K2

K2, at 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) above sea level, is the second-highest mountain on Earth, after Mount Everest at 8,849 metres (29,032 ft).[3] It lies in the Karakoram range, partially in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan-administered Kashmir and partially in the China-administered Trans-Karakoram Tract in the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang.[4][5][6][lower-alpha 1]

| K2 | |

|---|---|

K2 from Broad Peak Base Camp | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) Ranked 2nd |

| Prominence | 4,020 m (13,190 ft) Ranked 22nd |

| Isolation | 1,316 km (818 mi) |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 35°52′57″N 76°30′48″E[2] |

| Geography | |

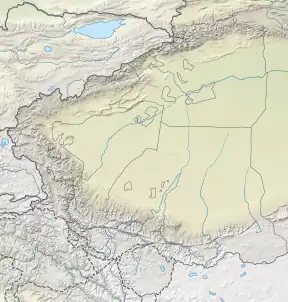

K2 Location of K2 relative to Xinjiang  K2 Location of K2 relative to Gilgit−Baltistan | |

| Countries |

|

| Parent range | Karakoram |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 31 July 1954 Achille Compagnoni & Lino Lacedelli |

| Easiest route | Abruzzi Spur |

K2 also became popularly known as the Savage Mountain after George Bell—a climber on the 1953 American expedition—told reporters, "It's a savage mountain that tries to kill you."[7] Of the five highest mountains in the world, K2 is the deadliest; approximately one person dies on the mountain for every four who reach the summit.[7][8] Also occasionally known as Mount Godwin-Austen,[9] other nicknames for K2 are The King of Mountains and The Mountaineers' Mountain,[10] as well as The Mountain of Mountains after prominent Italian climber Reinhold Messner titled his book about K2 the same.[11]

Although the summit of Everest is at a higher altitude, K2 is a more difficult and dangerous climb, due in part to its more northern location, where inclement weather is more common.[12] The summit was reached for the first time by the Italian climbers Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, on the 1954 Italian expedition led by Ardito Desio. As of February 2021, only 377 people have summited K2.[13] There have been 91 deaths during attempted climbs.

Most ascents are made during July and August, typically the warmest times of the year.[14] But in January 2021, K2 became the final eight-thousander to be summited in the winter; the mountaineering feat was accomplished by a team of Nepalese climbers, led by Nirmal Purja and Mingma Gyalje Sherpa.[15][16]

K2 has now been climbed by almost all of its ridges, but unlike other eight-thousanders, never from its eastern face.[17]

Name

The name K2 is derived from the notation used by the Great Trigonometrical Survey of British India. Thomas Montgomerie made the first survey of the Karakoram from Mount Haramukh, some 210 km (130 mi) to the south, and sketched the two most prominent peaks, labelling them K1 and K2, where the K stands for Karakoram.[18]

The policy of the Great Trigonometrical Survey was to use local names for mountains wherever possible[lower-alpha 2] and K1 was found to be known locally as Masherbrum. K2, however, appeared not to have acquired a local name, possibly due to its remoteness. The mountain is not visible from Askole, one of the highest settlements on the way to the mountain, nor from the nearest habitation to the north. K2 is only fleetingly glimpsed from the end of the Baltoro Glacier, beyond which few local people would have ventured.[19] The name Chogori, derived from two Balti words, chhogo ཆོ་གྷའོ་ ("big") and ri རི ("mountain") (چھوغوری)[20] has been suggested as a local name,[21] but evidence for its widespread use is scant. It may have been a compound name invented by Western explorers[22] or simply a bemused reply to the question "What's that called?"[19] It does, however, form the basis for the name Qogir (simplified Chinese: 乔戈里峰; traditional Chinese: 喬戈里峰; pinyin: Qiáogēlǐ Fēng) by which Chinese authorities officially refer to the peak. Other local names have been suggested including Lamba Pahar ("Tall Mountain" in Urdu) and Dapsang, but these are not widely used.[19]

With the mountain lacking a local name, the name Mount Godwin-Austen was suggested, in honour of Henry Godwin-Austen, an early explorer of the area. While the name was rejected by the Royal Geographical Society,[19] it was used on several maps and continues to be used occasionally.[23][24]

The surveyor's mark, K2, therefore continues to be the name by which the mountain is commonly known. It is now also used in the Balti language, rendered as Kechu or Ketu[22][25] (Balti: کے چو Urdu: کے ٹو). The Italian climber Fosco Maraini argued in his account of the ascent of Gasherbrum IV that while the name of K2 owes its origin to chance, its clipped, impersonal nature is highly appropriate for so remote and challenging a mountain. He concluded that it was:

... just the bare bones of a name, all rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human. It is atoms and stars. It has the nakedness of the world before the first man—or of the cindered planet after the last.[26]

André Weil named K3 surfaces in mathematics partly after the beauty of the mountain K2.[27]

Geographical setting

K2 lies in the northwestern Karakoram Range. It is located in the Baltistan region of Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, and the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang, China.[lower-alpha 1] The Tarim sedimentary basin borders the range on the north and the Lesser Himalayas on the south. Melt waters from glaciers, such as those south and east of K2, feed agriculture in the valleys and contribute significantly to the regional fresh-water supply.

