Jublains archeological site

The Jublains archeological site is a cluster of ruins, mostly dating back to Ancient Rome, in the current French commune of Jublains in the département of Mayenne in the Pays de la Loire.

| |

| Location | Mayenne, France |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 48.2591°N 0.4978°W |

| |

| Region | Pays de la Loire |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Periods | Roman Empire Merovingian |

| Cultures | La Tène culture Diablintes |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | René Rebuffat, François-Jean Verger, Augustin Magdelaine, Henri Barbe, Robert Boissel and René Diehl |

| Ownership | Mayenne |

Roman imperial authorities built a city named Noviodunum on the site of a temple of the Celtic Diablintes, which became the capital of this people in the Augustinian administrative reorganization.[1] Settled in the second half of the 1st century, its public buildings testify to the spread of the Roman way of life: theatre, forum and baths, in addition to the Celtic temple, which was rebuilt in stone. The difficulties the city experienced beginning in the 3rd century can be read in the fortifications built in that period, which are still the most impressive features of the site. In late antiquity the settlement lost its status as a capital when the Diablintes were absorbed into the Cenomani culture.

Jublains is mostly known for its "Roman camp", registered as a monument historique in 1840.[2] Even though a simple bourg replaced the Roman city, the remarkably well-preserved ruins make Jublains an exceptional site. The département of Mayenne decided to acquire several parcels of real estate, to allow research on the early residents of the commune.

History

Celtic site

Jublains has been inhabited since at least the La Tène culture in the Iron Age, although the archaeological record confirms that it was hardly urban at that time. The site isn't far from the Oppidum of Moulay, which has a 135-hectare enclosure with double ramparts. A votive collection of swords from the period was discovered in a 19th-century excavation of the temple, and another at the end of the 1970s discovered Armorican-type pottery with fingerprint motifs. A monolith was also discovered when the village church was rebuilt in 1877, which may date from the Iron Age. Another stone was unearthed in the cavea of the theatre. A Gaulish enclosure came to light in the excavations of the 1970s, containing materials believed to have been related to coin manufacturing. Gold staters were also discovered.[3]

Gallo-Roman settlement

The presence of a village built at the foot of a wooden temple, no doubt a Diablintes temple, likely explains the decision in the Roman era to erect a fortress there.[4][3] The city named Noviodunum (Gaulish: "new fortress") was the most important Diablintes settlement and was mentioned by Ptolemy[5] and included in the Tabula Peutingeriana, where it was erroneously labelled Nu dionnum, on the same road as Araegenue.[6][7] It was an important crossroads, with links to some ten other settlements.[8] Urbanisation of the site began around the year 20, but in a disorganized manner.[4] The influence of the Roman Empire increased in the middle of the 1st century, as attested by the coins found at or near the site.[3]

The temple was rebuilt in stone at some point after 65, and public monuments were erected, and contributed to the Romanisation of the local population. In the second half of the first century, Noviodunum was given a grid plan.[4] However, the intended urban planning was largely moot, as the city never occupied the planned grid, and therefore part of the site never became urbanised.[9] However, the north-west to south-east axis of the public buildings reflects the orientation and footprint that were originally intended. At the end of the second century or perhaps in the early 3rd century, construction began on the most famous of the Roman ruins there, the castellum, considered the best-preserved Roman fortification in France. The site was initially described as military, but in the 1970s, the work of René Rebuffat highlighted its role as a relay station linked to the cura annonae, a function enabled by Noviodunum's favorable road access.[10] Also according to Rebuffat, construction of the outer wall was begun in the reign of Diocletian, but it was never finished because of the fortress' decline in strategic importance.[10]

Gradual decline

The settlement had declined sharply by the 4th century;[11] the coins and imported ceramics found at the site date no later than the reign of Constantine or Magnentius.[9][10] Noviodunum was by then distant from the roads toward the Germanic limes,[12] and more importantly faced competition from growing cities like Le Mans.

