John Sherman Cooper

John Sherman Cooper (August 23, 1901 – February 21, 1991) was an American politician, jurist, and diplomat from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served three non-consecutive, partial terms in the United States Senate before being elected to two full terms in 1960 and 1966. He also served as U.S. Ambassador to India from 1955 to 1956 and U.S. Ambassador to East Germany from 1974 to 1976. He was the first Republican to be popularly elected to more than one term as a senator from Kentucky and, in both 1960 and 1966, he set records for the largest victory margin for a Kentucky senatorial candidate from either party.

John Sherman Cooper | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Official portrait of Cooper while serving | |

| 1st United States Ambassador to East Germany | |

| In office December 20, 1974 – September 28, 1976 | |

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Brandon Grove (chargé d'affaires) |

| Succeeded by | David B. Bolen |

| United States Senator from Kentucky | |

| In office November 7, 1956 – January 3, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Humphreys |

| Succeeded by | Walter Dee Huddleston |

| In office November 5, 1952 – January 3, 1955 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas R. Underwood |

| Succeeded by | Alben Barkley |

| In office November 6, 1946 – January 3, 1949 | |

| Preceded by | William A. Stanfill |

| Succeeded by | Virgil Chapman |

| 5th United States Ambassador to India | |

| In office February 4, 1955 – April 9, 1956 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | George V. Allen |

| Succeeded by | Ellsworth Bunker |

| Member of the Kentucky House of Representatives from the 41st district | |

| In office 1928–1930 | |

| Preceded by | F. T. "Tom" Nichols |

| Succeeded by | William E. Randall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 23, 1901 Somerset, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | February 21, 1991 (aged 89) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Evelyn Pfaff

(m. 1944; div. 1947)Lorraine Rowan Shevlin

(m. 1955; died 1985) |

| Alma mater | |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 15th Corps, U.S. Third Army |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Bronze Star Medal |

Cooper's first political service was as a member of the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1927 to 1929. In 1930, he was elected county judge of Pulaski County. After a failed gubernatorial bid in 1939, he joined the U.S. Army in 1942. During World War II, he earned the Bronze Star Medal for reorganizing the Bavarian judicial system after the allied victory in Europe. While still in Germany, he was elected circuit judge for Kentucky's 28th district. He returned home to accept the judgeship, which he held for less than a year before resigning to seek election to A. B. "Happy" Chandler's vacated seat in the U.S. Senate. He won the seat by 41,823 votes, the largest victory margin by any Republican for any office in Kentucky up to that time.

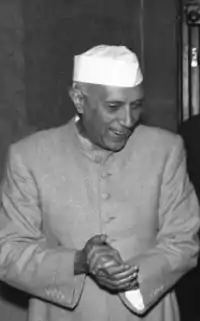

During his first term in the Senate, Cooper voted with the majority of his party just 51% of the time. He was defeated in his re-election bid in 1948, after which he accepted an appointment by President Harry S. Truman as a delegate to the United Nations General Assembly and served as a special assistant to Secretary of State Dean Acheson during the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Cooper was again elected to a partial term in the Senate in 1952. The popular Cooper appeared likely to be re-elected in 1954 until the Democrats nominated former Vice President Alben W. Barkley. Cooper lost the general election and was appointed Ambassador to India by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1955. Cooper gained the confidence of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and dramatically improved relations between the U.S. and the recently independent state of India, helping rebuff Soviet hopes of expanding communism in Asia. Barkley died in 1956, and Eisenhower requested that Cooper seek Barkley's open seat. Cooper reluctantly acquiesced and was elected to serve the rest of Barkley's term.

In 1960, Cooper was re-elected, securing his first full, six-year term in the Senate. Newly elected President John F. Kennedy – Cooper's former Senate colleague – chose Cooper to conduct a secret fact-finding mission to Moscow and New Delhi. Following Kennedy's assassination in November 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Cooper to the Warren Commission to investigate the assassination. Cooper soon became an outspoken opponent of Johnson's decision to escalate U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War, consistently advocating negotiation with the North Vietnamese instead. After Cooper's re-election in 1966, he worked with Idaho Democrat Frank Church on a series of amendments designed to de-fund further U.S. military operations in the region. These amendments were hailed as the first serious attempt by Congress to curb presidential authority over military operations during an ongoing war. Aging and increasingly deaf, Cooper did not seek re-election in 1972. His last acts of public service were as Ambassador to East Germany from 1974 to 1976 and as an alternate delegate to the United Nations in 1981. He died in a Washington, D.C., retirement home on February 21, 1991, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life

John Sherman Cooper was born August 23, 1901, in Somerset, Kentucky.[1] He was the second child and first son of seven children born to John Sherman and Helen Gertrude (Tartar) Cooper.[2] The Cooper family had been prominent in the Somerset area since brothers Malachi and Edward Cooper migrated from South Carolina along the Wilderness Trail and through the Cumberland Gap around 1790, shortly after Daniel Boone.[3] His father's parents – staunch Baptists – were active in the anti-slavery movement in the nineteenth century, and the elder John Sherman Cooper (called "Sherman") was named after the Apostle John and William Tecumseh Sherman, a hero of the Union in the Civil War.[4] The family was very active in local politics; six of Cooper's ancestors, including his father, were elected county judges in Pulaski County, and two had been circuit judges.[5] Sherman Cooper engaged in numerous successful business ventures and was known as the wealthiest man in Somerset.[6][7] At the time of John Sherman Cooper's birth, his father was serving as collector of internal revenue in Kentucky's 8th congressional district, a position to which he had been appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt.[8]

During his youth, Cooper worked delivering newspapers, in railroad yards, and in his father's coal mines in Harlan County.[9] Despite having formerly served as county school superintendent, Cooper's father had a low opinion of the public schools, and until he was in the fifth grade, Cooper was privately tutored by a neighbor.[8][10] While his father was away on business in Texas, his mother sent him to sixth grade at the public school, which he attended thereafter.[5] At Somerset High School, he played both basketball and football.[9] After the outbreak of World War I, Cooper joined an informal military training unit at the high school.[11] Two of the school's instructors organized the boys into two companies, but Cooper, who was given the rank of captain, later recalled that "they taught us how to march and that's about all."[11] During his senior year, Cooper served as class president and class poet.[9] In 1918, he graduated second in his high school class and was chosen to give the commencement speech.[5][9]

