Although trade with the mainland virtually ceased with the coming of the 1966 Cultural Revolution, Jardines still managed to sell six Vickers Viscount passenger aircraft to the Chinese Government during this period.[36]

Representative offices were established in Australia in 1963 and in Jakarta in 1967.

1970–1980

In 1970, Asia's first merchant bank, Jardine Fleming, opened for business reflecting the greater sophistication of Asia's financial markets and the increasing personal wealth of individuals, particularly those in Hong Kong.

A 1972 attempt by the Keswick family to install Henry Keswick as chairman met with considerable resistance from supporters of then managing director David Newbigging. However, with the support of institutional investors in London, the Keswicks won the day. Henry was named senior managing director and his father John became chairman, thereby ensuring that the family retained control of Jardines.[36]

Jardines opened the Excelsior hotel in Hong Kong that same year on the site of the original Lot No. 1.[97] purchased by James Matheson more than 120 years before.

Henry Keswick arranged a complete buyout of Reunion Properties, a large real estate firm based in London in 1973, a takeover financed by the creation of an additional seven per cent of Jardine Matheson equity. As a result of the acquisition, the company's assets nearly doubled. In the same year, Henry Keswick also oversaw the acquisition of Theo H. Davies & Company, a large trading company active in the Philippines and Hawaii that controlled 36,000 acres of sugar plantations.[36] World sugar prices rose dramatically a few months after the company was purchased by Jardines as a result of the 1973 oil crisis, netting the company substantial gains.

Hong Kong's building boom presented another opportunity, which Jardines seized with its acquisition in 1975 of leading construction and civil engineering group Gammon Construction.[2] Likewise in the same year, recognising that there would be demand for quality cars among the increasingly affluent population, the company diversified into the luxury car market by acquiring Zung Fu Motors, which held the distribution rights for Mercedes-Benz vehicles in Hong Kong.

The successful bid by Li Ka-shing owned Cheung Kong Holdings for development sites above the Central and Admiralty MTR stations in 1977 was the first challenge to the Jardine owned Hongkong Land as the premier property developer in Hong Kong.

By 1979, the company employed 50,000 people worldwide.[29]: 156

In 1979, Jardines re-established its presence in mainland China after an absence of more than 25 years with the opening of one of the first foreign representative offices in Beijing, followed by Shanghai and Guangzhou. A year later Maxim's Catering, in which Dairy Farm holds a 50% interest, established the Beijing Air Catering Company Ltd, the first foreign joint venture in mainland China since the start of the 'open door' policy.[98] Jardine Schindler followed as the first industrial joint venture.[99]

That same year, Jardine also entered into a joint venture with advertising giant McCann Erickson to form McCann Erickson Jardine (China) Ltd. The new company's remit was to handle advertising for Western corporations in China as well as advertising in the West for Chinese government-owned foreign-trade corporations and other organisations.[100]

During this decade Jardines also expanded their insurance interests with acquisitions in the United Kingdom and the United States laying the groundwork for the foundation of Jardine Insurance Brokers.[2]

1980–1990

By 1980 the firm had operations in southern Africa, Australia, China, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, as well as the United States, and employed 37,000 people.[47] During the following decade, Jardines continued to develop its portfolio of businesses. It expanded its motor interests to the United Kingdom, opened Hong Kong's first branded convenience store under the 7-Eleven franchise, acquired the Pizza Hut and IKEA franchises in Hong Kong and Taiwan and set up a joint venture with Mercedes-Benz in Southern China. Jardine Pacific was also established to bring together the Group's trading and services operations in the region and create larger business units.

In late 1980, an unknown party began buying up shares in Jardines. Many observers suspected that either Li Ka-shing or Sir Y K Pao, working alone or together, was attempting to purchase a large enough share in Jardine Matheson to win control of Hongkong Land. In November that year, then Taipan David Newbigging restructured Jardine Matheson and Hongkong Land by increasing their interests in each other and making it impossible for any party to gain control of either company. As a result, however, both companies incurred significant debt.[36] The costs of fighting off Li Ka-Shing and Sir YK Pao forced Jardines to sell its interests in Reunion Properties.