At the end of the 4th century or the beginning of the 5th the Diablintes were absorbed by the Aulerques Cénomans, and the site became a simple vicus.[9] The location continued to be inhabited even though it was Vindunum, the capital of the Cénomans, (which became Le Mans) that was the metropolis and the seat of the Episcopal see.[10] The decline was very gradual.[9] In this period the baths were converted into a church, and dwellings emerged in the Merovingian era on the ruins of a Roman villa and even on those of the theatre.[12] In the 6th and 7th centuries, the site remained the location of a military relay against the Bretons.[13]

The area was depopulated in the 10th century. The ruins of the castellum were reused in the construction of the château de Mayenne, in the course of what Anne Bocquet and Jacques Naveau called "a veritable translation of the seat of power".[9] The rural nature of the bourg, however, kept the public buildings and the footprint of the ancient settlement relatively untouched.[14]

Rediscovery

By the 9th century the Diablinte settlement had been forgotten. but, starting at the end of the 16th century, commentators on Julius Caesar began trying to locate it, particularly in Brittany[15] Canon Jean Lebeuf identified the city in 1739 through a study of classical sources and information gleaned from the Roman Catholic Diocese of Le Mans.[16]

The fortuitous discovery in 1776 of a vast mosaic supported the Lebeuf theory, even though it continued to be questioned in the face of all evidence into the 19th century.[14] Other excavations in the area of La Tonnelle at the end of the 18th century unearthed important, long-known ruins,[17] which had since disappeared.

Archeological interest in Jublains was rekindled during the July Monarchy at the beginning of the 19th century, in particular for Arcisse de Caumont and Prosper Mérimée. The latter prevailed upon the departemental authorities to buy and protect the castellum.[18] In 1840, its entry onto the first list of monuments historiques assured the future of the site.

The 19th-century excavations primarily took place between 1834 and 1870 and unearthed the principal buildings of the Roman settlement. They were published in the papers of the principal protagonists: François-Jean Verger, Augustin Magdelaine and Henri Barbe[19] At the beginning of the 20th century local archeology suffered setbacks, as sites were looted for construction materials.[19]

Excavations resumed in 1942, led by Robert Boissel and René Diehl, of the temple and the baths. Roadwork between 1957 and 1969 led to some finds.[19] In the 1970s, an excavation of the southwestern necropolis and a rescue operation during work on a sports field took place.[19] By then a new generation was working in Jublains: in 1975 René Rebuffat began his masterly study of the castellum, with other researchers working on the theatre and the sanctuary.[20]

Since the 1980s, and especially since the advent of the archeological service in 1988, Mayenne has carried out land management efforts to make the ancient city more visible. Between 1990 et 1996, the municipality acquired a large tract of real estate[21] to facilitate management of the site and to create a large archeological reserve.[22] A museum opened in 1969 to exhibit Gallo-Roman artifacts discovered in Mayenne.

Since the end of the 1980s, research has focused on knowledge of the city and its layout,[20] with systematic excavations focusing on the housing and workshops of the craftsmen of the Diablint city. Research has focused on the differences between town planning and actual construction, as observed by archaeology.[23]

Buildings on the site

Urban design

Only a third of the ancient city is covered by buildings; the rest is available for archaeological research.[24] The orthogonal plan, with an area of twenty hectares, seems to date from the Flavian dynasty. While the internal organization of the insulae varies,[25] forty of them were discovered in the mid-1990s.[24]

Archeologists found the necropolis of the city, which makes it possible to place in a rather definite way the limits of the city's influence. However, traces of organization beyond its western limits have raised doubt, although archaeologists have cautiously considered these traces related to a centuriation of the surrounding countryside.[25] According to Jacques Naveau, "the main feature of this plan is the alignment of public buildings along a north-south axis, which seems central" over a length of 800 meters.[25][24] He also links this alignment to the religious origin of the city.[26]

The organisation of the urban network was along two axes seven meters wide. The side streets were 4 to 4.5 meters wide.[26] At least two stages of the development of the road system have been highlighted[26] the second stage being later than the 1st century.

The city does not seem to have had sewers in the streets, apart from wastewater drains of the bathhouse,[27] nor an aqueduct except the one underground that fed the baths on the site of the current church.

