The Jew of Malta

The Jew of Malta (full title: The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Jew of Malta) is a play by Christopher Marlowe, written in 1589 or 1590. The plot primarily revolves around a Maltese Jewish merchant named Barabas. The original story combines religious conflict, intrigue, and revenge, set against a backdrop of the struggle for supremacy between Spain and the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean that takes place on the island of Malta. There has been extensive debate about the play's portrayal of Jews and how Elizabethan audiences would have viewed it.

| The Jew of Malta | |

|---|---|

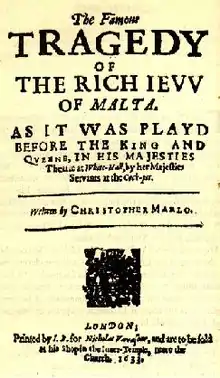

Title page of the 1633 quarto | |

| Written by | Christopher Marlowe |

| Characters | Barabas Abigail Ithamore Ferneze Don Lodowick Don Mathias Katharine |

| Date premiered | c. 1590 |

| Place premiered | London |

| Original language | Early Modern English |

| Subject | Jews, greed, antisemitism, revenge |

| Genre | Revenge tragedy |

| Setting | Malta, 1565 |

Characters

- Machiavel, speaker of the Prologue

- Barabas, a rich Jewish merchant of Malta

- Abigail, his daughter

- Ithamore, his slave

- Ferneze, Governor of Malta

- Don Lodowick, his son

- Don Mathias, Lodowick's friend

- Katharine, Mathias' mother

- Friar Jacomo

- Friar Bernardine

- Abbess

- Selim Calymath, son of the Emperor of Turkey

- Callapine, a bashaw

- Martin del Bosco, Vice Admiral of Spain

- Bellamira, a courtesan

- Pilia-Borsa, her pimp

- Two merchants

- Three Jews

- A messenger

- A slave

- Knights of Malta

- Officers of Malta

- Bashaws serving the Turkish emperor

- Carpenters

- A nun

- Citizens of Malta, Turkish janizaries, guards, attendants, slaves

Summary

The play opens with the character Machiavel, a Senecan ghost based on Niccolò Machiavelli, introducing "the tragedy of a Jew." Machiavel expresses the cynical view that power is amoral, saying "I count religion but a childish toy, / And hold there is no sin but ignorance."[1]

Barabas begins the play in his counting-house. Stripped of all he has for protesting the Governor of Malta's seizure of the wealth of the country's whole Jewish population to pay off the warring Turks, he develops a murderous streak by, with the help of his slave Ithamore, tricking the Governor's son and his friend into fighting over the affections of his daughter, Abigail. When they both die in a duel, he becomes further incensed when Abigail, horrified at what her father has done, runs away to become a Christian nun. In retribution, Barabas then goes on to poison her along with the whole of the nunnery, strangles an old friar (Barnadine) who tries to make him repent for his sins and then frames another friar (Jacomo) for the first friar's murder. After Ithamore falls in love with a prostitute who conspires with her criminal friend to blackmail and expose him (after Ithamore drunkenly tells them everything his master has done), Barabas poisons all three of them. When he is caught, he drinks "of poppy and cold mandrake juice" so that he will be left for dead, and then plots with the enemy Turks to besiege the city.

When at last Barabas is nominated governor by his new allies, he switches sides to the Christians once again. Having devised a trap for the Turks' galley slaves and soldiers in which they will all be demolished by gunpowder, he then sets a trap for the Turkish prince himself and his men, hoping to boil them alive in a hidden cauldron. Just at the key moment, however, the former governor double-crosses him and causes him to fall into his own trap. The play ends with the Christian governor holding the Turkish prince hostage until reparations are paid. Barabas curses them as he burns.[4]

