Johnny Rivers

Johnny Rivers (born John Henry Ramistella; November 7, 1942)[1] is an American musician. His repertoire includes pop, folk, blues and old-time rock 'n' roll. Rivers charted during the 1960s and 1970s but remains best known for a string of hit singles between 1964 and 1968, among them "Memphis" (a Chuck Berry cover), "Mountain of Love" (a Harold Dorman cover), "The Seventh Son" (a Willie Mabon cover), "Secret Agent Man", "Poor Side of Town" (a US No. 1), "Baby I Need Your Lovin'" (a 1967 cover of the Four Tops single from 1964) and "Summer Rain".[2][3]

Johnny Rivers | |

|---|---|

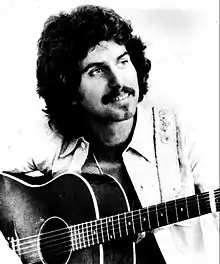

Rivers in a publicity photo in 1975 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Henry Ramistella |

| Born | November 7, 1942 New York City, U.S. |

| Origin | Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active | 1956–present |

| Labels | |

| Website | johnnyrivers |

Life and career

Early years

Rivers was born John Henry Ramistella in New York City, of Italian descent. His family moved from New York to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Influenced by the distinctive Louisiana musical style, Rivers began playing guitar at age eight, taught by his father and uncle. While still in junior high school, he started sitting in with a band called the Rockets, led by Dick Holler, who later wrote several hit songs, including "Abraham, Martin and John" and the novelty song "Snoopy vs. the Red Baron".[2][3]

Ramistella formed his own band, the Spades, and made his first record at 14 while he was a student at Baton Rouge High School.[2] Some of their music was recorded on the Suede label as early as 1956.[4]

On a trip to New York City in 1958, Ramistella met Alan Freed, who advised him to change his name to "Johnny Rivers" referencing the Mississippi River that flows through Baton Rouge.[2] Freed also helped Rivers get several recording contracts on the Gone label.[3] From March 1958 to March 1959, Johnny Rivers released three records, including "Baby Come Back" (a non-Christmas version of Elvis Presley's "Santa Bring My Baby Back (To Me)"), none of which sold well.[2]

Rivers returned to Baton Rouge in 1959 and began playing throughout the American South alongside comedian Brother Dave Gardner. One evening in Birmingham, Alabama, Rivers met Audrey Williams, Hank Williams' first wife. She encouraged Rivers to move to Nashville, Tennessee, where he found work as a songwriter and demo singer. Rivers also worked alongside Roger Miller. By this time, Rivers had decided he would never make it as a singer and songwriting became his priority.[2][3]

1960s

In 1958, Rivers met fellow Louisianan James Burton, a guitarist in a band led by Ricky Nelson. Burton later recommended one of Rivers' songs, "I'll Make Believe," to Nelson who recorded it. They met in Los Angeles in 1961, where Rivers subsequently found work as a songwriter and studio musician. His big break came in 1963 when he filled in for a jazz combo at Gazzarri's, a nightclub in Hollywood where his instant popularity drew large crowds.[2][3][5]

In 1964, Elmer Valentine gave Rivers a one-year contract to open at the Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Strip in West Hollywood.[2][5] The Whisky had been in business just three days when the Beatles song "I Want to Hold Your Hand" entered the Billboard Hot 100.[3] The subsequent British Invasion knocked almost every American artist off the top of the charts but Rivers was so popular that record producer Lou Adler decided to issue Johnny Rivers Live at the Whisky a Go Go,[2] which reached No. 12. Rivers recalled that his most requested live song then was "Memphis",[6] which reached No. 2 on Cash Box on 4–11 July 1964[7] and also on the Hot 100 on 11–18 July 1964. It sold over one million copies and was awarded a gold disc.[8] According to Elvis Presley's friend and employee, Alan Fortas, Presley played a test pressing of "Memphis" for Rivers that Presley had made but not released. Rivers was impressed and much to Presley's chagrin, Rivers recorded and released it even copying the arrangement. [9] Rivers' version far outsold the Chuck Berry original from August 1959, which stalled at No. 87 in the US.[10]

Rivers continued to record mostly live performances throughout 1964 and 1965, including Go-Go-style records with songs featuring folk music and blues rock influences including "Maybellene" (another Berry cover), after which came "Mountain of Love", "Midnight Special", "Seventh Son" (written by Willie Dixon) plus Pete Seeger's" Where Have All the Flowers Gone?", all of which were hits.[2][11]

In 1963, Rivers began working with writers P.F. Sloan and Steve Barri on a theme song for the American broadcast of a British television series Danger Man, starring Patrick McGoohan. At first Rivers balked at the idea but eventually changed his mind. The American version of the show, titled Secret Agent, went on the air in the spring of 1965. The theme song was very popular and created public demand for a longer single version. Rivers' recording of "Secret Agent Man" reached No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1966.[12] It sold a million copies also winning gold disc status.[8]

In 1966, Rivers began to record ballads that featured background vocalists. He produced several hits including his own "Poor Side of Town", which became his biggest chart hit and his only No. 1 record. He also started his own record company, Soul City Records, which included the 5th Dimension. The group's recordings of "Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In" and "Wedding Bell Blues" became No. 1 hits for the new label. In addition, Rivers is credited with giving songwriter Jimmy Webb a major break when the 5th Dimension recorded his song "Up, Up and Away".[3] Rivers also recorded Webb's "By the Time I Get to Phoenix". It was covered by Glen Campbell, who had a major hit with it.[13]