The southeastern part of the city does not seem to have seen the urbanization initially planned,[4] with the space used instead for craft purposes.[9] Workshops, including those of potters and glassmakers[24] and scattered dwellings give a total footprint for the Diablintian city of a hundred hectares.[27]

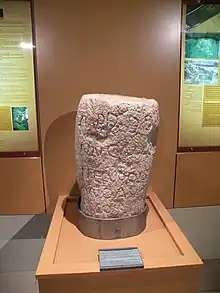

Forum

At the place called La Tonnelle, excavations in the last third of the 19th century, specifically in 1864 by Henri Barbe and then in 1865–1870 by Jean-Charles Chedeau and Charles de Sarcus, made it possible to unearth a vast porticoed space with 52 meters long from north to south (or even double) and about 55 meters wide from east to west (i.e. an area of around 3,000 m2)[8]); on its northern side it has a number of small rooms.[29] This space built in opus mixtum was interpreted as a villa. However, Jacques Naveau identified it as the location of the forum of the city. The inscriptions discovered on the site were able to confirm this identification; one, on an altar with alleyways, bore a dedication to Jupiter.[29] As the object remained in the fortress without protection, weather and the elements have made it illegible, but it is now displayed at the museum in Jublains.[30]

During his research, Henri Barbe discovered a coin bearing the portrait of Tiberius,[29] which makes it possible to envisage a construction of the whole after the reign of the latter. On the site was also discovered an inscription mentioning baths.[31]

Late 19th century construction in neo-Romanesque style on the site of the forum

Late 19th century construction in neo-Romanesque style on the site of the forum

Theatre

Acquired by the département in 1915 and registered as a monument historique en 1917,[34][35] the theatre was built around 81–83 in the reign of Domitian;[36] the dating stems from a dedication to the emperor found in the excavations, which also mentions the name of the donor.[37]

Established on a slope at the edge of town, today it faces a pastoral panorama of bocage, with the Coëvron hills in the background. It was given to the city by a rich merchant named Orgétorix, as witnessed by a fragment of an inscription found in 1989 and since placed in the museum.[30] Several such inscriptions have been found in the building.[37] This gift was an example of euergetism in an assimilating member of the Gaulish elite.

Identified in the middle of the 19th century and excavated several times, by Augustin Magdelaine (1843), Henri Barbe (circa 1865) and the service of historical monuments (1926–1928), the building was however only completely cleared in the 1980s, with a general study by Bernard Debien (1985) and then the excavations by Françoise Dumasy (1991–1995). An earlier monument, with an almost circular provincial plan, was replaced in the 2nd century, probably during the reign of Hadrian,[10] by a larger theatre with a "plan closer to the classical semi-circular model",[36][37] making it possible to give shows in an amphitheatre. Wild animal fights seem to never have taken place there, given the lack of facilities to ensure the safety of spectators.

The construction was of a type frequently used in Gaul, combining stone with extensive use of wood. Using a natural slope of the ground, the bleachers were built in the latter material.[37] The carved decoration is largely unknown. However, in the excavations of the castellum archaeologists found fragments believed to have come from the same decorative element, called "mask pillars". This decoration, evoking a theatre scene was found reused in the northeast foundations of the fortress.[38] Archaeologists also found terracotta statuettes of Venus and a monolithic Iron Age stele, which still stands to the right of the orchestra.

The place is still used for cultural events, cinema, theatre and concerts.

Fragment with the name of the theatre's benefactor, the rich merchant Orgétorix, shelly limestone. Archeological museum in Jublains[39]

Fragment with the name of the theatre's benefactor, the rich merchant Orgétorix, shelly limestone. Archeological museum in Jublains[39] Fragments of the "mask pillar", limestone, 3rd century

Fragments of the "mask pillar", limestone, 3rd century

Castellum

The castellum is a trapezoidal fortification of 117.50 × 104.25 metres. Excavated by François-Jean Verger in 1834, it was acquired in 1839 département government, at the behest of Prosper Mérimée; the construction had at that time been known since the beginning of the 18th century even though it was at first poorly identified. The first major study followed this acquisition with the excavations of Augustin Magdelaine in 1839 and of Henri Barbe in 1867. Limited research took place after the last quarter of the 19th century. But the general study of the monument was the work of René Rebuffat between 1975[40] and 1990.

The layout of the ruins reveals three phases in construction.[41] In the center, a massive rectangular praetorian tower of 22 × 23 meters[42] was built at the end of the 2nd century or the beginning of the 3rd. It had a floor, a courtyard and was flanked by powerful square corner turrets at each of its corners.[43] René Rebuffat sees it as a building of the imperial administration, perhaps linked to the service of the praefectus annonae.[44] This building could also have been used as part of the cursus publicus. Annexes were present, possibly silos,[44] and four wells equally divided between the interior and exterior.[41]

