Johann Schönberg

Johann Nepomuk Schönberg (1844 – 2 December 1913) was an Austrian artist, war correspondent, war-artist, and illustrator who illustrated many of the wars and disasters of his time.

Johann Nepomuk Schönberg | |

|---|---|

Johann Schönberg in 1892 | |

| Born | 1844 Vienna |

| Died | (aged 69) |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Other names | J Schonberg |

| Occupation(s) | Artist, Illustrator |

| Years active | 1862–1905 |

| Known for | Illustrations of war |

| Notable work | Paintings of the Romanian War of Independence |

Early life

Both his father Adolf (1813–1868) an engraver and lithographer, and his grandfather Johan (1780 – 12 March 1863) an engraver, were well known artists.[1] Schönberg attended the Imperial and Royal Unified Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna from 1858 to 1860, where his father had also studied.[2] He travelled to Munich to work under Hermann Anschütz at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich. However, he had to abandon his studies to Vienna to assist his impoverished father. Fritz L'Allemand had seen some of his smaller war paintings and asked him to assist with completing his painting of "Banquet Table of the Maria Theresa Knights at Schönbrunn Castle". Schönberg spent several months at this task, it was the L'allemand who got paid and got the credit.[1]

Schönberg was of military age and served as a soldier in the Austrian army and fought in the Battle of Custoza (1866) as part of the Third Italian War of Independence. He also served in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, and supplied sketches from this conflict to the Illustrated London News. Before and after his bouts of military service, he was studying in Vienna and Munich.[3] He was already producing illustrations for books and for illustrated papers. During this period also he visited the Academy in Vienna in (1865–1867) and became a member of the Vienna Artists' Society at the Vienna Künstlerhaus.[2]

He married Pauline (born c. 1850) in c. 1873. The couple had no children. They both moved to England about the time of their marriage.[4] In 1901, when Schönberg was in China, the census shows Pauline was staying with a cousin in Ernst Carl Fuchs at Penge in Kent. By the 1911 census, the couple, now in their 60s were boarding with the Bruck brothers, Walter, a fine art publisher, and William, a process engraver, in Weylands, 21, Southend Road, Beckham. The couple never naturalised, but continued to remain resident foreign citizens.

Work

During his life, Schönberg produced a huge volume of work. His overall body of work numbers more than 2,000 drawings and paintings.[2] His paintings were usually commissioned rather than being painted as speculative works. He almost never exhibited,[note 1] and did not build up a reputation in this way. Wurzbach noted that Schönberg's sketches were well drawn, gave a faithful rendering of the scenes, and when many people were represented, the groups were cleverly distributed and the timing of the drawing chosen with a lucid eye. However, Wurzbach bemoaned that Schönberg's talent was being frittered away on illustration rather than on great works of art.[1]

One interesting commission that Schönberg received was from Prince Carol of the newly independent Romania. The Prince commissioned him to paint the key events of the Romanian War of Independence. Specifically, he was commissioned to paint a series of six oil paintings:

- The Crossing of the Danube[note 2]

- The Bombardment of Vidin, also called This is the music I like! after the Prince's words when a shell burst near him on a battery in Calafat

- The Assault on the Grivitza Redoubt

- The Ruling Prince visiting the Grivitza Redoubt

- Prince Carol at the Battle of Plevna

- The first Encounter between Prince Carol I and Osman Nuri Pasha after the Surrender

The paintings were based on Schönberg's own witnessing of these events, and were based on his own sketches and drawings made during the campaign. He worked hard to ensure that all those represented were accurately drawn. It was a long drawn out process as he first had to produce watercolour sketches and mid-sized oil paintings to get approval for the large-scale oil-paintings.[note 3][3] The whole project took 25 years to complete.[7]

Bénézit shows only one auction result for Schönberg: Sailing Ships at Sea (1912, oil on canvas 53.5x37 cm) was sold for 15,000 ATS[note 4] in Vienna on 19 June 1979.[8]

