Jōdo Shinshū

Jōdo Shinshū (浄土真宗, "The True Essence of the Pure Land Teaching"[1]), also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism. It was founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism in Japan |

|---|

|

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.[2]

History

Shinran (founder)

Shinran (1173–1263) lived during the late Heian to early Kamakura period (1185–1333), a time of turmoil for Japan when the emperor was stripped of political power by the shōguns. Shinran's family had a high rank at the Imperial court in Kyoto, but given the times, many aristocratic families were sending sons off to be Buddhist monks instead of having them participate in the Imperial government. When Shinran was nine (1181), he was sent by his uncle to Mount Hiei, where he was ordained as a śrāmaṇera in the Tendai sect. Over time, Shinran became disillusioned with how Buddhism was practiced, foreseeing a decline in the potency and practicality of the teachings espoused.

Shinran left his role as a dosō ("practice-hall monk") at Mount Hiei and undertook a 100-day retreat at Rokkaku-dō in Kyoto, where he had a dream on the 95th day. In this dream, Prince Shōtoku appeared to him, espousing a pathway to enlightenment through verse. Following the retreat, in 1201, Shinran left Mount Hiei to study under Hōnen for the next six years. Hōnen (1133–1212) another ex-Tendai monk, left the tradition in 1175 to found his own sect, the Jōdo-shū or "Pure Land School". From that time on, Shinran considered himself, even after exile, a devout disciple of Hōnen rather than a founder establishing his own, distinct Pure Land school.

During this period, Hōnen taught the new nembutsu-only practice to many people in Kyoto society and amassed a substantial following but also came under increasing criticism by the Buddhist establishment there. Among his strongest critics was the monk Myōe and the temples of Enryaku-ji and Kōfuku-ji. The latter continued to criticize Hōnen and his followers even after they pledged to behave with good conduct and to not slander other Buddhists.[3]

In 1207, Hōnen's critics at Kōfuku-ji persuaded Emperor Toba II to forbid Hōnen and his teachings after two of Imperial ladies-in-waiting converted to his practices.[3] Hōnen and his followers, among them Shinran, were forced into exile and four of Hōnen's disciples were executed. Shinran was given a lay name, Yoshizane Fujii, by the authorities but called himself Gutoku "Stubble-headed One" instead and moved to Echigo Province (today Niigata Prefecture).[4]

It was during this exile that Shinran cultivated a deeper understanding of his own beliefs based on Hōnen's Pure Land teachings. In 1210 he married Eshinni, the daughter of an Echigo aristocrat. Shinran and Eshinni had several children. His eldest son, Zenran, was alleged to have started a heretical sect of Pure Land Buddhism through claims that he received special teachings from his father. Zenran demanded control of local monto (lay follower groups), but after writing a stern letter of warning, Shinran disowned him in 1256, effectively ending Zenran's legitimacy.

In 1211 the nembutsu ban was lifted and Shinran was pardoned, but by 1212, Hōnen had died in Kyoto. Shinran never saw Hōnen following their exile. In the year of Hōnen's death, Shinran set out for the Kantō region, where he established a substantial following and began committing his ideas to writing. In 1224 he wrote his most significant book, the Kyogyoshinsho ("The True Teaching, Practice, Faith and Attainment of the Pure Land"), which contained excerpts from the Three Pure Land sutras and the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra along with his own commentaries[4] and the writings of the Jodo Shinshu Patriarchs Shinran drew inspiration from.

In 1234, at the age of sixty, Shinran left Kantō for Kyoto (Eshinni stayed in Echigo and she may have outlived Shinran by several years), where he dedicated the rest of his years to writing. It was during this time he wrote the Wasan, a collection of verses summarizing his teachings for his followers to recite.