After graduation, Cooper matriculated at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky.[12] While at Centre, Cooper was accepted into the Beta Theta Pi fraternity.[13] He also played defensive end on the Praying Colonels' football team.[14] Cooper was a letterman on the team, playing alongside football notables Bo McMillin, Red Roberts, Matty Bell, and Red Weaver.[14] Another member of the team, John Y. Brown Sr., would later become one of Cooper's political rivals.[14] Coached by Charley Moran, the team was undefeated in four games in the 1918 season, which was shortened by an outbreak of the Spanish flu.[14]

Although Centre was known as one of Kentucky's foremost colleges, Cooper's father wanted him to broaden his education and, after one year at Centre, Cooper transferred to Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut.[15] At Yale, he was a classmate of his future U.S. Senate colleague, Stuart Symington.[15] Cooper was active in many extracurricular activities at Yale, including the Sophomore German Committee, the Junior Promenade Committee, the Student Council, the Class Day Committee, the Southern Club, the University Club, and Beta Theta Pi.[16] A member of the Undergraduate Athletic Association, he played football and basketball, becoming the first person in Yale history to be named captain of the basketball team in his junior and senior years.[9] In his senior year, he was accepted into the elite Skull and Bones society but regretted not being accepted into Phi Beta Kappa.[15] Upon graduation, he was voted most popular and most likely to succeed in his class.[13]

Cooper earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale in 1923 and enrolled at Harvard Law School later that year.[12] During the summer break of 1924, he returned to Kentucky, where his father, dying of Bright's disease, told him that he would soon become the head of the family, and that most of the family's resources had been lost in the economic recession of the early 1920s.[5][17] Cooper returned to Harvard after his father's death, but soon discovered that he could not simultaneously pursue a law degree and manage his family's affairs.[5] He was admitted to the bar by examination in 1928 and opened a legal practice in Somerset.[1] Over the next 20 years, he sold his father's remaining assets, paid off the family debts, and financed a college education for his six siblings.[6]

Early political career

After being urged into politics by his uncle, Judge Roscoe Tartar, Cooper ran unopposed for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives as a Republican in 1927.[9] As a member of the House, he was one of only three Republicans to oppose Republican Governor Flem D. Sampson's unsuccessful attempt to politicize the state department of health; the measure failed by a single vote.[12][18] Cooper supported the governor's plan to provide free textbooks for the state's school children and sponsored legislation to prohibit judges from issuing injunctions to end labor strikes, although the latter bill did not pass.[9][12]

In 1929, Cooper declared his candidacy for county judge of Pulaski County.[19] His opponent, the incumbent, was the president of Somerset Bank and the former law partner of Cooper's father.[19] Cooper won the election, however, beginning the first of his eight years as county judge.[19] During his service, he was required by law to enforce eviction notices, but often helped those he evicted find other housing or gave them money himself, earning him the nickname "the poor man's judge".[9] He reportedly became so depressed by the poverty and suffering of his constituents during the Great Depression that he had a nervous breakdown and took a leave of absence to seek psychiatric treatment.[9]

Cooper served on the board of trustees for the University of Kentucky from 1935 to 1946.[1] In 1939, he sought the Republican gubernatorial nomination.[12] As a result of a mandatory primary election law passed in 1935, the Republican nominee would not be chosen by a nominating convention, as was typical for the party.[7] Cooper garnered only 36% of the vote in the primary, losing the nomination to King Swope, a Lexington circuit court judge and former congressman.[7]

Service in World War II

Although well above the draft age at 41 years old, Cooper enlisted for service in the United States Army in World War II in 1942.[1] Immediately offered an officer's commission, he chose instead to enlist as a private.[20] After basic training, he enrolled in Officer Candidate School at the Fort Custer Training Center in Michigan.[9] He studied military government and graduated second in his class of 111 students.[6][21] In 1943, he was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the XV Corps of General George Patton's Third Army as a courier in the military police.[22] Cooper served in France, Luxembourg, and Germany.[12] After liberating the Buchenwald concentration camp, Patton ordered the entire population of the nearby city of Weimar to go through it and observe the conditions; Cooper also viewed the camp at that time.[23]

Following the cessation of hostilities, Cooper served as a legal advisor for the 300,000 displaced persons in his unit's occupation zone seeking repatriation after being brought to Germany as slaves by the Nazis.[9] Under the terms of the agreement reached at the Yalta Conference, all displaced Russian nationals were to be returned to the Soviet Union, but Soviet negotiators decided that the agreement did not apply to non-Russian spouses and children of the nationals.[9] Cooper brought this to the attention of General Patton, who rescinded the repatriation order in the Third Army's occupation zone.[9] Cooper received a citation from the Third Army's military government section for his action.[24] Cooper also oversaw the reorganization of the 239 courts in the German state of Bavaria in an attempt to replace all the Nazi officials, for which he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal.[9] Among the judges installed by Cooper were Wilhelm Hoegner, future Minister-President of Bavaria, and Ludwig Erhard, the future Chancellor of Germany.[25]

In 1943 or 1944, while he was still in the Army, Cooper married a nurse named Evelyn Pfaff.[6][12] Cooper was elected without opposition as circuit judge of Kentucky's twenty-eighth judicial district in 1945, despite still being in Germany and not campaigning for the office.[9] He was discharged from the Army with the rank of captain in February 1946 and returned to Kentucky to assume the judgeship.[21]

First term in the Senate and early diplomatic career

Cooper's judicial district included his native Pulaski County, as well as Rockcastle, Wayne and Clinton counties.[9] During his tenure, blacks were allowed to serve on trial juries in the district for the first time.[12] Of the first 16 opinions he issued during his time on the bench, 15 were upheld by the Kentucky Court of Appeals, Kentucky's court of last resort at the time.[26]

