Jotunheimen

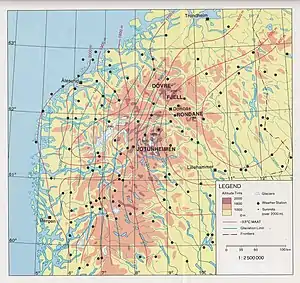

Jotunheimen (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈjôːtʉnˌhæɪmn̩]; "the home of the Jötunn") is a mountainous area of roughly 3,500 square kilometres (1,400 sq mi)[3] in southern Norway and is part of the long range known as the Scandinavian Mountains. The 29 highest mountains in Norway are all located in the Jotunheimen mountains, including the 2,469-metre (8,100 ft) tall mountain Galdhøpiggen (the highest point in Norway and Northern Europe). The Jotunheimen mountains straddle the border between Innlandet and Vestland counties (historically part of the old Oppland and Sogn og Fjordane counties).[3]

| Jotunheimen | |

|---|---|

View from Galdhøpiggen | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Galdhøpiggen, Lom Municipality |

| Elevation | 2,469 m (8,100 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 2,436 m (7,992 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 61.63644°N 8.31248°E |

| Geography | |

Location of the mountain  Jotunheimen (Vestland)  Jotunheimen (Norway) | |

| Location | Innlandet, Norway |

| Range coordinates | 61°36′18″N 8°28′39″E[2] |

| Parent range | Scandinavian Mountains |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Caledonian orogeny |

Hiking, mountaineering and skiing

Jotunheimen is very popular with hikers and climbers, and the Norwegian Mountain Touring Association maintains a number of mountain lodges in the area, as well as marked trails that run between the lodges and others that run up to some of the peaks. The area has more than 50 marked trails, ranging from shorter hikes to multi day trails.[4]

Mountaineering in Jotunheimen was pioneered in the late 19th century and early 20th century by British mountaineers William Cecil Slingsby, Harold Raeburn, and Howard Priestman as well as Norwegian mountaineers such as Kristian Tandberg, George Paus and Therese Bertheau. Slingsby's 1904 book Norway, the Northern Playground contributed greatly to popularizing mountaineering in Jotunheimen among the international mountaineering community.

The image from Gjende shows a cliff trailing down into the lake. At its base there is a popular guest house called Memurubu. The picture is taken from Gjendesheim, a starting point for hiking into the mountain range. There is a very popular trail along Besseggen that follows the edge of the mountainous range to the right, which it is named after.

There is a National Tourist Route, the Sognefjell Road, from Skjolden to Lom and another road, the RV 51, from Gol to Vågå through the special area of Valdresflya.

Etymology

Originally there was no common name for this large mountainous area. However, in 1820, the Norwegian geologist and mountaineer, Baltazar Mathias Keilhau proposed the name Jotunfjeldene "the mountains of the Jotnar" (inspired by the German name Riesengebirge). This was later changed to Jotunheimen by the poet Aasmund Olavsson Vinje in 1862 – this name/form was directly inspired by the name Jötunheimr in Norse mythology.

Geology

Jotunheimen is a residual mountain area, which is a mass of rock that has remained in place as the surrounding relief has been eroded. The tops of Dovrefjell and Jotunheimen and other parts of southern Norway are the few remnants of a formerly flat surface that existed in Norway prior to uplift. This surface is now largely eroded and warped. The said erosion formed a series of steps and it is from the highest of these steps that Jotunheimen rise.[5]

Geomorphology

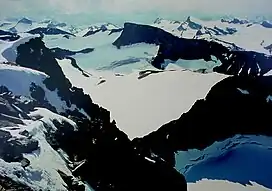

The characteristic mountain landforms in Jotunheimen have been sculptured by glacial geomorphology during the Pleistocene, especially during its last glacial period. Whereas the Scandinavian Ice Sheet covered most of Fennoscandia, some mountain peaks of Jotunheimen were not covered by glaciers and remained as Nunatak. Galdhopiggen, Glittertinden or Store Lauvhøi are examples. Towards the west, the Scandinavian Ice Sheet disintegrated in several glacier tongues and caused the formation of the Norwegian Fiords.