Press illustrations

Schönberg provided illustrations for many publications, starting in his native Austria and then moving further afield to Germany, France, and England. Among the papers he illustrated for were:

- Über Land und Meer (Stuttgart)[1] This was a Hallberger publication like Illustrirte Welt, but they did not publish the same material.[9]

- Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig)[2]

- Daheim[2]

- Illustrierte Welt[2]

- Le Monde Illustré[2]

- Illustrated London News Schönberg first works for the paper in 1866.[10] He was appointed as their Special Artist in Romania in 1877 during the Romanian War of Independence. He remained on the staff of the newspaper for the next 22 years, until he went to Pretoria for The Sphere in 1899.[11]: 620 He returned to the Illustrated London News after returning from Pretoria.[12]

- The Sphere[12]

Schönberg not only did his own drawings, but he also worked up the drawings sent in by other artists. For the illustrated weeklies, the illustrations were a two-stage process – the first with the production of the drawing, and then the engraving of the plates to reproduce them. Thus Schönberg worked on Melton Prior's drawings of the Zulu War in 1879.[13] Houfe states that his illustration style was characterised by the heavy use of body-colour with grey washes.[14]

Examples of illustrations from war zones

The following illustrations were drawn or painted by Schönberg during different military campaigns. They all show examples of military medicine as the illustrations are by courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

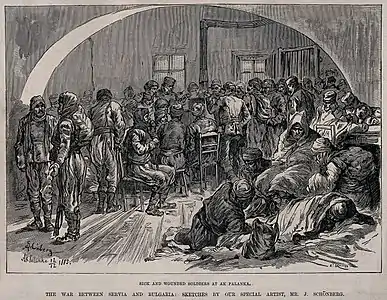

Sick and wounded soldiers at Ak Palanka during the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885

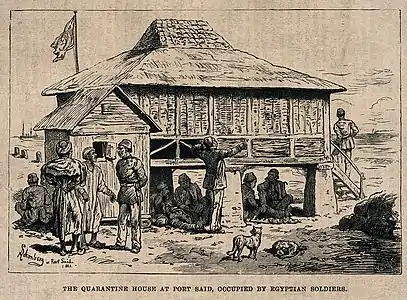

Sick and wounded soldiers at Ak Palanka during the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885 The Quarantine House for Egyptian soldiers suffering from the plague at Port Said during the British Conquest of Egypt (1882)

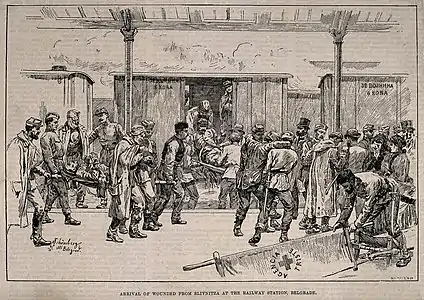

The Quarantine House for Egyptian soldiers suffering from the plague at Port Said during the British Conquest of Egypt (1882) Arrival of wounded from Slivnitza at Belgrade Railway station during the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885

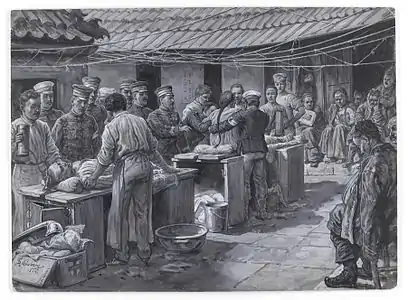

Arrival of wounded from Slivnitza at Belgrade Railway station during the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885 Wounded Chinese prisoners getting medical treatment at Pyongyang, Korea, during the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

Wounded Chinese prisoners getting medical treatment at Pyongyang, Korea, during the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

Schönberg was a correspondent as well as an artist and sent reports and conducted interviews, in addition to sending sketches of the action or of the aftermath of war. Among the conflicts and disasters he covered were:

- The American Civil War (12 April 1861 – 9 May 1865). Schönberg told a Canadian reporter in a 1901 interview, while he was on his way back from the Boxer Rebellion via Vancouver,[note 5][note 6] that his first experience in the field was in 1863 when he drew military illustrations of the Civil War.[3]

- The Third Italian War of Independence (20 June 1866 – 12 August 1866). Schönberg was a soldier in the Austrian ranks for this war, but also did some illustration.[3]

- The Austro-Prussian War (14 June – 22 July 1866). This was the first work he did for the Illustrated London News.[12] He was also in the ranks of the Austrian Army for this conflict.[3]

- The Franco-Prussian War (19 July 1870 – 28 January 1871). He later contributed to a book on the campaign.[2]

- The Prusso-Austrian War (14 June – 22 July 1855) where he produced drawings for the Illustrated London News, his first work for that paper.[12]

- The Serbo-Turkish War (30 June 1876 – 28 February 1877). This was the first of two wars that established Serbia as an independent state. In the lull between the two wars, Schönberg covered the tension in Bulgaria as the Special Artist for the Illustrated London News.[4]

- Russo-Turkish War otherwise known as the Romanian War of Independence (24 April 1877 – 3 March 1878). Schönberg covered this war in the interlude between the two Serbian wars as the Special Artist for the Illustrated London News.[15] As a result of his work on this war, Prince Carol I of Romania asked him to paint six large canvases inspired by the war with the topics selected by the Prince. The first painting was ready in 1891 and it was 1903 before the sixth was handed over.

- The Russo-Turkish War (13 December 1877 – 5 February 1878). This was effectively a continuation of the (1876–1877) conflict.[4]

- The flooding of Szegedin, Hungary in 1879, a disaster which destroyed over 90% of the houses.[16]

- The British Conquest of Egypt (1882) Egyptian campaign of July–September 1882.[4]

- The Serbo-Bulgarian War (14–28 November 1885)

- The cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892 when over 8,000 died.[17]

- The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895)

- The Second Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902). [note 7]

- The Boxer Rebellion or Yihetuan Movement (2 November 1899 – 7 September 1901).[note 8]

Book illustrations

In addition to his illustrations for non-fiction works such as Alexander Patuzzi's History of the Popes, and Ludwig von Alvensleben's General History of the World, Schönberg illustrated books for a wide range of authors, mainly for children's fiction. Among the authors whose work he illustrated were:

- Elbridge S. Brooks, a prolific author who wrote both serialised fiction, novels, and non-fiction for children

- Harry Collingwood, a writer of boys' adventure fiction, usually in a nautical setting

- Edward S. Ellis, a prolific American author of adventure fiction

- George Manville Fenn, who wrote mainly for young adults

- Henry Frith, a prolific Irish author and the English translator for many of Jules Verne's novels

- John Percy Groves, a soldier who wrote stirring stories for boys

- G. A. Henty, a prolific writer of boy's adventure fiction, often set in a historical context

- Georgina Norway, who wrote adventure fiction for children as "G. Norway"

Examples of book illustration

Given his Austrian roots, Schönberg was probably a good choice for the illustration of The Lion of the North: a tale of the times of Gustavus Adolphus and the wars of religion by G. A. Henty. Schönberg did twelve full-page illustrations as line-and-wash drawings reproduced by black line and sepia tint plates.[11]: 130 Newbolt notes that Schönberg's work was limited by the quality of available processes and sometimes by the printer's choice of cheap paper.[11]: 620

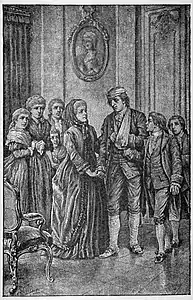

Colonel Munro seeks to enlist Nigel Graeme and his nephew

Colonel Munro seeks to enlist Nigel Graeme and his nephew Malcolm's courage and humanity at the battle of Schiefelbrune

