Jean-Louis Le Loutre

Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre (French: [ʒɑ̃lwi ləlutʁ]; 26 September 1709 – 30 September 1772) was a Catholic priest and missionary for the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Le Loutre became the leader of the French forces and the Acadian and Mi'kmaq militias during King George's War and Father Le Loutre's War in the eighteenth-century struggle for power between the French, Acadians, and Miꞌkmaq against the British over Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick).

Jean-Louis Le Loutre | |

|---|---|

Vicar general Le Loutre | |

| Born | September 26, 1709 Morlaix, France |

| Died | September 30, 1772 (age 63) Nantes, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | French missionary |

| Rank | Vicar General of Acadia |

| Battles/wars | King George's War |

| Signature | |

Historical context

_-_Geographicus_-_AmeriqueSeptentrionale-covensmortier-1708.jpg.webp)

Nova Scotia had been under the rule of the British since the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. The British were settled mostly in the capital Annapolis Royal, while Acadians and the native Mi'kmaq occupied the rest of the region. Île-Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island) remained under French control, as it had been granted to the French under the Treaty of Utrecht, and the mainland portion of Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) was British and contested by the French.

In 1738, the French had no formal military presence at mainland Nova Scotia because they had been evicted in 1713. The Acadians had refused to sign a loyalty oath to the British Crown since the defeat in Port-Royal in 1710, but the settlers were unable to assist French efforts to recapture Nova Scotia without French military support.

Life

Le Loutre was born in 1709 to Jean-Maurice Le Loutre Després, a paper maker, and Catherine Huet, the daughter of a paper maker, in the parish of Saint-Matthieu in Morlaix, France in Brittany. In 1730, the young Le Loutre entered the Séminaire du Saint-Esprit in Paris; both his parents had already died. After completing his training, Le Loutre transferred to the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères (Seminary of Foreign Missions) in March 1737, as he intended to serve the church abroad. Most of the priests associated with the Paris Foreign Missions Society were assigned as missionaries to Asia, particularly during the nineteenth century, but Le Loutre was assigned to eastern Canada and the Mi'kmaq, an Algonquian-speaking people. Le Loutre arrived at mainland Nova Scotia in 1738.

Île Royale

Shortly after being ordained, Le Loutre sailed for Acadia and arrived in Louisbourg, Île-Royale, New France in the autumn of 1737. He spent about a year at Malagawatch, Île-Royale, working with missionary Pierre Maillard to learn the Miꞌkmaq language. Le Loutre was assigned to replace Abbé de Saint-Vincent, at the Mission Sainte-Anne in Shubenacadie. He left for Saint-Anne's on 22 September 1738. His duties included the French posts at Cobequid and Tatamagouche. Lawrence Armstrong was lieutenant-governor at Annapolis Royal. Although Armstrong was initially annoyed that La Loutre hadn't presented himself at Annapolis Royale, on the whole, La Loutre's relations with the British authorities remained cordial.[1]

King George's War

The conquest of Acadia by Great Britain began with the 1710 capture of the provincial capital, Port Royal. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France formally ceded Acadia to Britain. However, there was disagreement about the provincial boundaries, and some Acadians also resisted British rule. With renewed war imminent in 1744, the leaders of New France formulated plans to retake what the British called Nova Scotia with an assault on the capital, which the British had renamed Annapolis Royal.

Siege of Annapolis Royal

During King George's War, the neutrality of Le Loutre and the Acadians was tested. By the end of the war, most British officials who had been sympathetic toward the Acadians concluded that they and Le Loutre were supportive of the French position. Le Loutre may have been involved in two raids on the British at Annapolis Royal. The first Siege of Fort Anne was made in July 1744 but ended after four days due to the failure of French naval support to arrive.[1]

A second attempt in September was orchestrated by François Dupont Duvivier. Without with siege guns and cannon, Duvivier could make little headway. In the late-spring/early summer Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor Paul Mascarene wrote to Massachusetts governor William Shirley requesting military aid. Gorham's Rangers arrived in late September to reinforce the garrison. Wampanoag, Nauset, and Pequawket members were offered bounties for Mi'kmaq scalps and prisoners as part of their pay. The Mi'kmaq's withdrew and Duvivier was forced to retreat back to Grand Pré in early October. After the two attacks on Annapolis Royal, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley put a bounty on the Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet.[2]

The following year, Louisburg fell for the first time to a force of New Englanders. After the capture of Louisberg, the British attempted to lure La Loutre to come there for his own safety, but he chose to go to Québec to confer with the authorities. They made Le Loutre their liaison with the Mi'kmaq, who were already at war with the British along the frontier. Thus the French government could work with the Mi'kmaq militia in Acadia.