Jardines marked its 150th anniversary in 1982 by setting up the Jardine Foundation, an educational trust offering Jardine Scholarships to students from the Southeast Asia region to attend Oxford and Cambridge universities. The Jardine Ambassadors Programme was also launched to give young group executives in Hong Kong an opportunity to help the community.

Simon Keswick took over as Taipan in 1983 and quickly moved to reduce the firm's debt by disposing of their interest in the South African-based Rennies Consolidated Holdings. He also implemented a new, decentralised management system with separate divisions responsible for Hong Kong, International and China respectively.

In 1984, Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited ('JMH') was formed as the Group's new holding company incorporated in Bermuda, a British overseas territory.[101] This was done to ensure that the company would be under British law under a different takeover code.[101] Two years later Dairy Farm and Mandarin Oriental were listed in Hong Kong. Jardine Strategic was incorporated to hold stakes in a number of group companies.

In March 1988, Simon Keswick announced that he would step down.[102] He was succeeded by Brian M. Powers, an American investment banker who became the first non-British Tai-pan of Jardines.[103] The appointment caused concern among members of the company's more traditional Scottish establishment but Simon Keswick, who had reversed the company's decline, defended his choice of Powers, explaining that Jardine Matheson was now an international company with Hong Kong interests (not vice versa) and that Powers was best qualified to manage the affairs of such a firm. Subsequently, Powers successfully defended the firm against successive takeover bids by Sir Y K Pao and Li Ka-shing working together with the mainland's state-owned China International Trust & Investment Corp. (CITIC) by splitting the group into two interlocking corporate halves, Jardine Matheson and Jardine Strategic, making them virtually takeover-proof.[104] The raiders subsequently signed a pledge that they would not try another attack on any Jardines firm for seven years.[105]

1990–2000

At the beginning of the 1990s, Jardine Matheson Holdings and four other listed group companies arranged primary share listings on the London Stock Exchange in addition to their Hong Kong listings. In 1994, Jardine Matheson asked Hong Kong's Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) for an exemption from the takeover and mergers code,[106] in order to give the company greater security if Chinese parties attempted a hostile takeover of its listed companies after Hong Kong's 1997 handover from British to Chinese sovereignty. However, the SFC refused and so Jardine firm delisted from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (Hang Seng Index) in 1994 under the tenure of Alasdair Morrison and placed its primary listing in London.[107] Officials in the People's Republic of China (PRC) regarded the delisting as a rebuke to the future of Hong Kong and the government of PRC. This caused trouble when Jardine Matheson attempted to participate in the Container Terminal 9 project but the group's business interests continued to be managed from Hong Kong and the East Asian focus of its business carried on as before.

In 1996, Jardine Fleming was ordered to pay $20.3 million to three investors for alleged abusive and unsupervised securities allocation practices by Colin Armstrong, head of asset management.[108]

The 1997 Asian financial crisis severely affected both Robert Fleming, Jardine's partner in the venture and Jardine Fleming itself. Robert Fleming was forced to approve massive lay offs in late 1998. The firm restructured in 1999, buying the remaining 50% stake in Jardine Flemings in return for giving Jardine Matheson an 18% stake in Robert Flemings Holdings, which was subsequently sold to Chase Manhattan Bank for £4.4 billion ($7.7 billion) in April 2000.[109]

Other significant developments during this decade included the merging of Jardine Insurance Brokers with Lloyd Thompson to form Jardine Lloyd Thompson, the acquisition of a 16% interest in Singapore blue-chip Cycle & Carriage and Dairy Farm's purchase of a significant stake in Indonesia's leading supermarket group Hero. Mandarin Oriental also embarked on its strategy to double its available rooms and capitalise on its brand.

