Infighting in the Gulf Cartel

The infighting in the Gulf Cartel refers to a series of confrontations between the Metros and the Rojos, two factions within Gulf Cartel that engaged in a power struggle directly after the death of the drug lord Samuel Flores Borrego in September 2011. The infighting has lasted through 2013, although the Metros have gained the advantage and regained control of the major cities controlled by the cartel when it was essentially one organization.

| Infighting in the Gulf cartel | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mexican drug war | ||||

.jpg.webp) map of territories of Los Metros (grey) and Los Rojos (purple) in 2021 | ||||

| Date | 2 September 2011 – present | |||

| Location | ||||

| Caused by | Civil confrontation between Los Rojos and Los Metros to take Reynosa, Tamaulipas, territory not granted to Los Rojos | |||

| Goals | Conquest of Reynosa, Tamaulipas | |||

| Parties | ||||

| ||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Death(s) | +200 deaths[1][2][3] | |||

Originally, the two factions were formed in the late 1990s by Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the former leader of the criminal organization. After the drug lord's arrest and extradition in 2003 and 2007 respectively, the control of the Gulf Cartel went on to his brother Antonio Cárdenas Guillén (Tony Tormenta) and close associate Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez (El Coss). But the differences between the two factions began in 2010, when Juan Mejía González of the Rojos was overlooked as the regional boss for Reynosa, Tamaulipas during a cartel shift and appointed to a less-important territory. In the assignment, Flores Borrego of the Metros was given Reynosa, suggesting that the Metros were above the Rojos. When Antonio was killed by the Mexican marines on 5 November 2010 in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, his faction – the Rojos – perceived that the Metros had tipped the Mexican authorities to Antonio's whereabouts. Those who were more loyal to the Cárdenas drug family stayed with the Rojos, while those loyal to Costilla Sánchez stayed in the Metros.

In efforts to seek revenge for the death of their leader, Mejía González and Rafael Cárdenas Vela, the nephew of Antonio, allegedly ordered the execution of Flores Borrego, the second-in-command in the Metros faction. With his death, both two factions turned their guns against each other and went to war in the Mexican northern state of Tamaulipas, and reportedly offered information to U.S. authorities on the location of cartel members hiding in the United States. In the infighting, many high-ranking members of the Gulf Cartel have been killed or arrested. In some cases, however, the drug-related violence extended across the U.S.–Mexico border in South Texas, prompting debates on the possibility of "spillover violence" from the Mexican Drug War.

The fight has forced the Rojos to barricade in Matamoros, Tamaulipas while the Metros make their final incursions to put them down. In order to do so, Costilla Sánchez of the Metros allegedly worked with the Sinaloa Cartel and Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán. Nonetheless, after the arrests of Costilla Sánchez and Cárdenas Guillén, it is difficult to predict what fate lies ahead for the Gulf Cartel and Mexico's criminal underworld.

Background

In the late 1990s, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the former leader of the Gulf Cartel, had other similar groups besides Los Zetas established in several cities in Tamaulipas.[4] Each of these groups were identified by their radio codes: the Rojos were based in Reynosa; the Metros were headquartered in Matamoros; and the Lobos were established in Laredo.[4] The infighting between the Metros and the Rojos of the Gulf Cartel began in 2010, when Juan Mejía González, nicknamed El R-1, was overlooked as the candidate of the regional boss of Reynosa and was sent to La Frontera Chica, an area that encompasses Miguel Alemán, Camargo and Ciudad Mier – directly across the U.S.–Mexico border from Starr County, Texas. The area that Mejía González wanted was given to Samuel Flores Borrego, suggesting that the Metros were above the Rojos.[4]

Unconfirmed information released by The Monitor indicated that two leaders of the Rojos, Mejía González and Rafael Cárdenas Vela, teamed up to kill Flores Borrego.[4] Cárdenas Vela had held a grudge on Flores Borrego and the Metros because he believed that they had led the Mexican military to track down and kill his uncle Antonio Cárdenas Guillén (Tony Tormenta) on 5 November 2010.[4][5] Other sources indicate that the infighting could have been caused by the suspicions that the Rojos were "too soft" on the Gulf Cartel's bitter enemy, Los Zetas.[6] When the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas split in early 2010, some members of the Rojos stayed with the Gulf Cartel, while others decided to leave and join the forces of Los Zetas.[7]