Cooper resigned his judgeship in November 1946 to seek the U.S. Senate seat vacated when A. B. "Happy" Chandler resigned to accept the position of Commissioner of Baseball.[12] Cooper's opponent, former Congressman and Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives John Y. Brown Sr., was better known and widely believed to be the favorite in the race.[21] However, Brown had alienated Chandler's supporters in the Democratic Party during a hotly contested senatorial primary between Brown and Chandler in 1942, and this group worked against his election in 1946.[21] Further, the Louisville Courier-Journal opposed Brown because of his attacks on former Senator J. C. W. Beckham and Judge Robert Worth Bingham, who were heads of a powerful political machine in Louisville.[21] With these two factors working against Brown, Cooper won the election to fill Chandler's unexpired term by 41,823 votes, the largest victory margin by any Republican for any office in Kentucky up to that time.[12][21] His victory marked only the third time in Kentucky's history that a Republican had been popularly elected to the Senate.[27] The move to Washington, D.C. proved to be too much for Cooper's already strained marriage.[28] In 1947, he filed for divorce, charging abandonment.[9]

Cooper described himself as "a truly terrible public speaker" and rarely made addresses from the Senate floor.[6] He was known as an independent Republican during his career in the Senate.[6] In the first roll-call vote of his career, he opposed transferring investigatory powers to Republican Owen Brewster's special War Investigating Committee.[5] His second vote, directing that proceeds from the sale of war surplus materiel be used to pay off war debts, also went against the majority of the Republican caucus, prompting Ohio Republican Robert A. Taft to ask him "Are you a Republican or a Democrat? When are you going to start voting with us?"[29] Cooper responded, "If you'll pardon me, I was sent here to represent my constituents, and I intend to vote as I think best."[6]

A few days after being sworn in, Cooper co-sponsored his first piece of legislation, a bill to provide federal aid for education.[9] The bill passed the Senate, but not the House.[9] Cooper was made chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Public Roads, and helped draft a bill authorizing $900 million in federal funds to states for highway construction.[9] In 1948, he sponsored a bill to provide price support for burley tobacco at 90 percent of parity.[12] He insisted on an amendment to the War Claims Act of 1948 that benefits to veterans injured as prisoners of war of the Germans and Japanese during World War II be paid immediately using enemy assets.[9] He also co-sponsored legislation allowing hundreds of thousands of people displaced by the Nazis to enter the United States legally.[9] He opposed bans on industrywide collective bargaining for organized labor and on the establishment of closed shops.[9] He voted against putting union welfare funds under government control, but helped to pass an amendment forbidding compulsory union membership for workers.[9]

Cooper continued his independence from his party throughout his term, vocally opposing Republican plans to cut taxes despite record national budget deficits and resisting the party's efforts to reduce funding for the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe in the aftermath of the war.[9] He worked with fellow Kentuckian Alben Barkley and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse to undermine Jim Crow laws enacted by the states and remove obstacles to suffrage for minorities.[30] He also co-sponsored a bill to create the Medicare system, although it was defeated at the time.[30] Although he had voted with the Republicans just 51% of the time during his partial term – the lowest average of any member of the party – Cooper headed the Kentucky delegation to the 1948 Republican National Convention.[9][31] He supported Arthur Vandenberg for president, but Thomas E. Dewey ultimately received the party's nomination.[31] Cooper himself was mentioned as a possible candidate for vice-president, but ultimately did not receive the nomination and sought re-election to his Senate seat instead.[9] Also in 1948, Centre College awarded Cooper an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.[32]

Cooper was opposed in his re-election bid by Democratic Congressman Virgil M. Chapman, an ally of Earle C. Clements, who had been elected governor in 1947.[33] As one of only a few Democrats who had voted in favor of the Taft–Hartley Act, Chapman had lost the support of organized labor, a key constituency for the Democrats.[33] The Democratic-leaning Louisville Times endorsed Cooper, but the presence of Kentucky's favorite son, Alben Barkley, on the ballot as Harry S. Truman's running mate in the 1948 presidential election ensured a strong Democratic turnout in the state.[33][34] Both Barkley and Clements stressed party unity during the campaign, and although Cooper polled much better than the Republican presidential ticket, he ultimately lost to Chapman in the general election by 24,480 votes.[35]

Following his defeat, Cooper resumed the practice of law in the Washington, D.C. firm of Gardner, Morison and Rogers.[12] In 1949, President Truman appointed Cooper as one of five delegates to the United Nations (U.N.) General Assembly.[9] He was an alternate delegate to that body in 1950 and 1951.[12] Secretary of State Dean Acheson chose Cooper as his advisor to meetings that created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and at meetings of the NATO Council of Ministers in London in May 1950 and Brussels in December 1950.[36] Political historian Glenn Finch observed that, while Cooper was well-qualified for his duties at the U.N. and NATO, his presence abroad also made him less available to campaign for the Senate seat vacated by Barkley's elevation to the vice-presidency.[37] Speculation was raised that Clements, who won Barkley's old seat in a special election in 1950, may have influenced Truman and Acheson to make the appointments.[37]

Second term in Senate

Cooper's supporters believed he would again seek the governorship of Kentucky or be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States in the early 1950s; some even formed a committee to elect Cooper president.[9] Cooper considered running for governor in 1951, but when Chapman was killed in an automobile accident on March 8, 1951, he decided to make another run for the Senate against Thomas R. Underwood, Governor Lawrence Wetherby's appointee to fill the vacancy.[37] Underwood was considered a heavy favorite in the race. Some Republicans faulted Cooper for taking an appointment from Democrat Truman.[38] Both the Louisville Times and the Louisville Courier-Journal recanted their statements in 1950 for Cooper to seek election to the Senate in 1954. They now feared that the election of a Republican would allow that party to organize the Senate, giving key committee chairmanships to isolationists opposed to continued US involvement in the Korean War.[39] Nevertheless, Cooper defeated Underwood by 29,000 votes in the election and served out the remainder of Chapman's term.[40] His victory marked the first time in Kentucky's history that a Republican had been elected to the Senate more than once.[41]

Cooper was named to the Senate Committee on Labor, Education and Public Welfare and chaired its education and labor subcommittees.[9] He sponsored a bill authorizing public works projects along the Big Sandy River, including the Tug and Levisa forks.[9] He also supported the reconstruction of the locks and dams along the Ohio River and the construction of locks, dams, and reservoirs in the Green River Valley.[9] He opposed the Dixon-Yates contract, which would have paid a private company to construct a new power station to generate power for the city of Memphis, Tennessee, calling instead for authorization for the Tennessee Valley Authority to issue bonds to finance the construction of new power stations.[42] He supported a comprehensive program benefiting the coal industry and cosponsored a bill to extending public library services to rural areas.[9]