2000–2010

During the first decade of the 21st Century Jardine Cycle & Carriage acquired an initial 31% stake in Astra International, which has since been increased to just over 50% and a 20% shareholding in Rothschilds Continuation Holdings,[110] which rekindled a relationship that began in 1838.[111] Hongkong Land became a Group subsidiary for the first time following a multi-year programme of steady open market purchases while Jardine Pacific raised its interest in Hong Kong Air Cargo Terminals Limited from 25% to 42%.

In 2002, the Group established MINDSET, a mental health charity spearheaded by Jardine Ambassadors as the central focus of the Group's philanthropic activities. In 2010 it officially opened MINDSET Place, a home for people recovering from the effects of chronic mental illness.[112]

From 2003 onwards, Jardine gradually sold off its various holdings in Theo H. Davies & Co.[113]

Notes

- Dong 2000, p. 6.

- "Jardine Official History 1960–1979". Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "The SEA-China Trade" (PDF). National Library of Singapore. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment". Columbia University. 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Chinese responses to Western Intrusions". Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Tamura 1997, p. 111.

- Wakeman Jnr. 1992, p. 172.

- "EAST INDIA COMPANY FACTORY RECORDS Sources from the British Library, London". Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Farooqui 2005, p. 221.

- Chang 1964.

- "Opium Wars (1839–1842)". Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 18.

- Jardine, Matheson & Co. 1947, p. 11.

- "The East India Company's Abkarry and Pilgrim Taxes: Questions of Public Order and Morality or Revenue?" (PDF). Swedish South Asian Studies Network, Lund University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.p. 20

- Greenberg 2000, p. 39.

- Matheson Connell 2004, p. 7.

- "William Jardine". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- "East India Company". Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- "The Truth about the Boston Tea Party". Portland Independent Media Center. 9 January 2006. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- "EIC Ships Glossary". Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 79.

- University of Cambridge Records of Social and Economic History New Series "China Trade and Empire: Jardine, Matheson & Co. and the Origins of British Rule in Hong Kong, 1827–1843" Alain le Pichon

- "Jardine Matheson in China predates Hong Kong treaty". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 9 April 1998. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Hunt 1999.

- Denis Leigh (January 1974). "Medicine, the City and China". Med Hist. 18 (1): 51–67. doi:10.1017/s0025727300019219. PMC 1081522. PMID 4618583.

- "Jardine Matheson Archive". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- "Early Trading Years (1830–1869)". Jardine Matheson Holdings. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Cheong 1997, p. 122.

- Jones, Geoffrey (2000). Merchants to Multinationals: British Trading Companies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829450-4.

- "William Jardine". Archived from the original on 28 December 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Norwood Pratt, James (June 2007). "Bootleg Tea". Teamuse.com. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "Korea in the Eye of the Tiger: Chief Superintendent of Trade". Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "Pioneers of Modern China". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Chang 1964, p. 190.

- Ward Fay 1976, p. 160.

- Funding Universe: Jardine Matheson History

- Tsang 2007, p. 56.

- Driscoll, Mark W. (2020). The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1121-7.

- Ngo 2002, p. 18.

- "History and Past Governors of Hong Kong". Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Greenberg 2000, p. 214.

- Hayes, James (1984). "Hong Kong Island Before 1841". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 24: 105–142. ISSN 1991-7295.

- "Jardine company website, history 1830–1869". Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "Investor information, Mandarin Hotel, Hong Kong". Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "Jardine Matheson Official Site – History". Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Ngo 2002, p. 128.

- "Jardine Matheson Archives". Archives Hub. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- "Jardine's Corner c. 1931". 24 January 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "Gwulo:Old Hong Kong – Jardine's Bazaar". Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Hong Kong Government website: Noonday Gun". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Lampton & Ji 2002, p. 40.

- "Jardine Matheson Building – built in 1920 (No. 27, The Bund)". Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Shanghai Foreign Trade Bureau (外贸大楼)". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- LeFevour 1974.

- Calculated using the UK National Archives currency converter based on exchange rate of £1=$5 at 1860 values.

- Hastings, H.L. (1863). "The Signs of the Times; Or a Glance at Christendom as it is" (PDF). p. 43 Online version

- "Opium in China". Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- "'Britain's Opium Harvest' The Anti-Opium Movement". Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Meyer 2000, p. 104.