K2 is ranked 22nd by topographic prominence, a measure of a mountain's independent stature. It is a part of the same extended area of uplift (including the Karakoram, the Tibetan Plateau, and the Himalayas) as Mount Everest, and it is possible to follow a path from K2 to Everest that goes no lower than 4,594 metres (15,072 ft), at the Kora La on the Nepal/China border in the Mustang Lo. Many other peaks far lower than K2 are more independent in this sense. It is, however, the most prominent peak within the Karakoram range.[2]

K2 is notable for its local relief as well as its total height. It stands over 3,000 metres (9,840 ft) above much of the glacial valley bottoms at its base. It is a consistently steep pyramid, dropping quickly in almost all directions. The north side is the steepest: there it rises over 3,200 metres (10,500 ft) above the K2 (Qogir) Glacier in only 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) of horizontal distance. In most directions, it achieves over 2,800 metres (9,200 ft) of vertical relief in less than 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[28]

A 1986 expedition led by George Wallerstein made an inaccurate measurement showing that K2 was taller than Mount Everest, and therefore the tallest mountain in the world.[29] A corrected measurement was made in 1987, but by then the claim that K2 was the tallest mountain in the world had already made it into many news reports and reference works.[30]

Height

K2's height given on maps and encyclopedias is 8,611 metres (28,251 ft). In the summer of 2014, a Pakistani-Italian expedition to K2, named "K2 60 Years Later", was organized to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of K2. One of the goals of the expedition was to accurately measure the height of the mountain using satellite navigation. The height of K2 measured during this expedition was 8,609.02 metres (28,244.8 ft).[31][32]

Geology

The mountains of K2 and Broad Peak, and the area westward to the lower reaches of Sarpo Laggo glacier, consist of metamorphic rocks, known as the K2 Gneiss, and part of the Karakoram Metamorphic Complex.[33][34] The K2 Gneiss consists of a mixture of orthogneiss and biotite-rich paragneiss. On the south and southeast face of K2, the orthogneiss consists of a mixture of a strongly foliated plagioclase-hornblende gneiss and a biotite-hornblende-K-feldspar orthogneiss, which has been intruded by garnet-mica leucogranitic dikes. In places, the paragneisses include clinopyroxene-hornblende-bearing psammites, garnet (grossular)-diopside marbles, and biotite-graphite phyllites. Near the memorial to the climbers who have died on K2, above Base Camp on the south spur, thin impure marbles with quartzites and mica schists, called the Gilkey-Puchoz sequence, are interbanded within the orthogneisses. On the west face of Broad Peak and the south spur of K2, lamprophyre dikes, which consist of clinopyroxene and biotite-porphyritic vogesites and minettes, have intruded the K2 gneiss. The K2 Gneiss is separated from the surrounding sedimentary and metasedimentary rocks of the surrounding Karakoram Metamorphic Complex by normal faults. For example, a fault separates the K2 gneiss of the east face of K2 from limestones and slates comprising nearby Skyang Kangri.[33][35]

40Ar/39Ar ages of 115 to 120 million years ago obtained from and geochemical analyses of the K2 Gneiss demonstrate that it is a metamorphosed, older, Cretaceous, pre-collisional granite. The granitic precursor (protolith) to the K2 Gneiss originated as the result of the production of large bodies of magma by a northward-dipping subduction zone along what was the continental margin of Asia at that time and their intrusion as batholiths into its lower continental crust. During the initial collision of the Asia and Indian plates, this granitic batholith was buried to depths of about 20 kilometres (12 mi) or more, highly metamorphosed, highly deformed, and partially remelted during the Eocene Period to form gneiss. Later, the K2 Gneiss was then intruded by leucogranite dikes and finally exhumed and uplifted along major breakback thrust faults during post-Miocene time. The K2 Gneiss was exposed as the entire K2-Broad Peak-Gasherbrum range experienced rapid uplift with which erosion rates have been unable to keep pace.[33][36]

Climbing history

Early attempts

The mountain was first surveyed by a British team in 1856. Team member Thomas Montgomerie designated the mountain "K2" for being the second peak of the Karakoram range. The other peaks were originally named K1, K3, K4, and K5, but were eventually renamed Masherbrum, Gasherbrum IV, Gasherbrum II, and Gasherbrum I, respectively.[37] In 1892, Martin Conway led a British expedition that reached "Concordia" on the Baltoro Glacier.[38]

The first serious attempt to climb K2 was undertaken in 1902 by Oscar Eckenstein, Aleister Crowley, Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Heinrich Pfannl, Victor Wessely, and Guy Knowles via the Northeast Ridge. In the early 1900s, modern transportation did not exist in the region: it took "fourteen days just to reach the foot of the mountain".[39] After five serious and costly attempts, the team reached 6,525 metres (21,407 ft)[40]—although considering the difficulty of the challenge, and the lack of modern climbing equipment or weatherproof fabrics, Crowley's statement that "neither man nor beast was injured" highlights the relative skill of the ascent. The failures were also attributed to sickness (Crowley was suffering the residual effects of malaria), a combination of questionable physical training, personality conflicts, and poor weather conditions—of 68 days spent on K2 (at the time, the record for the longest time spent at such an altitude) only eight provided clear weather.[41]

The next expedition to K2, in 1909, led by Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, reached an elevation of around 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the South East Spur, now known as the Abruzzi Spur (or Abruzzi Ridge). This would eventually become part of the standard route, but was abandoned at the time due to its steepness and difficulty. After trying and failing to find a feasible alternative route on the West Ridge or the North East Ridge, the Duke declared that K2 would never be climbed, and the team switched its attention to Chogolisa, where the Duke came within 150 metres (490 ft) of the summit before being driven back by a storm.[42]

The next attempt on K2 was not made until 1938, when the First American Karakoram expedition led by Charles Houston made a reconnaissance of the mountain. They concluded that the Abruzzi Spur was the most practical route and reached a height of around 8,000 meters (26,000 ft) before turning back due to diminishing supplies and the threat of bad weather.[43][44]

