Kalapodi

Kalapodi (Greek: Καλαπόδι) is a modern Greek village in the Lokroi municipality, Phthiotis, Central Greece.[1] Lokroi straddles the pass leading over the low mountains between the Bay of Atalantis in the Gulf of Euboea to the plains of Boeotia north of Lake Copais. The road is often termed the Atalanti-Livadeia. The community of Atalanti, the chief deme of Lokroi, overlooks the Bay of Atalantis, while Livadeia is the current capital of Voiotia.

Kalapodi

Καλαπόδι | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view | |

Kalapodi | |

| Coordinates: 38°38′3″N 22°53′6″E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Geographic region | Central Greece |

| Municipality | Lokroi |

| City established | 2011 |

| Elevation | 328 m (1,076 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 751 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

Geography

Kalapodi is situated on the flank of the pass at the top in rolling upland. Mount Parnassus is visible to the southeast. On the west is Karagkiozis-Asprogies Wildlife Refuge, and on the west at a further distance Svarnias Wildlife Refuge, both mountainous. A subsidiary road connects Zeli, a mountain village, part of Kalapodi, on the north.

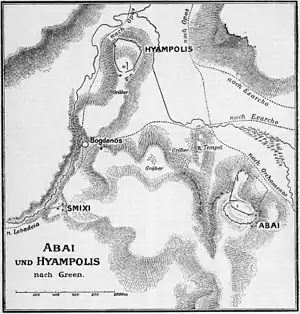

The pass is sometimes called in English "the Valley of Kalapodi." On the east, just before the village, it branches to another pass, "the Valley of Exarchos," named after the municipality of Exarchus, on its eastern flank.[2]: 523 Exarchus is of the same magnitude as Kalapodi, but a little larger. The road through the valley is the Atalanti-Orchomenus, which turns more sharply to the south to enter the plains of Boeotia more to the east, closer to the old capital of Thebes. Its starting point on the Atalanti-Livadeia road is and always has been a strategic intersection.

Kalapodi supports a population of several hundred persons, a few churches, a doctor, clinic, police station, kindergarten, primary school and facilities for travellers and tourists. Apart from these facilities the economic context is primarily agricultural.[3]

In ancient times the crossroads were the geopolitical center of the classical city-state of Phocis. The state was formed there at Hyampolis under the auspices of Artemis. It remained the capital. In the vicinity also was Abae, the seat of an oracle of Apollo. It was easily accessed from the north. Delphi was blocked on the north by Mount Parnassus.[4]

Locating ancient Abae

The name Kalapodi also denotes an archaeological site ca. 1 km east of the village, where an ancient sanctuary was discovered. The first temple there seems to have begun in the late Bronze Age, although habitation and possibly cult activity may have begun in the Middle Bronze Age. Successive temples continued without break through the Dark Age into the historical period. The last attested use phase of the sanctuary dates to Imperial Roman times.

There has been considerable difficulty in matching the archaeology with proto-historical places known to have been in the area: Hyampolis and Abae. After recent excavations the German Archaeological Institute in Athens has ventured to identify the site as that of Abae, the oracular sanctuary of Apollo.[4]

The locations of Hyampolis and Abae, although well-known to the ancient world, were lost to the modern. Kalapodi and Exarchus are of mediaeval provenance. It was perhaps during these centuries that the entire crossroads region was designated "Kalapodi." Locating the two ancient sites has been a process of slow discovery. The views currently available are based on the three periods of archaeological investigation up to 2020. The literature, photographs, and signs at the sites might reflect any of the three.

The British School's earliest view

In 1894 the British School at Athens, then in its infancy, undertook the first modern excavations in the region.[5] There were only two locations that could be major ancient sites, both in the Valley of Exarchos, then known as Kalapodi, bracketing the village to the north and south. These were located on Bogdanos (now Rigkouneika) Hill to the north and Kastro Hill to the south.[6] The road passes through the village and beside the hills.

The British examined both hills superficially, finding a wall on Kastro as well as remains of two temples. They had no evidence of the ancient identities but they were looking for two sites and these hills seemed the best candidates, so they labeled the southern one "the town of Abae" and the northern one "Hyampolis."[7] Neither one today is in Kalapodi, as Exarchus is an independent municipality within Lokroi, as is Kalapodi. The traditional names, however, often persist. Of the supposed town of Abae, the British Sckool reports that the excavation "was conducted in bad weather and proved disappointing."[5]

How much this assessment contributed to the site's subsequent neglect cannot be known, but no further work was done for 80 years. The reference works portrayed the geopolitics as the British had concluded; in particular, Pauly-Wissova, the major German encyclopedia, took up the theme.

The German Archaeological Institute’s earliest view

In 1970, R. Felsch of the DAI (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) visiting Kalapodi perused the site of a temple on a hillside beside the road between the village and the crossroads. It had been visited before with no great note. This time he believed there was more to be seen below the surface. He directed the excavation of the site by the DAI, 1973-1982.

The ruins turned out to be of two nearly contiguous temples parallel to each other and to the road.[8] They were termed “the north temple” and “the south temple.” These terms are not to be confused with the northern and southern hills around Exarchus. These nouns in the singular turned out to be somewhat inaccurate. Both north and south locations were raised on the ruins of multiple layers, which were named and numbered by temple: North Temple 1, 2, etc.

The functions of the temples were not so easily divided. They extended back into the Bronze Age, but sometimes there was only the north temple, at other times only the south, and for much of the time they stood together. Nevertheless the DAI suggests that the north temple was of Apollo; the south, of his twin, Artemis.

It was clear from the antiquity and continuity of the site that it was a third major candidate for historically famous locations around the crossroads. There were now three sites, two locations. Felsch created a third location by separating the Sanctuary of Artemis Elaphebolos from the city she patronized, Hyampolis. According to protohistory, after a rebellion against Thessaly and other non-Phocian states, Phocis created itself as a new state with capital at Hyampolis under the auspices of Artemis Elaphebolos, given her own shrine there. Delphi though nominally Phocian, was in the political hands of an amphictyony, or committee, formed from members of other states. Not so with either Abae or the sanctuary of Artemis.

Felsch redistributed locations to sites. Paliochori could not be Abae, as the sources had said it was unfortified, and Paliochori was not unfortified. The system seemed to work if Abae and Hyampolis were switched. Paliochori was now Hyampolis and Bogdanou Abae.[2] The only remaining slot was Kalapodi, which must be the temple complex of Artemis. There was a major loose end: Hyampolis was over 8 miles from the shrine of its guardian deity. Nevertheless this scheme was the one promulgated at the time.

Onlookers attempted to remedy the discrepancy by making Kalapodi into Hyampolis.[9] With the elucidation of this view in mind, the DAI supported a geophysical survey, 2014-2017, by the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. They found a grid representing a settlement but chronological probing revealed that different features were from different periods. It is not a single simultaneous fortified city, Hyampolis, which must remain for the present at Paliochori. Instead, it is considered the settlement supporting the sanctuary complex.[10]

Finds from the site are published in a monograph series edited by the German Archaeological Institute; so far, two volumes have appeared, covering ceramic and metal finds from the sanctuary.[11] These are compendia of articles by the participating archaeologists covering the many thousands of artifacts discovered.

The German Archaeological Institute’s latest view

Felsch had concentrated on the north temple, bringing it down to bedrock. He admitted it was dedicated to Apollo, but only as one of a pair, Apollo and Artemis. A fellow archaeologist, W-D. Niemeier, was troubled by another loose end: inscriptional mentions of Apollo were found only in the Valley of Kalapodi, while mentions of Artemis were only in the Valley of Exarchus, just the opposite of what one might expect if Felsch’s identification were true. One more switch of locations was required to mitigate the discrepancy: if the Temple of Artemis Elaphebolus were assigned to Bogdanou, and its then resident, Abae, were assigned to Kalapodi, then Artemis Elaphebolus could reside not far from her city, Hyampolis. Kastro may well have been only the acropolis of a larger city that covered much of the territory of Exarchus.

Felsch had already taken a stand and was involved in defending it by publishing the work on Kalapodi. Niemeier had reason to think Kalapodi was a better candidate for Abae. Much excavation remained to be done on the south temple. Believing that further evidence was to be found there, Niemeier referred to it as the source of a solution to ‘’Das Orakel-Rätsel’’, “the oracle riddle;” that is, where was the famous and ancient oracle, down in the Valley of Exarchus between Hyampolis and its distant shrine of Artemis, or up at the crossroads for all to encounter coming from the east, west, and south? The necessity for investigation was so great that Niemeier was able to acquire funding for it and was made director of the excavation by the DAI, 2004-2013.[10] The polarization of views between Felsch and Niemeier in the rest of the archaeological world for those years was more intense.

As the excavation proceeded the evidence began to preponderate that the site was Abae. A pedestal from a church nearby (Church of the Dormition of the Virgin) dedicated the now missing statue to the emperor Constantine. It was given in the name of the people of Abae.[12] It was also clear that the major temple, the northern, was of Apollo, not Artemis. Furthermore, Artemis only assumed her state-protection status after the institution of the state in the proto-historic period. Kalapodi, however, went back to the Late Bronze Age.

Currently the predominant view is that Kalapodi was in ancient times Abae. This change of view is not considered to change the impact of Felsch’s work, as he mainly catalogued and analyzed what was actually found under any name. Similarly, the British School is not to be faulted for failure of a correct identification with the resources they had at that time. Archaeology is simply not an infallible method.

References

- "Kalapodi, Greece Page". Falling Rain Software. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Donnellan, Lieve (2019). "Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier. Das Orakelheiligtum des Apollon von Abai/Kalapodi. Eines der bedeutendsten griechischen Heiligtümer nach den Ergebnissen der neuen Ausgrabungen (Book Reviews: multiperiod)". Journal of Greek Archaeology. 4. doi:10.32028/jga.v4i.515. S2CID 253863926.

- "Η ΕΛΑΦΗΒΟΛΟΣ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΣ" (in Greek). Society of the friends of Kalapodi's cultural heritage (Σύλλογος Φίλων Πολιτιστικής Κληρονομίας Καλαποδίου Φθιοτίδος). Archived from the original on 2011-08-08.

- McInerney, Jeremy (2011). "Delphi and Phokis : a Network Theory Approach". Pallas. 87 (87): 95–106. doi:10.4000/pallas.1948.

- "Digging I: the Earliest 19th-century BSA Excavations in the BSA SPHS Image Collection". Stories and News. British School at Athens. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Alternative names are Kastro Bogdanou and Kastro Paliochori. Kastro, from Latin castra, simply means "fort," which might apply to any hill with any ancient ruins on it. Sanchez-Moreno, Eduardo (2013). "Communication Routes in and around Epicnemidian Locris". In Pascual, José; Papakonstantinou, Maria-Foteini (eds.). Topography and History of Ancient Epicnemidian Locris. Leiden; Boston: Brill. p. 335.

- "PHOCIS.- Abae.-". American Journal of Archaeology. I: 352. 1897.

- Felsch’s plan of the temples is repeated in Hunt, Gloria R. (2006). Foundation Rituals and the Culture of Building in Ancient Greece (PDF) (PhD). University of North Carolina. p. 271.

- As an example of this point of view as late as 2017 refer to Department of Classics and Ancient History (2017). "Temple of Artemis". University of Warwick.. Their temple of Artemis is the site at Kalapodi, while Hyampolis was supposed to have become Kalapodi itself, thus bringing Hyampolis and its goddess to the same location. Abae on the other hand was 8 km away, exactly the distance to Bogdanou. Paliochori is left as a loose end.

- "Kalapodi" (in German and English). DAI. 2016.

- The two volumes: Felsch, Rainer C.S., ed. (1996). Kalapodi: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen im Heiligtum der Artemis und des Apollon von Hyampolis in der antiken Phokis. Vol. I. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. and Felsch, Rainer C.S., ed. (2007). Kalapodi: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen im Heiligtum der Artemis und des Apollon von Hyampolis in der antiken Phokis. Vol. II. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern.

- Morgan, Catherine (December 2009). "Kalapodi – 2007". BCH and BSA.

External links

![]() Media related to Kalapodi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kalapodi at Wikimedia Commons