- Ngo 2002, p. 48.

- Ngo 2002, p. 3.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1979). "The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 51 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/241899. S2CID 144141748. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Blue, A.D. (1973). "Early Steamships in China" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 13: 45–57. ISSN 1991-7295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Britons Buy Chinese Ships". Evening Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 6 August 1938. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- Huenemann, Ralph Wm. Harvard East Asian Monographs, Vol. 109. The Dragon and the Iron Horse: the Economics of Railroads in China, 1876–1937, pp. 2 ff. Harvard U. Asia Center, 1984. ISBN 0-674-21535-4. Accessed 14 October 2011.

- Crush 1999.

- Pong, David (1973). "Confucian Patriotism and the Destruction of the Woosung Railway, 1877". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 7 (4): 647–676. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00005333. S2CID 202928323.

- Kinder, Claude Wm. "Railways and Collieries of North China" Minutes of Proceedings, Institution of Civil Engineers, Vol. CIII, 1890/91, Paper No.2474.

- Earnshaw 2008.

- Frederick Arthur Crisp Visitation of England and Wales, Volume 14, London (1906)

- Lampton & Ji 2002, p. 63.

- Gwulo: New Oriental Building

- Jardine, Matheson & Co. 1947, p. 29.

- Eric Cavaliero, Star of the harbour Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Standard, 6 February 1997

- "Warf Transport, Veolia Transport Form Partnership to Run Hong Kong Tramways" (PDF). 7 April 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Ingrams, Harold, Hong Kong (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London: 1952), p. 231.

- Wright 1908, p. 211.

- "Jardine Official History". Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Tales of Old Shanghai – Cotton Mills". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- CHINA: Road to Disillusion, Time, 8 February 1954

- Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 262.

- "Early Advertising of the West". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Alasdair Steven, Sir John Jardine Paterson (obituary), in The Scotsman dated 5 April 2000

- Jardine Aviation Services history Archived 12 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "HAECO Official History". Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Sources: Jardine Matheson Archive, Cambridge University Library (UK), Le Fevour, Edward Western Enterprise in Late Ch'ing China (1968) Cambridge, Mass., East Africa Research Center.

- Aldrich 2000, p. 7.

- Keswick & Weatherall 2008, p. 59.

- Schenk 2002.

- Thompson, Thomas N. (1979). "China's Nationalization of Foreign Firms: The Politics of Hostage Capitalism, 1949–1957". 6 (27). School of Law, University of Maryland: 18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Reds Back Down on Bond Sales". Reading Eagle, Pennsylvania, US. Associated Press. 4 April 1950. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Ruthven 2008, p. 295.

- "Jardine Matheson Archives". Archives Hub. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Matheson Connell 2004, p. 61.

- "Story of a Classic – The Mandarin Oriental, Hong Kong". Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "Hong Kong: Wellcome supermarket chain expands". Retail in Asia. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "Jardine Official History". Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "China's first foreign joint venture: The Beijing Air Catering Co. Ltd. (中国首家中外合资企业:北京航空食品有限公司)" (in Chinese). 4 September 2009. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Jardine Schindler website

- New York Times (27 September 1979). "Ad agency establishes joint venture in Peking". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Matheson Connell 2004, p. 168.

- "American to Take Over as 'Taipan' : Brian M. Powers Gets Coveted Spot at Hong Kong Firm". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 12 April 1988. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Nicholas D. Kristof (21 June 1987). "Jardine Matheson's Heir-elect: Brian M. Powers; An Asian Trading Empire Picks an American 'Tai-Pan'". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- William Kay (20 June 2001). "China House rides the economic dragon". The Independent, UK. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "The Superman of Hong Kong". AsiaNow.com. November 2000. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "Let's level the playing field for listed firms". Straits Times, Singapore. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Remembrance of (bad) things past Wall Street Journal, 22 May 2009

- 30, 1996 "Jardine Fleming To Pay Fine". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - Simon Bain (12 April 2000). "Robert Fleming sold in £5 billion deal". The Herald, Scotland.