Shinran's daughter, Kakushinni, came to Kyoto with Shinran, and cared for him in his final years and his mausoleum later became Hongan-ji, "Temple of the Original Vow". Kakushinni was instrumental in preserving Shinran's teachings after his death, and the letters she received and saved from her mother, Eshinni, provide critical biographical information regarding Shinran's earlier life. These letters are currently preserved in the Nishi Hongan temple in Kyoto. Shinran died at the age of 90 in 1263 (technically age 89 by Western reckoning).[4]

Revival and formalization

Following Shinran's death, the lay Shin monto slowly spread through the Kantō and the northeastern seaboard. Shinran's descendants maintained themselves as caretakers of Shinran's gravesite and as Shin teachers, although they continued to be ordained in the Tendai School. Some of Shinran's disciples founded their own schools of Shin Buddhism, such as the Bukko-ji and Kosho-ji, in Kyoto. Early Shin Buddhism did not truly flourish until the time of Rennyo (1415–1499), who was 8th in descent from Shinran. Through his charisma and proselytizing, Shin Buddhism was able to amass a greater following and grow in strength. In the 16th-century, during the Sengoku period the political power of Honganji led to several conflicts between it and the warlord Oda Nobunaga, culminating in a ten-year conflict over the location of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji, which Nobunaga coveted because of its strategic value. So strong did the sect become that in 1602, through mandate of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, the main temple Hongan-ji in Kyoto was broken off into two sects to curb its power. These two sects, the Nishi (Western) Honganji and the Higashi (Eastern) Honganji, exist separately to this day.

During the time of Shinran, followers would gather in informal meeting houses called dojo, and had an informal liturgical structure. However, as time went on, this lack of cohesion and structure caused Jōdo Shinshū to gradually lose its identity as a distinct sect, as people began mixing other Buddhist practices with Shin ritual. One common example was the Mantra of Light popularized by Myōe and Shingon Buddhism. Other Pure Land Buddhist practices, such as the nembutsu odori[5] or "dancing nembutsu" as practiced by the followers of Ippen and the Ji School, may have also been adopted by early Shin Buddhists. Rennyo ended these practices by formalizing much of the Jōdo Shinshū ritual and liturgy, and revived the thinning community at the Honganji temple while asserting newfound political power. Rennyo also proselytized widely among other Pure Land sects and consolidated most of the smaller Shin sects. Today, there are still ten distinct sects of Jōdo Shinshū, Nishi Hongan-ji and Higashi Hongan-ji being the two largest.

Rennyo is generally credited by Shin Buddhists for reversing the stagnation of the early Jōdo Shinshū community, and is considered the "Second Founder" of Jōdo Shinshū. His portrait picture, along with Shinran's, are present on the onaijin (altar area) of most Jōdo Shinshū temples. However, Rennyo has also been criticized by some Shin scholars for his engagement in medieval politics and his alleged divergences from Shinran's original thought. After Rennyo, Shin Buddhism was still persecuted in some regions. Secret Shin groups called kakure nenbutsu would meet in mountain caves to perform chanting and traditional rituals.

Following the unification of Japan during the Edo period, Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism adapted, along with the other Japanese Buddhist schools, into providing memorial and funeral services for its registered members under the Danka system, which was legally required by the Tokugawa shogunate in order to prevent the spread of Christianity in Japan. The danka seido system continues to exist today, although not as strictly as in the premodern period, causing Japanese Buddhism to also be labeled as "Funeral Buddhism" since it became the primary function of Buddhist temples. The Honganji also created an impressive academic tradition, which led to the founding of Ryukoku University in Kyoto and formalized many of the Jōdo Shinshū traditions which are still followed today.

Following the Meiji Restoration and the subsequent persecution of Buddhism (haibutsu kishaku) of the late 1800s due to a revived nationalism and modernization, Jōdo Shinshū managed to survive intact due to the devotion of its monto. During World War II, the Honganji, as with the other Japanese Buddhist schools, was compelled to support the policies of the military government and the cult of State Shinto. It subsequently apologized for its wartime actions.[6]

In contemporary times, Jōdo Shinshū is one of the most widely followed forms of Buddhism in Japan, although like other schools, it faces challenges from many popular Japanese new religions, or shinshūkyō, which emerged following World War II as well as from the growing secularization and materialism of Japanese society.

All ten schools of Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism commemorated the 750th memorial of their founder, Shinran, in 2011 in Kyoto.

Doctrine

Shinran's thought was strongly influenced by the doctrine of Mappō, a largely Mahayana eschatology which claims humanity's ability to listen to and practice the Buddhist teachings deteriorates over time and loses effectiveness in bringing individual practitioners closer to Buddhahood. This belief was particularly widespread in early medieval China and in Japan at the end of the Heian. Shinran, like his mentor Hōnen, saw the age he was living in as being a degenerate one where beings cannot hope to be able to extricate themselves from the cycle of birth and death through their own power, or jiriki (自力). For both Hōnen and Shinran, all conscious efforts towards achieving enlightenment and realizing the Bodhisattva ideal were contrived and rooted in selfish ignorance; for humans of this age are so deeply rooted in karmic evil as to be incapable of developing the truly altruistic compassion that is requisite to becoming a Bodhisattva.