Climate, glaciers and permafrost

Jotunheimen lays in the transition zone from a maritime climate in the west and a more continental climate towards the east. The high mean annual precipitation in the west leads to a low glaciation limit of less than 1500 meters, the altitude where glaciers can be formed. In the east of Jotunheimen, glaciers are rare and the glaciation limit rises to an altitude of more than 2100 meters. The opposite trend may be registered for the mean annual air temperatures (MAAT). It drops about 600 meters for any given value of a MAAT, The MAAT of -3.5 °C indicates areas with occurrences of widespread mountain permafrost. Thus, permafrost existis in large parts of Jotunheimen due its more continental climate.[6]

Since the 1980s, the Jotunheimen area has got increased scientific interest from geologists and geomorphologists due to its climate creating periglacial landforms and widespread and often thick permafrost occurrences. A first comprehensive study on mountain permafrost in Scandinavia was published in 1982.[7] Today, these findings are confirmed at various places, and Juvvasshøi, Juvasshytta and Galdhøi are preferred areas for scientific periglacial research due to yearround good logistic conditions compared with arctic areas.[8]

Jotunheimen National Park

Jotunheimen contains Jotunheimen National Park, which was established in 1980 and covers an area of 1,151 square kilometres (444 sq mi).[9] The Hurrungane mountain range is also inside the national park with the sharpest peaks in Jotunheimen. Adjacent to the national park border is Utladalen Nature Reserve which covers the Utladalen valley and the mountain Falketind, amongst others.

According to the anthropologist Shoshi Parks, “Three national parks converge in this region of Norway, but Jotunheimen is by far the most spectacular, with 250 peaks over 1,900 metres (6,200 ft) high, including two of the highest in northern Europe – (Galdhøpiggen and Glittertind),”[10]

Human presence

The Jotunheimen shoe was discovered in August 2006. Archaeologists estimate that the leather shoe was made between 1800 and 1100 BC,[11] making it the oldest article of clothing discovered in Scandinavia. It was discovered along with several arrows and a wooden spade, leading archaeologists to conclude that they had unearthed an important hunting ground.

In February 2020, Secrets of the Ice Program researchers discovered a 1,500-year-old Viking arrowhead dating back to the Germanic Iron Age and locked in a glacier in southern Norway caused by the climate change in the Jotunheimen Mountains. The arrowhead made of iron was revealed with its cracked wooden shaft and a feather, is 17 centimetres (6.7 in) long and weighs just 28 grams (1.0 oz).[12][13][10]

Traffic

Despite the large area of Jotunheimen, there are few roads for car traffic. Between Jotunheimen and Breheimen, the plateau is crossed by the Norwegian County Road 55. To the west, the road continues further from Skjolden via Sogndalsfjøra, Balestrand and Høyanger to the European route E39. In the east, the road leads to Lom. A few small dirt roads lead to different parts of the edge of Jotunheimen National Park, although the area of the national park itself is practically roadless. A small exception, however, is a blind road in the Veodalen to Glitterheim, whose head is inside the national park area near the Glittertind.

See also

References

- "Galdhøpiggen". PeakVisor.com. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- "Jotunheimen, Luster" (in Norwegian). yr.no. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- Thorsnæs, Geir, ed. (2021-05-19). "Jotunheimen". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- "Jotunheimen National Park Travel Guide (Hiking Tips + Trails) - The Norway Guide". thenorwayguide.com. 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna; Ollier, C.D.; Sulebak, J.R. (2000). "Landforms and uplift history of southern Norway". Global and Planetary Change. 24 (3–4): 211–231. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00009-6.

- King, Lorenz (1983). "High Mountain Permafrost in Scandinavia". Permafrost: Fourth International Conference, Proceedings: 612–617.

- King, Lorenz (1984). "Permafrost in Skandinavien - Untersuchungsergebnisse aus Lappland, Jotunheimen und Dovre/Rondane". Heidelberger Geographische Arbeiten (in German). 76: 174 pages.

- Harris, Charles; Haeberli, Wilfried; Vonder Mühll, Daniel; King, Lorenz (2001). "Permafrost Monitoring in the High Mountains of Europe: the PACE Project in its Global Context". Permafrost and Periglacial Processes. 12 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1002/ppp.377.

- http://www.dirnat.no/attachment.ap?id=7074%5B%5D

- "1,500-Year-Old Viking Arrowhead Found After Glacier Melts in Norway". Curiosmos. 2020-03-09. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- Bailey, Stephanie. "Climate change reveals, and threatens, thawing relics". CNN. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- Ramming, Audrey (2020-03-06). "Photo Friday: Norwegian Glacial Ice Preserves Ancient Viking Artifacts". GlacierHub. Retrieved 2020-03-25.