- Ian Griffiths (2005). "Sale of Rothschild stake secures bank's treasured independence". The Guardian.

- James Moore (23 June 2005). "Royal & Sun Alliance cuts its ties with the Rothschilds". The Daily Telegraph, UK. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- "Speech by DSW at the Prize Giving Ceremony of the Walk Up Jardine House 2010". Department of Social Welfare, Hong Kong Government. 21 March 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Erika Engle (19 October 2003). "Rumored sales of Theo Davies' businesses may signal its end". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

Bibliography

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2000). Intelligence and the War against Japan: Britain, America and the Politics of Secret Service. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64186-1. Online extract

- Blake, Robert (1999). Jardine Matheson – Traders of the Far East. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-82501-1.

- Chang, Hsin-pao (1964). Commissioner Lin and the Opium War. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-393-00521-9.

- Cheong, W.E. (1997). The Hong merchants of Canton: Chinese merchants in Sino-Western trade. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-0361-6.

- Cochran, Sherman (2000). Encountering Chinese Networks: Western, Japanese, and Chinese Corporations in China, 1880–1937. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21625-9.

- Crush, Peter (1999). Woosung Road: The Story of China's First Railway. Hong Kong. ISBN 962-85532-1-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dong, Stella (2000). Shanghai:The Rise and Fall of a Decadent City. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0060934811.

- Earnshaw, Graham (2008). Tales of Old Shanghai. Hong Kong: Earnshaw Books. ISBN 978-988-17-6211-5.

- Farooqui, Amar (2005). Smuggling as Subversion: Colonialism, Indian Merchants, and the Politics of Opium, 1790–1843. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0886-4.

- Greenberg, Michael (2000). Tuck, Patrick J.N. (ed.). British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800–1842. Vol. 9. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18998-5.

- Hunt, Janin (1999). The India-China opium trade in the nineteenth century. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-0715-6. Online version at Google Books

- Jardine, Matheson & Co. (1947). Jardines & the EWO Interests. New York: Charles Phelps.

- Keswick, Maggie; Weatherall, Clara (2008). The thistle and the jade:a celebration of 175 years of Jardine Matheson. Francis Lincoln Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7112-2830-6. Online version at Google books

- Lampton, David M.; Ji, Zhaojin (2002). A History of Modern Shanghai Banking: The Rise and Decline of China's Finance Capitalism. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-1003-5. Online version at Google Books

- LeFevour, Edward (1974). Western Enterprise in Late Ch'ing China: A Selective Survey of Jardine, Matheson & Company's Operations, 1842–1895 in Harvard East Asian Monographs 26. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-95010-8.

- Matheson Connell, Carol (2004). A Business in Risk – Jardine Matheson and the Hong Kong Trading Industry. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98035-1. Online version at Google books

- Meyer, David R. (2000). Hong Kong as a Global Metropolis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64344-3. Online version at Google Books

- Ngo, Tak-Wing, ed. (2002). Hong Kong's History: State and Society Under Colonial Rule. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20305-0. Online version at Google Books

- Ruthven, John Luke (2008). van Dijk, Ruud (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Cold War, Volume 1. Routledge. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-415-97515-5.

- Schenk, Catherine R. (2002). Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre Emergence and Development, 1945–1965. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203183298.ch2. ISBN 978-0-415-20583-2.

- Tamura, Eileen (1997). China: Understanding its past. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1923-1. Online version at Google Books

- Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I. B. Taurus & Company. ISBN 978-1-84511-419-0. Online version at Google Books

- Wakeman Jnr., Frederic (1992). The Canton Trade and the Opium War in John K. Fairbank, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 10, part 1. London. ISBN 0-521-21447-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ward Fay, Peter (1976). The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Kingdom in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by Which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-8078-4714-3.

- Wright, Arnold (1908). Twentieth century impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other treaty ports of China: their history, people, commerce, industries, and resources, Volume 1. Lloyds Greater Britain publishing company.