The following year, the 1939 American expedition led by Fritz Wiessner came within 200 metres (660 ft) of the summit but ended in disaster when Dudley Wolfe, Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, and Pintso disappeared high on the mountain.[45][46]

Charles Houston returned to K2 to lead the 1953 American expedition. The attempt failed after a storm pinned down the team for 10 days at 7,800 metres (25,590 ft), during which time climber Art Gilkey became critically ill. A desperate retreat followed, during which Pete Schoening saved almost the entire team during a mass fall (known simply as The Belay), and Gilkey was killed, either in an avalanche or in a deliberate attempt to avoid burdening his companions. Despite the retreat and tragic end, the expedition has been given iconic status in mountaineering history.[47][48][49] The Gilkey Memorial was built in his memory at the mountain's foot.[50]

Success and repeats

The 1954 Italian expedition finally succeeded in ascending to the summit of K2 via the Abruzzi Spur on 31 July 1954. The expedition was led by Ardito Desio, and the two climbers who reached the summit were Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni. The team included a Pakistani member, Colonel Muhammad Ata-ullah, who had been a part of the 1953 American expedition. Also on the expedition were Walter Bonatti and Pakistani Hunza porter Amir Mehdi, who both proved vital to the expedition's success in that they carried oxygen tanks to 8,100 metres (26,600 ft) for Lacedelli and Compagnoni. The ascent is controversial because Lacedelli and Compagnoni established their camp at a higher elevation than originally agreed with Mehdi and Bonatti. It being too dark to ascend or descend, Mehdi and Bonatti were forced to overnight without shelter above 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) leaving the oxygen tanks behind as requested when they descended. Bonatti and Mehdi survived, but Mehdi was hospitalised for months and had to have his toes amputated because of frostbite. Efforts in the 1950s to suppress these facts to protect Lacedelli and Compagnoni's reputations as Italian national heroes were later brought to light. It was also revealed that the moving of the camp was deliberate, a move apparently made because Compagnoni feared being outshone by the younger Bonatti. Bonatti was given the blame for Mehdi's hospitalisation.[51]

On 9 August 1977, 23 years after the Italian expedition, Ichiro Yoshizawa led the second successful ascent, with Ashraf Aman as the first native Pakistani climber. The Japanese expedition took the Abruzzi Spur and used more than 1,500 porters.[52]

The third ascent of K2 was in 1978, via a new route, the long and corniced Northeast Ridge. The top of the route traversed left across the East Face to avoid a vertical headwall and joined the uppermost part of the Abruzzi route. This ascent was made by an American team, led by James Whittaker; the summit party was Louis Reichardt, Jim Wickwire, John Roskelley, and Rick Ridgeway. Wickwire endured an overnight bivouac about 150 metres (490 ft) below the summit, one of the highest bivouacs in history. This ascent was emotional for the American team, as they saw themselves as completing a task that had been begun by the 1938 team forty years earlier.[53]

Another notable Japanese ascent was that of the difficult North Ridge on the Chinese side of the peak in 1982. A team from the Japan Mountaineering Association led by Isao Shinkai and Masatsugo Konishi put three members, Naoe Sakashita, Hiroshi Yoshino, and Yukihiro Yanagisawa, on the summit on 14 August. However Yanagisawa fell and died on the descent. Four other members of the team achieved the summit the next day.[54]

The first climber to reach the summit of K2 twice was Czech climber Josef Rakoncaj. Rakoncaj was a member of the 1983 Italian expedition led by Francesco Santon, which made the second successful ascent of the North Ridge (31 July 1983). Three years later, on 5 July 1986, he reached the summit via the Abruzzi Spur (double with Broad Peak West Face solo) as a member of Agostino da Polenza's international expedition.[55]

The first woman to summit K2 was Polish climber Wanda Rutkiewicz on 23 June 1986. Liliane and Maurice Barrard who had summited later that day, fell during the descent; Liliane Barrard's body was found on 19 July 1986 at the foot of the south face.[56]

In 1986, two Polish expeditions summited via two new routes, the Magic Line[57] and the Polish Line (Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski). Piotrowski fell to his death as the two were descending.

Thirteen climbers from several expeditions died in the 1986 K2 disaster. Another six mountaineers died in the 1995 K2 disaster, while eleven climbers died in the 2008 K2 disaster.[58][59]

Recent attempts

- 2004

- In 2004, the Spanish climber Carlos Soria Fontán became the oldest person ever to summit K2, at the age of 65.[60]

- 2008

- On 1 August 2008, a group of climbers went missing after a large piece of ice fell during an avalanche, taking out the fixed ropes on part of the route; four climbers were rescued, but 11, including Meherban Karim from Pakistan[61] and Ger McDonnell, the first Irish person to reach the summit, were confirmed dead.[62]

- 2009

- Despite several attempts, nobody reached the summit.

- 2010

- On 6 August 2010, Fredrik Ericsson, who intended to ski from the summit, joined Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner on the way to the summit of K2. Ericsson fell 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and was killed. Kaltenbrunner aborted her summit attempt.[63]

- Despite several attempts, nobody reached the summit.