An earthen rampart preceded by a ditch ten meters wide, pierced to the south-east by a door,[42] surrounds the tower and testifies to the urgency of the security situation at the end of the 3rd century.[45] The coins discovered date this element to the period 274–285.[46] A wall of about 120 meters on each side[41] and provided with circular towers at its corners and on its faces completes the device. This wall was probably erected at the beginning of the reign of Diocletian, after filling in the ditch.[47] A round tower defends each of the four angles, five other towers being arranged on the faces.[45] These nine towers have a diameter of six to seven meters. The complex was probably never completed because the defenses to protect the entrances were never finished.[48] This state of incompleteness is perhaps due to the loss of the strategic importance of the Diablintian city in favour of the Rhine border.[10]

The construction was long considered defensive in nature, but some historians believe it was used to store grain or more precious goods such as gold or tin. It might also have served as a place to gather taxes paid in crops.[46]

Inside the enclosure are the remains of two thermal complexes, one to the northeast and the other to the southwest. The "small baths" are very simple with two rooms, one of which is on hypocaust and the other serves as a changing room and boiler room.[44] The "great thermal baths" of twelve by six meters have the main rooms of a bathhouse:[46] vestibule, frigidarium, three rooms on hypocaust (including a warm room and an oven) and a boiler room.[44]

Fragments of architectural elements from destroyed buildings, used for reuse in the masonry and foundations of the wall, were found during the excavations:[48] shafts of columns but also fragments of the "mask pillars".[49]

Thermae

The thermal baths complete the monumental adornment of the city under the reign of Trajan[34] even if works were still taking place under the Severi.[10] They were partly transformed into a church (just like at Entrammes) during Late antiquity.[10]

Although the discovery of the building dates back to road works undertaken in 1842, with an extension due to work carried out at a private home in 1863, the real opportunity to know more about the monument came amid the destruction of the former place of Catholic worship around 1878.[50] Canalization works in 1957 and then again in 1969 made it possible to complete the knowledge of the plan of the building.[50] René Diehl brought to light the remains present under the church in 1973–1974,[51] this excavation being followed by the enhancement of the remains and the opening to the public which allows the exhibition of the paved swimming pool as well as a system of hypocaust. New excavations to clarify the plan took place outside the building around the year 2000; materialized at the level of the forecourt of the main portal of the church.

The thermal baths occupied an ins ula about sixty meters wide.[52] The spa complex stood in the middle of an enclosure of porticoes; annexes completed the set. The cold bath, the warm room and the hot baths are visible today. The cold room or frigidarium has a swimming pool with an apse on its southern side. If the pool basin was larger in its initial state,[31] the renovation with shale paving dates from the second half of the 2nd century. The warm room has a hypocaust located on its periphery,[31] while to the north, 19th century excavators also highlighted a room on a hypocaust. The hot bathroom has two apses.[31] In addition, to the west, a hearth has been noted.[52]

An eight-kilometer underground aqueduct brought water to the establishment.[31] Two sewers evacuated waste water towards the theatre, one from the cold baths and the other from the hot baths.[52]

Little is known of the decorative elements, even though fragments of mosaics have been found, as well as a fragment of painted wall plaster thought to have come from the thermal baths.[52]

Swimming pool of the frigidarium with schist flooring

Swimming pool of the frigidarium with schist flooring Right wall of the baths, bordered by the sarcophagi of the Merovingian necropolis.

Right wall of the baths, bordered by the sarcophagi of the Merovingian necropolis.

Temple

First identified in 1835, then purchased and registered as a monument historique[53] in 1912,[27] the temple, known as Fortuna, nowadays consists of the Roman remains of a sanctuary that succeeded the Gallic place of worship. The temple was built, then demolished, then rebuilt, then burned to the ground and demolished again.[54]

The site was excavated many times in the 19th and 20th centuries, by:

- François-Jean Verger (1835–1839)

- Augustin Magdelaine (1843)

- Henri Barbe (1855–1867 and 1903)

- Julien Chappée and Reboursier (1906–1912)

- Robert Boissel and Yves Lavoquer (1942)

- Robert Boissel (1943–1946)

- André Pioger (1952–1957)

- Jacques Naveau (1986–1991).

After the first stratigraphic excavations in 1942, the last excavations were carried out at the end of the 1980s, enabling the site to be restored and developed for public access.

The site consisted of an enclosure of about 70 metres on each side.[55] The periphery of the courtyard was marked by porticoes, some of which remain to the southwest. In the center was the temple stricto sensu.