Due to his awareness of human limitations, Shinran advocated reliance on tariki, or other power (他力)—the power of Amitābha (Japanese Amida) made manifest in his Primal Vow—in order to attain liberation. Shin Buddhism can therefore be understood as a "practiceless practice", for there are no specific acts to be performed such as there are in the "Path of Sages". In Shinran's own words, Shin Buddhism is considered the "Easy Path" because one is not compelled to perform many difficult, and often esoteric, practices in order to attain higher and higher mental states.

Nembutsu

As in other Pure Land Buddhist schools, Amitābha is a central focus of the Buddhist practice, and Jōdo Shinshū expresses this devotion through a chanting practice called nembutsu, or "Mindfulness of the Buddha [Amida]". The nembutsu is simply reciting the phrase Namu Amida Butsu ("I take refuge in Amitābha Buddha"). Jōdo Shinshū is not the first school of Buddhism to practice the nembutsu but it is interpreted in a new way according to Shinran. The nembutsu becomes understood as an act that expresses gratitude to Amitābha; furthermore, it is evoked in the practitioner through the power of Amida's unobstructed compassion. Therefore, in Shin Buddhism, the nembutsu is not considered a practice, nor does it generate karmic merit. It is simply an affirmation of one's gratitude. Indeed, given that the nembutsu is the Name, when one utters the Name, that is Amitābha calling to the devotee. This is the essence of the Name-that-calls.[7]

Note that this is in contrast to the related Jōdo-shū, which promoted a combination of repetition of the nembutsu and devotion to Amitābha as a means to birth in his pure land of Sukhavati. It also contrasts with other Buddhist schools in China and Japan, where nembutsu recitation was part of a more elaborate ritual.

The Pure Land

In another departure from more traditional Pure Land schools, Shinran advocated that birth in the Pure Land was settled in the midst of life. At the moment one entrusts oneself to Amitābha, one becomes "established in the stage of the truly settled". This is equivalent to the stage of non-retrogression along the bodhisattva path.

Many Pure Land Buddhist schools in the time of Shinran felt that birth in the Pure Land was a literal rebirth that occurred only upon death, and only after certain preliminary rituals. Elaborate rituals were used to guarantee rebirth in the Pure Land, including a common practice wherein the fingers were tied by strings to a painting or image of Amida Buddha. From the perspective of Jōdo Shinshū such rituals actually betray a lack of trust in Amida Buddha, relying on jiriki ("self-power"), rather than the tariki or "other-power" of Amida Buddha. Such rituals also favor those who could afford the time and energy to practice them or possess the necessary ritual objects—another obstacle for lower-class individuals. For Shinran Shonin, who closely followed the thought of the Chinese monk Tan-luan, the Pure Land is synonymous with nirvana.

Shinjin

The goal of the Shin path, or at least the practicer's present life, is the attainment of shinjin in the Other Power of Amida. Shinjin is sometimes translated as "faith", but this does not capture the nuances of the term and it is more often simply left untranslated.[8] The receipt of shinjin comes about through the renunciation of self-effort in attaining enlightenment through tariki. Shinjin arises from jinen (自然 naturalness, spontaneous working of the Vow) and cannot be achieved solely through conscious effort. One is letting go of conscious effort in a sense, and simply trusting Amida Buddha, and the nembutsu.

For Jōdo Shinshū practitioners, shinjin develops over time through "deep hearing" (monpo) of Amitābha's call of the nembutsu. According to Shinran, "to hear" means "that sentient beings, having heard how the Buddha's Vow arose—its origin and fulfillment—are altogether free of doubt."[9] Jinen also describes the way of naturalness whereby Amitābha's infinite light illumines and transforms the deeply rooted karmic evil of countless rebirths into good karma. It is of note that such evil karma is not destroyed but rather transformed: Shin stays within the Mahayana tradition's understanding of śūnyatā and understands that samsara and nirvana are not separate. Once the practitioner's mind is united with Amitābha and Buddha-nature gifted to the practitioner through shinjin, the practitioner attains the state of non-retrogression, whereupon after his death it is claimed he will achieve instantaneous and effortless enlightenment. He will then return to the world as a Bodhisattva, that he may work towards the salvation of all beings.

