Perfect fourth

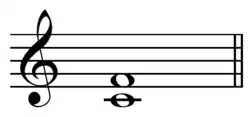

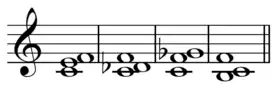

A fourth is a musical interval encompassing four staff positions in the music notation of Western culture, and a perfect fourth (ⓘ) is the fourth spanning five semitones (half steps, or half tones). For example, the ascending interval from C to the next F is a perfect fourth, because the note F is the fifth semitone above C, and there are four staff positions between C and F. Diminished and augmented fourths span the same number of staff positions, but consist of a different number of semitones (four and six, respectively).

| Inverse | perfect fifth |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | diatessaron |

| Abbreviation | P4 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 5 |

| Interval class | 5 |

| Just interval | 4:3 |

| Cents | |

| Equal temperament | 500 |

| Just intonation | 498 |

The perfect fourth may be derived from the harmonic series as the interval between the third and fourth harmonics. The term perfect identifies this interval as belonging to the group of perfect intervals, so called because they are neither major nor minor.

A perfect fourth in just intonation corresponds to a pitch ratio of 4:3, or about 498 cents (ⓘ), while in equal temperament a perfect fourth is equal to five semitones, or 500 cents (see additive synthesis).

Until the late 19th century, the perfect fourth was often called by its Greek name, diatessaron.[1] Its most common occurrence is between the fifth and upper root of all major and minor triads and their extensions.

An example of a perfect fourth is the beginning of the "Bridal Chorus" from Wagner's Lohengrin ("Treulich geführt", the colloquially-titled "Here Comes the Bride"). Another example is the beginning melody of the State Anthem of the Soviet Union. Other examples are the first two notes of the Christmas carol "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing" and "El Cóndor Pasa", and, for a descending perfect fourth, the second and third notes of "O Come All Ye Faithful".

The perfect fourth is a perfect interval like the unison, octave, and perfect fifth, and it is a sensory consonance. In common practice harmony, however, it is considered a stylistic dissonance in certain contexts, namely in two-voice textures and whenever it occurs "above the bass in chords with three or more notes".[2] If the bass note also happens to be the chord's root, the interval's upper note almost always temporarily displaces the third of any chord, and, in the terminology used in popular music, is then called a suspended fourth.

Conventionally, adjacent strings of the double bass and of the bass guitar are a perfect fourth apart when unstopped, as are all pairs but one of adjacent guitar strings under standard guitar tuning. Sets of tom-tom drums are also commonly tuned in perfect fourths. The 4:3 just perfect fourth arises in the C major scale between F and C.[3] ⓘ

History

The use of perfect fourths and fifths to sound in parallel with and to "thicken" the melodic line was prevalent in music prior to the European polyphonic music of the Middle Ages.

In the 13th century, the fourth and fifth together were the concordantiae mediae (middle consonances) after the unison and octave, and before the thirds and sixths. The fourth came in the 15th century to be regarded as dissonant on its own, and was first classed as a dissonance by Johannes Tinctoris in his Terminorum musicae diffinitorium (1473). In practice, however, it continued to be used as a consonance when supported by the interval of a third or fifth in a lower voice.[4]

Modern acoustic theory supports the medieval interpretation insofar as the intervals of unison, octave, fifth and fourth have particularly simple frequency ratios. The octave has the ratio of 2:1, for example the interval between a' at A440 and a'' at 880 Hz, giving the ratio 880:440, or 2:1. The fifth has a ratio of 3:2, and its complement has the ratio of 3:4. Ancient and medieval music theorists appear to have been familiar with these ratios, see for example their experiments on the monochord.

In the years that followed, the frequency ratios of these intervals on keyboards and other fixed-tuning instruments would change slightly as different systems of tuning, such as meantone temperament, well temperament, and equal temperament were developed.

In early western polyphony, these simpler intervals (unison, octave, fifth and fourth) were generally preferred. However, in its development between the 12th and 16th centuries:

- In the earliest stages, these simple intervals occur so frequently that they appear to be the favourite sound of composers.

- Later, the more "complex" intervals (thirds, sixths, and tritones) move gradually from the margins to the centre of musical interest.

- By the end of the Middle Ages, new rules for voice leading had been laid, re-evaluating the importance of unison, octave, fifth and fourth and handling them in a more restricted fashion (for instance, the later forbidding of parallel octaves and fifths).

The music of the 20th century for the most part discards the rules of "classical" Western tonality. For instance, composers such as Erik Satie borrowed stylistic elements from the Middle Ages, but some composers found more innovative uses for these intervals.