Discussion

Religious scepticism

Despite its focus on Judaism, the play expresses scepticism of religious morality in general. Ferneze, the Christian governor of Malta, first penalises the island's Jews by seizing half of all their assets to pay tribute to the Turkish sultan, then picks on Barabas in particular when he objects, by seizing all his assets. Secondly Ferneze allows admiral Del Bosco to persuade him to break his alliance with the Turks and ally with Spain. Thirdly, at the end of the play Ferneze enthusiastically agrees with Barabas's plan to entrap and assassinate the Turks, but then betrays Barabas by triggering the trapdoor which sends him to his death. Similarly Ithamore, the Muslim slave bought by Barabas, betrays his master to Bellamira the courtesan and Pilia-Borza the thief, and blackmails him, despite Barabas having made him his heir. Thus, Christians, Jews and Muslims are all seen to act contrary to the principles of their faiths – as indeed the prologue by Machiavel hints.

History of Elizabethan antisemitism

Jews had been officially banished from England by King Edward I in 1290 with the Edict of Expulsion, nearly three hundred years before Marlowe wrote The Jew of Malta. They were not openly readmitted to the country until the 1650s. Throughout the period, Jews continued to work and live in London,[5] and it is suggested that, while they were not fully integrated into society, they were generally tolerated and free to go about their business, within their own circles.[6] That said, Elizabethan audiences would generally have had little to no contact with Jews or Judaism in their daily life.[7] Lacking any actual interaction with Jews, English authors, when choosing to write Jewish characters would often resort to utilizing anti-semitic tropes.[7][8] These creations have been the subject of much debate. For instance, some argue that the lack of Jews in England created portrayals different from portrayals of Jewish characters in Europe, where they were permitted to live openly (although constantly in fear of persecution). These differences were, in turn, unique among the marginalized groups of Europe: a kind of double difference marking Jews in England as exceptionally ostracized.[8][9] British author Anthony Julius noted that during this era, as discussion of Jews became more prominent in mainstream discourse, so did plays which contained antisemitic elements.[8][10] Many of the antisemitic tropes in Jewish characters written during this period were also popular among authors on the Continent, coming about during a period of increasing contact amongst the various nations of Europe.[8][11]

These tropes could also have contributed to the popularity of plays such as Marlowe's The Jew of Malta. In 1594 Roderigo López, a Converso and doctor to Queen Elizabeth I, was accused of attempting to poison his mistress and put on trial for treason. Public demands for his execution, many of which were loaded with anti-Semitic tropes, were an important factor in his conviction for attempted murder. His execution coincided with a reperformance of Marlowe's play at the Rose Theatre.[12]

Antisemitism in The Jew of Malta

The Jew of Malta, given the time of its publication, its main character, and the significance of religion throughout the text, is often referenced in discussions about antisemitism. Some of the conversation around antisemitism in The Jew of Malta focuses on authorial intent, the question of whether or not Marlowe intended to promote antisemitism in his work, while other critics focus on how the work is perceived, either by its audience at the time or by modern audiences.

A Marxist critique of The Jew of Malta suggests that Marlowe intended to utilize readily available antisemitic feelings in his audience in a way that made the Jews "incidental" to the social critique he offered. That is, he wished to use antisemitism as a rhetorical tool rather than advocating for it. In this, Marlowe failed, instead producing a work that is, because of its failure to "discredit" the sentiments it toys with, a propagator of antisemitism. Such rhetorical attempts "underestimated the irrationality... fixation...and persistence of anti-Semitism".[7]

Another viewpoint suggests that those who claim to see antisemitism in Marlowe's work often do so more because of what they think they know about the period in which they were written rather than what the texts themselves present. Thomas Cartelli, a professor of English and Film Studies at Muhlenberg College, admits that certain of Barabas' features are troublesome vis-à-vis antisemitism, such as his large and often-referenced nose, but suggests that such surface details are not important. If one looks past the surface, it is argued, the play can be seen as uniting all three religions it represents—Judaism, Islam, and Christianity—by way of their mutual hypocrisy. These examples illustrate, though not fully, the breadth of opinions expressed on the subject.[13]

