Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière

Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ maʁi ʁɔlɑ̃ də la platjɛʁ]; 18 February 1734 – 10 November 1793) was a French inspector of manufactures in Lyon and became a leader of the Girondist faction in the French Revolution, largely influenced in this direction by his wife, Marie-Jeanne "Manon" Roland de la Platière. He served as a minister of the interior in King Louis XVI's government in 1792.

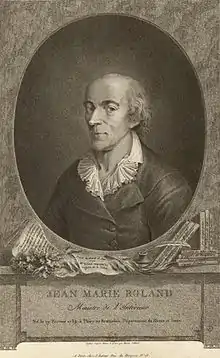

Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière | |

|---|---|

Engraving by Nicolas Colibert, 1792-1793. | |

| Born | 18 February 1734 Thizy, France |

| Died | 10 November 1793 (aged 59) Radepont, France |

| Cause of death | suicide |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | economist |

| Employer | King Louis XVI |

| Known for | leader of Girondist faction |

| Title | Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice |

| Political party | Gironde |

| Opponent | Robespierre |

| Spouse | Jeanne Manon Roland de la Platiere |

| Signature | |

Early life

Roland de la Platière was born and baptized on 18 February 1734 in Thizy, Rhône. He was a studious child, who received a thorough education. At the age of 18 years, Roland was offered the choice of becoming either a businessman or a priest. But he declined both offers and took up studying manufacturing, leading him to the city of Lyons. Two years later, a cousin and inspector of manufactures offered Roland a position in Rouen. He gladly accepted the job. Roland then was transferred to Languedoc, where he became an enthusiastic economist but soon became ill from overwork. He was then offered the less stressful job of lead inspector of Picardy which was the third most important manufacturing province in France in 1781.

Later that year he married Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, better known simply as Madame Roland, the daughter of a Parisian engraver. Madame Roland was just as involved in Jean-Marie's work as he was, editing much of his writing and supporting his political goals. For the first four years of their marriage, Roland continued to live in Picardy and work as a factory inspector. His knowledge of commercial affairs enabled him to contribute articles to the Encyclopédie Méthodique, a three volume encyclopedia of manufacturing and industry, in which, as in all his literary work, he was assisted by his wife.

The Revolution

During the first year of the Revolution, the Rolands moved to Lyon, where their influence grew and their political ambitions became clear. From the beginning of the Revolution, they affiliated with the liberal cause. The articles they contributed to the Courrier de Lyon came to the attention of the Parisian press; although Roland signed them, it was Madame Roland who wrote them. The city then sent Roland to Paris to inform the Constituent Assembly of the critical state of the silk industry and to ask for relief of Lyon's debt. As a result, a correspondence began between Roland, Jacques Pierre Brissot and other supporters of the Revolution, whom he had met in Paris. The Rolands arrived in Paris during February 1791, and remained there until September. They frequented the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, entertaining deputies who later became leading Girondists, and taking an active part in the political landscape. Meanwhile, Madame Roland opened her first salon, helping her husband's name become better known in the capital.

In September 1791, Roland's mission was complete and he returned to Lyon. By then, however, inspectorships of manufacture had been abolished, so the Roland family decided to move and make their new home in Paris. Roland became a member of the Jacobin Club, and their influence continued to grow. Madame Roland's salon becoming the rendezvous of Brissot, Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve, Maximilien Robespierre, and other leaders of the popular movement – especially François Nicolas Leonard Buzot.

When the Girondins assumed power, Roland found himself appointed minister of the interior on 23 March 1792, displaying both his administrative ability and what the Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh Edition, 1911) characterized as "a bourgeois brusqueness". His wife's influence on his declarations of policy was particularly strong in this period: as Roland was ex officio excluded from the Legislative Assembly, these declarations were in writing, and so most prone to exhibit Madame Roland's personal beliefs.

King Louis XVI used his veto power to prevent decrees against émigrés and the non-juring clergy. Madame Roland therefore wrote a letter addressing the royal refusal to sanction the decrees and the role of the king in the state, which her husband addressed and sent to the king. When it remained unanswered, Roland read it aloud in full council and in the king's presence. Judged inconsistent with a minister's position and disrespectful in tone, the incident led to Roland's dismissal. However, he then read the letter to the Assembly, which ordered it printed and circulated. It became a manifesto of dissatisfaction, and the Assembly's subsequent demand that Roland and other dismissed ministers be reinstated eventually led to the king's dethronement.

After the insurrection of 10 August, Roland was reinstated as Interior Minister, but was dismayed by what he saw as the lack of progress made by the Revolution. As a provincial, he opposed the Montagnards who aimed at supremacy not only in Paris but in the government as well. His hostility to the Paris Commune prompted him to propose transferring the government to Blois; and his attacks on Robespierre and his associates made him very unpopular. After failing to seal the armoire de fer (iron chest) found in the Tuileries Palace, containing documents that indicated Louis XVI's relations with corrupt politicians, he was accused of destroying some of the evidence within. Finally, during the trial of the king, he and the Girondists demanded that the sentence should be decided by a poll of the French people rather than the National Convention. Two days after the king's execution, he resigned his office.

Death

Not long after he resigned as minister, the Girondins came under attack and Roland was denounced as well. Roland fled Paris and went into hiding; in his absence, he was sentenced to death. Madame Roland remained in Paris, where she was arrested in June 1793 and executed on 8 November. When Roland learned belatedly of his wife's imminent death, he wandered away from his refuge in Rouen and wrote a few words expressing his horror at the Reign of Terror: "From the moment when I learned that they had murdered my wife, I would no longer remain in a world stained with enemies." He attached the paper to his chest, sat up against a tree, and ran a cane-sword through his heart on the evening of 10 November 1793.[1][2]

See also

References

- Claude Perroud, "Note critique sur les dates de l'exécution de Mme Roland et du suicide de Roland", La Révolution française: revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine, Paris: Société de l'histoire de la Révolution française, t. 22, 1895, pp. 15–26.

- Siân Reynolds, Marriage and Revolution: Monsieur and Madame Roland, Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 287–288.

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Roland, Jean Marie". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. The Britannica

Further reading

- Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (2006)

- Blashfield, Evangeline Wilbour. Manon Phlipon Roland: Early Years (1922) online

- Hanson, Paul R. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution

- Higonnet, Patrice. "The Social and Cultural Antecedents of Revolutionary Discontinuity: Montagnards and Girondins," English Historical Review (1985): 100#396 pp. 513–544 in JSTOR

- Lamartine, Alphonse de. History of the Girondists, Volume I Personal Memoirs of the Patriots of the French Revolution (1847) online free in Kindle edition; Volume 1, Volume 2 | Volume 3

- May, Gita. Madame Roland and the Age of Revolution (1970)

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (1989) excerpt and text search

- Scott, Samuel F. and Barry Rothaus. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution 1789-1799 (1985) Vol. 2 pp 837–41 online

- Sutherland, D.M.G. France 1789–1815. Revolution and Counter-Revolution (2nd ed. 2003) ch 5,

- Tarbell, Ida. Madame Roland, A Biographical Study (1905).

External links

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.