Tannishō

The Tannishō is a 13th-century book of recorded sayings attributed to Shinran, transcribed with commentary by Yuien-bo, a disciple of Shinran. The word Tannishō is a phrase which means "A record [of the words of Shinran] set down in lamentation over departures from his [Shinran's] teaching". While it is a short text, it is one of the most popular because practitioners see Shinran in a more informal setting.

For centuries, the text was almost unknown to the majority of Shin Buddhists. In the 15th century, Rennyo, Shinran's descendant, wrote of it, "This writing is an important one in our tradition. It should not be indiscriminately shown to anyone who lacks the past karmic good". Rennyo Shonin's personal copy of the Tannishō is the earliest extant copy. Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903) revitalized interest in the Tannishō, which indirectly helped to bring about the Ohigashi schism of 1962.[4]

In Japanese culture

Earlier schools of Buddhism that came to Japan, including Tendai and Shingon Buddhism, gained acceptance because of honji suijaku practices. For example, a kami could be seen as a manifestation of a bodhisattva. It is common even to this day to have Shinto shrines within the grounds of Buddhist temples.

By contrast, Shinran had distanced Jōdo Shinshū from Shinto because he believed that many Shinto practices contradicted the notion of reliance on Amitābha. However, Shinran taught that his followers should still continue to worship and express gratitude to kami, other buddhas, and bodhisattvas despite the fact that Amitābha should be the primary buddha that Pure Land believers focus on.[10] Furthermore, under the influence of Rennyo and other priests, Jōdo Shinshū later fully accepted honji suijaku beliefs and the concept of kami as manifestations of Amida Buddha and other buddhas and bodhisattvas.[11]

Jōdo Shinshū traditionally had an uneasy relationship with other Buddhist schools because it discouraged the majority of traditional Buddhist practices except for the nembutsu. Relations were particularly hostile between the Jōdo Shinshū and Nichiren Buddhism. On the other hand, newer Buddhist schools in Japan, such as Zen, tended to have a more positive relationship and occasionally shared practices, although this is still controversial. In popular lore, Rennyo, the 8th Head Priest of the Hongan-ji sect, was good friends with the famous Zen master Ikkyū.

Jōdo Shinshū drew much of its support from lower social classes in Japan who could not devote the time or education to other esoteric Buddhist practices or merit-making activities.

Outside Japan

During the 19th century, Japanese immigrants began arriving in Hawaii, the United States, Canada, Mexico and South America (especially in Brazil). Many immigrants to North America came from regions in which Jōdo Shinshū was predominant, and maintained their religious identity in their new country. The Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii, the Buddhist Churches of America and the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Temples of Canada (formerly Buddhist Churches of Canada) are several of the oldest Buddhist organizations outside of Asia. Jōdo Shinshū continues to remain relatively unknown outside the ethnic community because of the history of Japanese American and Japanese-Canadian internment during World War II, which caused many Shin temples to focus on rebuilding the Japanese-American Shin sangha rather than encourage outreach to non-Japanese. Today, many Shinshū temples outside Japan continue to have predominantly ethnic Japanese members, although interest in Buddhism and intermarriage contribute to a more diverse community. There are also active Jōdo Shinshū sanghas in the United Kingdom.[12]

During Taiwan's Japanese colonial era (1895–1945), Jōdo Shinshū built a temple complex in downtown Taipei.

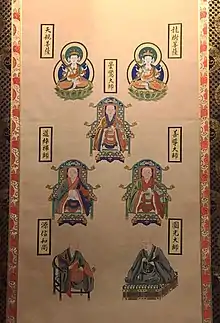

Shin patriarchs

The "Seven Patriarchs of Jōdo Shinshū" are seven Buddhist monks venerated in the development of Pure Land Buddhism as summarized in the Jōdo Shinshū hymn Shoshinge. Shinran quoted the writings and commentaries of the Patriarchs in his major work, the Kyogyoshinsho, to bolster his teachings.