Rivers continued to record more hits covering other artists, including "Baby I Need Your Lovin'", originally recorded by the Four Tops, and "The Tracks of My Tears" by the Miracles, both going Top 10 in 1967. In 1968, Rivers put out Realization, a No. 5 album that included the No. 14 pop chart single "Summer Rain", written by a former member of the Mugwumps, James Hendricks. The album included some of the psychedelic influences of the time, like the song Hey Joe with a two-minute introduction and marked a change in Rivers' musical direction with more introspective songs including "Look to Your Soul" and "Going Back to Big Sur".[14]

1970s

In the 1970s, Rivers continued to record more songs and albums that were successes with music critics but did not sell well. L.A. Reggae (1972) reached the LP chart as a result of the No. 6 hit "Rockin' Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu," a cover version of the Huey "Piano" Smith and the Clowns song. The track became Rivers' third million seller, which was acknowledged with the presentation of a gold disc by the Recording Industry Association of America (R.I.A.A.) on January 29, 1973.[8]

Reviewing L.A. Reggae in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau said, "there are modernization moves, of course—two get-out-the-vote songs (just what George needs) plus the mysterious reggae conceit plus a heartfelt if belated antiwar song—but basically this is just Johnny nasalizing on some fine old memories. 'Rockin' Pneumonia' and 'Knock on Wood' are especially fine."[15]

Other Hot 100 top 40 hits from that time period were 1973's "Blue Suede Shoes" (originally recorded in 1955 by Carl Perkins)[4] and 1975's "Help Me Rhonda" (originally a No. 1 hit for the Beach Boys), on which Brian Wilson sang back-up vocals.

Rivers' last Top 10 entry was his 1977 recording of "Swayin' to the Music (Slow Dancing)," written by Jack Tempchin and originally released by Funky Kings. Rivers' last Hot 100 entry, also in 1977, was "Curious Mind (Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um)," originally released by Major Lance and written by Curtis Mayfield. In addition, Rivers recorded the title song for the late night concert-influenced TV show The Midnight Special.[14] His career total is nine Top 10 hits on the Hot 100 and 17 in the Top 40 from 1964 to 1977.

1980s to present

Rivers continued releasing material into the 1980s (e.g. 1980's Borrowed Time LP), garnering an interview with Dick Clark on American Bandstand in 1981,[16][17] although his recording career was winding down. Around this time, Rivers turned to Christianity.[18]

In 1998 he reactivated his Soul City Records label and released Last Train to Memphis. In early 2000, Rivers recorded with Eric Clapton, Tom Petty and Paul McCartney on a tribute album dedicated to Buddy Holly's backup band, the Crickets.[19]

He is one of a small number of performers whose names are listed as the copyright owner on their recordings. Most records list the recording company as the owner of the recording. Others include Mariah Carey, Paul Simon, Billy Joel, Pink Floyd (from 1975's Wish You Were Here onward), Queen, Genesis (though under the members' individual names and/or the pseudonym Gelring Limited), and Neil Diamond. The practice began with the Bee Gees and their $200 million lawsuit against RSO Records, the largest successful lawsuit against a record company by an artist or group.[20]

On June 12, 2009, Johnny Rivers was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.[2] His name has been suggested many times for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but he has never been selected. Rivers, however, was a nominee for 2015 induction into America's Pop Music Hall of Fame.

On April 9, 2017, he performed a song, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar, at the funeral for Chuck Berry, at The Pageant, in St. Louis, Missouri.

In 2019, Rivers announced his farewell tour.[21] His last live performance was in July 2023 at Commerce Casino near Los Angeles. E .[22]

Discography

References

- Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. pp. 2097/8. ISBN 0-85112-939-0.

- "Louisiana Music Hall of Fame – Johnny Rivers". Louisiana Music Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- "Johnny Rivers Biography". JohnnyRivers.com. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Poore, Billy (1998). Rockabilly: A Forty-Year Journey, p. 101. Hal Leonard Corporation; ISBN 0-7935-9142-2.

- Quisling, Erik, and Williams, Austin (2003). Straight Whisky: A Living History of Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll on the Sunset Strip, pp. 19–21. Bonus Books, Inc. ISBN 1-56625-197-4.

- Johnny Rivers interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- "Cash box: Top 100 singles 1964". Cashbox Magazine. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. pp. 181, 210 & 319. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- Fortas, Alan and Nash, Alanna (1992). Elvis from Memphis to Hollywood, p.228, Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-322-1.

- "Cash box: Top 100 singles 1963". Cashbox Magazine. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Price, Randy. "The 60s Charts". Cash Box Top Singles. Cashbox Magazine. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Whitburn, Joel (1998). Billboard Top 10 Charts, 1958–1997. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. p. 148. ISBN 0-89820-126-8.

- "By the Time I Get to Phoenix". Songfacts. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- "Johnny Rivers Hits". JohnnyRivers.com. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: R". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved March 12, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- "Dick Clark Interviews Johnny Rivers - American Bandstand". phim pha online. February 28, 1981. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- "Dick Clark Interviews Johnny Rivers - American Bandstand". AwardsShowNetwork. February 28, 1981. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Robert Reynolds (October 3, 2016). The Music of Johnny Rivers. Reynoldsink. pp. 63–66. ISBN 9781365429408. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Simons, Jeff (May 11, 2000). "Rivers still on road with electric guitar". Amarillo Globe News. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- Marcone, Stephen (2006). Managing Your Band: Artist Management : the Ultimate Responsibility. Wayne NJ: HiMarks. pp. 297–98. ISBN 978-0965125024. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- "The Final Tour of the Legendary Johnny Rivers". NowPlayingNashville.com. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- "Johnny Rivers Concert & Tour History | Concert Archives". www.concertarchives.org. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- "Johnny Rivers – Discography 1964–1969". JohnnyRivers.com. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- "Johnny Rivers – Discography 1970–present". JohnnyRivers.com. Retrieved October 31, 2010.