Jewish community of Worcester, England

During the Middle Ages there was a small Jewish community in Worcester, a city and county town of Worcestershire in the West Midlands of England that mainly provided money lending services to the non-Jewish citizens. Worcester also hosted a national gathering of England's leading Jews in 1241, to allow the Crown to assess their worth for taxation. The Worcester Bishopric was hostile to the Jewish community in Worcester, commissioning tracts against Jewry, and pushing for segregation of Jews and Christians. During the Second Barons' War, Jews suffered violence and many died in 1255, at the hands of Simon de Montfort's supporters.

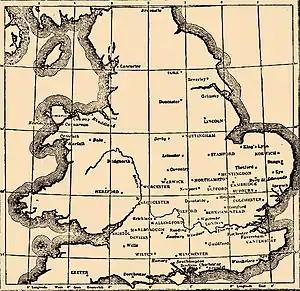

City of Worcester, England | |

|---|---|

City of Worcester, shown within Worcestershire |

Jews were expelled from Worcester in 1275 and most left for Hereford. The former residents suffered the fate of other Jewish communities in the Middle Ages and were finally expelled with the rest of the British Jewry in 1290.

The community was reestablished many centuries later during the Second World War. After the war the community dwindled and the synagogue was closed in 1973.

The Jews in Worcester in the Middle Ages

Worcester, like most important boroughs, contained a Jewry as early as the 12th century.[1]

The first reference to a presence of Jews in Worcester is from 1154 when a few Jewish families are known to have lived there. Presumably they earned their living by providing money-lending services to the local population, as was the case in other English centres.

In 1184 a Jew name Bonefei was fined one mark of gold to the King's court.[2]

A few years later there is evidence of a money lender named Leo the Jew who lent money to the abbot of Pershore. He was imprisoned for a forcible entry into the hospital of Worcester, doubtless in the attempt to make good some legal claim.[2]

Worcester was one of the 26 Jewish centres of these days to have an archa. The archa was an official chest, provided with three locks and seals, in which a counterpart of all deeds and contracts involving Jews was to be deposited in order to preserve the records.

The introduction of archae was part of the reorganization of English Jewry ordered by King Richard I in light of the massacres of Jews that took place in 1189-1190 at, and shortly following, his coronation. These massacres resulted in a heavy loss of Crown revenue partly as a result of Jewish financial records being destroyed by the murderous mob (in order to conceal evidence of debts due to the Jews). The archae were intended to safeguard the royal rights in case of future disorder. All Jewish possessions and credits were to be registered and certain cities were designated to serve as the centres for all future Jewish business operations and the registration of Jewish financial transactions, each such city having an archa. In each centre, a bureau was set up consisting of two reputable Jews and two Christian clerks, under the supervision of a representative of the newly established central authority that became known as the Exchequer of the Jews.

The right of Jews to live in Worcester was expressly confirmed by King Henry III who came to the throne in 1216. There is some evidence that there may have been a Jewish Quarter in the area of Cooken or Coken Street (now Copenhagen Street), in St. Andrew's parish in the city.[3]

The Diocese was notably hostile to the Jewish community in Worcester. Peter of Blois was commissioned by a Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances to write a significant anti-Judaic treatise Against the Perfidy of Jews around 1190.[4][5]

William de Blois, as Bishop of Worcester, imposed particularly strict rules on Jews within the diocese in 1219.[6] As elsewhere in England, Jews were officially compelled to wear square white badges, supposedly representing tabula. In most places, this duty was relinquished so long as fines were paid. In addition to enforcing the church laws on wearing badges. Blois attempted to impose additional restrictions on usury, and wrote to Pope Gregory in 1229 to ask for better enforcement and further, harsher measures. In response, the Papacy demanded that Christians be prevented from working in Jewish homes, "lest temporal profit be preferred to the zeal of Christ", and enforcement of the wearing of badges.[7]

In 1241 Henry III summoned what was later termed a “Jewish parliament” in Worcester. It was however a meeting to assess the potential of the English Jewry for taxation. The result was that Henry afterwards "squeezed the largest tallage of the thirteenth century from his Jewish subjects."[8]

In 1263, during the baronial revolt of Simon de Montfort, the rebel Robert Ferrers, earl of Derby led an attack on Worcester. He allowed his soldiers to sack the city and destroy the Jewish community.[2] Ferrers used this opportunity to remove the titles to his debts by taking the archae.[9] The massacre in Worcester was part of a wider campaign by the De Montforts and their allies in the run up to the Second Barons' War, aimed at undermining Henry III. Simon de Montfort had previously been engaged in a campaign of persecution of Jewish communities in Leicester. A massacre of London's Jewry also took place during the war.