InSight Crime explains that the fundamental disagreement between the Rojos and the Metros was over leadership. Those who were more loyal to the Cárdenas family stayed with the Rojos, while those loyal to Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, like Flores Borrego, defended the Metros.[6]

Originally, the Gulf Cartel was running smoothly, but the infighting between the two factions in the Gulf Cartel triggered when Flores Borrego was killed on 2 September 2011.[4] When the Rojos turned on the Metros, the largest faction in the Gulf Cartel, firefights broke throughout Tamaulipas and drug loads were stolen among each other, but the Metros managed to retain control of the major cities that stretched from Matamoros to Miguel Alemán, Tamaulipas.[8] Two other factions in the cartel, Los Ciclones and Los Escorpiones, reportedly engaged in a power struggle on 1 February 2012 in Matamoros.[9]

'Spillover' violence

- McAllen, Texas shooting

On 27 September 2011 at around 2 a.m. in McAllen, Texas, fatal gunshots were exchanged from one vehicle to another along an expressway.[10] A man named Jorge Zavala and a 22-year-old man were victims of an attack perpetrated by unknown shooters traveling in a dark-colored SUV from a Chevrolet Tahoe, causing them to lose control of the vehicle and crash along the expressway.[10] The local police did not find a motive for the attack, but sources told The Monitor that Zavala had ties with a faction of the Gulf Cartel in the Mexican border cities of Matamoros and Reynosa, showing signs that his assassination was due to an "internal power struggle" in the organization.[10] Zavala died instantly at the scene, while the other man was taken to the hospital in critical condition. The McAllen Police Department refused to comment on how many gunshots were fired, but the preliminary autopsy revealed that Zavala died of multiple gunshots, not from the crash.[10] Public records prove that Zavala's criminal history dates back to 1995, while sources familiar with the victim stated that he was a close associate of the drug lord Gregorio Sauceda-Gamboa.[10] A local law enforcement official who asked not to be identified stated that Samuel Flores Borrego's death and the power struggle in the organization may explain Zavala's death. Hours after Zavala's death, a series of grenade attacks prompted in Reynosa, Río Bravo, and Ciudad Victoria, while an intense gunfight took place in Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[10][11]

- Sheriff shot in Elsa, Texas

After Samuel Flores Borrego was killed, the Gulf Cartel had lost many of its drug loads to rival groups and its own members, so when the new leader was appointed, "one of the first directives issued was to recuperate its losses."[12]

It is unclear how, but several Gulf Cartel members traced one of their stolen loads to a stash house of suspected dealers in Elsa, Texas on 1 November 2011. The cartel then called on an American-based prison gang to go and buy the loads to learn the location of the stash house.[12] The gang dealers then went and bought the drugs from the dealers, but realized that it was not at the stash house were the goods were allegedly hidden. In an attempt to disclose the information to the dealers, the gang members kidnapped them, and that was when two country sheriffs received an emergency call a possible kidnapping.[12] The policemen then spotted the gang member's Ford F-150 pickup truck and ordered the drivers to stop.[13] While one of the policemen was speaking to the driver, the other approached the passenger window and was shot with a 9 mm gun.[13] The policeman managed to survive because he was wearing a bullet vest. One of the gang members, however, was killed; the other was shot in the head and remained in critical condition.[13][14]

