Jesús Malverde

Jesús Malverde (pronounced [xeˈsus malˈβeɾðe] "bad-green Jesus"; born Jesús Juarez Matzo Campos, 15 January 1870–3 May 1909), commonly referred to as the "generous bandit", "angel of the poor",[1] or the "narco-saint", is a folklore hero in the Mexican state of Sinaloa.

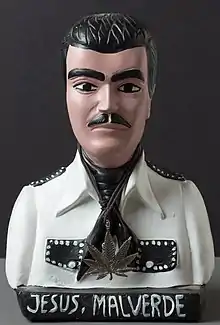

Jesús Malverde | |

|---|---|

Jesús Malverde image | |

| Angel of the Poor, Generous Bandit, The Narco Saint | |

| Born | 15 January 1870 Sinaloa, Mexico |

| Died | 3 May 1909 (age 39) Sinaloa, Mexico |

| Venerated in | Sinaloa; Folk Catholicism |

| Major shrine | Culiacan, Mexico |

| Feast | 3 May |

| Patronage | Mexican drug cartels, drug trafficking, outlaws, bandits, robbers, thieves, smugglers, people in poverty |

He was of Yoreme and Spanish heritage. He is a "Robin Hood" figure who was supposed to have stolen from the rich to give to the poor.[2] He is celebrated as a folk saint by some in Mexico and the United States, particularly among drug traffickers.[3]

History

The existence of Malverde is not historically verified.[4] He is said to have been born Jesús Juárez Mazo Campos, growing up under the rule of Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, whose local supporter Francisco Cañedo ran Sinaloa.

During Malverde's youth, railroads arrived. He witnessed his community undergoing rapid socioeconomic transformation. The profits of hacienda agriculture were enjoyed by the few elite, while the vast majority of the population, the peasantry, faced even greater economic strain.

Jesús Malverde is said to have been a carpenter, tailor, or railway worker.[5] It was not until his parents died of either hunger or a curable disease (depending on the version of the story) that Jesús Malverde began a life of banditry. His nickname Malverde (evil-green) was given by his wealthy victims, deriving from an association between green and misfortune.[2]

According to the mythology of Malverde's life, Cañedo derisively offered Malverde a pardon if he could steal the governor's sword (or, in some versions, his daughter). The bandit succeeded, but this only pushed Cañedo into hunting him down. He is supposed to have died in Sinaloa on 3 May 1909.

Accounts of his death vary. In some versions, he was betrayed and killed by a friend. In others, he was shot or hanged by local police.[2] His body was supposed to have been denied proper burial, being left to rot in public as an example.[1]

Writer Sam Quinones says that there is no evidence that the Malverde of the legend ever lived, and that the story probably emerged by mixing material from the lives of two documented Sinaloan bandits, Heraclio Bernal (1855–1888) and Felipe Bachomo (1883–1916).[6] Bernal was a thief from southern Sinaloa who later became an anti-government rebel. Cañedo offered a reward for his capture, and he was betrayed and killed by former colleagues. Bachomo was an indigenous Indian rebel from northern Sinaloa who was captured and executed.

Cult

Since Malverde's supposed death, he has earned a Robin Hood-type image, making him popular among Sinaloa's poor highland residents. His bones were said to have been unofficially buried by local people, who threw stones onto them, creating a cairn. Throwing a stone onto the bones was thus a sign of respect, and gave the person the right to make a petition to his spirit.[2] His earliest alleged miracles involved the return of lost or stolen property.[6] His shrine is in Culiacán, capital of Sinaloa. Every year on the anniversary of his death, a large party is held at Malverde's shrine. The original shrine was built over in the 1970s, amid much controversy, and a new shrine was built on nearby land.[7] The original site, which became a parking lot, has since been revived as an unofficial shrine, with a cairn and offerings.[8]

The outlaw image has caused him to be adopted as the "patron saint" of the region's illegal drug trade, and the press have thus dubbed him "the narco-saint."[9] However, his intercession is also sought by those with troubles of various kinds, and a number of supposed miracles have been locally attributed to him, including personal healings and blessings.

According to Patricia Price, "Narcotraffickers have strategically used Malverde's image as a 'generous bandit' to spin their own images as Robin Hoods of sorts, merely stealing from rich drug-addicted gringos and giving some of their wealth back to their Sinaloa hometowns, in the form of schools, road improvements, community celebrations."[2]

Spiritual supplies featuring the visage of Jesús Malverde are available in the United States as well as in Mexico. They include candles, anointing oils, incense, sachet powders, bath crystals, soap and lithographed prints suitable for framing.