Temple at Jublains

Temple at Jublains Jublains temple, southeast

Jublains temple, southeast Access ramp to the temple

Access ramp to the temple Mock-up of the temple in the museum

Mock-up of the temple in the museum

The sanctuary has two entrances, the main one through corridor reached by a staircase. Outside is a structure intended for ablutions. The water supply of this space comes through an underground pipe from the temple.[56][57] The hypothesis of a sanctuary dedicated to a goddess linked to a spring collides with the scarcity of available water. The facilities seem designed to collect scarce water.[29] The deity to whom the sanctuary whom dedicated is not known. Archaeologists have evoked an indigenous deity related to Mars, or even a mother goddess, based on statue fragments and the Venus made of white earth discovered there, belonging to a related trade, it seems, at the sanctuary.[58]

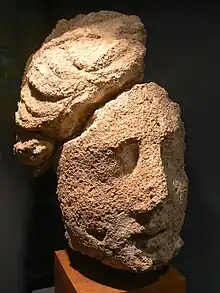

Excavations have uncovered many fragmentary offerings: Celtic offerings followed by bronze items whose purpose was exclusively votive.[59] The inner construction used local stone, while shelly limestone from the Loire was used to dress the exterior walls.[57] The columns of the peribolos were cut from grès quarried a dozen kilometers away,[27] while the capitals were tuffeau stone. Decorative elements from the sanctuary are now exhibited in the museum, including the head of a mother-goddess statue in shelly limestone.[60] Fragments of frescoes have also been found; one of them represents a pigeon and decorated one of the entrances to the peribolos.[61]

The temple itself is slightly off-center towards the south-west. This configuration can perhaps be tied to re-use of construction materials from an earlier edifice of impermanent materials, or to a need for a gathering place for processions.[55]

The current ruins belong to the podium of an octastyle peripteros, more precisely the soubassement underpinnings of a cella.[62] The temple was thirty by twenty meters, and the cella was surrounded by a gallery.[55]

Coins bearing the portrait of Nero, from after AD 65, have fixed the date of the replacement by a stone edifice of the original Gaulish construction.[63][55] Work was done on the above-ground parts of the temple, no doubt in the reign of the Sévères.[56] Archaeologists have dated the damage to the entrance porches to the end of the 3rd century. The fragments of the goddess-mother came from the masonry there.[64] A coin dating from the reign of Magnentius discovered in the 1959 excavations attests to a later partial unearthing.[29] The location was abandoned circa 350.[57]

Habitat

For a long time excavations focused on the public buildings, even though living quarters were uncovered on several occasions. Research on the city has expanded since 1990, in conjunction with the real estate acquisitions and a rigorous excavation program.[21]

The layout of the ancient city is relatively well known, even if the details of its organization into insulae have not yet been established.[65] The best-known spaces are away from the location of the current town. Of the spaces which have been studied so far, the dwelling at La Boissière was excavated from 1972 to 1979 and yielded pottery from the La Tène culture. The building dates from the 1st century and in addition to the main building has outbuildings, that include two wells. Nodified in the 3rd century, it was organized around a closed inner courtyard, and occupied until the Middle Ages.[66] The La Tonnelle house, between the temple and the forum, was excavated around 1834 and again 1864–1870.[67] Statuettes of Venus and edifices, one resembling a fanum were found. Aerial archaeology also took place, in particular in 1889.[68]

Only one mosaic has been found, in 1776 in the area known as Clos aux Poulains. Probably coming from a thermal building,[69] it was destroyed during the French Revolution.[70] Other excavations took place in the area at the same time as those at La Tonnelle.[71]

Traces of pottery and metalworking have been found in the southwest area of the site,[72] but it is very sparsely built up, unlike the southeast, which is densely built up. Traces of housing and artisanal occupations have also surfaced beyond the limits of the site.[73]

La Boissière, with a ruined well in the foreground, La Tonnelle house on the site of the forum (rear)

La Boissière, with a ruined well in the foreground, La Tonnelle house on the site of the forum (rear)![Mosaic discovered in 1776, drawing by Jean Lair de la Motte [fr], published in Henri Barbe's 1865 work](../I/Jublains_Mosa%C3%AFque_1776.jpg.webp) Mosaic discovered in 1776, drawing by Jean Lair de la Motte, published in Henri Barbe's 1865 work

Mosaic discovered in 1776, drawing by Jean Lair de la Motte, published in Henri Barbe's 1865 work Fragment of the same mosaic, in the museum