Cooper continued to be an independent voice in the Senate. During the Red Scare, he was critical of attempts to permit illegal wiretap evidence in federal courts and attempts to reduce the protections against self-incrimination granted by the Fifth Amendment.[43] Nevertheless, he refused to strip Joseph McCarthy, the leading figure in the Red Scare, of his major Senate committee chairmanships, cautioning that "many of those who bitterly oppose Senator McCarthy call for the same tactics that they charge him with."[44] He was the only Republican to oppose the Bricker Amendment, which would have limited the president's treaty-making power. He concluded that the issues addressed by the amendment were not sufficient to warrant a change to the Constitution.[45] He also opposed the Submerged Lands Act and the Mexican Farm Labor bill, both of which were supported by the Eisenhower administration.[46] He denounced Eisenhower's appointment of Albert M. Cole, an open opponent of public housing, as Federal Housing Administrator and opposed many of the agricultural reforms proposed by Eisenhower's Agriculture Secretary, Ezra Taft Benson.[5] Again, his independence did little to diminish his stature in the party. In 1954, he was named to the Senate Republican Policy Committee.[9]

Cooper again sought re-election in 1954.[12] Democrats first considered Governor Wetherby as his opponent, but Wetherby's candidacy would have drawn a primary challenger from the Happy Chandler faction of the Democratic Party, possibly leading to a party split and Cooper's re-election.[47] Instead, party leaders convinced former Vice President Barkley, now 77 years old, to run for the seat in order to ensure party unity.[47] There were few policy differences between Barkley and Cooper, who had been deemed the most liberal Republican in the Senate by Americans for Democratic Action.[47][48] During the campaign, Cooper was featured on the cover of Time on July 5, 1954.[9] Cooper appealed to women voters, as well as black voters who appreciated his support for civil rights.[49] He also claimed that he would be a less partisan senator than Barkley.[50] Barkley's personal popularity carried him to a 71,000-vote victory, however.[47] Glenn Finch opined that "Barkley was unbeatable in his own state, and it is probable that no other candidate could have defeated Cooper."[47]

Ambassador to India

In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower nominated Cooper as U.S. Ambassador to India and Nepal.[12] During his time as a delegate for the United Nations, Cooper had met Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and established a cordial working relationship with the Indian delegation, including Nehru's sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.[51] The Indians had been impressed with Cooper and the Indian government had expressed their desire that Cooper serve as their ambassador from the U.S.[51] Cooper initially rejected the position offered by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles but was convinced to accept it by a personal request from President Eisenhower.[51]

India had only become an independent nation in 1947, and it was considered a bulwark against Communism in Asia.[47] U.S.–India relations were strained, however, because of India's recognition of Communist China, its opposition to the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), and its resistance to foreign interference in Indochina.[47] U.S. News & World Report described the ambassadorship as "one of the most difficult and delicate in all the diplomatic world".[48]

Cooper married Lorraine Rowan Shevlin on March 17, 1955, in Pasadena, California, just ten days before leaving for India.[9][52] Twice divorced, Shevlin was the daughter of Robert A. Rowan (a wealthy California real estate developer whose projects included the Hotel Alexandria and the Security Building), step-daughter of Vatican official Prince Domenico Orsini, and a well-known socialite.[28] She was fluent in three languages and understood Russian.[52] The two had dated for much of the 1950s, but Cooper was hesitant to marry because he had doubts about moving into Shevlin's elaborate Georgetown home.[53] (While in Washington, the unmarried Cooper permanently resided in the Dodge House Hotel.)[54] The move to India removed this barrier, and Secretary Dulles encouraged Cooper to marry her before leaving so that the embassy in New Delhi might have a proper hostess.[55] On April 4, 1955, the couple stopped in England on their way to India to visit with Louis Mountbatten, the last Governor-General of India.[56] Their discussions about the situation of the Indian situation were part of the scant preparation Cooper received before arriving there.[56]

Cooper began his service as ambassador by developing a close friendship with Prime Minister Nehru.[57] Nehru's respect and admiration for Cooper soon became widely known.[58] Cooper labored to help officials in Washington, D.C. understand that India's reluctance to align with either the West or the Communists in China and the Soviet Union was their way of exercising their newly won independence.[59] At the same time, he defended the U.S. military buildup after World War II, its involvement in the Korean War, and its membership in mutual security pacts like NATO and SEATO as self-defense measures, not aggressive actions by the U.S. government, as the Indians widely perceived them.[60] Cooper condemned the Eisenhower administration's decision to sell weapons to Pakistan, which was resented by the Indians, but also felt that the Indian government took some political positions without regard to their moral implications.[60] By late 1955, the Chicago Daily News reported that Indo-American relations had "improved to a degree not thought possible six months ago".[61]

In a joint communique dated December 2, 1955, U.S. Secretary of State Dulles and Portuguese Foreign Minister Paulo Cunha condemned statements made by Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin and Soviet Party First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev during an eighteen-day tour of India.[61] Of particular interest was the communique's reference to "Portuguese provinces in the Far East".[62] This phrase referred to Goa, a Portuguese colony in western India.[62] Although most European nations with holdings near India had granted them to the new independent nation in 1947, Portugal refused to surrender Goa, and the region had become a source of conflict between the two nations.[63] The joint communiqué seemed to indicate U.S. recognition of Portuguese sovereignty in Goa, which undercut Cooper's assurances to the Indians of U.S. neutrality in the matter.[62] Cooper himself did not know about the communiqué until he read an account of it in the Indian media and was therefore unprepared to offer an explanation for it when asked by the Indian Foreign Secretary.[62] Cooper's cable to Washington, D.C. about the matter was reported to have been "bitter", although the contents of the cable have not been released.[62]