The Seven Patriarchs, in chronological order, and their contributions are:[13][14][15][16]

| Name | Dates | Japanese Name | Country of Origin | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nagarjuna | 150–250 | Ryūju (龍樹) | India | First one to advocate the Pure Land as a valid Buddhist path. |

| Vasubandhu | ca. 4th century | Tenjin (天親) or Seshin (世親) | India | Expanded on Nagarjuna's Pure Land teachings, commentaries on Pure Land sutras. |

| Tan-luan | 476–542(?) | Donran (曇鸞) | China | Developed the six-syllable nembutsu chant commonly recited, emphasized the role of Amitabha Buddha's vow to rescue all beings. |

| Daochuo | 562–645 | Dōshaku (道綽) | China | Promoted the concept of "easy path" of the Pure Land in comparison to the tradition "path of the sages". Taught the efficacy of the Pure Land path in the latter age of the Dharma. |

| Shandao | 613–681 | Zendō (善導) | China | Stressed the importance of verbal recitation of Amitabha Buddha's name. |

| Genshin | 942–1017 | Genshin (源信) | Japan | Popularized Pure Land practices for the common people, with emphasis on salvation. |

| Hōnen | 1133–1212 | Hōnen (法然) | Japan | Developed a specific school of Buddhism devoted solely to rebirth in the Pure Land, further popularised recitation of name of Amitabha Buddha in order to attain rebirth in the Pure Land. |

In Jodo Shinshu temples, the seven masters are usually collectively enshrined on the far left.

Branch lineages

- Jōdo Shinshū Hongwanji School (Nishi Hongwan-ji)

- Jōdo Shinshū Higashi Honganji School (Higashi Hongan-ji)

- Shinshū Ōtani School

- Shinshū Chōsei School (Chōsei-ji)

- Shinshū Takada School (Senju-ji)

- Shinshū Kita Honganji School (Kitahongan-ji)

- Shinshū Bukkōji School (Bukkō-ji)

- Shinshū Kōshō School (Kōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Kibe School (Kinshoku-ji)

- Shinshū Izumoji School (Izumo-ji)

- Shinshū Jōkōji School (Jōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Jōshōji School (Jōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Sanmonto School (Senjō-ji)

- Montoshūichimi School (Kitami-ji)

- Kayakabe Teaching (Kayakabe-kyō) - An esoteric branch of Jōdo Shinshū

Major holidays

The following holidays are typically observed in Jōdo Shinshū temples:[17]

| Holiday | Japanese Name | Date |

|---|---|---|

| New Year's Day Service | Gantan'e | January 1 |

| Memorial Service for Shinran | Hōonkō | November 28, or January 9–16 |

| Spring Equinox | Higan | March 17–23 |

| Buddha's Birthday | Hanamatsuri | April 8 |

| Birthday of Shinran | Gotan'e | May 20–21 |

| Bon Festival | Urabon'e | around August 15, based on solar calendar |

| Autumnal Equinox | Higan | September 20–26 |

| Bodhi Day | Rohatsu | December 8 |

| New Year's Eve Service | Joyae | December 31 |

Major modern Shin figures

- Nanjo Bunyu (1848–1927)

- Saichi Asahara (1850-1932)

- Kasahara Kenju (1852–1883)

- Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903)

- Jokan Chikazumi (1870–1941)

- Eikichi Ikeyama (1873–1938)

- Soga Ryojin (1875–1971)

- Otani Kozui (1876–1948)

- Akegarasu Haya (1877–1954)

- Kaneko Daiei (1881–1976)

- Zuiken Saizo Inagaki (1885–1981)

- Takeko Kujo (1887–1928)

- William Montgomery McGovern (1897–1964)

- Rijin Yasuda (1900–1982)

- Gyomay Kubose (1905–2000)

- Shuichi Maida (1906–1967)

- Harold Stewart (1916–1995)

- Kenryu Takashi Tsuji (1919-2004)

- Alfred Bloom (1926–2017)

- Zuio Hisao Inagaki (1929–present)

- Shojun Bando (1932–2004)

- Taitetsu Unno (1935–2014)

- Eiken Kobai (1941–present)

- Dennis Hirota (1946–present)

- Kenneth K. Tanaka (1947-present)

- Marvin Harada (1953-present)

See also

References

- "The Essentials of Jodo Shinshu from the Nishi Honganji website". Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- Jeff Wilson, Mourning the Unborn Dead: A Buddhist Ritual Comes to America (Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 21, 34.