- 2011

- On 23 August 2011, a team of four climbers reached the summit of K2 from the North side. Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner became the first woman to complete all 14 eight-thousanders without supplemental oxygen.[64] Kazakhs Maxut Zhumayev and Vassiliy Pivtsov completed their eight-thousanders quest. The fourth team member was Dariusz Załuski from Poland.[65]

- 2012

- The year started with a Russian team aiming for a first winter ascent. The expedition ended with the death of Vitaly Gorelik due to frostbite and pneumonia. The Russian team cancelled the ascent.[66] In the summer season, K2 saw a record crowd standing on its summit—28 climbers in a single day—bringing the total for the year to 30.[67]

- 2013

- On 28 July 2013, two New Zealanders, Marty Schmidt and his son Denali, died after an avalanche destroyed their camp. A guide had reached their camp, but said they were nowhere to be seen and the campsite tent showed signs of having been hit by an avalanche. British climber Adrian Hayes, who was with the group, later posted on his Facebook page that the campsite had been wiped out.[68]

- 2014

- On 26 July 2014, the first team of Pakistani climbers scaled K2. There were six Pakistani and three Italian climbers in the expedition, called K2 60 Years Later, according to BBC. Previously, K2 had only been summited by individual Pakistanis as part of international expeditions.[69] Another team, consisting of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita, Maya Sherpa, and Dawa Yangzum Sherpa, became the first Nepali women to climb K2.[70]

- On 27 July 2014, Garrett Madison led a team of three American climbers and six Sherpas to summit K2.[71][72]

- On 31 July 2014, Boyan Petrov completed the first Bulgarian ascent, just 8 days after climbing Broad Peak. Boyan is among the very few climbers with diabetes to climb above 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) without the use of supplemental oxygen.[73]

- 2017

- On 28 July 2017, Vanessa O'Brien led an international team of 12 with Mingma Gyalje Sherpa of Dreamers Destination to the summit of K2 and became the first British and American woman to summit K2, and the eldest woman to summit K2 at the age of 52 years old.[74] She paid tribute to Julie Tullis and Alison Hargreaves, two British women who summited K2, in 1986 and 1995 respectively, but died during their descents. Other notable summits included John Snorri Sigurjónsson and Dawa Gyalje Sherpa who joined his sister (Dawa Yangzum Sherpa), becoming the second set of siblings to summit K2.[75] Both Mingma Gyalje Sherpa and Fazal Ali recorded their second K2 summits.

- 2018

- On 22 July 2018, Garrett Madison became the first American climber to reach the summit of K2 more than once when he led an international team of eight climbers, nine Nepali Sherpas, four Pakistani high-altitude porters, and two other Madison Mountaineering guides to the summit.[76][77]

- On 22 July 2018, Polish mountaineer and mountain runner Andrzej Bargiel became the first person to ski down from summit to base camp.[78]

- 2019

- On 25 July 2019, Anja Blacha became the first German woman to summit K2. She climbed without the use of supplemental oxygen.[79]

- 2022

- On 22 July 2022 more than 100 summits on K2 in a single day were recorded. This is the highest number of summits in a single day ever on K2.[80]

Winter expeditions

- 1987/1988 — Polish-Canadian-British expedition led by Andrzej Zawada from the Pakistani side, consisting of 13 Poles, 7 Canadians and 4 Brits. 2 March Krzysztof Wielicki and Leszek Cichy established camp III at 7,300 metres (24,000 ft) above sea, followed by Roger Mear and Jean-Francois Gagnon few days later. Hurricane winds and frostbite forced the team to retreat.[81]

- 2002/2003 — Netia K2 Polish Winter Expedition. The team of fourteen climbers was led by Krzysztof Wielicki, and included four members from Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Georgia. They intended to climb North Ridge. Marcin Kaczkan, Piotr Morawski and Denis Urubko established camp IV at 7,650 metres (25,100 ft) above sea level. The final ascent started by Kaczkan and Urubko failed due to the destruction of the tent by harsh weather in camp IV and Kaczkan's cerebral edema.[81]

- 2011/2012 — Russian expedition. Nine Russian climbers attempted K2's Abruzzi Spur route. They managed to reach 7,200 metres (23,600 ft) above sea level (Vitaly Gorelik, Valery Shamalo and Nicholas Totmyanin), but had to retreat due to hurricane-force winds as well as frostbite on both of Gorelik's hands. After their descent to base camp and an unsuccessful call for Gorelik's evacuation (helicopter could not reach them through the worsening weather), the climber died of pneumonia and cardiac arrest. Following the incident, the expedition was called off.[81][82]

- 2017/2018 — Polish National Winter Expedition led by Krzysztof Wielicki, consisting of 13 climbers, started in the end of December 2017. The team initially attempted to summit via the south-southeastern spur (Cesen route), switching to the Abruzzi Spur after an injury on the previous route.[83][84][85][86] Via the Cesen/Basque route they reached up to 6,300 metres (20,700 ft), while on the Abruzzi Spur route they reached up to 7,400 metres (24,300 ft). However, Denis Urubko reported that during his solo attempt he probably reached up to 7,600 metres (24,900 ft).[87]

- 2021 — Ten climbers from an international expedition made the first winter summit on 16 January 2021. The group all summited together, and consisted of Mingma Gyalje Sherpa, Nirmal Purja, Gelje Sherpa, Mingma David Sherpa, Mingma Tenzi Sherpa, Dawa Temba Sherpa, Pem Chhiri Sherpa, Kilu Pemba Sherpa, Dawa Tenjing Sherpa, and Sona Sherpa. The summiting group consisted entirely of indigenous climbers from Nepal. Nirmal Purja was the only one who reached the summit without the use of supplemental oxygen. The summit temperature was −40 °C (−40 °F). On the same day Spanish team member Sergi Mingote died on the descent from Camp III; he fell somewhere between Camp I and Advanced Base Camp.[16][15][88][89][90][91][92][93][94] Other famous climbers who died on the same expedition include Atanas Skatov,[95][96][97] Ali Sadpara, John Snorri, and Juan Pablo Mohr Prieto.[98][99]