The Dulles–Cuhna communique touched off anti-American demonstrations in many parts of India.[62] On December 6, Dulles held a news conference during which he reaffirmed U.S. neutrality on the Goa issue, but did not recant claims of Portuguese sovereignty over the region.[64] Prime Minister Nehru announced his intent to file a formal protest with the United States over the communique and to address the Indian Parliament about the matter.[65] In the interim, Cooper secured a meeting with Nehru and forestalled both actions.[66] Cooper became even more upset with Dulles when Dulles authorized withholding $10 million of a $50 million aid package to India; Cooper protested the withholding, and Dulles decided to pay the full amount.[67]

Throughout the early part of 1956, Cooper strongly advocated that the U.S. respect Indian nonalignment and increase economic aid to the country.[68] In August 1956, Congress approved a financial aid package for India that included the largest sale up to that point of surplus agricultural products by the United States to any country.[69] Cooper's persistence in requesting such aid was critical in getting the package approved, as it was opposed by many administration officials, including Under Secretary of State Herbert Hoover Jr., Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey, and International Cooperation Administration Director John B. Hollister.[69]

Later service in the Senate

Senator Barkley died in office on April 30, 1956.[70] Republican leaders encouraged Cooper to return from India and seek the seat, but Cooper was reluctant to give up his ambassadorship.[70] After a personal appeal from President Eisenhower, however, Cooper acquiesced and declared his candidacy in July 1956.[70] Even after leaving India, he maintained close ties with the country's leaders and was the official U.S. representative at the funerals of Prime Minister Nehru in 1964, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri in 1966, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984.[9]

Because Barkley's death occurred after the filing deadline for the November elections, the Democratic State Central Committee had to choose a nominee for the now-open seat.[70] After unsuccessfully attempting to find a compromise candidate that both the Clements and Chandler factions could support, they chose Lawrence Wetherby, whose term as governor had recently expired.[70] Chandler, now serving his second term as governor, was angered by the choice of Wetherby, and most members of his faction either gave Wetherby lukewarm support or outright supported Cooper instead.[71] This, combined with Cooper's personal popularity, led to his victory over Wetherby by 65,000 votes.[71]

Upon his return to the Senate in 1957, Cooper was assigned to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[72] In 1959, he challenged Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen to become the Republican floor leader in the Senate, but lost by four votes.[6] In a 1960 poll of fifty journalists conducted by Newsweek magazine, Cooper was named the ablest Republican member of the Senate.[12] He helped author and co-sponsored the National Defense Education Act.[9] Together with Senator Jennings Randolph, he sponsored the Appalachian Regional Development Act, designed to address the prevalent poverty in Appalachia.[12] He succeeded in gaining more state and local control over the anti-poverty group Volunteers in Service to America.[73] He was a vigorous opponent of measures designed to weaken the Tennessee Valley Authority.[12]

In 1960, Democrats nominated former governor Keen Johnson, then an executive with Reynolds Metals, to oppose Cooper's re-election bid.[71] Cooper had the support of organized labor and benefitted from a large segment of Kentuckians who voted for Republican Richard M. Nixon over Democrat John F. Kennedy as a reaction against Kennedy's Catholicism in the 1960 presidential election.[74] Cooper ultimately defeated Johnson by 199,257 votes, a record victory margin for a Kentucky senatorial candidate.[75]

Shortly after his election as president in 1960, Kennedy chose Cooper to conduct a then-secret mission to Moscow and New Delhi to assess the attitudes of the Soviet government for the new administration.[76] Kennedy and Cooper had served together on the Senate Labor Committee and maintained a social friendship.[77] On the mission, Cooper discovered that the Soviets disliked Kennedy and Nixon equally.[77] Cooper concluded in his report to Kennedy that there was little potential for harmonious relations with the Soviets.[77] After meeting with Secretary Khrushchev, Kennedy confirmed to Cooper that his report had been correct and confessed that he should have taken it even more seriously.[77] Cooper supported Kennedy's decision to resume nuclear weapons testing after the Soviets resumed their testing in March 1962, but he urged Kennedy to negotiate an agreement with the Soviets if possible.[78]

President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Cooper to the Warren Commission, which was charged with investigating Kennedy's assassination in 1963.[12] Cooper attended 50 of the 94 hearings and rejected the single-bullet theory stating that "there was no evidence to show that [Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally] were hit by the same bullet."[79] Cooper publicly criticized the report's conclusions as "premature and inconclusive", and informed Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy that he strongly felt Lee Harvey Oswald had not acted alone. When Cooper expressed his same thoughts to Jacqueline Kennedy, he reportedly stated that "it's important for this nation that we bring the true murderers to justice."[80]

As one of three Republicans on the Senate Rules and Administration Committee, Cooper was involved with the investigation of Johnson aide Bobby Baker in 1964, which he decried as "a whitewash" after the committee blocked further investigation.[73] He proposed the establishment of a Senate Select Committee on Standards and Conduct in July 1964 and was named to that committee in July 1965.[73] Also in 1965, he was chosen advisor to the United States delegation to the Manila Conference that established the Asian Development Bank.[13]

An advocate for small businesses and agricultural interests, Cooper opposed an April 1965 bill that expanded the powers of the Federal Trade Commission to regulate cigarette advertising.[73] In March 1966, he proposed an amendment to a mine safety bill supported by the United Mine Workers of America that would have nullified provisions of the bill if they were not shown to contribute to the safety of small mines, but his amendment was defeated.[73]

Cooper voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957,[81][82] 1960,[83] 1964,[84] and 1968,[85] as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,[86] the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[87][88] and the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court.[89] Cooper was one of thirteen Republican senators to vote in favor of Medicare.[90]