In culture

A brewery in Guadalajara introduced a new beer, named Malverde, into the northern Mexico market in late 2007.[10]

A likeness of Malverde appears in an episode of the TV show Breaking Bad. In several episodes of its spin-off series, Better Call Saul, Lalo Salamanca wears a necklace that contains a depiction of Malverde.[11] Tony Dalton, the actor who plays Salamanca, explained the meaning of Malverde in a video in which actors review their character's props.[12]

Japanese rapper A-Thug released a mixtape named God MALVERDE in 2017.

In the Netflix series Narcos: Mexico, season 1, episode 7, the character Don Neto relates the story of Jesús Malverde to the man who killed his son before ordering him to be killed. A shrine to Malverde also appears in the intro of the first season of the show.

There is a 2020 Telemundo series featuring Jesús Malverde. It is a dramatized account of different events in his life.

See also

- Chucho el Roto, a Mexican bandit who stole from the rich and shared with the poor

- Gauchito Gil, an Argentinian folk saint who stole from the rich to give to the poor

- Nazario Moreno González, a Mexican drug lord sometimes seen as a folk saint or messiah

- Santa Muerte, a Mexican folk saint associated with drug cartels and criminality

References

- Park, Jungwon; Sujeto Popular entre el Bien y el Mal: Imágenes Dialécticas de "Jesús Malverde". University of Pittsburgh

- Patricia L. Price, Dry Place: Landscapes of Belonging and Exclusion, pp.153–157.

- Penhaul, Karl. "Gang triggerman honored with'Scarface' hat." CNN. 16 April 2009. Retrieved on 16 April 2009.

- grupo reforma

- Kingsbury, Kate and Chesnut, R. Andrew, 2019, "'Narcosaint' Jesús Malverde Miraculously Materializes at Trial of El Chapo Guzman", Global Catholic Review

- Quinones, Sam, True Tales from Another Mexico: The Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino, and the Bronx, UNM Press, 2001, p. 227

- Quinones, Sam, "Jesus Malverde", Frontline, PBS.

- Roig-Franzia, Manuel (22 July 2007). "In the Eerie Twilight, Frenetic Homage To a Potent Symbol". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- "Hidden Powerhouses Underlie Meth's Ugly Spread." The Oregonian/OregonLive. 23 October 2004.

- Castillo, E. Eduardo, Associated Press (7 December 2007). "Mexican company launches beer in honor of unofficial drug saint". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Levin, Matt (3 September 2015). "Meet Jesús Malverde, the patron saint of Mexico's drug cartels". Chron.

- Better Call Saul [@BetterCallSaul] (31 August 2022). "Tony sure did have some iconic props this season. Beef jerky, anyone? #BetterCallSaul t.co/jj7EeyhbPI" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2023 – via Twitter.

Further reading

- Esquivel, Manuel. Jesús Malverde (Jus Ed., Mexico, 2008) ISBN 978-607-412-010-3

- Kingsbury and Chesnut 2019, 'Narcosaint' Jesús Malverde Miraculously Materializes at Trial of El Chapo Guzman by Kingsbury and Chesnut, Global Catholic Review

- Quinones, Sam. True Tales from Another Mexico: the Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino and the Bronx (Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2001)

- Wald, Elijah. Narcocorrido: A Journey into the Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas. ISBN 0-06-050510-9

- "Without God or Law: Narcoculture and belief in Jesús Malverde." James H. Creechan and Jorge de la Herrán-García. 2005. Religious Studies and Theology 24:53.

- Pacific News, "Jesus Malverde-Saint of Mexico's Drug Traffickers May Have Been Bandit Hanged in 1909"

- Portland Mercury, "Our Blessed Saint of Narcotics?"

- Washington Post, "Time Zones: An Hour at the Feet of a Mexican Narco-Saint—In the Eerie Twilight, Frenetic Homage To a Potent Symbol"

- International Herald Tribune, "Mexican Robin Hood figure gains a kind of notoriety abroad"

- Mexican Robin Hood Figure Gains a Kind of Notoriety in U.S. – New York Times

External links

- Photos by Jorge Uzon: The Chapel of Jesus Malverde in Culiacan, Sinaloa