Middle Ages

In medieval music, the tonality of the common practice period had not yet developed, and many examples may be found with harmonic structures that are built on fourths and fifths. The Musica enchiriadis of the mid-10th century, a guidebook for musical practice of the time, described singing in parallel fourths, fifths, and octaves. This development continued, and the music of the Notre Dame school may be considered the apex of a coherent harmony in this style.

For instance, in one "Alleluia" (![]() Listen) by Pérotin, the fourth is favoured. Elsewhere, in parallel organum at the fourth, the upper line would be accompanied a fourth below. Also important was the practice of Fauxbourdon, which is a three-voice technique (not infrequently improvisatory) in which the two lower voices proceed parallel to the upper voice at a fourth and sixth below. Fauxbourdon, while making extensive use of fourths, is also an important step towards the later triadic harmony of tonality, as it may be seen as a first inversion (or 6/3) triad.

Listen) by Pérotin, the fourth is favoured. Elsewhere, in parallel organum at the fourth, the upper line would be accompanied a fourth below. Also important was the practice of Fauxbourdon, which is a three-voice technique (not infrequently improvisatory) in which the two lower voices proceed parallel to the upper voice at a fourth and sixth below. Fauxbourdon, while making extensive use of fourths, is also an important step towards the later triadic harmony of tonality, as it may be seen as a first inversion (or 6/3) triad.

This parallel 6/3 triad was incorporated into the contrapuntal style at the time, in which parallel fourths were sometimes considered problematic, and written around with ornaments or other modifications to the Fauxbourdon style. An example of this is the start of the Marian-Antiphon Ave Maris Stella (![]() Listen) by Guillaume Dufay, a master of Fauxbourdon.

Listen) by Guillaume Dufay, a master of Fauxbourdon.

Renaissance and Baroque

The development of tonality continued through the Renaissance until it was fully realized by composers of the Baroque era.

As time progressed through the late Renaissance and early Baroque, the fourth became more understood as an interval that needed resolution. Increasingly the harmonies of fifths and fourths yielded to uses of thirds and sixths. In the example, cadence forms from works by Orlando di Lasso and Palestrina show the fourth being resolved as a suspension. (![]() Listen)

Listen)

In the early Baroque music of Claudio Monteverdi and Girolamo Frescobaldi triadic harmony was thoroughly utilized. Diatonic and chromatic passages strongly outlining the interval of a fourth appear in the lamento genre, and often in passus duriusculus passages of chromatic descent. In the madrigals of Claudio Monteverdi and Carlo Gesualdo the intensive interpretation of the text (word painting) frequently highlights the shape of a fourth as an extremely delayed resolution of a fourth suspension. Also, in Frescobaldi's Chromatic Toccata of 1635 the outlined fourths overlap, bisecting various church modes.

In the first third of the 18th century, ground-laying theoretical treatises on composition and harmony were written. Jean-Philippe Rameau completed his treatise Le Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels (the theory of harmony reduced to its natural principles) in 1722 which supplemented his work of four years earlier, Nouveau Système de musique theoretique (new system of music theory); these together may be considered the cornerstone of modern music theory relating to consonance and harmony. The Austrian composer Johann Fux published in 1725 his powerful treatise on the composition of counterpoint in the style of Palestrina under the title Gradus ad Parnassum (The Steps to Parnassus). He outlined various types of counterpoint (e.g., note against note), and suggested a careful application of the fourth so as to avoid dissonance.

Classical and romantic

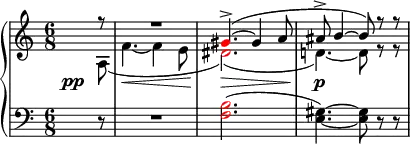

The blossoming of tonality and the establishment of well temperament in Bach's time both had a continuing influence up to the late romantic period, and the tendencies towards quartal harmony were somewhat suppressed. An increasingly refined cadence, and triadic harmony defined the musical work of this era. Counterpoint was simplified to favour an upper line with a clear accompanying harmony. Still, there are many examples of dense counterpoint utilizing fourths in this style, commonly as part of the background urging the harmonic expression in a passage along to a climax. Mozart in his so-called Dissonance Quartet KV 465 (![]() Listen) used chromatic and whole tone scales to outline fourths, and the subject of the fugue in the third movement of Beethoven's Piano sonata op. 110 (

Listen) used chromatic and whole tone scales to outline fourths, and the subject of the fugue in the third movement of Beethoven's Piano sonata op. 110 (![]() Listen) opens with three ascending fourths. These are all melodic examples, however, and the underlying harmony is built on thirds.