Malcolm's courage and humanity at the battle of Schiefelbrune Colonel Munro presents Malcolm to the King

Colonel Munro presents Malcolm to the King Malcolm counsels the townspeople of Mansfield to resistance

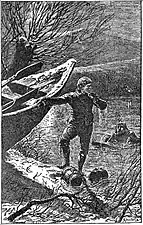

Malcolm counsels the townspeople of Mansfield to resistance Malcolm and Grent cross the Rhine at midnight

Malcolm and Grent cross the Rhine at midnight Malcolm fired at one of the natives and then with a loud shout dashed forward

Malcolm fired at one of the natives and then with a loud shout dashed forward The last of the siege of the church-tower

The last of the siege of the church-tower Death of Gustavus Adolphus at Lutzen

Death of Gustavus Adolphus at Lutzen Malcolm receives Lady Hilda's appeal for help

Malcolm receives Lady Hilda's appeal for help A plan proposed for Thekla's safety

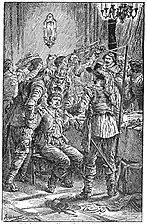

A plan proposed for Thekla's safety Malcolm overpowered by treachery at the banquet

Malcolm overpowered by treachery at the banquet Thekla advanced and laid her hand in Malcolm's

Thekla advanced and laid her hand in Malcolm's

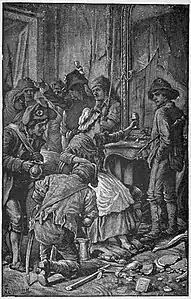

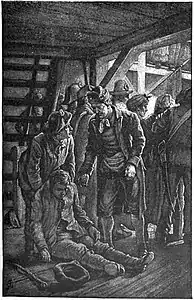

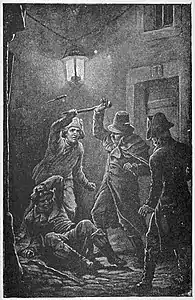

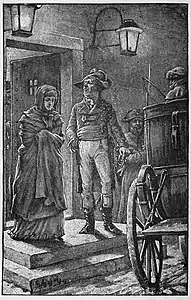

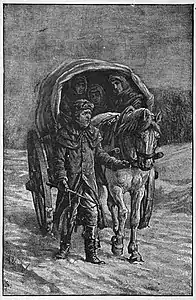

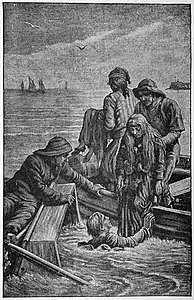

Schönberg illustrated another Henty tale of trouble on the continent. This time it was In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy, (1888), London, Blackie, a story about the French Revolution. Schönberg did eight full-page wash-drawings which were reproduced by halftone blocks printed in black on coated paper. The halftone blocks were fine-screen, almost the first time such blocks were used in the UK. A lot of handwork and deep-etching was done on the blocks to accentuate highlight and avoid a flat result. [11]: 163 Newbolt further notes that examination with a glass shows that Blackie had printing problems with these very fine screens, which tended to get clogged by dust and ink, as Blackie had begun with screens which were too fine for the quality of paper they were using.[11]: 618

Harry saves the girls from the mad dog

Harry saves the girls from the mad dog The Marquis returns to his family

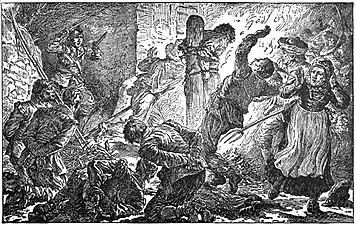

The Marquis returns to his family The wreck of the Marquis's mansion

The wreck of the Marquis's mansion Victor de Gisons struck down by a friendly blow

Victor de Gisons struck down by a friendly blow Robespierre saved from the assassins