- Kidnappings and extortions in South Texas

On Memorial Day weekend in 2011, an alleged member of the Gulf Cartel pretended to be a policeman (he was in full uniform, with a pistol, handcuffs, and an embroidered shirt) and abducted a man named Ovidio Guerrero Olivares near Alton, Texas.[15] Guerrero has not been seen by his family members and court records indicate that he "wasn’t even the target of a Gulf Cartel-ordered kidnapping."[15] The police learned more about the kidnapping when they arrested a some cartel members in Mission, Texas; one of the detainees admitted that Guerrero Olivares was kidnapped after the cartel boss in Miguel Alemán, Tamaulipas issued a list of several people he wanted to be kidnapped in the Rio Grande Valley and sent south into Mexico for questioning after a load of cocaine was stolen.[15] The kidnapper was sentenced to prison, while reports from within the organization state that the cartel boss of Miguel Alemán – Miguel El Gringo Villarreal – was killed in Valle Hermoso, Tamaulipas during the cartel infighting.[15] In addition, the family of Guerrero Olivares fled and abandoned their house.[15]

On 6 December 2011, a high-speed chase and an attempted vehicle aggression by alleged cartel members on police officers in Palmview, Texas prompted a nine-shot confrontation.[16] Isaac Sánchez Gutiérrez, the driver of the vehicle, managed to escape the scene and avoid capture, leaving behind a partner and a Ford F-150 pick-up truck the letters "CDG" – the Spanish acronym for the Gulf Cartel – spray-painted in the inside. The authorities later discovered more than 700 pounds of cannabis hidden inside the truck.[16] Sánchez Gutiérrez was arrested by the U.S. Border Patrol agency after a vehicle-and-foot chase incident near Abram, Texas on 20 December 2011. While in custody, he claimed that a high-ranking leader of the cartel in Reynosa, Tamaulipas had coerced him to smuggle drugs across the border.[16] According to his account, his brother Juan Armando had been involved in the drug business but was suspected by his Reynosa superiors of stealing US$2 million. Juan Armando was kidnapped at a convenience store in Reynosa, and several cartel members went to Isaac's home in Mission, Texas threatening to torture and kill his brother if the money was not returned. They issued him an ultimatum: Either gather US$4 million, or smuggle 50 drug across the U.S.–Mexico border into Texas to free his kidnapped brother.[16][17]

Reactions

The debates over whether the violence in the McAllen metropolitan area should be considered an actual "spillover" from Mexico's drug war reignited when a sheriff from Hidalgo County, Texas was wounded in a shooting on 1 November 2011 with members of the Gulf Cartel.[18] On one side, local and federal U.S. law enforcement agents claim that the drug-related violence coming from Mexico stops at the border. The other side, made up mainly from politicians, claim that the border regions are being "overrun by drug cartels."[18] The debate relies on exactly how both sides define a "spillover" occurrence. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines a spillover incident as any crime that occurs in the United States that is directly tied with the violent conflicts in Mexico, either between law enforcement officials and drug traffickers, or between rival drug trafficking organizations.[18] The Texas Department of Public Safety, however, defines a spillover as any drug-related violence. By the DPS standards, a conflict over a drug deal between the Sicilian Mafia and the Chinese triads in New York City can fall under the spillover category.[18] Hence, the local authorities in South Texas have concluded that although violence does occur in their region, it is not directly related to Mexico but to individuals in the United States.[18]

According to the sheriff, after the death of Flores Borrego in September 2011, a gang in the United States were given orders by their Mexican superiors to recover a drug load that had been taken from the Gulf Cartel.[18][19] The process did not go as planned and the gang members ended up kidnapping a group of dealers, leading to a shootout incident. The sheriff said that this "represents the only direct spillover" case of Mexico's drug war in South Texas, but stated that it was not directly related to Mexico.[18] After this incident, Todd Staples, a Republican party Commissioner of the Texas Department of Agriculture, set up a website asking the federal government to back state efforts to curb illegal activities along the Mexican border, and especially drug trafficking.[20] In a report, Staples asked two decorated military generals to take on the assignment, and stated in September 2011 that "living and conducting business in a Texas border county is tantamount to living in a war zone."[20] Staples announced that Mexican drug cartels are seeking to create their own turf in the United States, but especially on the South Texas, which they consider "vulnerable."[21] The statement sparked criticism among local officials who argued that many of the Texan border cities have lower crime rates than cities like Houston, that are not along the border.[20] Henry Cuellar, a Democratic party member and a U.S. Representative, strongly disagreed with Staples' assessment that the Texas border is a war zone or an area overrun by the Mexican criminal groups, and claimed that such claims simply create "confusion" and unnecessary alarmist reactions.[22] On early November 2011, Greg Abbott, the Texas Attorney General, informed media outlets of a letter he sent to President Barack Obama on his failure to protect the border, and warned him that the drug violence from Mexico is increasingly "spilling over" the border, and urged Obama to "immediately dedicate more manpower to border security."[23] In the letter, Abbott wrote about the shootings and kidnappings that have been occurring in the Rio Grande Valley, and how these incidents are a "threat to national security."[24]