Opposition to the Vietnam War

| U.S. Congressional opposition to American involvement in wars and interventions |

|---|

| 1812 North America |

| House Federalists’ Address |

| 1847 Mexican–American War |

| Spot Resolutions |

| 1917 World War I |

| Filibuster of the Armed Ship Bill |

| 1935–1939 |

| Neutrality Acts |

| 1935–1940 |

| Ludlow Amendment |

| 1970 Vietnam |

| McGovern–Hatfield Amendment |

| 1970 Southeast Asia |

| Cooper–Church Amendment |

| 1971 Vietnam |

| Repeal of Tonkin Gulf Resolution |

| 1973 Southeast Asia |

| Case–Church Amendment |

| 1973 |

| War Powers Resolution |

| 1974 |

| Hughes–Ryan Amendment |

| 1976 Angola |

| Clark Amendment |

| 1982 Nicaragua |

| Boland Amendment |

| 2007 Iraq |

| House Concurrent Resolution 63 |

| 2018–2019 Yemen |

| Yemen War Powers Resolution |

Although Cooper voted in favor of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, he opposed escalating U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.[91] As early as April 1964, Cooper was urging President Johnson to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the tensions in Southeast Asia.[92] He questioned Southeast Asia's strategic importance to the U.S. and expressed concerns about the feasibility of deploying the U.S. military on a global scale.[93] On March 25, 1965, he joined New York Senator Jacob Javits in a call for President Johnson to begin negotiations for a settlement between North Vietnam and South Vietnam without imposing preconditions on the negotiations.[94] Later in the day, he introduced resolutions calling for Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to brief the full Senate on recent developments in Vietnam.[95]

In January 1966, Cooper accompanied Secretary of State Rusk and Ambassador W. Averell Harriman on an official visit to Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos as part of a widely publicized "peace drive".[73] This visit, along with visits to South Vietnam in December 1965 and January 1966, reinforced Cooper's opposition to military operations in Southeast Asia.[96] In a meeting with President Johnson on January 26, 1966, he again urged the president to forgo his announced intentions to resume bombing missions in North Vietnam and negotiate a settlement instead.[96] Johnson was noncommittal, and that afternoon, Cooper returned to the Senate floor, urgently trying to convince the legislators that negotiation was preferable to escalation, even when it meant negotiating with the Viet Cong fighters in South Vietnam, which he believed was necessary to achieve peace.[97] Cooper advocated a three-to-five-year cease fire, enforced by the United Nations, followed by national elections as prescribed by the 1954 Geneva Convention.[97] Ultimately, Johnson did not heed Cooper's plea and resumed U.S. bombing missions in North Vietnam.[98]

In 1966, Cooper again won re-election over John Y. Brown Sr., by 217,000 votes, breaking his own record of largest victory margin for a Kentucky senatorial candidate, and carrying the vote of 110 of Kentucky's 120 counties.[9][27] In the lead-up to the 1968 Republican presidential primary, he endorsed New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, saying that Americans would only support a candidate who took a clear position on Vietnam.[99] Rockefeller had laid out a plan for reversing the Americanization of the war, while other Republican candidates tried to remain non-specific about how they would handle it.[100] As Rockefeller's candidacy faded, Cooper encouraged his colleague, Kentucky Senator Thruston B. Morton, to seek the presidency, but Morton declined.[101] The Republican nomination – and the presidency – went to Richard Nixon.[101]

As a delegate to the U.N. General Assembly in 1968, Cooper strongly denounced the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.[102] He also supported Montana Senator Mike Mansfield's proposal to bring the matter of the Vietnam War before the United Nations.[73] Returning to the Senate in 1969, he joined Alaska Senator Ernest Gruening and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse in protesting restrictions on orderly protests at the United States Capitol.[73]

In the Senate, Cooper helped lead the opposition to the development and deployment of anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs), putting him at odds with many in his party, including President Nixon.[101] Cooper had long been an opponent of ABMs, which he believed could intensify a worldwide nuclear arms race.[101] On August 6, 1969, a vote to suspend funding of the development of ABMs failed in the Senate by a vote of 50–51; Vice President Spiro Agnew cast the tie-breaking vote.[101] After this defeat, Cooper and Michigan Senator Philip Hart co-sponsored the Cooper–Hart Amendment that would have allowed funding for research and development of ABMs, but banned deployment of a U.S. ABM system.[9] The measure failed by three votes but increased congressional scrutiny of the Defense Department budget, leading to a reduction in funding and hastening Strategic Arms Limitation Talks with the Soviets.[103] Cooper served as an advisor to President Nixon during the events leading up to the talks.[9]

Throughout 1969 and 1970, Cooper and Senator Frank Church co-sponsored the Cooper–Church Amendments, aimed at curbing further escalation of the Vietnam War.[104] Congressional approval of one of these amendments on December 15, 1969, de-funded the use of U.S. troops in Laos and Thailand.[105] Cooper had wanted to include a restriction on forces entering Cambodia as well, but Mike Mansfield, who helped Cooper write the amendment, feared that Cambodian Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who was officially neutral in the conflict, might be offended.[105] When Sihanouk was deposed in 1970, Cambodia's new leader, Lon Nol, appealed to President Nixon for help in stabilizing his rule.[105] Nixon agreed to send troops to Cambodia, despite protests from Cooper and others that this violated his stated goal of de-escalation in the region.[105] Cooper and Church then drafted another amendment to de-fund U.S. operations in Cambodia; after negotiations with Nixon that continued funding until July 1970 so that the troops already in the country could be evacuated, the amendment passed 58–37.[106] The House of Representatives later stripped the amendment from the legislation to which it was attached, and it did not go into effect.[107] The amendment was nevertheless hailed by The Washington Post as "the first time in our history that Congress has attempted to limit the deployment of American troops in the course of an ongoing war."[107] The fight over the Cooper–Church Amendments took its toll on Cooper's health, and he was briefly hospitalized to regain his strength.[107] In 1971, Church, Mansfield, and George Aiken convinced Cooper to help them write an amendment to end U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia altogether, but ultimately, the measure did not have the support to pass and was abandoned.[107]

Seventy-one years of age and becoming increasingly deaf, Cooper announced to the Kentucky Press Association on January 21, 1972, that he would not seek re-election to his Senate seat,[108] having served longer in that body than any other Kentuckian except Alben Barkley.[27] The lame duck Cooper decided to make one more attempt to end the war, after an aggressive North Vietnamese offensive against the South in March 1972 intensified fighting in the region once again.[109] Without advance notice, Cooper addressed a nearly empty Senate chamber on July 27, 1972, proposing an amendment to a military assistance bill that would unconditionally end funding for all U.S. military operations in Indochina in four months.[109] The measure, which had no co-sponsors, stunned Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and provoked heated debate in the Senate.[109] Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke saved the amendment from almost certain demise by adding a provision that all American prisoners of war be returned prior to the withdrawal of U.S. forces.[109] The revised amendment passed 62–33, whereupon Nixon decided to sacrifice the entire military assistance bill.[109] At Nixon's insistence, the Senate defeated the amended bill 48–42.[110] Disappointed, Cooper nevertheless proclaimed, "I feel purged inside. I've felt strongly about this for a long time. Now it's in the hands of the President. He's the only person who can do anything about ending the war now."[110]