Authorship

Complicating the accusations of Marlowe's antisemitism, there has been significant scholarly dissension about the authorial nature of the text of the play. These reactions range from suggesting that the text of the play is entirely by Marlowe, but that the beginning was distorted towards the end by the strictures and deadlines of a theater's demands,[5] so that subsequent adaptations and manuscripts have significantly distorted the original text.[14] In particular, observers believe the third, fourth and fifth acts to be written, at least partially, by someone else.[15] Others disagree, pointing out that the steadily building climb of Barabas' sins, culminating with his death by his own plot, to be indicative of a consistent authorial presence.[16]

While the play was entered in the Stationers' Register on 17 May 1594, the earliest surviving edition was printed in 1633 by the bookseller Nicholas Vavasour, under the sponsorship of Thomas Heywood.[17] This edition contains prologues and epilogues written by Heywood for a revival in that year. Heywood is also sometimes thought to have revised the play. Corruption and inconsistencies in the 1633 quarto, particularly in the third, fourth, and fifth acts, may be evidence of revision or alteration of the text.[18]

The Merchant of Venice

Some critics have suggested that the play directly influenced Marlowe's contemporary, William Shakespeare, in the writing of his play The Merchant of Venice (written c. 1596–99).[19] James Shapiro notes that both The Merchant of Venice and The Jew of Malta are works obsessed with the economics of their day, stemming from anxiety around new business practices in the theater, including the bonding of actors to companies. Such bonds would require actors to pay a hefty fee if they performed with other troupes or were otherwise unable to perform. In this way, greed becomes an allegory rather than a characteristic or stereotype.[19]

Others believe that the suggestion of imitation by Shakespeare of Marlowe is overblown, and that not only the two stories are very different, but the principal characters that are often compared, Shylock and Barabas, are themselves profoundly different.[6]

While critics debate whether or not The Jew of Malta was a direct influence, or merely a product of the contemporaneous society that they both were written in, it is noteworthy that Marlowe and Shakespeare were the only two English playwrights of their time to include a Jewish principal character in one of their plays.[6]

Biblical punishment

At the end of the play, Barabas attempts to murder his erstwhile Turkish allies by tricking them into falling through a trap door into a hot cauldron in a pit. In the end, it is Barabas who falls into his own fiery pit and dies a violent death.[4] The method by which Barabas dies has several specific Biblical overtones, and these connections have been acknowledged by scholars.[16] In terms of the specifications for punishment dictated by the Old Testament, it matches the crime in Barabas' case: he is guilty of murder, fraud, and betrayal by a Jew.[16] Secondarily, there is a frequent use in Judaism of a device where a perpetrator is ensnared in his own trap. An example of this includes Haman, in the story of Purim, being hanged on the very gallows he intended for the Jews he wished to murder.[16]

Performance and reception

The Jew of Malta was an immediate success[5] from its first recorded performance at the Rose Theatre in early 1592, when Edward Alleyn played the lead role.[20] The play was subsequently presented by Alleyn's Lord Strange's Men seventeen times between 26 February 1592 and 1 February 1593. It was performed by Sussex's Men on 4 February 1594, and by a combination of Sussex's and Queen Elizabeth's Men on 3 and 8 April 1594. More than a dozen performances by the Admiral's Men occurred between May 1594 and June 1596. (The play apparently belonged to impresario Philip Henslowe, since the cited performances occurred when the companies mentioned were acting for Henslowe.) In 1601 Henslowe's diary notes payments to the Admiral's company for props for a revival of the play.[21]

The play remained popular for the next fifty years, until England's theaters were closed in 1642. In the Caroline era, actor Richard Perkins was noted for his performances as Barabas when the play was revived in 1633 by Queen Henrietta's Men. The title page of the 1633 quarto refers to this revival, performed at the Cockpit Theatre.[22]

The play was revived by Edmund Kean at Drury Lane on 24 April 1818. The script of this performance included additions by S. Penley.[23] It was considered a successful production at the time. However, in an anonymous biography of Kean published seventeen years later, it suggests that the success of the production came from Kean's performance and his addition of a song to the role of Barabas, and that the play itself, on its own, was a failure.[5]