Lupe Treviño, the sheriff that was wounded, disagreed with Abbott's statements in a meeting at the White House with several Department of Homeland Security agencies and Janet Napolitano, and claimed that he has implemented a four-step program designed to have all of his deputies undergo a special tactical training designed to apply SWAT-style techniques to tackle any violence along the border.[25] He explicitly said that the "[U.S] border is not in chaos," and that the claims by the Republicans were "untrue and unfairly painted."[26] Nevertheless, Carlos Cascos, the current Cameron County judge, questioned Treviño's comments through Facebook, and mentioned that if South Texas didn't have drug violence issues (as Treviño claimed in Washington), then Treviño's travel to Washington D.C. was completely unnecessary, which indicates that the sheriff's actions contradicted his statements.[27]

The claims that South Texas is a "war zone" and overrun by the drug trafficking organizations are not based on current crime statistics.[22] According to the FBI Uniform Crime Reports, the number of homicides in Hidalgo County, Texas in 2010 were considerably less than in other major cities across Texas. That year, 36 homicides were reported, while "Houston reported 269 homicides, Dallas reported 148, San Antonio reported 79, and Austin reported 38."[22]

.jpg.webp)

Arrests and killings

Dávila García's killing

On 11 October 2011, the struggle between the Metros and the Rojos intensified when the Mexican authorities found the body of César Dávila García inside an abandoned house in Reynosa, Tamaulipas.[28] Inside the abandoned house, the corpse of El Comandante Gama, Dávila García's code name, had been shot with a 9 mm pistol. According to the Mexican authorities, the man was a top financial operator in the Gulf Cartel and a close associate of the former drug lord Antonio Cárdenas Guillén. After the drug lord's death, Dávila García became the regional drug baron of the coastal city of Tampico, Tamaulipas before moving back to Matamoros.[28] Neither faction in the Gulf Cartel claimed responsibility for his death, but Mexican intelligence sources indicated that Dávila García was killed by the Metros.[6] The assassination also happened a day after the Mexican Navy dismantled a network of the Gulf Cartel in three municipalities across Tamaulipas, where 35 cartel members were arrested.[29] Ricardo Salazar Pequeño, the regional boss of the cartel in Ciudad Miguel Alemán, along with the cartel's accountant Gabriela Gómez Robles, were apprehended. In addition, several firearms, drug loads, and radio communication equipment were confiscated.[30]

Matamoros prison massacre

On 15 October 2011 in the border city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, a large-scale prison riot left 20 inmates dead and 12 others wounded.[31] The brawl broke out between two inmates at around 8:00 a.m. but later extended to the rest of the prison.[32] In the turmoil, the Mexican federal police and the Tamaulipas state police were summoned to help the guards regain control of the prison. The Mexican military later took control of the prison at around 10:30 a.m.[32] News videos showed helicopters in the air over the watchtower.[33] Later in the morning, the family members gathered outside the prison to await the news of their loved ones while Mexican authorities set up a booth to take care of their requests and inquires.[34]

According to The Monitor, sources confirmed that the prison brawl was related to the fight between the Metros and the Rojos.[35]

Cárdenas Vela's arrest

On 20 October 2011, while heading to his luxury house in South Padre Island, Texas with his bodyguards and a lady,[36] Rafael Cárdenas Vela, a drug lord of the Gulf Cartel and a leader of the Rojos, was pulled over and arrested in Port Isabel, Texas by the police who were reportedly working with federal agents that had been tipped to his whereabouts.[37] Stratfor and the San Antonio Express-News released a report on 3 November 2011 putting more context on the arrest of Cárdenas Vela in South Texas and stated that the Metros had probably played a role in his arrest.[38]