In 1272 Edward I became King of England. On his marriage in 1275 to Eleanor, Edward gave her 'by way of dower’, to the cities of Worcester, Bath and Gloucester together with certain other towns. Edward I issued a writ that 'no Jew may dwell or abide in any of the towns which the queen has for her dower', so the Jews of Worcester were moved to Hereford.[10][11]

The Jews of Worcester were finally expelled from England, as were all other Jews, in 1290.

Reestablishment of the Jewish community in Worcester in 1941

Only 651 years later, in 1941, did the Jewish Chronicle announce the reestablishment of the Jewish community in Worcester.

The community was reestablished to serve evacuees from London and Birmingham as a result of the German bombings of English cities during World War 2. Together with the British Jews, a number of Jewish refugees from Europe had also settled in the city.

The Jewish newcomers to Worcester integrated in the city's economy. One example was the Milore Glove factory that was founded by Emil Rich. He was a refugee from Germany.

The Jewish evacuees and refugees were joined for the duration of the war by some American and Jewish servicemen from other countries who were stationed in the area. Services were held in the city and, as a result of assistance of Rabbi Reuben Rabinowitz from the Central Synagogue in Birmingham, Hebrew classes for the children were inaugurated.[12]

At first services were held in temporary accommodation but a synagogue was consecrated at 2 New Street in March 1943 by the Chief Rabbi of Britain. The opening ceremony was performed by Mr Isaac Wolfson, a well known and successful businessman who lived in Worcester at the time.

The synagogue appointed the Rev J. Rockman as reader and Hebrew teacher. The chairman of the community was Mr J. Zuck. The building incorporated a canteen and social rooms for servicemen and workers. The first barmitzvah, that of Stanley Davis, was held in Worcester in February 1943.

Jewish community in Worcester after World War II

After the end of the war a majority of community returned to their original larger Jewish communities. However, a small nucleus remained continued to support the synagogue, regular services were held and children’s classes were organized.

In 1960, under of the guidance of the then chairman Dr Wolf Hirshow and vice chairman Mr A.J. Berger the members undertook an extensive reconstruction of the building part of which had become unsafe.

Decline of the community

The synagogue continued to function until January 1973. By that time it had become increasingly difficult to obtain a minyan for services and the remaining members decided to vote the community out of existence. One Sefer Torah which had been borrowed from Birmingham in 1940 was returned to its owners, while a second one was donated to a new Israeli community.

References

- Robin R. Mundill (16 May 2002), England's Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 12621290, Cambridge University Press (published 16 May 2002), ISBN 9780521520263, OCLC 49550956, OL 7744058M

- Joe Hillaby, ‘The Worcester Jewry, 1158-1290, Portrait of a Lost Community,’ Transactions of the Worcestershire Archaeological Society, third series, Vol.12, 1990

- Willis-Bund, J W; Page, William, eds. (1924). "The city of Worcester: Introduction and borough". A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 4. London: British History Online. pp. 376–390. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Vincent, Nicholas (1994). "Two Papal Letters on the Wearing of the Jewish Badge, 1221 and 1229". Jewish Historical Studies. 34: 209–24. JSTOR 29779960.

Notes

- , Medieval(Pre-1290)Jewish Communities in the English Midlands - Jewish Communities and Records

- 'The city of Worcester: Introduction and borough', in A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 4, ed. William Page and J W Willis-Bund (London, 1924), pp. 376-390. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/worcs/vol4/pp376-390 [accessed 20 May 2018].

- http://www.worcester.gov.uk/index.php?id=550, History of Worcester in the Middle Ages, Worcester City Council website

- "A treatise addressed to John Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances who held that See, 1194-8." Medieval Sourcebook: Peter of Blois: Against the Perfidy of the Jews , before 1198.

- Bernard Lazare (1903), Antisemitism, its history and causes., New York: The International library publishing co., LCCN 03015369, OCLC 3055229, OL 7137045M

- Vincent (1994), p217

- Vincent (1994), p209

- Mundill 2002, p58 and quotation p60

- Mundill 2002, p42

- http://www.wildolive.co.uk/hereford_history.htm, The Jewish Community in Hereford (England), up to 1290, Wildolive

- Mundill 2002, p23

- http://www.jewishgen.org/JCR-UK/Community/worcester/JC.htm, JCR-UK - References to the Worcester Jewish Community Appearing in the Jewish Chronicle During World War II Compiled by Harold Pollins