Duc d'Anville Expedition

Yet another attempt at Annapolis Royal was organized with Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay and the ill-fated Duc d'Anville Expedition in 1746. With Louisbourg captured by the British, Le Loutre became the liaison between the Acadian settlers and French expeditions by land and sea. The authorities directed him to receive the expedition at Baie de Chibouctou (Halifax Harbour in present-day Halifax, Nova Scotia). Le Loutre was virtually the only person to know the signals to identify the ships of the fleet. He had to coordinate the operations of the naval force with those of the army of Ramezay, sent to retake Acadia by capturing Annapolis Royal early in June 1746. Ramezay and his detachment arrived at Beaubassin (near present-day Amherst, Nova Scotia) in July, when only two frigates of the French squadron had reached Baie de Chibouctou. Without seeking the agreement of the two captains, Le Loutre wrote to Ramezay suggesting an attack be made on Annapolis Royal without the full expedition; but his advice was not acted upon. They waited over two months for the expedition to arrive; slowed by contrary winds and ravaged by disease, the expedition returned home.

After the failed expedition, Le Loutre returned to France. While in France, he made two attempts during the war to return to Acadia. On both occasions he was imprisoned by the English. In 1749, after the war, he finally returned.

Father Le Loutre's War

Le Loutre moved his base of operation in 1749 from Shubenacadie to Pointe-à-Beauséjour on the Isthmus of Chignecto. When Le Loutre arrived at Beauséjour, France and England were disputing the ownership of present-day New Brunswick. A year after they established Halifax in 1749, the British built forts in the major Acadian communities: Fort Edward (at Piziquid), Fort Vieux Logis at Grand Pré and Fort Lawrence (at Beaubassin). They were also interested in building forts in the various Acadian communities to control the local populations.

Le Loutre wrote to the minister of the Marine, "As we cannot openly oppose the English ventures, I think that we cannot do better than to incite the Mi'kmaq to continue warring on the English; my plan is to persuade the Mi'kmaq to send word to the English that they will not permit new settlements to be made in Acadia. … I shall do my best to make it look to the English as if this plan comes from the Mi'kmaq and that I have no part in it."[3]

Governor General Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel de la Jonquière, Marquis de la Jonquière, wrote in 1749 to his superior in France, "It will be the missionaries who will manage all the negotiation, and direct the movement of the savages, who are in excellent hands, as the Reverend Father Germain and Monsieur l'Abbe Le Loutre are very capable of making the most of them, and using them to the greatest advantage for our interests. They will manage their intrigue in such a way as not to appear in it."[4]

As an official peace existed between France and Britain, Le Loutre led the guerrilla resistance to the British building forts in the Acadian villages, because the French army was unable to fight the British, who possessed the territory. Le Loutre and the French were established at Beauséjour, just opposite Beaubassin. Charles Lawrence first tried to establish control over Beauséjour and then at Beaubassin early in 1750, but his forces were repelled by Le Loutre, the Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in setting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.[5]

Defeated at Beaubassin, Lawrence went to Piziquid where he built Fort Edward; he forced the Acadians to destroy their church and replaced it with the British fort.[6] Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin to build Fort Lawrence. He encountered continued resistance there, with the Mi'kmaq and Acadians dug in before Lawrence's return to defend the remains of the village. Le Loutre was joined by the Acadian militia leader Joseph Broussard. They were eventually overwhelmed by force, and the New Englanders erected Fort Lawrence at Beaubassin.

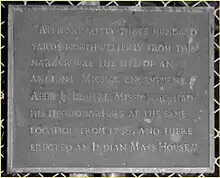

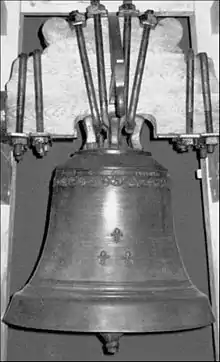

In the spring of 1751, the French countered by building Fort Beauséjour. Le Loutre saved the bell from Notre Dame d'Assumption Church in Beaubassin and put it in the cathedral he had built beside Fort Beauséjour. In 1752 he proposed a plan to the French court to destroy Fort Lawrence and return Beaubassin to the Mi'kmaq and Acadians.

Both New England and New France military officials made allies of the aboriginal tribes in their struggles for control. The aboriginal allies also engaged independently in warfare against the colonists and opposing tribes, without their English or French allies. Often aboriginal allies fought on their own while the imperial powers tried to conceal their involvement in such initiatives, to prevent igniting large-scale warfare between England and France. Le Loutre worked with the Mi'kmaq to harass British settlers and prevent the expansion of British settlements. By the time Cornwallis had arrived in Halifax, there was a long history of conflict between the Wabanaki Confederacy (which included the Mi'kmaq) and the British.