"Cartels usually try to avoid conducting hits on U.S. soil, which may explain why Costilla Sanchez's faction may have tipped off U.S. authorities instead of killing him. There has not been any confirmation that Los Metros was responsible for the tip to U.S. authorities, but even if it was not, it will benefit from the hit taken by its intra-cartel rivals with the loss of their leader."[38]

— Stratfor

The Monitor reported on 27 October 2011 that a rescue attempt for Cárdenas Vela was very unlikely. Despite being a powerful leader in the Gulf Cartel, his rude actions "burned many bridges in the organization."[39] A source outside law enforcement but with direct knowledge of the situation stated that Cárdenas Vela was "very hardheaded and impulsive," which made him have many enemies in the organization. "(Some of the) comandantes are glad he is gone," the source said.[39] Moreover, Cárdenas Vela's arrest triggered a series of road blocks and gunfights in Valle Hermoso and Matamoros, Tamaulipas, the city in which he operated. By 27 October 2011, El Universal reported a total of 14 killings as a result of his arrest and of the Gulf Cartel infighting.[40]

Ramos García's arrest

U.S. Border Patrol agents arrested Eudoxio Ramos-García, a former drug lord of the Gulf Cartel, in Rio Grande City, Texas on 31 October 2011.[41]

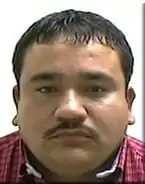

Zúñiga Hernández's arrest

On 1 November 2011 in the city of Santa Maria, Texas, José Luis Zúñiga Hernández (Comandante Wicho), a high-ranking member of the Gulf Cartel, was arrested in Santa Maria, Texas on 26 October 2011 by U.S. Border Patrol agents.[42] During his arrest, Zúñiga was carrying cocaine, $20,000 US dollars in cash, and a gold, diamond, and ruby encrusted .38 Super Colt handgun.[43][44] The pistol has the name "Wicho" encrusted on it.[45] He also "freely admitted" to be a Mexican national without documents to reside in the United States, while sources familiar with Zúñiga Hernández indicate that he turned himself in to American authorities.[46] His attorney testified that ICE agents coerced Zúñiga Hernández to confess his crimes and cooperate with them in exchange for protection to his family and immunity from prosecution. The ICE agents denied such claims, however.[47]

Zúñiga Hernández was the cartel boss in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas after the death of Antonio Cárdenas Guillén (a.k.a. Tony Tormenta) on 5 November 2010.[42] Nonetheless, according to court documents, he was ousted as the regional boss by Rafael Cárdenas Vela on 10 March 2011 after the internal feud in the Gulf Cartel, and fled to the United States illegally under death threats.[48] He pleaded guilty to in January 2012 to firearm charges and illegal entry after being deported from the United States on 8 August 1997.[48] Prior to his deportation, Zúñiga Hernández was found guilty on 14 February 1990 for marijuana distribution.[43] He currently faces up to 20 years in prison after entering the U.S. illegally after deportation, and an additional 10 years for being an alien with a firearm. Each of these two convictions carries a fine of $250,000 U.S. dollars.[43]

On 24 January 2013, Zúñiga Hernández was sentenced to seven years in prison in Brownsville, Texas, after pleading guilty for illegal possession of firearms and for entering the United States unauthorized.[49]

Cárdenas Guillén's arrest

Mario Cárdenas Guillén, wearing a black bullet-proof vest and flanked by two ski-masked marines, was presented on national television on 4 September 2012.[50] According to reports issued by the Mexican Navy, Cárdenas Guillén was arrested a day before in the city of Altamira, Tamaulipas.[51] At the time of his arrest, Cárdenas Guillén was carrying a rifle in front of a building entrance, along with $10,000 in cash, radiocommunication equipment, ammunition, several credit cards, and four envelopes containing cocaine.[52] The arrest of Mario is one of the "highest-profile arrests in months" and a powerful blow to the Gulf Cartel, which lost much of its influence after it separated from Los Zetas in early 2010.[50]