Robespierre saved from the assassins Citizen Lebat takes Marie out of prison

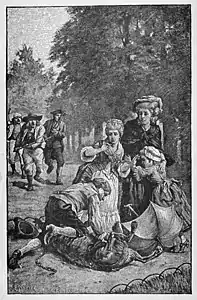

Citizen Lebat takes Marie out of prison The journey to Nantes

The journey to Nantes Jeanne and Virginie are rescued from the massacre

Jeanne and Virginie are rescued from the massacre

Death

Schönberg died on 2 December 1913 in Beckenham, London. He was still living at Weylands, 21 Southend Road Beckham when he died. He was buried in Lambeth North Cemetery on 6 December.[23] His widow Pauline administered his estate, which amounted to only £48 10s.[24]

Notes

- One exception appears to have been the Royal Academy in 1895 where he exhibited two works including Japanese Soldiers in a Snow-Storm.[5] These are the only exhibits by Schönberg listed in A Dictionary of British Artists.[6]

- The crossing of the Danube was such a pivotal point that Prince Carol introduced a decoration for heroism in the War of Independence called the Crossing of the Danube Cross.

- A photograph of Schönberg in his studio working on one of the canvasses shows a canvas of about approximately 2.5 m wide by 1.5 m high (8 foot by 5 foot). He is using two other easels, one with his reference painting of Prince Carol, and the other presumably the approved watercolour showing the composition of the large oil painting.

- The Austrian Schilling (ATS) was replaced by the Euro on 1 January 1999, on which date, 15,000 ATS was worth 1,090 EUR.

- This route meant sailing the pacific to Vancouver, then travelling by train to the East Coast to take another ship across the Atlantic. He planned a brief visit to Niagara on his way to New York to catch his ship for Europe. He was keen to return to London so that he could finally finish the commission that Carol I had given him 23 years earlier. He would finally finish it in 1903.

- The journalist referred to him arriving in Vancouver on the Empress. This was presumably the RMS Empress of China (1890), but it could have been one of the other two Canadian Pacific Steamships Empresses linking Vancouver and Asia, the RMS Empress of Japan (1890) and the RMS Empress of India (1890).

- As war was looming in 1899, the editor of the yet unborn The Sphere in November decided that the new paper could gain a scoop by having an artist in the heart of the enemy.[18]: 25-26 He asked Schönberg to travel to Pretoria, South Africa as their clandestine correspondent, nominally working for a German newspaper. He wanted him to cover the conflict from the Boer side. On arrival in Durban, he sought permission to travel on to Lourenço Marques, now Maputo, from where a railway served Pretoria. The British officer in charge of onward transport did not believe his story and thinking that he was a German officer come to help the Boers, gave him 24 hours to leave the Colony. He did so, but in a French steamer that dropped him in Maputo.[19] He interviewed Joubert and made many sketches of the campaign, one even showing the prison camp for captured British officers.[20] While he was in Pretoria, The Sphere published his drawings, but with this signature erased.[18]: 26 His time with the Boers came to an end when The Sphere blew his cover by sending him a telegram saying say that London would like him to remain.[19] However, it is surprising that Pretoria did not smell a rat earlier as his Austrian Passport gives London as his residence, and signed his name a d John rather than Johann.[18]: 26 He was slightly wounded by a shell during the campaign.[21]

- Schönberg was one of only ten war correspondents awarded the China War Medal after this campaign.[12] However, he arrived in Beijing long after the fighting had finished.[22]Schönberg was originally accredited to the Japanese Army, but on arrival in China he fell in with a Major Scott in charge of Indian Troops, with Baluchi, Sikh, and Parthan contingents. He abandoned his accreditation to the Japanese and stayed with Major Scott. Schönberg was disgusted with the wanton killings by Allied troops, with the Russian being the worst, ably assisted by the Germans and the French. He also reproved the acts of pillage by the Allied troops, with the destruction of the Pekin conservatory, founded by the Jesuits three centuries earlier, being one of the worst examples.[3]

References

- Constantin von Wurzbach (1876). Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich0: enthaltend die Lebensskizzen der denkwürdigen Personen, welche 1750 bis 1850 im Kaiserstaate und in seinen Kronländern gelebt haben. Schnabel - Schröter. 31. Zamarski. pp. 123–125. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Wacha, G. "Schönberg, Johann Nep. (1844-1913), Maler und Illustrator". Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "In the path of two wars: Incidents of the Battlefield Related by the Famous War Artist Herr Schonberg". The Province, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (Saturday 4 May 1901): 15. 4 May 1901.