Governor Edward Cornwallis was informed in August that two vessels were attacked by the Indians at Canso whereby "three English and seven Indians were killed." Council believed the attack had been orchestrated by an Abbe Le Loutre.[7] The Governor offered a reward of £50 for capture of La Loutre dead or alive.

Raid on Dartmouth (1749)

On September 30, 1749 when a Mi'kmaq force from Chignecto raided Major Ezekiel Gilman's sawmill at present-day Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, killing four workers and wounding two. In response, Cornwallis issued a proclamation offering a bounty for the capture or scalps of Mi'kmaw men and for the capture of women and children: "every Indian you shall destroy (upon producing his Scalp as the Custom is) or every Indian taken, Man, Woman or Child."[8]

In this Cornwallis followed the example set in New England. He set the price at the same rate that the Mi'kmaq received from the French for British scalps.[9][10] Rangers scoured the area around Halifax looking for Mi'kmaq, but never found any.[9]

Acadian exodus (1750–52)

With the founding of Halifax and the British occupation of Nova Scotia intensifying, Le Loutre led the Acadians who lived in the Cobequid region of mainland Nova Scotia to New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Cornwallis tried to prevent the Acadians from leaving as the English preferred to retain their substantial economic value in farming. However, deputies of the Acadian communities presented him with a petition to allow them to refuse to take arms against fellow Frenchman or they would leave. Cornwallis strongly refused their request and directed them that if they left, they could not take any belongings, and warned them that if they went to the area north of the Missaguash River they would still be in English territory and still be British subjects.

The Cobequid Acadians wrote to the people in Beaubassin about British soldiers who, "... came furtively during the night to take our pastor [Girard] and our four deputies .... [A British officer] read the orders by which he was authorized to seize all the muskets in our houses, thereby reducing us to the condition of the Irish.... Thus we see ourselves on the brink of destruction, liable to be captured and transported to the English islands and to lose our religion."[11]

Despite Cornwallis' threats, most Acadians in the Cobequid followed Le Loutre. The priest tried to establish new communities, but found it difficult to supply the new settlers, the Mi'qmaq, and the garrisons at Fort Beauséjour and Île Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) with food and other necessities. Finding the living conditions deplorable at New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, he made repeated appeals in 1752 for aid from the authorities in Quebec. He returned to France to seek funds, which he gained in 1753 from the courts, for the purpose of building dykes in Acadia. Protecting low-lying lands from the tides would enable their use as pasture for cattle and development with cultivation for crops, so the Acadians could escape the risk of starvation. Granted additional monies, Le Loutre sailed back to Acadia with other missionaries in 1753.

Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755)

In 1754 Bishop Henri-Marie Dubreil de Pontbriand of Quebec appointed Le Loutre vicar-general of Acadia. He continued to encourage the Mi'kmaq to harass the British. He directed Acadians from Minas and Port Royal to assist in building a cathedral at Beauséjour. It was an exact replica of the original Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral.[12] A month after the cathedral was completed, the British attacked. Upon the imminent fall of Fort Beauséjour, Le Loutre burned the cathedral to the ground to prevent its falling into the hands of the British. He had the bell removed and saved. Not only were such cast bells expensive, that particular bell was a symbolic act of hope for rebuilding, as he had brought it from the church at Beaubassin when that village was burned. The defeat was the catalyst for the Deportation of the Acadians. The bell is held at the Fort Beauséjour National Historic Site.

Imprisonment, death and legacy

Aware of his risk, Le Loutre escaped to Quebec through the woods. In the late summer, he returned to Louisbourg and sailed for France. His ship was seized by the British in September 1755, and Le Loutre was taken prisoner. After three months in Plymouth,[13] he was held in Elizabeth Castle, Jersey, for eight years, until after the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) that ended the Seven Years' War.

After that, he tried to help Acadians deported to France to settle in areas such as Morlaix, Saint-Malo, and Poitou. Le Loutre died at Nantes on 30 September 1772 on a trip to Poitou to show Acadians the land. He was buried the following day at the Church of St. Leonard. Le Loutre willed his worldly possessions to the displaced Acadians.

Historian Micheline Johnson has described him as "the soul of the Acadian resistance,"[14] and he enjoyed wide support amongst French-Canadian priest-historians of the 19th and 20th centuries. A street of Gatineau, Quebec, is named in his memory.

References

- Finn, Gérard (1979). "Le Loutre, Jean-Louis". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Williamson, William D. (1832). The History of the State of Maine: From Its First Discovery, 1602, to the Separation, A. D. 1820, Inclusive. Vol. II. Hallowell, Maine: Glazier, Masters & Company. p. 218.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5.