- "JODO SHU English". Jodo.org. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- Popular Buddhism In Japan: Shin Buddhist Religion & Culture by Esben Andreasen / University of Hawaii Press 1998, ISBN 0-8248-2028-2

- Moriarty, Elisabeth (1976). Nembutsu Odori, Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 35, No. 1 , pp. 7-16

- Zen at War (2nd ed.) by Brian Daizen Victoria / Rowman and Littlefield 2006, ISBN 0-7425-3926-1

- Griffin, David Ray (2005). Deep Religious Pluralism. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-664-22914-6.

- Hisao Inagaki (2008). ”Questions and Answers on Shinjin", Takatsuki, Japan. See Question 1: What is shinjin?

- Collected Works of Shinran, Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha, p. 112

- Lee, Kenneth Doo. (2007). The Prince and the Monk: Shotoku Worship in Shinran's Buddhism. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791470220.

- Dobbins, James C. (1989). Jodo Shinshu: Shin Buddhism in Medieval Japan. Bloomington, Illinois: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253331861. See especially pp. 142-143.

- "Front page". Three Wheels Shin Buddhist House. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

In 1994 Shogyoji established Three Wheels ('Sanrin shoja' in Japanese), in London, in response to the deep friendship between a group of English and Japanese people. Since then the Three Wheels community has grown considerably and serves as the hub of a lively multi-cultural Shin Buddhist Samgha.

- Watts, Jonathan; Tomatsu, Yoshiharu (2005). Traversing the Pure Land Path. Jodo Shu Press. ISBN 488363342X.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- "Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and teachers". Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

- "The Pure Land Lineage". Retrieved 2015-05-26.

- "Calendar of Observances, Nishi Hongwanji". Archived from the original on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

Literature

- Bandō, Shojun; Stewart, Harold; Rogers, Ann T. and Minor L.; trans. (1996) : Tannishō: Passages Deploring Deviations of Faith and Rennyo Shōnin Ofumi: The Letters of Rennyo, Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-03-6

- Bloom, Alfred (1989). Introduction to Jodo Shinshu, Pacific World Journal, New Series Number 5, 33-39

- Dessi, Ugo (2010), Social Behavior and Religious Consciousness among Shin Buddhist Practitioners, Japanese Journal of Religious Siudies, 37 (2), 335-366

- Dobbins, James C. (1989). Jodo Shinshu: Shin Buddhism in Medieval Japan. Bloomington, Illinois: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253331861; OCLC 470742039

- Ducor, Jerome (2021): Shinran and Pure Land Buddhism; San Francisco, Jodo Shinshu International Office; 188 pp., bibliography (ISBN 978-0-9997118-2-8).

- Inagaki Hisao, trans., Stewart, Harold (2003). The Three Pure Land Sutras, 2nd ed., Berkeley, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-18-4

- Lee, Kenneth Doo (2007). The Prince and the Monk: Shotoku Worship in Shinran's Buddhism. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791470220.

- Matsunaga, Daigan, Matsunaga, Alicia (1996), Foundation of Japanese Buddhism, Vol. 2: The Mass Movement (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods), Los Angeles; Tokyo: Buddhist Books International, 1996. ISBN 0-914910-28-0

- Takamori/Ito/Akehashi (2006). "You Were Born For A Reason: The Real Purpose of Life," Ichimannendo Publishing Inc; ISBN 9780-9790-471-07

- S. Yamabe and L. Adams Beck (trans.): Buddhist Psalms of Shinran Shonin, John Murray, London 1921. e-book

- Galen Amstutz, Review of Fumiaki, Iwata, Kindai Bukkyō to seinen: Chikazumi Jōkan to sono jidai and Ōmi Toshihiro, Kindai Bukkyō no naka no Shinshū: Chikazumi Jōkan to kyūdōshatachi, in H-Japan, H-Net Reviews July, 2017.

External links

- List of Jodo Shinshu Organisations with Links

- Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, Dharma for the Modern Age A basic portal with links.

- Homepage for Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha Hongwanji International Center - English

- Buddhist Churches of America Includes basic information, shopping for Shin Buddhist ritual implements, and links to various Shin churches in America.

- Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Temples of Canada National website, includes links and addresses of Shin temples throughout Canada.

- Institute of Buddhist Studies: Seminary and Graduate School

- Jodo Shinshu Honganji-ha. Shinran Works The collected works of Shinran, including the Kyōgōshinshō.

- nembutsu.info: Journal of Shin Buddhism

- The Way of Jodo Shinshu: Reflections on the Hymns of Shinran Shonin