- "In the Path of Two Wars". The Province. 4 May 1901. p. 15. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Wood, Christopher (1978). "Schonberg, John". Dictionary of Victorian Painters (2nd. ed.). p. 418.

- Johnson, J.; Greutzner, A. (8 June 1905). The Dictionary of British Artists 1880-1940. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 449.

- Ionescu, Adrian-Silvan (1999). "Picturi Puţin Cunoscute Cu Subiecte Din Războiul De Independenţă Datorate Lui Johann Nepomuk Schônberg (Little Known Paintings With Subjects From The War of Independence by Johann Nepomuk Schönberg)". Muzeul Naţional (National Museum). XI: 85–105.

- Bénézit, Emmanuel (2006). Benezit Dictionary Of Artists. Vol. 12: Rouco-Sommer. Paris: Editions Gründ. p. 740. ISBN 978-2-7000-3082-2. Retrieved 11 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- Thomas Smits (5 December 2019). The European Illustrated Press and the Emergence of a Transnational Visual Culture of the News, 1842-1870. Taylor & Francis. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-00-076722-3. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- Hodgson, Pat (1977). "Johann Nepomuk Schönberg (1844-?)". The War Illustrators. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. p. 131.

- Newbolt, Peter (1996). G.A. Henty, 1832-1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Lot 60: Date of Auction: 19th September 2003: Awards to Civilians from the Collection of John Tamplin: The Boxer campaign medal awarded to Mr John Schonberg, the noted War Correspondent and Artist of many conflicts: Footnote". Dix Noonan Webb. 2003. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Houfe, Simon (1981). Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914 (Rev. ed.). Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 143. Retrieved 14 July 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- Houfe, Simon (1996). Dictionary of 19th Century British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 293. ISBN 1-85149-193-7.

- "H.M.S. Rapid at Kustendje". Illustrated London News (Saturday 1 September 1877): 13. 1 September 1877.

- "Innundation at Szegedin". Illustrated London News (Saturday 5 April 1879): 17. 5 April 1879.

- "The Cholera". British Medical Journal. 1 (1677): 373–375. 18 February 1893. JSTOR 20223584.

- Greenwall, Ryno (14 June 1905). Artists and Illustrators of the Anglo-Boer War. Vlaeberg, Western Cape, South Africa: Fernwood Press. ISBN 0-9583154-2-6.

- "The Return of Our Special Artist from Pretoria: Some Account of the Adventures of John Schonberg". The Sphere (Saturday 16 June 1900): 14. 16 June 1900.

- "How the captive British Officers were guarded at night-time in Pretoria". The Sphere (Saturday 16 June 1900): 18. 16 June 1900.

- ""The Sphere" Special Correspondents in the Transvaal and China". The Sphere (Saturday 4 August 1900): 21. 4 August 1900.

- Mitchel P. Roth; James Stuart Olson (1997). Historical Dictionary of War Journalism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-313-29171-5.

- London Metropopolitan Archives. "Reference Number: DW/T/0964". Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906 and Church of England Parish Registers, 1813-2003. London Metropolitan Archives, London. London: London Metropolitan Archives.

- "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Schonberg and Year of Death 1914". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

External links

- Paintings by Schonberg in public collections in the UK (ArtUK).

- Works by Johann Schönberg at Project Gutenberg

- Books illustrated by Schönberg at the Hathi Trust.

- illustrations by Schönberg at the Wellcome Collection