Costilla Sánchez's arrest

The Mexican Navy arrested Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, the supreme leader of the Gulf Cartel, on 12 September 2012 in the residential Lomas de Rosales neighborhood in Tampico, Tamaulipas without firing a single bullet.[53]

He was presented on camera in the morning of 13 September 2012, handcuffed and wearing a long-sleeve shirt. Ten bodyguards of Costilla Sánchez were also arrested during the operative.[54] Ernesto Banda Chaires, one of the detainees, is believed to be the regional boss of the cartel in Tampico.[55] In the Wednesday arrest, the Mexican authorities confiscated several assault rifles, pistols encrusted with jewelry, and a number of expensive-looking watches. When asked if he had anything to say about his criminal charges and if he had a lawyer, Costilla Sánchez shook his head.[56]

Present-day

By December 2011, media reports indicated that Mario Cárdenas Guillén, the brother of the late Antonio Cárdenas Guillén and of the imprisoned Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, had assumed control of the Gulf Cartel.[57] Nonetheless, Mario was not very active in his family affairs and his reluctance to get directly involved in the cartel's drug operations appears to have continued after the death of Antonio.[57] The Mexican Navy, however, arrested him on 3 September 2012 in the city of Altamira, Tamaulipas.[58] In addition, the current leader of the organization, Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, had been reclusive and never had a permanent spot, often retreating to one of his ranches where he gives orders.[57] Costilla Sánchez never got involved in the day-by-day operations of the cartel, but it seemed unlikely that he will be replaced, given Mario's arrest and past behavior.[57]

In early 2012, the infighting between the Rojos and the Metros that left bloody confrontations and high-ranking arrests has diminished.[59] Nonetheless, the Gulf Cartel had to change its logistics and reconstruct how it manages regional bosses, while other sources say that the Rojos are no longer part of the cartel.[60] In the end, the control fell to the cartel members of the Metros faction, although the Rojos still has significant manpower.[59] The Rojos and the forces loyal to the Cardenas drug family have barricaded in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, while their leader Juan Mejía González has fallen off the radar and has not been heard off since then.[61] A day after several members of the Metros put up banners commemorating the late Samuel Flores Borrego on 6 August 2012, gunfighting occurred in the city, and the Metros' push in Matamoros is a sign that they are determined to remove people who turned against the organization in the past.[61]

However, while the Metros have gained the upper hand in the operations of the cartel, the infighting left them vulnerable to attacks.[57] To be sure, any drug trafficking organization is vulnerable to attacks when infightings occur, but the Gulf Cartel's feud with Los Zetas will compound the problem and make the infighting even more volatile.[57][62] The infighting and struggle between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas has surely weakened both organizations, but Los Zetas continue to control key territories in Tamaulipas and seems to have the advantage of recruiting seemingly limitless gunmen from South America, while the Gulf Cartel is opting for young, less-experienced recruits from its territories.[4][62] Moreover, the cartel infighting can open doors for Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán of the Sinaloa Cartel to send gunmen to Tamaulipas.[63] The current alliance between the Sinaloa cartel and the Gulf Cartel is only a "marriage of convenience;" the ultimate goal of El Chapo Guzmán is to take over Tamaulipas, and working with Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez was his only access. Costilla Sánchez, on the other hand, needed the Sinaloa cartel's support to fight off Los Zetas and settle disputes with the Rojos.[61]

Costilla Sánchez's and Cárdenas Guillén's arrests

The capture of Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez and Mario Cárdenas Guillén leaves the Gulf Cartel without a definite successor. Both arrests in effect wipe out the traditional old-time bosses of the cartel, putting an end to a generation of drug traffickers.[64][65] When Cárdenas Guillén was arrested on 4 September 2012, it looked as if Costilla Sánchez had finally won the leadership of the Gulf Cartel. Throughout the end of 2011 and until the time of his arrest in 2012, Costilla Sánchez had carried out a campaign to put down Cárdenas Guillén and his faction – the Rojos – by reportedly setting up its members to get arrested or killed. His attempts to successfully put down his rivals allegedly gave him the protection of some high-ranking officials in the Mexican Armed Forces.[64]