On 2 October 1993, Ian McDiarmid starred as Barabas in a BBC Radio 3 adaptation of the play directed by Michael Fox, with Ken Bones as Machevil and Ferneze, Kathryn Hunt as Abigail, Michael Grandage as Don Lodowick, Neal Swettenham as Don Mathias and Kieran Cunningham as Ithamore.[24]

Footnotes

- N. W. BAWCUTT (1970). "Machiavelli and Marlowe's "The Jew of Malta" in Renaissance Drama". University of Chicago Press: 3. JSTOR 41917055.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/100403.pdf

- "Knights, Memory, and the Siege of 1565: An Exhibition on the 450th Anniversary of the Great Siege of Malta". calameo.com.

- Marlowe, Christopher (1997). Bevington, David (ed.). The Jew of Malta. New York: Manchester University Press.

- Swan, Arthur (1911). "The Jew That Marlowe Drew". The Sewanee Review. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 19: 493.

- Ribner, Irving (Spring 1964). "Marlowe and Shakespeare". Shakespeare Quarterly. 15 (2): 41–53. doi:10.2307/2867874. JSTOR 2867874.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (1978). "Marlowe, Marx, and Anti-Semitism". Critical Inquiry. 5 (2): 291–307. doi:10.1086/447990. S2CID 153818340.

- Lavezzo, Kathy (2013). "Jews in Britain-Medieval to Modern". Philological Quarterly. 92 (1).

- Freedman, Jonathan (1994). The Temple of Culture. University of Nebraska Press. p. 6.

- Julius, Anthony (2010). Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England. Oxford University Press. pp. xxxvi.

- Bale, Anthony (2006). The Jew in the Medieval Book: English Antisemitisms 1350–1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 17.

- Dautch, Aviva (15 March 2016). "A Jewish reading of The Merchant of Venice". The British Library. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Cartelli, Thomas (1988). "Shakespeare's Merchant, Marlowe's Jew: The problem of cultural difference". Shakespeare Studies. 20.

- Maxwell, J.C. (1953). "How Bad Is the Text of 'The Jew of Malta'?". The Modern Language Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 48 (4): 435–438. doi:10.2307/3718657. JSTOR 3718657.

- Babb, Howard S. (1957). "Policy in Marlowe's The Jew of Malta". ELH. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 24 (2): 85–94. doi:10.2307/2871823. JSTOR 2871823.

- Tkazcz, Catherine Brown (May 1988). ""The Jew of Malta" and the Pit". South Atlantic Review. 53, #2 (2): 47–57. doi:10.2307/3199912. JSTOR 3199912.

- Rose, Mark (Spring 1980). "The Jew of Malta. The Revels Plays by Christopher Marlowe and N. W. Bawcutt". Comparative Drama. 14 (1): 87–89. doi:10.1353/cdr.1980.0010. S2CID 194847995.

- Bevington & Rasmussen, pp. xxviii–xxix.

- Shapiro, James (1988). ""Which is the merchant here and which the jew?": Shakespeare and the economics of influence". Shakespeare Studies. 20.

- Lisa Hopkin. Gale Researcher Guide for: Edward II: Sexuality and Politics in Christopher. Gale Learning. p. 5. ISBN 9781535853231.

- Chambers, Vol. 3, pp. 424–5.

- Chambers, Vol. 3, p. 424.

- Frederick Boas, Christopher Marlowe: A biographical and critical study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953), p. 301

- "Sunday Play: The Jew of Malta". 3 October 1993. p. 100 – via BBC Genome.

References

- Bevington, David, and Eric Rasmussen, eds. Doctor Faustus and Other Plays. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-283445-2.

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Marlowe, Christopher. The Jew of Malta. David Bevington, ed. Revels Student Editions. New York, Manchester University Press, 1997.

External links

- The Jew of Malta at Standard Ebooks

- The Jew of Malta – Complete play (plain text) at Project Gutenberg

The Jew of Malta public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Jew of Malta public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Jew of Malta – Complete audio performance, faithful to the text, of Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta (1993)

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "The shock of the Jew" by Carl Miller