Listen) opens with three ascending fourths. These are all melodic examples, however, and the underlying harmony is built on thirds.

Composers started to reassess the quality of the fourth as a consonance rather than a dissonance. This would later influence the development of quartal and quintal harmony.

The Tristan chord is made up of the notes F♮, B♮, D♯ and G♯ and is the first chord heard in Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde.

The chord had been found in earlier works, notably Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 18, but Wagner's usage was significant, first because it is seen as moving away from traditional tonal harmony and even towards atonality, and second because with this chord Wagner actually provoked the sound or structure of musical harmony to become more predominant than its function, a notion which was soon after to be explored by Debussy and others.

Fourth-based harmony became important in the work of Slavic and Scandinavian composers such as Modest Mussorgsky, Leoš Janáček, and Jean Sibelius. These composers used this harmony in a pungent, uncovered, almost archaic way, often incorporating the folk music of their particular homelands. Sibelius' Piano Sonata in F-Major op. 12 of 1893 used tremolo passages of near-quartal harmony in a way that was relatively difficult and modern. Even in the example from Mussorgsky's piano-cycle Pictures at an Exhibition (Избушка на курьих ножках (Баба-Яга) – The Hut on Fowl's Legs) (![]() Listen) the fourth always makes an "unvarnished" entrance.

Listen) the fourth always makes an "unvarnished" entrance.

The romantic composers Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, had used the special "thinned out" sound of fourth-chord in late works for piano (Nuages gris (Grey Clouds), La lugubre gondola (The Mournful Gondola), and other works).

In the 1897 work The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'Apprenti sorcier) by Paul Dukas, the repetition of rising fourths is a musical representation of the tireless work of out-of-control walking brooms causes the water level in the house to "rise and rise". Quartal harmony in Ravel's Sonatine and Ma Mère l'Oye (Mother Goose) would follow a few years later.

Western classical music

In the 20th century, harmony explicitly built on fourths and fifths became important. This became known as quartal harmony for chords based on fourths and quintal harmony for chords based on fifths. In the music of composers of early 20th century France, fourth chords became consolidated with ninth chords, the whole tone scale, the pentatonic scale, and polytonality as part of their language, and quartal harmony became an important means of expression in music by Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and others. Examples are found in Debussy's orchestral work La Mer (The Sea) and in his piano works, in particular La cathédrale engloutie (The Sunken Cathedral) from his Préludes for piano, Pour les quartes (For Fourths) and Pour les arpéges composées (For Composite Arpeggios) from his Etudes.

Bartók's music, such as the String Quartet No. 2, often makes use of a three-note basic cell, a perfect fourth associated with an external (C, F, G♭) or internal (C, E, F) minor second, as a common intervallic source in place of triadic harmonies.[6] |

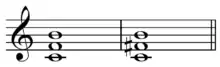

Quartal chord from Schoenberg's String Quartet No. 1 |

Jazz

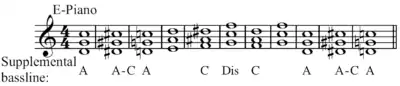

Jazz uses quartal harmonies (usually called voicing in fourths).

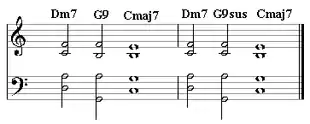

Cadences are often "altered" to include unresolved suspended chords which include a fourth above the bass:

|

|

References

- William Smith and Samuel Cheetham (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities. London: John Murray. ISBN 9780790582290.

- Sean Ferguson and Richard Parncutt. "Composing in the Flesh: Perceptually-Informed Harmonic Syntax" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-13. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Paul, Oscar (1885). A manual of harmony for use in music-schools and seminaries and for self-instruction, p.165. Theodore Baker, trans. G. Schirmer.

- William Drabkin (2001), "Fourth", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmilln Publishers).

- Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, seventh edition (Boston: McGraw-Hill): p. 37. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Robert P. Morgan (1991). Twentieth-Century Music: A History of Musical Style in Modern Europe and America, The Norton Introduction to Music History (New York: W. W. Norton), pp. 179–80. ISBN 978-0-393-95272-8.

- Morgan (1991), p. 71. "no doubt for its 'nontonal' quality"

- Floirat, Bernard (2015). "Introduction aux accords de quartes chez Arnold Schoenberg". p. 19 – via https://www.academia.edu/.

{{cite news}}: External link in|via=