Nonetheless, Costilla Sánchez's own tactics backfired after a group of his henchmen arrested in Río Bravo, Tamaulipas reportedly betrayed him and notified the authorities of his whereabouts. It is also possible Cárdenas Guillén's declarations resulted in the apprehension of Costilla Sánchez too.[64]

Without a clear successor of Costilla Sánchez, his faction – the Metros – could come to an end, although it is still likely that there are other old-crime boses of lesser importance still trying to keep the Gulf Cartel standing.[64] With the recent arrest of a Gulf Cartel representative in Colombia, the drug business could be disrupted even further. One clear benefactor of the fall of the Gulf Cartel is its rival group, Los Zetas. It is also possible that the several within the Gulf Cartel may decide to join the Sinaloa Cartel or Los Zetas, although the latter seems unlikely given the bitter sentiment both groups have planted.[64]

Currently, Los Zetas is also experiencing a power struggle within its own ranks, so the future of the Gulf Cartel is difficult to predict.[64]

Metro 4's assassination

El Metro 4, a high-ranking lieutenant of the Gulf Cartel, was reportedly killed by Los Zetas or by members of his own cartel on January 15, 2013.[66]

See also

References

- "UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program". ucdp.uu.se. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- "UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program". ucdp.uu.se. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- "UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program". ucdp.uu.se. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- "Internal struggle in the Gulf Cartel could weaken the organization". The Monitor. 29 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Major Arrests Expected to Shake Up Gulf Cartel". KRGV-TV. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Pachico, Elyssa (11 October 2011). "Death of Gulf Cartel 'Finance Chief' Sign of Internal Strife?". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Mexico: Gulf Cartel lieutenant, his right-hand man captured". The Monitor. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Gulf Cartel lieutenant linked to various incidents on U.S side of border". The Monitor. 2 January 2012. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Tiroteo en Matamoros". KNVO 48 (in Spanish). 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Sources: Fatal gunshots on McAllen expressway point to Gulf Cartel". The Monitor. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Probe of possible Gulf Cartel hit in McAllen continues". The Monitor. 29 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Lopez, Naxiely (1 November 2011). "Deputy shooting apparently linked to Gulf Cartel". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Sheriff: Police shooting marks 1st bona fide 'spillover' violence in Hidalgo County". The Monitor. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Moore, Gary (29 November 2011). "Mexican Spillover Violence: The Riddles Grow". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Taylor, Jared (23 January 2012). "Gulf Cartel launched kidnapping ring in Rio Grande Valley last year". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Gulf Cartel lieutenant linked to various incidents in the U.S side". The Brownsville Herald. 2 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Taylor, Jared (21 December 2011). "Palmview chase suspect: Gulf Cartel forced me to smuggle". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Politicians, law enforcement clash over spillover violence". The Monitor. 18 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Lopez, Naxiely (1 November 2011). "Sheriff: Police shooting marks 1st bona fide 'spillover' violence in Hidalgo County". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Lopez, Naxiely (26 October 2011). "VIDEO: State ag commish leads border talks at Crime Stopper conference". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Todd Staples (25 September 2011). "Staples: Texans want action on border security". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Ortiz, Ildefonso (17 November 2011). "Politicians, law enforcement clash over violence spillover from Mexico". Valley Freedom. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (2 November 2011). "Texan warns Obama: Mexican cartels 'spilling over' border". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Texas AG asks Obama to take action on border security, claims drug cartel violence threatens US". El Paso Times. 3 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Martin, Gary (17 November 2011). "South Texas lawmen strongly dispute GOP's border "war zone" claims". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Martin, Gary (16 November 2011). "Border sheriffs refute GOP claims of border war zone". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Ortiz, Ildefonso (17 November 2011). "Trickle or Flood? Groups clash over true extent of violence spillover from Mexico". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Gulf Cartel lieutenant's death linked to infighting". The Brownsville Herald. 13 October 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Tamaulipas: marinos hallan muerto a presunto contador del cártel del Golfo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Estrada, Javier (10 October 2011). "La Marina desarticula red del cártel del Golfo en Tamaulipas". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Chapa, Sergio (15 October 2011). "20 inmates killed, 12 wounded in Matamoros prison brawl". Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Twenty die in Mexican prison fight near US border". The Guardian. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Wilkinson, Tracy (16 October 2011). "Mexico prison riot leaves at least 20 dead". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Matamoros prison fight leaves 20 inmates dead". Valley Morning Star. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Struggle within cartel looks to weaken organization". The Monitor. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "'Heir' to Gulf Cartel arrested in Port Isabel". The Brownsville Herald. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Schiller, Dane (26 October 2011). "Nephew of Mexican cartel kingpin busted in Texas". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Some context on Gulf Cartel arrests in Texas". San Antonio Express-News. 3 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Impact questioned after capture of Gulf Cartel 'heir'". The Monitor. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Catorce muertos, tras el arresto". El Universal (in Spanish). 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Chapa, Sergio (31 October 2011). "Former Gulf Cartel leader arrested in Rio Grande City". KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- O'Reilly, Andrew (1 November 2011). "US Authorities Arrest Boss Of Mexico's Gulf Cartel". Fox News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Guilty Plea on Eve of Jury Selection for Zuniga-Hernandez". United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Brezosky, Lynn (18 June 2012). "Gulf Cartel figure withdraws guilty pleas". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Buckley, Madeline (19 June 2012). "Man admits holding Wicho's gold, jewel-encrusted gun". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Top Gulf Cartel boss detained by U.S. authorities". The Monitor. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Buckley, Madeline (23 December 2011). "Zúñiga evidence gathered so far is all admissible". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Buckley, Madeline (12 March 2012). "Matamoros plaza boss pleads to drug trafficking". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Gulf Cartel boss 'El Wicho' gets 7 years in prison". The Monitor (Texas). 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Jackson, Allison (4 September 2012). "Mexico: Gulf Cartel leader Mario Cardenas Guillen, or 'The Fat One,' arrested". GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Otero, Silvia (4 September 2012). "Presenta Marina a hermano de Osiel Cárdenas". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "Presenta Marina a hermano de Osiel Cárdenas". Yahoo! News (in Spanish). 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "Gulf Cartel supreme leader 'El Coss' reported captured in Tampico". KVEO-TV. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Castillo, Mariano (13 September 2012). "Mexico says Gulf Cartel boss arrested". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "La Marina presenta al presunto líder del cártel del Golfo, 'El Coss'". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "Mexico catches purported leader of influential drug cartel". Fox News. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- (subscription required) "Polarization and Sustained Violence in Mexico's Cartel War". Stratfor. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Castillo, Gustavo (4 September 2012). "Detiene Marina a Mario Cárdenas Guillén, líder del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "Reynosa rooster honors slain Gulf Cartel boss, Sinaloa alliance". The Monitor. 21 January 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Tiroteos en Tamaulipas tras la captura de El Junior, sobrino de Osiel Cárdenas". La Jornada (in Spanish). 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Officials: Gulf Cartel rift points to renewed violence". The Monitor. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Ortiz, Ildelfonso (25 August 2012). "Amid regular firefights, Mexican border cities under siege". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Drug War Exiles: Amid Gulf Cartel infighting, leaders taken in by U.S. authorities". The Monitor. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Stone, Hannah (13 September 2012). "Capture of Gulf Boss Leaves Zetas Split in Spotlight". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Wilkinson, Tracy (13 September 2012). "Suspected top Gulf cartel leader captured in Mexico". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Fox, Edward (17 January 2013). "'Gulf Cartel Leader Assassinated in Northern Mexico'". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

External links

- (in Spanish) Golfo y Costilla: Q&A (archived) — Animal Político

- Polarization and Sustained Violence in Mexico's Cartel War (archived) — Beckley Foundation

- Texas gangs have evolving relationship with cartels — (archived) — San Antonio Express-News

- Mexico's government begins to retake Northeastern Mexico (archived) — Gary J. Hale, James Baker Institute