Later life

| External video | |

|---|---|

After the expiration of his term, Cooper took over the "Dean Acheson chair" at the prestigious Washington law firm of Covington & Burling.[112] In 1972, he was chosen as the commencement speaker at Centre College, where he had served as a trustee since 1961.[32] At the ceremony, he became the first recipient of the Isaac Shelby Award, named for two-time Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby, the chair of the college's first board of trustees.[32] In 1973, Cooper resisted an attempt to name a federal building in his honor.[9] Upon the completion of the dam that formed Laurel River Lake in 1977, Congress proposed naming the dam and lake after Cooper, but again, he declined.[9] He was pleased, however, that the Somerset school system chose to name a program to teach and reinforce leadership skills the John Sherman Cooper Leadership Institute.[9]

In April 1974, Nixon announced that he would appoint Cooper to be the US Ambassador to East Germany, but during the final negotiations between the countries for the US to establish an embassy in the country, Nixon resigned.[113] His successor, Gerald Ford, officially appointed Cooper to the ambassadorship, and Cooper took leave from Covington & Burling to accept it.[12] He arrived in East Germany in December 1974 and served as ambassador until October 1976.[12][114] After returning to the US, he resumed his work at Covington & Burling.[9] In his last act of public service, he again served as an alternate delegate to the UN General Assembly in 1981.[12]

Kentucky Governor John Y. Brown Jr., the son of Cooper's former opponent in the senatorial elections of 1946 and 1966, awarded Cooper the Governor's Distinguished Service Medallion in 1983.[9] Later that year, Senators Walter Huddleston of Kentucky and Howard Baker of Tennessee introduced a bill to honor Cooper by renaming the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area to the Cooper National Recreation Area; Kentucky Congressman Hal Rogers sponsored a parallel measure in the House.[115] As a senator, Cooper had been instrumental in securing congressional approval for the creation of Big South Fork.[115] Opponents of the measure in both Kentucky and Tennessee (the recreation area spans the two states) cited a variety of reasons to retain the old name, and the proposal was eventually dropped at Cooper's request.[9][115]

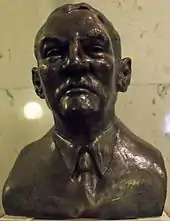

In 1985, Cooper became the third-ever recipient of the Oxford Cup, an award recognizing outstanding past members of Beta Theta Pi.[13] Also in 1985, he was awarded an honorary doctorate degree from Cumberland College (now the University of the Cumberlands) in Williamsburg, Kentucky.[116] He was named a Distinguished Alumnus of Centre College in 1987.[32] A non-partisan group co-chaired by former Kentucky gubernatorial candidate Larry Forgy raised $60,000 to commission two sculptures of Cooper.[117] A life-sized bronze bust of Cooper sculpted by John Tuska was installed at the Kentucky State Capitol in 1987.[9][117] The other sculpture, a life-sized bronze statue crafted by Barney Bright, was placed in Fountain Square in Somerset.[9][117]

Cooper retired from the practice of law in 1989.[12] In June 1990, Cooper was honored with a gala screening of Gentleman From Kentucky, a Kentucky Educational Television documentary about his life, at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington.[9] On February 21, 1991, Cooper died of heart failure in a retirement home in Washington.[6] He had been preceded in death by his second wife, Lorraine Arnold Rowan, on February 3, 1985.[12] On February 26, 1991, Kentucky's two senators, Wendell H. Ford and Mitch McConnell, gave speeches on the Senate floor praising Cooper, and the Senate adjourned in Cooper's memory.[118] Cooper was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.[1]

Because of his extensive support of rural electrification as a senator, the East Kentucky RECC was renamed the John Sherman Cooper Power Station in his honor.[13] In 1999, the Lexington Herald-Leader named Cooper one of the most influential Kentuckians of the 20th century.[119] In 2000, Eastern Kentucky University's Center for Kentucky History and Politics established the annual John Sherman Cooper Award for Outstanding Public Service in Kentucky.[120]

Despite his patrician background, Cooper was known for being "affable, frequently self-deprecating and approachable."[121]

References

- "Cooper, John Sherman". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Schulman, p. 16

- Schulman, p. 15

- Smoot, p. 134

- "Whittledycut". Time

- Krebs, "John Sherman Cooper Dies at 89"

- Finch, p. 162

- Smoot, p. 135

- Hewlett and Merrit, "John Sherman Cooper Dies at 89"

- Schulman, p. 17

- Smoot, p. 144

- Cooper, p. 227

- Howard, "John Sherman Cooper"

- Smoot, p. 146

- Schulman, p. 19

- Smoot, p. 151

- Smoot, p. 154

- Schulman, p. 21

- Schulman, p. 22

- Schulman, p. 26

- Finch, p. 163

- Schulman, p. 28

- Schulman, p. 31

- Schulman, p. 32

- Schulman, p. 33

- Schluman, p. 34

- Finch, p. 161

- Schulman, p. 67

- Schluman, p. 37

- Schulman, p. 38

- Schulman, p. 39

- "John Sherman Cooper: Centre College Class of 1922". CentreCyclopedia

- Finch, p. 164

- Schulman, p. 41

- Finch, pp. 164–165

- Schulman, pp. 43, 50–51

- Finch, p. 165

- Schulman, p. 56

- Schulman, p. 57

- Finch, p. 166

- Finch, pp. 161, 164

- Schulman, p. 63

- Schulman, p. 62

- Schulman, pp. 62–63

- Schulman, p. 60

- Schulman, p. 64

- Finch, p. 167

- Franklin, p. 29

- Schulman, p. 65

- Schulman, p. 66

- Franklin, p. 31

- Franklin, p. 32

- Schulman, p. 69

- Schulman, p. 68

- Schulman, pp. 68–69

- Franklin, p. 33

- Franklin, p. 34

- Franklin, p. 36

- Franklin, p. 37

- Franklin, p. 40

- Franklin, p. 46

- Franklin, p. 47

- Franklin, pp. 42–43

- Franklin, pp. 48–49

- Franklin, p. 49

- Franklin, p. 50

- Franklin, p. 51

- Franklin, p. 52

- Franklin, p. 53

- Finch, p. 168

- Finch, p. 169

- Schulman, p. 88

- Bluestone, p. 113

- Finch, p. 170

- Finch, pp. 161, 170

- Schulman, p. 89

- Schulman, p. 90

- Logevall, p. 243

- Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3.