Climbing routes and difficulties

There are a number of routes on K2, of somewhat different character, but they all share some key difficulties, the first being the extremely high altitude and resulting lack of oxygen: there is only one-third as much oxygen available to a climber on the summit of K2 as there is at sea level.[100] The second is the propensity of the mountain to experience extreme storms of several days duration, which have resulted in many of the deaths on the peak. The third is the steep, exposed, and committing nature of all routes on the mountain, which makes retreat more difficult, especially during a storm. Despite many attempts the first successful winter ascents occurred only in 2021. All major climbing routes lie on the Pakistani side. The base camp is also located on the Pakistani side.[101]

Abruzzi Spur

The standard route of ascent, used by 75% of all climbers, is the Abruzzi Spur,[102][103] located on the Pakistani side, first attempted by Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi in 1909. This is the peak's southeast ridge, rising above the Godwin-Austen Glacier. The spur proper begins at an altitude of 5,400 metres (17,700 ft), where Advanced Base Camp is usually placed. The route follows an alternating series of rock ribs, snow/ice fields, and some technical rock climbing on two famous features, "House's Chimney" and the "Black Pyramid." Above the Black Pyramid, dangerously exposed and difficult-to-navigate slopes lead to the easily visible "Shoulder", and thence to the summit. The last major obstacle is a narrow couloir known as the "Bottleneck", which places climbers dangerously close to a wall of seracs that form an ice cliff to the east of the summit. It was partly due to the collapse of one of these seracs around 2001 that no climbers reached the summit in 2002 and 2003.[104]

Between 1 - 2 August 2008, 11 climbers from several expeditions died during a series of accidents, including several ice falls in the Bottleneck.[62][105]

North Ridge

Almost opposite the Abruzzi Spur is the North Ridge,[102][103] which ascends the Chinese side of the peak. It is rarely climbed, partly due to very difficult access, involving crossing the Shaksgam River, which is a hazardous undertaking.[106] In contrast to the crowds of climbers and trekkers at the Abruzzi basecamp, usually at most two teams are encamped below the North Ridge. This route, more technically difficult than the Abruzzi, ascends a long, steep, primarily rock ridge to high on the mountain—Camp IV, the "Eagle's Nest" at 7,900 metres (25,900 ft)—and then crosses a dangerously slide-prone hanging glacier by a leftward climbing traverse, to reach a snow couloir which accesses the summit.

Besides the original Japanese ascent, a notable ascent of the North Ridge was the one in 1990 by Greg Child, Greg Mortimer, and Steve Swenson, which was done alpine style above Camp 2, though using some fixed ropes already put in place by a Japanese team.[106]

Other routes

Because 75% of people who climb K2 use the Abruzzi Spur, these listed routes are rarely climbed. No one has climbed the East Face of the mountain due to the instability of the snow and ice formations on that side.[107] Besides the East Face, the North Face has not yet been climbed either. In 2007 Denis Urubko and Serguey Samoilov intended to climb the K2's North Face but they were stymied by increasingly deteriorating conditions. After finding their intended route menaced by growing avalanche danger, they traversed onto the normal North Ridge route and summited on 2 October 2007, making the latest summer season ascent of the peak in history.[108]

- Northeast Ridge

- Long and corniced, finishes on uppermost part of Abruzzi route. Ridge first crossed by a Polish expedition led by Janusz Kurczab in 1976. The team was not able to summit due to poor weather.[109] First climbed by Louis Reichardt and James Wickwire on 6 September 1978.[110]

- West Ridge

- First climbed in 1981 by a Japanese team.[111] This route starts on the distant Negrotto Glacier and goes through unpredictable bands of rock and snowfields.

- Southwest Pillar or "Magic Line"

- Very technical, and the second most demanding. First climbed in 1986 by the Polish-Slovak trio Piasecki-Wróż-Božik. Since then Jordi Corominas from Spain has been the only successful climber on this route (he summited in 2004),[112] despite many other attempts.

- South Face or "Polish Line" or "Central Rib"

- Extremely exposed, demanding, and dangerous. In July 1986, Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski summited on this route. Piotrowski was killed while descending on the Abruzzi Spur. The route starts off the first part of the Southwest Pillar, and then deviates into a totally exposed, snow-covered cliff area, then through a gully known as "The Hockey Stick", and then goes up to yet another exposed cliff-face, and the route continues through yet another extremely exposed section all the way up to the point where the route joins with the Abruzzi Spur about 300 m (1,000 ft) before the summit. Reinhold Messner called it a suicidal route and so far, no one has repeated Kukuczka and Piotrowski's achievement. "The route is so avalanche-prone, that no one else has ever considered a new attempt."[113][114]

- Northwest Face

- First ascent via this route was in 1990 by a Japanese team; this route is located on the Chinese side of the mountain. This route is known for its chaotic rock and snowfields all the way up to the summit.[112]

- Northwest Ridge

- First climbed in 1991 by a French team: Pierre Beghin and Christophe Profit. Finishes on North Ridge. The second attempt in 1995 by an American team, they reached 8100 metres the 2 August before turning back in deteriorating weather.[115]

- South-southeast spur or "Cesen route" or "Basque route"

- It runs the pillar between the Abruzzi Spur and the Polish Route. It connects with the Abruzzi Spur on the Shoulder, above the Black Pyramid and below the Bottleneck; since it avoids the Black Pyramid, it is considered safer. In 1986, Tomo Česen ascended to 8,000 m (26,000 ft) via this route. The first summit via this route was by a Basque team in 1994.[112]

Use of supplemental oxygen

For most of its climbing history, K2 was not usually climbed with supplemental oxygen, and small, relatively lightweight teams were the norm.[102][103] However, the 2004 season saw a great increase in the use of oxygen: 28 of 47 summiteers used oxygen in that year.[104]

Acclimatisation is essential when climbing without oxygen to avoid some degree of altitude sickness.[117] K2's summit is well above the altitude at which high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), or high altitude cerebral edema (HACE) can occur.[118] In mountaineering, when ascending above an altitude of 8,000 metres (26,000 ft), the climber enters what is known as the death zone.[119]

Films

- K2 (1991), an adventure drama film adaption of Patrick Meyers' original stage play, directed by Franc Roddam and loosely based on the story of Jim Wickwire and Louis Reichardt, the first Americans to summit K2

- Vertical Limit (2000), an American survival thriller film directed by Martin Campbell

- K2: Siren of the Himalayas (2012), an American documentary film directed by Dave Ohlson, that follows a group of climbers during their 2009 attempt to summit K2 on the 100-year anniversary of the Duke of Abruzzi’s landmark K2 expedition in 1909

- The Summit (2012), a documentary film about the 2008 K2 disaster, directed by Nick Ryan

- K2: The Impossible Descent (2020), a documentary film about Polish ski mountaineer Andrzej Bargiel's 2018 K2 climb and descent on skis, directed by Sławomir Batyra and Steven Robillard

Disasters

Passes

Windy Gap is a 6,111-meter (20,049 ft)-high mountain pass 35.87318°N 76.57692°E at east of K2, north of Broad Peak, and south of Skyang Kangri.

See also

- List of books about K2

- Concordia

- Gilgit–Baltistan

- The Himalayan Database

- Kangchenjunga (3rd highest after Everest and K2)

- List of deaths on eight-thousanders

- List of highest mountains

- List of Mount Everest death statistics

- List of mountains in Pakistan

- List of peaks by prominence

- List of people who died climbing Mount Everest

- List of tallest mountains in the Solar System

- Mount Hood climbing accidents

- Trans-Karakoram Tract

Notes

- K2 is located in Gilgit–Baltistan, a region, which along with Azad Kashmir, forms Pakistan administered Kashmir. The Kashmir region is currently the centre of a territorial dispute between Pakistan and India. India maintains a territorial dispute on Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Likewise, Pakistan maintains a territorial dispute on Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian-administered part of the region.

- The most obvious exception to this policy was Mount Everest, where the Tibetan name Chomolungma (Qomolongma) was probably known, but ignored in order to pay tribute to George Everest. See Curran, pp. 29–30

References

- "K2". Peakbagger.com.

- "Karakoram and India/Pakistan Himalayas Ultra-Prominences". peaklist.org. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "Mount Everest is two feet taller, China and Nepal announce". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "K2". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 18 November 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2021. Quote: "K2 is located in the Karakoram Range and lies partly in a Chinese-administered enclave of the Kashmir region within the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang, China, and partly in the Gilgit-Baltistan portion of Kashmir under the administration of Pakistan."

- Jan·Osma鈔czyk, Edmund; Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003), "Jammu and Kashmir", Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Taylor & Francis, pp. 1189–, ISBN 978-0-415-93922-5 Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute between India and Pakistan. It has borders with Pakistan and China."

- "Kashmir", Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2006, p. 328, ISBN 978-0-7172-0139-6,

KASHMIR, kash'mer, the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, administered partly by India, partly by Pakistan, and partly by China. The region has been the subject of a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan since they became independent in 1947

- Stone, Larry (6 September 2018). "Summiting 'Savage Mountain': The harrowing story of these Washington climbers' K2 ascent". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "AdventureStats – by Explorersweb". adventurestats.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Chhoghori, K2. "K2 Chhoghori The King of Karakoram". Skardu.pk. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Leger, C. J. (8 February 2017). "K2: The King of Mountains". Base Camp Magazine. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Messner, Reinhold. "K2: Mountain of Mountains". Goodreads. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "EXPLAINER: K2's peak beckons the daring, but climbers rarely answer call in winter". 10 February 2021.

- "Why the 'savage' K2 peak beckons the daring, but rarely in winter". Aljazeera. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Brummit, Chris (16 December 2011). "Russian team to try winter climb of world's 2nd-highest peak". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Nepali mountaineers achieve historic winter first on K2". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Winter K2 Update: FIRST WINTER K2 SUMMIT!!!!". alanarnette.com. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- "Asia, Pakistan, K2 Attempt". The American Alpine Club. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Curran, p. 25

- Curran, p. 30

- "Convert Roman into Urdu Script". changathi.com.

- "Place names – II". The Express Tribune. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- Carter, H. Adams (1983). "A Note on the Chinese Name for K2, "Qogir"". Notes. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 25 (57): 296. Retrieved 6 November 2016. Carter, the long-time editor of the AAJ, goes on to say that the name Chogori "has no local usage. The mountain was not prominently visible from places where local inhabitants ventured and so had no local name ... The Baltis use no other name for the peak than K2, which they pronounce 'Ketu'. I strongly recommend against the use of the name Chogori in any of its forms."

- Pakistan. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

-

Carter, H. Adams (1975). "Balti Place Names in the Karakoram". Feature Article. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 20 (1): 52–53. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

Godwin Austen is the name of the glacier at its eastern foot and is only incorrectly used on some maps as the name of the mountain.

- Carter, op cit. Carter notes a generalisation of the word Ketu: "A new word, ketu, meaning 'big peak', seems to be entering the Balti language."

- Maraini, Fosco (1961). Karakoram: the ascent of Gasherbrum IV. Hutchinson. Quoted in Curran, p. 31.

- Zaldivar, Felipe (19 September 2017). "Lectures on K3 Surfaces [review]". MAA Reviews. Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Wala, Jerzy (1994). "The Eight-Thousand-Metre Peaks of the Karakoram". Orographical Sketch Map. The Climbing Company Ltd/Cordee.

- "How High Is Everest? Climbers Seek Answer". The New York Times. 18 May 1987.

- Ian (20 January 2000). "Which is taller, Mt. Everest or K2?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Lehmuller, Katherine; Mozzon, Marco. "Second to none". The Global Magazine of Leica Geosystems. Vol. Reporter 72. pp. 40–42.

- How High Really Is K2? (PDF), 2014, retrieved 7 May 2021

- Searle, M.P. (1991). Geology and Tectonics of the Karakoram Mountains. New York City: John Wiley & Sons. p. 358. ISBN 978-0471927730.

- Searle, M.P. (1991). Geological Map of the Central Karakoram Mountains. scale 1: 250,000. New York City: John Wiley & Sons.

- Searle, M.P.; R.R. Parrish; R. Tirrul; D.C. Rex (1990). "Age of crystallisation and cooling of the K2 gneiss in the Baltoro Karakoram". Journal of the Geological Society. London. 147 (4): 603–606. Bibcode:1990JGSoc.147..603S. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.147.4.0603. S2CID 129956294.

- Searle, M.P.; R.R. Parrish; A. Thow A; S.R. Noble; R. Phillips; D. Waters (2010). "Anatomy, Age and Evolution of a Collisional Mountain Belt: the Baltoro granite batholith and Karakroam Metamorphic Complex, Pakistani Karakoram". Journal of the Geological Society. London. 167 (1): 183–202. Bibcode:2010JGSoc.167..183S. doi:10.1144/0016-76492009-043. S2CID 130887875.

- Kenneth Mason (1987 edition) Abode of Snow p.346

- Houston, Charles S. (1953). K2, the Savage Mountain.McGraw-Hill.

- Crowley, Aleister (1989). "Chapter 16". The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. London: Arkana. ISBN 978-0-14-019189-9.

- "A timeline of human activity on K2". k2climb.net. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Booth, pp. 152–157 in chapter "Rhythms of Rapture"

- Curran, pp. 65–72

- Houston, Charles S; Bates, Robert (1939). Five Miles High (2000 Reprint by First Lyon Press, with introduction by Jim Wickwire ed.). Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-1-58574-051-2.

- Curran, pp.73–80

- Kaufman, Andrew J.; Putnam, William L. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-323-9.

- Curran pp. 81–94

- Houston, Charles S; Bates, Robert (1954). K2 – The Savage Mountain (2000 Reprint by First Lyon Press with introduction by Jim Wickwire ed.). Mc-Graw-Hill Book Company Inc. ISBN 978-1-58574-013-0.

- McDonald, pp. 119–140

- Curran, pp. 95–103

- O'Brien, Vanessa (30 August 2016). "Remembering Those Lost on the Savage Mountain". Adventure Journal.

- "Amir Mehdi: Left out to freeze on K2 and forgotten". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Curran, Appendix I

- Reichardt, Louis F. (1979). "K2: The End of a 40-Year American Quest". Feature Article. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 22 (1): 1–18. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "K2, North Ridge". American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 25 (57): 295. 1983. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Rakoncaj, Josef (1987). "Broad Peak and K2". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 29 (61): 274. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "K2, Women's Ascents and Tragedy". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 29 (61): 273. 1987. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Majer, Janusz (1987). "K2's Magic Line". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 29 (61): 10. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Haider, Kamran (3 August 2008). "Rescuers reach Italian after 11 die on K2". Reuters. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Ramesh, Randeep; South, Asia c. (5 August 2008). "K2 Tragedy: Death Toll on World's most Treacherous Mountain Reaches 11: Ice Sheet Collapse may have Triggered Events that Led to Climbing Disaster". The Guardian – via ProQuest.

- "Dozens Reach Top of K2". climbing.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- Kamran (20 December 2020). "Karim The Dream". Kamran On Bike. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Climber: 11 killed after avalanche on Pakistan's K2". CNN. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- "Österreicherin bricht nach Tod ihres Gefährten Besteigung von K2 ab" [Austrian cancels ascent of K2 after death of her companion]. Stern (in German). Archived from the original on 20 August 2010.

- "K2 editorial: end of an era in women's Himalaya". Explorers Web. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "K2 north pillar summiteers safely back!". Explorers Web. 25 August 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "K2: details on the fight for Vitaly Gorelik". Explorers Web. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "K2 summit pics and video: Polish climbers on a roll". Explorers Web. 3 August 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "New Zealand mountaineer and son feared dead on K2". The Guardian. 30 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "First Pakistan team of climbers scale K2 summit". BBC. 26 July 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Parker, Chris (29 July 2014). "First All-Female Nepalese Team Summits K2". Rock & Ice.

- "Everest Isn't the Only Mountain that Matters". Outside Online. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Dispatches: K2 2014". Madison Mountaineering. 2014.

- "With Diabetes to the Top". Diabetes:M. 23 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Staff Reporter (16 August 2017). "Vanessa thanks Pakistan govt for help in scaling K-2". The Nation. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Pokhrel, Rajan. "Vanessa O'Brien, John Snorri set record as 12 scale Mt K2". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "K2 2018 Summer Coverage: Record Weekend on K2 and a Death". The Blog on alanarnette.com. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "K2 2018 Archives". Madison Mountaineering.

- "First Ski descent on K2". dreamwanderlust.com. 22 July 2018.

- "K2 summiteer Anja Blacha: "More flexible on the mountain without breathing mask"". Adventure Mountain. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "K2 Expedition 2022 : List of climbers summited K2 in 2022". baltistantimes.com. 22 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- "History of Winter Climbing K2". altitudepakistan.blogspot.com. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Vitaly Gorelik Dies On K2 - Alpinist.com". www.alpinist.com. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Climbers Set Off to Be First to Summit World's Most Notorious Mountain in Winter". nationalgeographic.com. 29 December 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Polish Heading to K2 for First Winter Ascent Attempt". Gripped Magazine. 29 December 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Poland's 'ice warriors' risk life and limb to be first to summit K2 in winter". scmp.com. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "| CAMP". Camp.it. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "K2 remains notoriously savage during winter". dreamwanderlust.com. 6 March 2018.

- "All-Nepali winter first on K2".

- Parsain, Sangam (17 January 2021). "Mission possible: Ten Nepalis become first to climb Mt K2 in the dead of winter". The Kathmandu Post. The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Nepali climbers script history scaling K2 in winter season". No. 16 January 2021. The Himalayan Times. The Himalayan Times. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Geiger, Stephanie. "Aufstieg bei minus 40 Grad: Nepalesische Bergsteiger erreichen erstmals im Winter den Gipfel des K2". FAZ.NET (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- Sangam Prasain (19 January 2021). "My body was freezing. I told my teammates I couldn't move". kathmandupost.com. The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Nirmal Purja (18 January 2021). "Update 11 – With or without O2 ?". www.nimsdai.com. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Winter K2 Update: Oxygen Update. Next Chapter in Winter K2". alanarnette.com. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- "Bulgarian alpinist Skatov dies during K2 expedition". The Nation. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "Bulgarian Climber Dies On K2 Expedition". International Business Times. AFP News. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "Bulgarian climber dies during expedition on Pakistan's K2". The Express Tribune. AFP. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "K2: The Fallen Five". explorersweb.com. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- "Sadpara, Snorri and Mohr Missing on K2; Rescue Mission Temporarily Suspended". ukclimbing.com. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- "Altitude oxygen calculator". altitude.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Watson, Peter (12 January 2021). "Trekking to K2 base camp in Pakistan: everything you need to know". Lonely Planet.

- Fanshawe, Andy; Venables, Stephen (1995). Himalaya Alpine-Style. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-64931-3.

- Salkeld, Audrey, ed. (1998). World Mountaineering. Bulfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-2502-2.

- "Asia, Pakistan, Karakoram, Baltoro Muztagh, K2, Various Ascents and Records in the Anniversary Year". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 47 (79): 351–353. 2005. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Nine feared dead in K2 avalanche". BBC. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- Swenson, Steven J. (1991). "K2—The North Ridge". American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 33 (65): 19–32. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Winter 8000'ers Update: Gale on Manaslu, East Face of K2 "Impossible"". 28 January 2019.

- Bauer, Luke (4 October 2007). "Kazakhs Make Latest Season Ascent of K2 in History". Alpinist. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Kurczab, Janusz (1979). Soli S. Mehta (ed.). "Polish K2 Expedition – 1976". The Himalayan Journal. The Himalayan Club. 35. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "40 Years Later: The Story Behind the First American Ascent of K2". 18 October 2018.

- Matsuura, Teruo (1992). "K2's West Face". American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 34 (66): 83–87. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Leger, CJ (9 June 2017). "Routes Up to K2's Summit". Base Camp Magazine.

- Messner, R.; Gogna, A.; Salked, A. (1982). K2 Mountain of Mountains (in German). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-520253-8.

- "The Route – Climbers guide to K2". www.k2climb.net. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "AAC Publications – Asia, Pakistan, K2, Northwest Ridge Attempt".

- "K2 West Face direct". russianclimb.com. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

-

Muza, SR; Fulco, CS; Cymerman, A. (2004). "Altitude Acclimatisation Guide". U.S. Army Research Inst. Of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report (USARIEM–TN–04–05). Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Cymerman, A.; Rock, PB. "Medical Problems in High Mountain Environments. A Handbook for Medical Officers". US Army Research Inst. Of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report. USARIEM-TN94-2. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Woodward, Aylin. "What happens to your body in Mount Everest's 'death zone,' where 11 people have died in the past week". Business Insider. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

Bibliography

- Booth, Martin (2001) [2000]. A Magick Life: A Biography of Aleister Crowley (trade paperback) (Coronet ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-71806-4.

- Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-66007-2.

- McDonald, Bernadette (2007). Brotherhood of the Rope – The Biography of Charles Houston. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-942-2.

External links

- Himalaya-Info.org page on K2 (German)

- The climbing history of K2 from the first attempt in 1902 until the Italian success in 1954.

- "Sample of K2 poster product including Routes and Notes" (PDF). (235 KB) From Everest-K2 Posters

- "K2". SummitPost.org.

- K2 on GeoFinder.ch

- Map of K2

- List of ascents to December 2007

- 'K2: The Killing Peak' Men's Journal November 2008 feature

- Achille Compagnoni —Daily Telegraph obituary

- Dr Charles Houston —Daily Telegraph obituary

- k2climb.net