Fragment of the same mosaic, in the museum

Necropoles

In the Roman world, necropoles were located outside the cities. Those of the Diablint city are not completely known today. However, the perimeter of the ancient site is relatively secure.[24]

The best known "southern necropolis" was located on the site of the departmental archaeological museum. Excavations carried out between 1969 and 1972 revealed a large majority of cremation burials,[74] dated from the 1st to the 4th century.[24] According to the findings of 19th century archaeologists, another necropolis existed near the temple.[24] In its vicinity there was probably a mausoleum to which belonged a representation of Oceanus, now on display in the museum. Scattered elements have also been found elsewhere on the site.[75]

See also

- Musée archéologique départemental de Jublains

- Vieux-la-Romaine

- Sanctuaire de Ribemont-sur-Ancre

- List of Roman names of French cities

References

Citations

- Quintela et al. 2022.

- Base Mérimée: PA00109515, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Naveau 1992, p. 42

- Bocquet & Naveau 2003, p. 17

- "Au milieu des terres par rapport aux Vénètes, vers l'est, sont les Aulerques Diablintes, dont la ville est Noviodunum" (to the east of the [[Veneti (Gaul)}|Veneti]] were the Diablintes, whose city is Noviodunum): Ptolemy, Géographie, II, 8, 7, cited par Jacques Naveau (1997). Sources et recherches sur Jublains et sa cité [Geography]. Documents archéologiques de l'Ouest. Rennes: Revue archéologique de l'Ouest. p. 15.

- Naveau 1997, p. 16

- see Vieux-la-Romaine

- Golvin 2003, p. 183

- Bocquet & Naveau 2003, p. 18

- Naveau 1992, p. 43

- Monteil 2017, pp. 15–37.

- Naveau 1995, p. 34

- Renoux 2000, p. 217

- Naveau 1997, p. 9

- Naveau 1997, p. 23

- Naveau 1997, pp. 23–24

- Naveau 1997, p. 24

- Naveau 1997, p. 25

- Naveau 1997, p. 26

- Naveau 1997, p. 27

- Naveau 1997, p. 10

- Naveau 1997, p. 70

- Naveau 1998, p. 8

- Naveau 1995, p. 27

- Naveau 1992, p. 44

- Naveau 1992, p. 46

- Naveau 1992, p. 48

- Naveau 1992, p. 51

- Naveau 1998, p. 100

- Naveau 1995, p. 29

- Naveau 1997 p.21

- CIL, XIII-1, 3184

- Naveau 1992, p. 54

- Base Mérimée: PA00109517, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Naveau 1992, p. 55

- Naveau 1995, p. 26

- Naveau 1998, pp. 126–127

- CIL, XIII-1, 3187

- Naveau 1992, p. 56

- Naveau 1995, p. 31

- Beck 1986, p. 11.

- Naveau 1992, p. 57

- Naveau 1992, p. 58.

- Naveau 1992, p. 59.

- Naveau 1995, p. 32

- Naveau 1995, pp. 32–33

- Naveau 1995, p. 33.

- Naveau 1992, p. 60.

- Naveau 1992, p. 52

- Naveau 1992, pp. 52–53

- Naveau 1992, p. 53

- Base Mérimée: PA00109516, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Boissel & Lavoquer 1943.

- Naveau 1995, p. 23

- Naveau 1992, p. 50

- Naveau 1995, p. 24

- Naveau 1995, p. 22

- Naveau 1995, p. 21

- Naveau 1998, p. 81

- Naveau 1998, p. 82

- Naveau 1992, p. 49

- Naveau 1992, pp. 49–50

- Naveau 1992, pp. 50–51

- Naveau 1992, p. 61

- Naveau 1992, p. 65

- Naveau 1992, pp. 65–66

- Naveau 1992, p. 66

- Naveau 1992, p. 67

- Naveau 1992, p. 78

- Naveau 1992, p. 68

- Naveau 1992, p. 71

- Naveau 1992, pp. 72–73

- Naveau 1992, p. 73

- Naveau 1992, p. 75

Bibliography

- Beck, Bernard (1986). Châteaux-forts de Normandie [Fortified castles of Normandy] (in French). Rennes: Ouest-France. ISBN 2-85882-479-7.

- Boissel, R.; Lavoquer, Y. (1943). "Maine: les fouilles du temple de jublains". Gallia. CNRS Editions. 1 (2): 266–273. JSTOR 43603040.