- Parkman, p. 50

- Gentleman's Magazine Vol 20 July 1750 p. 295

- Bujold, Stéphan (2004). "L'Acadie vers 1750. Essai de chronologie des paroisses acadiennes du bassin des Mines (Minas Basin, NS) avant le Grand dérangement". Études d'histoire religieuse. 70: 57–77. doi:10.7202/1006673ar.

- Akins, Thomas (1895). History of Halifax City. Halifax: Nova Scotia Historical Society. p. 18. ISBN 9780888120014.

- Dickason, Olive (1971). Louisbourg and the Indians: A Study in Imperial Race Relations, 1713-1760 (PDF) (MA). University of Ottawa. p. 138. doi:10.20381/ruor-9436. referencing Cornwallis' instructions to Capt. Silvanus Cobb, commanding the sloop York, 13 January 1750

- Akins (1895), p. 19.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3. p. 152. The decision of Cornwallis and the fellow members of the Nova Scotia Council to issue a scalp bounty was influenced by the precedents set by other colonial administrations in British North America, and two companies of rangers from New England were formed to scour the area around Halifax, though they never found any Mi'kmaq. The decision to issue a scalp bounty remains controversial, and British military officers (including Cornwallis, Winslow and Jeffery Amherst expressed dismay over the tactics employed by both the rangers and the Mi'kmaq.

- Scott, Shawn; Scott, Tod (2008). "Noel Doiron and the East Hants Acadians". Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society: The Journal: 57.

- John Clarence Webster. (1933). The Career of the Abbe Le Loutre in Nova Scotia with a Translation of his Autobiography, p. 46.

- Lockerby, Earle (Spring 1998). "The Deportation of the Acadians from Ile St.-Jean, 1758". Acadiensis. XXVII (2): 45–94., para 43

- Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Daudin, Henri". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Sources

- Primary Texts

- Séminaire des missions étrangères (1764). Mémoire pour les sieurs Girard, Manach, & Le Loutre, missionnaires du Séminaire des missions étrangères dans les Indes occidentales, appellans comme d'abus : contre les Supérieur & directeurs du Séminaire des missions étrangères (in French). De l'imprimerie de Michel Lambert. ISBN 9780665521652.

- Séminaire des missions étrangères (1764). Conclusions motivées: Me Bontoux, avocat de Jacques Girard & Jean Manach, appellants comme d'abus et Jean-Louis Le Loutre, intervenant ... contre les sieurs Lalane, Burguerieux, Dufau & Conforts, supérieur & directeurs du Séminaire des Missions etrangeres, intimés (in French). De l'imprimerie de Michel Lambert. ISBN 9780665285486.

- Secondary sources

- Casgrain, Henri-Raymond (1897). Les Sulpiciens et les prêtres des Missions-Etrangères en Acadie, 1676-1762 (in French). Québec: Pruneau & Kirouac. ISBN 9780665005305.

- David, Albert (1931). "Une Autobiographie de l'Abbé Le Loutre" (PDF). Nova Francia (in French). Paris. 6: 1–34.

- Deveau, J. Alphonse (1984). L'Abbe Le Loutre et les Acadiens (in French). Agincourt, Ontario: La Societe Canadienne du Liver. ISBN 978-0-7725-5406-2.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.

- Finn, Gérard (16 December 2013). "Jean-Louis Le Loutre". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Goyau, Georges (1936). "Le Père des Acadiens: Jean-Louis Le Loutre: Missionnaire en Acadie". Revue d'histoire des missions. 13 (4): 481–513.

- Koren, Henry J. (1962). Knaves or Knights? A History of the Spiritan Missionaires in Acadia, 1732-1839. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Duquesne University Press.

- Lockerby, Earle (Spring 1998). "The Deportation of the Acadians from Ile St.-Jean, 1758". Acadiensis. XXVII (2): 45–94.

- O'Neill, Arthur Barry (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Rogers, Normand (June 1930). "The Abbe Le Loutre". Canadian Historical Review. 11 (2): 105–128. doi:10.3138/CHR-011-02-03. S2CID 162279220.

- Ségalen, Jean (2002). Acadie en résistance: Jean-Louis Le Loutre, 1711-1772 : un abbé breton au Canada français (in French). Skol vreizh. ISBN 978-2-911447-63-1.

- Soucoup, Dan (6 October 2001). "Acadia's Military Priest". Times & Transcript. Moncton, New Brunswick. pp. F3–F4.

- Webster, John Clarence (1933). The Career of the Abbe Le Loutre in Nova Scotia: With a Translation of His Autobiography. Shediac, New Brunswick.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Video - Abbe Le Loutre

- History of Nova Scotia - Abbé Le Loutre, BluPete

- "Abbe Jean-Louis Le Loutre", Daniel Paul Website, Mi'kmaq Account