Judith beheading Holofernes

The account of the beheading of Holofernes by Judith is given in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, and is the subject of many paintings and sculptures from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the story, Judith, a beautiful widow, is able to enter the tent of Holofernes because of his desire for her. Holofernes was an Assyrian general who was about to destroy Judith's home, the city of Bethulia. Overcome with drink, he passes out and is decapitated by Judith; his head is taken away in a basket (often depicted as being carried by an elderly female servant).

Artists have mainly chosen one of two possible scenes (with or without the servant): the decapitation, with Holofernes supine on the bed, or the heroine holding or carrying the head, often assisted by her maid.

In European art, Judith is very often accompanied by her maid at her shoulder, which helps to distinguish her from Salome, who also carries her victim's head on a silver charger (plate). However, a Northern tradition developed whereby Judith had both a maid and a charger, taken by Erwin Panofsky as an example of the knowledge needed in the study of iconography.[1] For many artists and scholars, Judith's sexualized femininity sometimes contradictorily combined with her masculine aggression. Judith was one of the virtuous women whom Van Beverwijck mentioned in his published apology (1639) for the superiority of women to men,[2] and a common example of the Power of Women iconographic theme in the Northern Renaissance.

Background in early Christianity

The Book of Judith was accepted by Jerome as canonical and accepted in the Vulgate and was referred to by Clement of Rome in the late first century (1 Clement 55), and thus images of Judith were as acceptable as those of other scriptural women. In early Christianity, however, images of Judith were far from sexual or violent: she was usually depicted as "a type of the praying Virgin or the church or as a figure who tramples Satan and harrows Hell," that is, in a way that betrayed no sexual ambivalence: "the figure of Judith herself remained unmoved and unreal, separated from real sexual images and thus protected."[3]

Renaissance depictions

Judith and Holofernes, the famous bronze sculpture by Donatello, bears the implied allegorical subtext that was inescapable in Early Renaissance Florence, that of the courage of the commune against tyranny.[4]

In the late Renaissance, Judith changed considerably, a change described as a "fall from grace"—from an image of Mary she turns into a figure of Eve.[5] Early Renaissance images of Judith tend to depict her as fully dressed and desexualized; besides Donatello's sculpture, this is the Judith seen in Sandro Botticelli's The Return of Judith to Bethulia (1470–1472), Andrea Mantegna's Judith and Holofernes (1495, with a detached head), and in the corner of Michelangelo's Sistine chapel (1508–1512). Later Renaissance artists, notably Lucas Cranach the Elder, who with his workshop painted at least eight Judiths, showed a more sexualized Judith, a "seducer-assassin": "the very clothes that had been introduced into the iconography to stress her chastity become sexually charged as she exposes the gory head to the shocked but fascinated viewer", in the words of art critic Jonathan Jones.[6] This transition, from a desexualized image of Virtue to a more sexual and aggressive woman, is signaled in Giorgione's Judith (c. 1505): "Giorgione shows the heroic instance, the triumph of victory by Judith stepping on Holofernes's severed, decaying head. But the emblem of Virtue is flawed, for the one bare leg appearing through a special slit in the dress evokes eroticism, indicates ambiguity and is thus a first allusion to Judith's future reversals from Mary to Eve, from warrior to femme fatale."[5] Other Italian painters of the Renaissance who painted the theme include Botticelli, Titian, and Paolo Veronese.

Especially in Germany an interest developed in female "worthies" and heroines, to match the traditional male sets. Subjects combining sex and violence were also popular with collectors. Like Lucretia, Judith was the subject of a disproportionate number of old master prints, sometimes shown nude. Barthel Beham engraved three compositions of the subject, and other of the "Little Masters" did several more. Jacopo de' Barberi, Girolamo Mocetto (after a design by Andrea Mantegna), and Parmigianino also made prints of the subject.

Baroque depictions

Judith remained popular in the Baroque period, but around 1600, images of Judith began to take on a more violent character, "and Judith became a threatening character to artist and viewer."[3] Italian painters including Caravaggio, Leonello Spada, and Bartolomeo Manfredi depicted Judith and Holofernes; and in the north, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and Eglon van der Neer[7] used the story. The influential composition by Cristofano Allori (c. 1613 onwards), which exists in several versions, copied a conceit of Caravaggio's recent David with the Head of Goliath: Holofernes' head is a portrait of the artist, Judith is his ex-mistress, and the maid her mother.[3][8] In Artemisia Gentileschi's painting Judith Slaying Holofernes (Naples), she demonstrates her knowledge of the Caravaggio Judith Slaying Holofernes of 1612; like Caravaggio, she chooses to show the actual moment of the killing.[9] A different composition in the Pitti Palace in Florence shows a more traditional scene with the head in a basket.

While many of the above paintings resulted from private patronage, important paintings and cycles were made also by church commission and were made to promote a new allegorical reading of the story—that Judith defeats Protestant heresy. This is the period of the Counter-Reformation, and many images (including a fresco cycle in the Lateran Palace commissioned by Pope Sixtus V and designed by Giovanni Guerra and Cesare Nebbia) "proclaim her rhetorical appropriation by the Catholic or Counter-Reformation Church against the 'heresies' of Protestantism. Judith saved her people by vanquishing an adversary she described as not just one heathen but 'all unbelievers' (Jdt 13:27); she thus stood as an ideal agent of anti-heretical propaganda."[10]

When Rubens began commissioning reproductive prints of his work, the first was an engraving by Cornelius Galle the Elder, done "somewhat clumsily",[11] of his violent Judith Slaying Holofernes (1606–1610).[12] Other prints were made by such artists as Jacques Callot.

Modern depictions

The allegorical and exciting nature of the Judith and Holofernes scene continues to inspire artists. In the late nineteenth century, Jean-Charles Cazin made a series of five paintings tracing the narrative and giving it a conventional, nineteenth-century ending; the final painting shows her "in her honoured old age", and "we shall see her sitting in her house spinning".[13]

Two notable paintings of Judith were made by Gustav Klimt. The story was quite popular with Klimt and his contemporaries, and he painted Judith I in 1901, as a dreamy and sensual woman with open shirt. His Judith II (1909) is "less erotic and more frightening". The two "suggest 'a crisis of the male ego', fears and violent fantasies all entangled with an eroticized death, which women and sexuality aroused in at least some men around the turn of the century."[14]

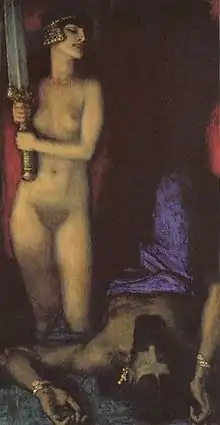

Modern paintings of the scene often cast Judith nude, as was signalled already by Klimt. Franz Stuck's 1928 Judith has "the deliverer of her people" standing naked and holding a sword besides the couch on which Holofernes, half-covered by blue sheets[15]—where the text portrays her as god-fearing and chaste, "Franz von Stuck's Judith becomes, in dazzling nudity, the epitome of depraved seduction."[16]

In 1997, Russian artists Vitaliy Komar and Alexander Melamed painted a Judith on the Red Square that "casts Stalin in the Holofernes role, conquered by a young Russian girl who contemplates his severed head with a mixture of curiosity and satisfaction".[17] In 1999, American artist Tina Blondell rendered Judith in watercolour; her I'll Make You Shorter by a Head [18] is explicitly inspired by Klimt's Judith I, and part of a series of paintings called Fallen Angels.[19]

Gallery

12th-century French ivory gaming piece, found in Bayeux in 1838

12th-century French ivory gaming piece, found in Bayeux in 1838 Donatello, Judith and Holofernes, 1457–64

Donatello, Judith and Holofernes, 1457–64 Sandro Botticelli, The Return of Judith to Bethulia, 1470

Sandro Botticelli, The Return of Judith to Bethulia, 1470 Andrea Mantegna, Judith and Holofernes, 1490s

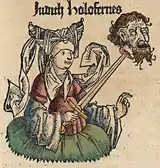

Andrea Mantegna, Judith and Holofernes, 1490s Woodcut illustration for the Nuremberg Chronicles, 1493

Woodcut illustration for the Nuremberg Chronicles, 1493 Alabaster figure by Conrad Meit, c. 1525

Alabaster figure by Conrad Meit, c. 1525 Judith with the Head of Holophernes, by Hans Baldung Grien, c. 1525, Germanisches Nationalmuseum.

Judith with the Head of Holophernes, by Hans Baldung Grien, c. 1525, Germanisches Nationalmuseum. Sebald Beham engraving of 1547

Sebald Beham engraving of 1547

Michelangelo, Judith carrying away the head of Holofernes, in the Sistine Chapel (1508–1512)

Michelangelo, Judith carrying away the head of Holofernes, in the Sistine Chapel (1508–1512) Stained glass window, c. 1510–1530

Stained glass window, c. 1510–1530 Fede Galizia, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1596

Fede Galizia, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1596.jpg.webp) Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1598–1599)

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1598–1599) Giovanni Baglione, Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1608)

Giovanni Baglione, Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1608) Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (c. 1625)

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (c. 1625) Carlo Saraceni, Judith and the head of Holofernes (c. 1615)

Carlo Saraceni, Judith and the head of Holofernes (c. 1615) Antiveduto Grammatica, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1620–1625)

Antiveduto Grammatica, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1620–1625) Antonio Gionima, Judith Presenting Herself to Holofernes (1720s). Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Antonio Gionima, Judith Presenting Herself to Holofernes (1720s). Minneapolis Institute of Art. Francisco Goya, Judith and Holofernes (1819–23)

Francisco Goya, Judith and Holofernes (1819–23) August Riedel, Judith (1840)

August Riedel, Judith (1840)

Paul Albert Steck, Judith (c. 1900)

Paul Albert Steck, Judith (c. 1900).jpg.webp) Gustav Klimt, Judith I (1901)

Gustav Klimt, Judith I (1901) Gustav Klimt, Judith II (1909)

Gustav Klimt, Judith II (1909) Raja Ravi Varma, Judith, 1889

Raja Ravi Varma, Judith, 1889 Simon Vouet, Judith with the Head of Holophernes

Simon Vouet, Judith with the Head of Holophernes Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530

Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530 Toinette Larcher after Giorgione, Judith, 18th century, engraving with etching, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

Toinette Larcher after Giorgione, Judith, 18th century, engraving with etching, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

See also

References

- Panofsky, Erwin (1939). Studies in iconology : humanistic themes in the art of the Renaissance. New York: Harper and Row. pp. 12–14. ISBN 9780064300254.

- Loughman & J.M. Montias (1999), Public and Private Spaces: Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses, p. 81.

- Wills, Lawrence Mitchell (1995). "The Judith Novel". The Jewish Novel in the Ancient World. Ithaca: Cornell UP. ISBN 978-0-8014-3075-6.

- Schneider, Laurie (1976). "Some Neoplatonic Elements in Donatello's Gattamelata and Judith and Holofernes". Gazette des Beaux-Arts: 41–48.

- Peters, Renate (2001). "The Metamorphoses of Judith in Literature and Art: War by Other Means". In Andrew Monnickendam (ed.). Dressing Up for War: Transformations of Gender and Genre in the Discourse and Literature of War. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 111–26. ISBN 978-90-420-1367-4.

- Jones, Jonathan (2004-01-10). "Judith with the Head of Holofernes, Lucas Cranach the Elder (c1530)". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- "Judith, about 1678, Eglon Hendrik van der Neer". National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- Whitaker, Lucy; Clayton, Martin (2007). The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection; Renaissance and Baroque. Royal Collection. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-902163-29-1.

- Salomon, Nanette (2006). "Judging Artemisia: A Baroque Woman in Modern Art History". In Mieke Bal (ed.). The Artemisia Files: Artemisia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. U of Chicago P. pp. 33–62. ISBN 978-0-226-03582-6.

- Ciletti, Elena (2010). "Judith Imagery as Catholic Orthodoxy in Counter-Reformation Italy". In Kevin R. Brine (ed.). The Sword of Judith: Judith Studies Across the Disciplines. Elena Ciletti, Henrike Lähnemann. Cambridge: Open Book. ISBN 978-1-906924-17-1.

- Duplessis, Georges (1886). The Wonders of Engraving. C. Scribner & Co. p. 135.

- Russell, H. Diane (1990). Eva/Ave; Women in Renaissance and Baroque Prints. Washington: National Gallery of Art/The Feminist Press. ISBN 978-0-89468-157-8.

- Child, Theodore (May 1890). "Some Modern French Painters". Harper's Magazine. pp. 817–42. Retrieved 2009-09-09. p. 830.

- Whalen, Robert Weldon (2007). Sacred Spring: God and the Birth of Modernism in Fin de Siècle Vienna. Eerdmans. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8028-3216-0.

- "Fortune in Pictures at Art Institute". The Milwaukee Journal. 12 February 1928. pp. VII.2. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Schumann-Bacia, Eva (8 December 2009). "Salome fordert den Kopf. Kunstbuch: Joachims Nagels Femme fatale – Faszinierende Frauen". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

Judith, im apokryphen Text noch gottesfürchtig und keusch, wird bei Franz von Stuck in blendender Nacktheit zum Inbegriff lasterhafter Verführung.

- Harrison, Helen A. (1997-06-22). "Works Invoking Christian Ritual". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- Minneapolis Institute of Art. "I'll Make You Shorter by a Head (Judith I)". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Sarah Henrich, "Living on the Outside of Your Skin: Gustav Klimt and Tina Blondell Show Us Judith", in Jensen, Robin M.; Kimberly J. Vrudny (2009). Visual Theology: Forming and Transforming the Community Through the Arts. Liturgical Press. pp. 13–27. ISBN 978-0-8146-5399-9.

External links

Media related to Judith and Holofernes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Judith and Holofernes at Wikimedia Commons