- Chuniaud, Kristell; Bocquet, Anne; Naveau, Jacques (2004). "Le quartier antique de la Grande-Boissière à Jublains (Mayenne)". Revue archéologique de l'Ouest (in French). 21: 131–174. doi:10.3406/rao.2004.1177. ISSN 0767-709X.

- Bocquet, Anne; Naveau, Jacques (2003). Jublains/Noviodunum. Vol. 66. pp. 17–18.

- Golvin, Jean-Claude (2003). L'antiquité retrouvée [Antiquity Rediscovered] (in French). Paris: Errance. p. 183. ISBN 978-2-87772-266-7.

- Monteil, Martial (2017). "Les agglomérations de la province de Lyonnaise Troisième (Bretagne et Pays de la Loire): Entre abandon, perduration et nouvelles créations (III e -VI e S. apr. J.-C.)". Gallia (in French). CNRS Editions. 74 (1). doi:10.4000/gallia.2329. JSTOR 44843902. S2CID 192830079.

- Naveau, Jacques (1995). Jublains, ville et forteresse [Jublains, City and Fortresss]. Vol. 14. pp. 19–34.

- Naveau, Jacques (1992). La Mayenne. Carte archéologique de la Gaule 53 (in French). Paris: Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres. ISBN 978-2-87754-015-5. OCLC 463674282.

- Naveau, Jacques (1997). Recherches sur Jublains (Mayenne) et sur la cité des Diablintes [Research on Jublains (Mayenne) and on the Diablinte Settlement]. Documents Archéologiques de l'Ouest (in French). Rennes. OCLC 489679956.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jacques Naveau and Bertrand Bouflet, La Mayenne au fil du temps: l'archéologue et le photographe (Mayenne in the Course of Time: The Archaeologist and the Photographer), published by Siloë, Laval, 1999

- Jacques Naveau, La ruine envisagée comme relique: le cas du temple de Jublains (Ruin Seen As Relic: The Case of the Temple of Jublains), collection Actes des colloques de la Direction du patrimoine, published by Ministère de la culture, Paris, 1991, pp. 93–95

- Jacques Naveau, Carte archéologique de la Gaule (Archaeological Map of Gaul) 53: La Mayenne, Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, 1992, 1st edition, 176 pp. (ISBN 978-2-87754-015-5).

- Naveau, Jacques (1998). Le chasseur, l'agriculteur et l'artisan. Guide du musée archéologique de Jublains [The Hunter, the Farmer and the Artisan: Guide to the Archaeological Museum of Jublains] (in French). Laval: Conseil général de la Mayenne. p. 174. ISBN 978-2-9513333-0-7.

- Quintela, Marco V. García; González-García, A. César; Espinosa-Espinosa, David; Rodríguez-Antón, Andrea; Belmonte, Juan A. (2022). "An Archaeology of the Sky in Gaul in the Augustan Period". Journal of Skyscape Archaeology. 8 (2): 163–207. doi:10.1558/jsa.21048. S2CID 256885858.

- Renoux, Annie (2000). "« Mayenne: de la villa au castrum (VII–XIIIe siècle)" [Mayenne: From the Villa to the Castrum (7th to 8th century)]. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Comptes-rendus des séances de l'année... - Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. 144 (1): 211–231. doi:10.3406/crai.2000.16113.

- François-Jean Verger, Fouilles faites à Jublains en avril 1840 (Excavations Carried out at Jublains in April 1840), published by Imprimerie de Honoré Godbert, Laval, 1840

- Collectif, Jublains, ville romaine. Guide du visiteur (Jublains, Roman City. Visitor's Guide , published by the Conseil général de Mayenne, Laval, date unknown

Further reading

- Barbe, Henri (1865). Jublains (Mayenne): notes sur ses antiquités, époque gallo-romaine pour servir a l'histoire et à la géographie de la ville et de la cité des Aulerges-Dialante. Accompagné d'un atlas, de plans et de dessins (in French). Mayenne: Imprint de A. Derenne, Le Mans, Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon (Bibliothèque jésuite des Fontaines).

- Bocquet, Anne; Jacques, Naveau (2004). "Jublains (Mayenne), capitale d'une cité éphémère". Capitales éphémères: des capitales de cités perdent leur statut dans l'Antiquité tardive ; actes du colloque organisé par le Laboratoire Archéologie et Territoires (UMR CITERES), Tours, 6 - 8 mars 2003 ; atlas des capitales éphémères. Supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France. Vol. 25. Tours: Fédération pour l'édition de la Revue archéologique du Centre de la France. pp. 173–182, 435–438. ISBN 9782913272101.

- Boissel, René; Naveau, Jacques (1930). "Les fouilles du terrain de sport de Jublains (Mayenne), 1972-1979". La Mayenne: Archéologie, Histoire. 2: 3–34.

- Bonaventure, Martine (1930). "Découverte d'une stèle dans le théâtre de Jublains (Mayenne)". La Mayenne: Archéologie, Histoire. 11: 43–46.

- Cormier, Sébastien. 'Les décors antiques de l'ouest de la Gaule lyonnaise (PDF) (Doctoral). University of Maine, Le Mans.

- Diehl, René (1984). "Les thermes de Jublains". La Mayenne: Archéologie, Histoire (6): 57–78.

- Guillier, Gérard; Delage, Richard; Besombes, Paul-André (20 December 2008). "Une fouille en bordure des thermes de Jublains (Mayenne): enfin un dodécaèdre en contexte archéologique !". Revue archéologique de l'Ouest (25): 269–289. doi:10.4000/rao.680.

- Napoli, Joëlle (1 July 2003). "Le complexe fortifié de Jublains et la défense du littoral de la Gaule du Nord". Revue du Nord. n° 351 (3): 611–629. doi:10.3917/rdn.351.0611.

- Naveau, Jacques (1988). "Au confluent de l'histoire et de l'archéologie: la localisation des Diablintes et de Noviodunum (Jublains)". La Mayenne: Archéologie, histoire (in French). la Société d'archéologie et d'histoire de la Mayenne (11): 11–42.

- Naveau, Jacques (June 1986). "Jublains ou l'échec d'une ville". Dossiers Histoire et Archéologie (106): 30–33.

- Naveau, Jacques (2004). "Jublains, capitale disparue". La Mayenne: Archéologie, Histoire. 27: 276–312.

- Naveau, Jacques (February 2000). "Gérer un site départemental". Dossiers d'Archéologie (in French) (250): 62–65. ISSN 1141-7137.

- Naveau, Jacques (2006). Jublains, les fortunes d'une capitale antique [Jublains: The Fortunes of a Capital of Antiquity]. Vol. 92.

- Rebuffat, R. (1985). "Jublains: Un Complexe Fortifié Dans L'ouest De La Gaule". Revue Archéologique. Presses Universitaires de France (2): 237–256. ISSN 0035-0737. JSTOR 41736275.

- Rebuffat, René (1997). "Le complexe fortifié". In Naveau, J. (ed.). Recherches sur Jublains (Mayenne) et sur la cité des Diablintes, Documents archéologiques de l'Ouest (in French). Rennes: Association pour la diffusion des recherches archéologiques dans l'ouest de la France. pp. 255–338.

- Reddé, Michel; Brulet, Raymond; Fellmann, Rudolf; Jan-Kees, Haalebos; Von Schnurbein, Siegmar; Aupert, Pierre, eds. (2006). L'architecture de la Gaule romaine — Les fortifications militaires. Documents d’archéologie française | 100 (in French). Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme. pp. 300–301. doi:10.4000/books.editionsmsh.22093. ISBN 9782735111190. S2CID 193996901.

- Sevestre, Aurelia (2006). "Jublains capitale des Diablintes" [Jublains Capital of the Diablintes]. Itinéraires de Normandie. 3: 35–41.

External links

- Official website of the Jublains archaeological site (in French)

- Diaporama des vestiges antiques (Encyclopédie du patrimoine architectural français , (Encyclopedia of the French archaeological patrimony))

- Jublains materials on the website of the Académie de Nantes (in particular plans de localisation et du site archéologique)

- Jublains Archived 2012-10-18 at the Wayback Machine on the website of the Orléans section of the Association Guillaume Budé

- Gérard Guillier, Richard Delage and Paul-André Besombes, Une fouille en bordure des thermes de Jublains (Mayenne): enfin un dodécaèdre en contexte archéologique! (An excavation next to the baths of Jublains (Mayenne): Finally a dodecahedron in an archaeological context)

- Découverte d'une rue commerçante gallo-romaine à Jublains, Les Alpesmancelles.fr, 04/05/2015 (Discovery of a Gallo-Roman commercial street at Julains)