- Heymann, David C. (2003). The Georgetown Ladies' Social Club : Power, Passion, and Politics in the Nation's Capital. Atria Books. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-7434-2856-0. OCLC 53222690.

- "Senate – August 7, 1957" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 103 (10): 13900. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – August 29, 1957" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 103 (12): 16478. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – April 8, 1960" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 106 (6): 7810–7811. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – June 19, 1964" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 110 (11): 14511. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – March 11, 1968" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 114 (5): 5992. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – March 27, 1962" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 108 (4): 5105. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – May 26, 1965" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 111 (2): 11752. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – August 4, 1965" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 111 (14): 19378. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Senate – August 30, 1967" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 113 (18): 24656. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- TO PASS H.R. 6675, THE SOCIAL SECURITY AMENDMENTS OF 1965

- Johns, p. 590

- Johns, p. 588

- Johns, p. 589

- Johns, p. 591

- Logevall, p. 247

- Johns, p. 592

- Logevall, p. 248

- Logevall, p. 249

- Johns, p. 608

- Johns, p. 607

- Logevall, p. 252

- Schulman, p. 95

- Schulman, pp. 97–98

- Schulman, p. 101

- Logevall, p. 254

- Logevall, pp. 254–255

- Logevall, p. 256

- Schulman, p. 103

- Logevall, p. 257

- Logevall, p. 258

- "Senator Mitch McConnell on Senator John Sherman". C-SPAN. June 30, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- Schulman, p. 105

- Schulman, pp. 105–106

- Schulman, p. 107

- Cohn, "Bill to Name Area for Cooper Opposed"

- "Kentucky Colleges Mark Commencement." Lexington Herald-Leader

- "Group Raises $60,000 for Sculptures of Cooper." Lexington Herald-Leader

- "U.S. Senate Adjourns in Memory of Cooper". Lexington Herald-Leader

- "John Sherman Cooper." Lexington Herald-Leader

- "Ex-Gov. Breathitt to Receive Award." Lexington Herald-Leader

- Hill, Ray. "The Independent From Kentucky: John Sherman Cooper". Knoxville Focus. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

Bibliography

- Bluestone, Miriam D. (2006). "Cooper, John S.". In Chester J. Pach (ed.). Presidential Profiles: The Johnson Years. New York City: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-5388-9.

- Cohn, Ray (December 8, 1983). "Bill to Name Area for Cooper Opposed". Lexington Herald-Leader. p. B1.

- Cooper, William (Spring 1986). "John Sherman Cooper: A Senator and His Constituents". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 84: 192–210.

- "Cooper, John Sherman". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- Cooper, William (1992). "Cooper, John Sherman". In John E. Kleber (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- "Ex-Gov. Breathitt to Receive Award – New Public Service Citation Honors John Sherman Cooper". Lexington Herald-Leader. October 5, 2000. p. B3.

- Finch, Glenn (April 1972). "The Election of United States Senators in Kentucky: The Cooper Period". Filson Club History Quarterly. 46: 161–178.

- Franklin, Douglas A. (Winter 1984). "The Politician as Diplomat: Kentucky's John Sherman Cooper in India, 1955–1956". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 82: 28–59. online

- "Group Raises $60,000 for Sculptures of Cooper". Lexington Herald-Leader. April 5, 1985. p. B2.

- Hewlett, Jennifer; Harry Merrit (February 23, 1991). "John Sherman Cooper Dies at 89 – U.S. Senator From Somerset Had Distinguished Political Career". Lexington Herald-Leader. p. A1.

- Howard, Robert T. "John Sherman Cooper" (PDF). Oxford Cup Roll. Beta Theta Pi. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- "John Sherman Cooper". Lexington Herald-Leader. December 31, 1999. p. 8.

- "John Sherman Cooper: Centre College Class of 1922". CentreCyclopedia. Centre College. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- Johns, Andrew L. (October 2006). "Doves Among Hawks: Republican Opposition to the Vietnam War, 1964–1968". Peace & Change. 31 (4): 585–628. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0130.2006.00392.x.

- Johns, Andrew L. "The Diplomacy of Quiet Candor: John Sherman Cooper's Tenure as Ambassador to India." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 119.1 (2021): 37–70.

- "Kentucky Colleges Mark Commencement". Lexington Herald-Leader. May 12, 1985. p. B1.

- Krebs, Albin (February 23, 1991). "John Sherman Cooper Dies at 89; Longtime Senator From Kentucky". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- Logevall, Fredrik (2003). "A Delicate Balance: John Sherman Cooper and the Republican Opposition to the Vietnam War". In Randall Bennett Woods (ed.). Vietnam and the American Political Tradition: The Politics of Dissent. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 237–258. ISBN 978-0-521-81148-4.

- Mitchiner, Clarice James (1982). Senator John Sherman Cooper: Consummate Statesman. New York City: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-14099-1.

- Schulman, Robert (1976). John Sherman Cooper: The Global Kentuckian. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0220-0.

- Smoot, Richard C. (Spring 1995). "John Sherman Cooper: The Early Years, 1901–1927". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 93: 133–158.

External links

- "John Sherman Cooper: A Featured Biography". Senate Historical Office. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- "U.S. Senate Adjourns in Memory of Cooper". Lexington Herald-Leader. February 27, 1991. p. B2.

- "Whittledycut". Time. July 5, 1954. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- Cooper on the cover of Time magazine, July 5, 1954

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with John Sherman Cooper" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Sen-Elect John S. Cooper (December 8, 1952)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive