Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium (Greek: Παναθηναϊκό Στάδιο, romanized: Panathinaïkó Stádio, [panaθinaiˈko sˈtaðio])[lower-alpha 1] or Kallimarmaro (Καλλιμάρμαρο, [kaliˈmarmaro], lit. "beautiful marble")[3][4] is a multi-purpose stadium in Athens, Greece. One of the main historic attractions of Athens,[5] it is the only stadium in the world built entirely of marble.[4]

Kallimarmaro | |

| |

.jpg.webp) Panathenaic Stadium in 2014 | |

| Location | Pangrati, Athens, Greece |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°58′6″N 23°44′28″E |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Hellenic Olympic Committee |

| Capacity | 144 AD: 50,000 1896: 80,000 Current: 45,000[1] |

| Record attendance | 80,000 (AEK Athens vs Slavia VŠ Praha, 1968) |

| Construction | |

| Built | 6th century BC (racecourse) c. 330 BC (in limestone by Lykourgos) c. 144 AD (in marble by Herodes Atticus) |

| Renovated | 1896 |

| Architect | Anastasios Metaxas (1896 renovation) |

A stadium was built on the site of a simple racecourse by the Athenian statesman Lykourgos (Lycurgus) c. 330 BC, primarily for the Panathenaic Games. It was rebuilt in marble by Herodes Atticus, an Athenian Roman senator, by 144 AD it had a capacity of 50,000 seats. After the rise of Christianity in the 4th century it was largely abandoned. The stadium was excavated in 1869 and hosted the Zappas Olympics in 1870 and 1875. After being refurbished, it hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the first modern Olympics in 1896 and was the venue for 4 of the 9 contested sports. It was used for various purposes in the 20th century and was once again used as an Olympic venue in 2004. It is the finishing point for the annual Athens Classic Marathon.[3] It is also the last venue in Greece from where the Olympic flame handover ceremony to the host nation takes place.[6][7]

Location

The stadium is built in what was originally a natural ravine between the two hills of Agra and Ardettos,[8] south of the Ilissos river.[9][10] It is now located in the central Athens district of Pangrati, to the east of the National Gardens and the Zappeion Exhibition Hall, to the west of the Pangrati residential district, and between the twin pine-covered hills of Ardettos and Agra. Until the 1950s, the Ilissos River (which is now covered by (and flowing underneath) Vasileos Konstantinou Avenue) ran in front of the stadium's entrance, with the spring of Kallirrhoe, the sanctuary of Pankrates (a local hero), and the Cynosarges public gymnasium nearby.

History

Originally, since the 6th century BC, a racecourse stood at the site. It hosted the Panathenaic Games (also known as the Great Panathenaea), a religious and athletic festival celebrated every four years in honour of the goddess Athena. The racecourse had no formal seating and the spectators sat on the natural slopes on the side of the ravine.[11]

Stadium of Lykourgos

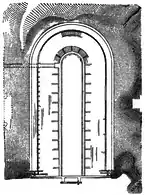

In the 4th century BC the Athenian statesman Lykourgos (Lycurgus) built an 850-foot (260 m) long stadium of poros stone.[12] Tiers of stone benches were arranged around the track. The track was 669 feet (204 m) long and 110 feet (34 m) wide.[11] In the Lives of the Ten Orators Pseudo-Plutarch writes that a certain Deinas, the owner of the property where the stadium was built was persuaded by Lykourgos to donate the land to the city and Lykourgos leveled a ravine.[13][14] IG II² 351 (dated 329 BC), records that Eudemus of Plataea gave 1000 yoke of oxen for the construction of the stadium and theater. According to Romano the "reference to the large number of oxen, indicating a vast undertaking, and the use of the word charadra have suggested the kind of building activity that would have been needed to prepare the natural valley between the two hills near the Ilissos."[14] The stadium of Lykourgos is believed to have been completed for the Panathenaic Games of 330/329 BC.[19] Donald Kyle suggests that it is possible that Lykourgos did not build but "renovated or embellished a pre-existing facility to give it monumental stature."[20] According to Richard Ernest Wycherley the stadium probably had stone seating "only for a privileged few."[15]

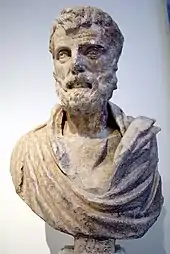

Reconstruction by Herodes Atticus

Herodes Atticus, an Athenian who rose to the highest echelons of power in Rome, was responsible for numerous structures in Greece. In Athens he is best known for the reconstruction of the Panathenaic Stadium.[21][lower-alpha 2] Tobin suggests that "Herodes built the stadium soon after [his father] Atticus's death, which occurred around A.D. 138. The first Greater Panathenaia following his father's demise was 139/40, and it is probable that at that time Herodes promised the refurbishment of the stadium. According to Philostratus, it was completed four years later, which would have been in 143/4."[21] These dates (139/140-143-144 AD) are now widely cited as construction dates of the stadium of Herodes Atticus.[23][12][17] Welch writes that the stadium was completed by 143, in time for Panathenaic festival.[10]

_-_British_Museum.jpg.webp)

The new stadium was built completely of ashlar masonry[24] in Pentelic marble,[11][12] using minimal concrete.[24] The stadium was built at a time of resurgence of Greek culture in the mid-2nd century. Although the stadium was a "quintessentially Greek architectural type",[10] it was "Roman in scale" with a massive capacity of 50,000,[15] which is roughly the same as that of the Stadium of Domitian in Rome.[24] Stadia of the Classical and Hellenistic periods were smaller.[24][8] According to Welch there is a possibility that criminals were executed in the stadium, however, no evidence exists.[25]

A marble throne from the prohedria (front row seating) of the stadium is kept in the British Museum. One side of the throne includes a relief showing an olive tree and a table on which rests set of wreaths and a Panathenaic amphora. The front leg is in the form of an owl.[26] Ten similar thrones have been found around Athens.[27]

Herodes Atticus built it as "an architectural means of self-representation, and it did something analogous. The architecture of the building makes allusions to the Classical past while remaining unmistakably modern. It is Roman in scale, but it self-consciously rejects the distinguishingly Roman features of monumental facade and extensive vaulting."[24] The seats of the cavea were decorated with owls in relief, which symbolize Athena.[24] Katherine Welch wrote in a 1998 article "Greek stadia and Roman spectacles":[28]

Though traditional in building materials and construction technique, the track included modern features that were specifically designed to accommodate Roman entertainments. [...] It may thus be argued that the Panathenaic Stadium of Herodes Atticus, who was both Athens' leading son and a Roman consul, represents a middle ground between two conflicting cultural expectations. Its architectural for was self-consciously old-fashioned, yet in scale and function the building was thoroughly modern. Herodes Atticus built a new Panathenaic Stadium whose architecture reflected the prevailing nostalgia for Classical Greece but whose functions reflected the new realities of Roman power. While the building continued to be used chiefly for athletic competitions, its running track was also a place where during the imperial cult festival wild animals were slaughtered and hardened criminals (gladiators) fought, bled, and died.

Abandonment

After Hellenistic festivals and bloody spectacles were banned by Roman Emperor Theodosius I in the late 4th century, the stadium was abandoned and fell into ruin. Gradually, its significance was forgotten and a field of wheat covered the site.[23] During the Latin rule of Athens, Crusader knights held feats of arms at the stadium. A 15th century traveler saw "not only several rows of white marble benches, but also the portico at the entrance of the Stadion, which he calls the North entrance, and the Stoa round the koilon, which he calls the South entrance."[29] The derelict stadium's marbles were incorporated into other buildings. European travelers wrote of "magical rites enacted by young Athenian maidens in the ruined vaulted passage, aimed at finding a good husband."[16]

Excavations and Zappas Olympics

Following Greece's independence, archaeological excavation as early as 1836 uncovered traces of the stadium of Herodes Atticus. Further, more thorough, excavation was conducted by the German-born architect Ernst Ziller in 1869–70.[30] Some marbles of the stadium and four Hermai were found.[31] The Zappas Olympics, an early attempt to revive the ancient Olympic Games, were held at the stadium in 1870 and 1875. They were sponsored by the Greek benefactor Evangelis Zappas.[16] The games had an audience of 30,000 people.[32]

1896 Olympics

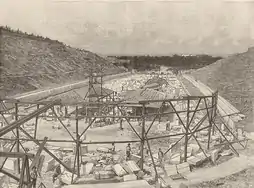

The Greek government, through crown prince Constantine, requested the Egypt-based Greek businessman George Averoff, to sponsor the second refurbishment of the stadium prior to the 1896 Olympics.[33] Based on the findings of Ziller, a reconstruction plan was prepared by the architect Anastasios Metaxas in the mid-1890s.[3] Darling writes that "He duplicated the dimensions and design of the second-century structure, arranging the tiers of seats around the U-shaped track."[4] It was rebuilt in Pentelic marble and is "distinguished by its high degree of fidelity to the ancient monument of Herodes."[16] Averoff donated 920,000 drachmas to this project.[4][33] As a tribute to his generosity, a statue of Averoff was constructed and unveiled on 5 April 1896 outside the stadium. It stands there to this day.[34]

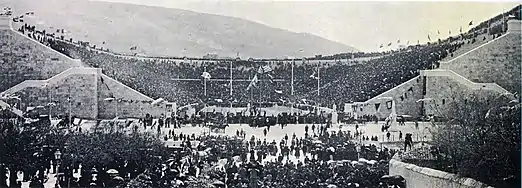

The stadium held the opening and closing ceremonies of the 1896 Olympics.[35] On 6 April (25 March according to the Julian calendar then in use in Greece), the games of the First Olympiad were officially opened; it was Easter Monday for both the Western and Eastern Christian Churches and the anniversary of Greece's independence.[36] The stadium was filled with an estimated 80,000 spectators, including King George I of Greece, his wife Olga, and their sons. Most of the competing athletes were aligned on the infield, grouped by nation. After a speech by the president of the organizing committee, Crown Prince Constantine, his father officially opened the games.[37] The stadium also served as the venue for Athletics, Gymnastics, Weightlifting and Wrestling.[38]

Reconstruction works at the stadium, 1895

Reconstruction works at the stadium, 1895 The first day of the 1896 Olympics

The first day of the 1896 Olympics Entrance of participants to the stadium. The Acropolis is seen in the background.

Entrance of participants to the stadium. The Acropolis is seen in the background. The opening ceremony

The opening ceremony

1906 Intercalated Games

The stadium hosted the 1906 Intercalated Games from 22 April to 2 May.[39]

Home of AEK Basketball Club

From the mid- to late 1960s, the stadium was used by AEK Basketball Club. On 4 April 1968, the 1967–68 FIBA European Cup Winners' Cup final was hosted in the stadium where AEK defeated Slavia VŠ Praha in front of around 80,000 seated spectators inside the arena and another 40,000 standing spectators. It is believed that since that game the Panathenaic Stadium holds the world record attendance for any basketball game as of 2021.[40]

Regime of the Colonels

During the Regime of the Colonels (1967–74), large annual events were held at the stadium, particularly the "Festival of the Military Virtues of the Greeks" (in late August-early September) and the "Revolution of 21 April 1967", the date of the coup that brought the right-wing regime to power. In these festivals, the stadium, "with its aura of antiquity stood as a monument to Greek rebirth, national pride, and international interest." The dictators exploited its setting to showcase their supposed popularity and propagate their new, "revolutionary" political culture.[41]

2004 Olympics

The stadium "needed no major refurbishing" prior to the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens.[42] During the games the stadium hosted the archery competition (15–21 August) and was the finish of the Marathon for both women (22 August) and men (29 August).[43][44]

2011 Special Olympics World Summer Games

The opening ceremony of the 2011 Special Olympics World Summer Games were held here which featured special appearances such as Stevie Wonder, Vanessa Williams and Zhang Ziyi. The games ran from 25 June to 5 July.

Concert venue

On occasion, the stadium has also been used as a venue for selected musical and dance performances.

- In April 1916 Giuseppe Verdi's Aida was staged at the stadium.[45]

- On 22 July 1982, The Talking Heads played here. Tom Tom Club was the leadup band. The crowd got out of control and tore down side barriers allowing everyone to get to the front of the stage.

- On 23–24 July 1985 the "Rock in Athens" Festival took place featuring singers and bands like Depeche Mode, The Stranglers, Culture Club, The Cure, Talk Talk, Nina Hagen, and The Clash.[45]

- On 2 October 1988 the "Live AID – Concert for AIDS" was held in the stadium including artists like Bonnie Tyler, Joan Jett, Jerry Lee Lewis, Run–D.M.C. and Black Uhuru.[46]

- On 5 October 2008, the stadium hosted the MTV Greece launch party, with guests R.E.M., Kaiser Chiefs, C:Real and Gabriella Cilmi.[47]

- On 16 July 2018, the Scorpions gave the “Once in a Lifetime” concert at the stadium.[48]

Other concerts include those of Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo (27 June 2007)[49] and a dance performance by Joaquín Cortés (14 September 2009).[45]

Other events

The stadium hosted the opening ceremony of the 1997 World Championships in Athletics on a concept by composer Vangelis and along with the performance of soprano Montserrat Caballé.[45][50]

In more recent years, the stadium has been often used to honour the homecoming of victorious Greek athletes, most notably the Greece national football team after its victory at the UEFA Euro 2004 on 5 July 2004[45] as well as Greek medalists in recent Olympic Games.

The stadium was the venue for the Dior Cruise 2022 show. The collection drew inspiration from Ancient Greek art and Greek folk culture as well as Christian Dior's Fall 1951 campaign photoshoot on the Acropolis. The show was attended by many A-listers, such as Anya Taylor-Joy, Cara Delevingne, Jisoo and many other global and Greek stars.

Architecture

Katherine Welch described the stadium as a "great marble flight of steps terraced into the contours of a U-shaped ravine — splendid in materials but ostentatiously simple in construction technique."[24]

Influence

The Panathenaic Stadium influenced the stadium architecture in the West in the 20th century. Harvard Stadium in Boston, built in 1903, was modeled after the Panathenaic Stadium.[51][52] Designated as a National Historic Landmark, it is the first collegiate athletic stadium in the United States. Deutsches Stadion in Nuremberg, designed by Albert Speer, was also modeled on the Panathenaic Stadium.[53][54] Speer was inspired by the stadium when he visited Athens in 1935.[55] The stadium was designed for some 400,000 spectators and was one of the monumental structures of the Nazi regime. Its construction began in 1937, but was never completed.

Commemorations

The Panathenaic Stadium was selected as the main motif for a high value euro collectors' coin; the €100 Greek The Panathenaic Stadium commemorative coin, minted in 2003 to commemorate the 2004 Olympics. In the obverse of the coin, the stadium is depicted. It is shown on the obverse of all Olympic medals awarded in the 2004 Olympics, and it was also used for the succeeding Summer Olympics in Beijing in 2008, in London in 2012, in Rio de Janeiro in 2016, and in Tokyo in 2021.

Gallery

Atlas von Athen, Berlin, 1878

Atlas von Athen, Berlin, 1878

View from Mt. Lycabettus at night

View from Mt. Lycabettus at night.jpg.webp) Discobolus statue outside the stadium by Konstantinos Dimitriadis

Discobolus statue outside the stadium by Konstantinos Dimitriadis

- Panorama of the Panathenaic stadium from the entrance

See also

References

- Notes

- Ancient Greek: στάδιον Παναθηναικόν, romanized: stádion Panathēnaikón, as spelled by Philostratus.[2]

- The dominant view is that Herodes Atticus built the stadium on the site of the Lykourgan stadium.[10] However, Romano suggested a long terrace at the Pnyx hill was the location of the Lykourgan stadium because when Ernst Ziller excavated the site of the Panathenaic Stadium he "found no trace of an earlier stadium."[22] Miller et al. criticize Romano's proposed location: "There is certainly no indication in Ziller's account that he was even concerned with looking for traces of anything earlier that the Stadium of Herodus Atticus."[13]

- References

- "Stadiums in Greece". worldstadiums.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-15. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

Multi-use Athens Panathenaic Stadium 45 000

- Welch 1998, p. 139.

- Kakissis, Joanna (15 October 2014). "36 Hours in Athens". The New York Times.

- Darling 2004, p. 135.

- Behan, Rosemary (22 March 2016). "Ultratravel cityguide: Ancient Athens is great value and affluent in all the right ways". The National. Abu Dhabi.

- "Greece hands over Olympic flame to Rio 2016 organisers". The Week. Kochi, India. 28 April 2016.

The flame that will burn for Rio Olympic Games was handed over to the Brazilian organisers in a spectacular ceremony held at Panathenaic Stadium in Athens.

- "Olympic flame handover from Greece to London". The Guardian. 17 May 2012.

The Olympic flame is due to be handed over from Greece to London this afternoon at the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens...

- "Panathenaic Stadium". culture.gr. Hellenic Republic Ministry of Culture and Sports. 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) () - Tobin 1993, p. 89.

- Welch 1998, p. 133.

- Darling 2004, p. 133.

- Dinsmoor, William Bell (1950). The Architecture of Ancient Greece: An Account of Its Historic Development. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 250. ISBN 9780819602831.

The Panathenaic stadium at Athens, 850 feet long, was constructed of poros stone by the legislator Lycurgus [...]; it was only long afterwards, at about A.D. 143, the stadium was reconstructed in Pentelic marble by Herodes Atticus.

- Miller, Stephen G.; Knapp, Robert C.; Chamberlain, David (2001). The Early Hellenistic Stadium. University of California Press. pp. 211. ISBN 9780520216778.

- Romano 1985, p. 444.

- Wycherley, Richard Ernest (1978). The Stones of Athens. Princeton University Press. p. 215.

- "History". panathenaicstadium.gr. Hellenic Olympic Committee. 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. (, )

- Miller, Stephen G. (2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780300115291.

- Abrahams, Harold. "Olympic Games". Encyclopædia Britannica.

The track-and-field events were held at the Panathenaic Stadium. The stadium, originally built in 330 bce, had been excavated but not rebuilt for the 1870 Greek Olympics and lay in disrepair before the 1896 Olympics, but through the direction and financial aid of Georgios Averoff, a wealthy Egyptian Greek, it was restored with white marble.

- [8][15][16][17][18]

- Kyle, Donald G. (1993). Athletics in Ancient Athens. BRILL. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9789004097599.

- Tobin 1993, p. 81.

- Romano 1985, pp. 444–445.

- Darling 2004, p. 134.

- Welch 1998, p. 135.

- Welch 1998, p. 137.

- "Roman marble throne, known as 'The Biel Throne', from the prohedria of the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens". britishmuseum.org.

- Cecconi 2020, p. 443.

- Welch 1998, pp. 137–138.

- Polites 1896, p. 48.

- Tobin 1993, p. 82.

- Hellenic Olympic Committee, "Panathenean Stadium", informative pamphlet, not dated (after 2004).

- Young 1996, Chapter 4

- Young 1996, p. 128.

- "George Averoff Dead: A Benefactor of Greece and Egypt" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 August 1899.

- Young 1996, p. 153.

- Martin, David E.; Gynn, Roger W. H. (2000). "The Olympic Marathon". Running through the Ages. Human Kinetics. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-88011-969-1. OCLC 42823784.

- Athens 1896 – Games of the I Olympiad, International Olympic Committee

- "The first Modern Olympic Games". panathenaicstadium.gr. Hellenic Olympic Committee. 2011.

- Polley, Martin (2013). The British Olympics: Britain's Olympic Heritage 1612-2012. English Heritage. pp. 101. ISBN 9781848022263.

...staged their first Intercalated Games, held once again at the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens, from April 22 to May 2, 1906.

- "Partizan sets crowd record at Belgrade Arena!". euroleague.net. Euroleague. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016.

- Van Steen, Gonda (2015). Stage of Emergency: Theater and Public Performance Under the Greek Military Dictatorship of 1967-1974. Oxford University Press. pp. 164–167. ISBN 9780198718321.

- Robbins, Liz (18 July 2004). "The Hurdles Before the Games". The New York Times.

- Official Report of the XXVIII Olympiad (PDF). Vol. 2. Athens Organising Committee for the Olympic Games. November 2005. pp. 237, 242, 244. ISBN 960-88101-8-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2008.

- "Athens 2004". panathenaicstadium.gr. Hellenic Olympic Committee. 2011.

- "Memorable moments". panathenaicstadium.gr. Hellenic Olympic Committee. 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) () - Papadimitriou, Lena (24 May 1998). "10 ροκ συναυλίες που δεν θα ξεχάσουμε [10 rock concerts that we will not forget]". To Vima (in Greek).

- "R.E.M. Help Welcome MTV Greece At Concert In Athens". www.mtv.com. 6 October 2008.

- "Athens Gets Ready to Rock With Scorpions". www.greece.greekreporter.com. 16 July 2018.

- "Placido Domingo – Γιατροί Χωρίς Σύνορα – Μια φωνή για το Νταρφούρ". www.hotstation.gr (in Greek). 6 June 2007.

- "March with Me - Vangelis with Montserrat Caballe (Live in Athens - Greece)". dailymotion.com. 12 September 2015.

- Guiliano, Jennifer (2015). Indian Spectacle: College Mascots and the Anxiety of Modern America. Rutgers University. p. 27. ISBN 9780813565569.

The first modern stadium was built in 1903 at Harvard University. Modeled on the Olympic Panathenaic stadium that debuted in Athens, Greece, in 1896...

- Williams, Jack (22 November 2014). "Harvard triumph over Yale to show heart of The Game is still beating strong". The Guardian.

...the century-old design based on the Panathenaic Stadium in Athen, which hosted the first modern Olympic Games, in 1896...

- Brockmann, Stephen (2006). Nuremberg: The Imaginary Capital. Camden House Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 9781571133458.

Speer modeled [...] the planned Deutsches Stadion (German stadium) on the Olympic stadium in ancient Athens.

- Landfester, Manfred [in German]; Cancik, Hubert [in German]; Schneider, Helmuth, eds. (2008). Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Classical tradition, Volume 3. Brill. p. 816. ISBN 9789004142237.

A 'Deutsches Stadion' was to copy the horseshoe shape of the stadium in Athens, renovated in 1896.

- Karow, Yvonne (1997). Deutsches Opfer: Kultische Selbstauslöschung auf den Reichsparteitagen der NSDAP (in German). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 38. ISBN 9783050031408.

Deutsches Stadion (Modell) der typischen Form des langgestreckten Hufeisens – Speer nennt das Athener Stadion des Herodes Atticus, das ihn bei seinem Besuch 1935 tief beeindruckte, als architektonisches Vorbild... translation: Deutsches Stadion (model) of the typical shape of the elongated horseshoe – Speer called the Athens Stadium of Herodes Atticus, the deeply impressed him during his visit in 1935 as an architectural model...

Bibliography

- Excavation reports

- Ziller, Ernst (1870). "Ausgrabung am panathenaischen Stadion". Zeitschrift für Bauwesen (in German). 20: 485–492.

- Lampros, Spyridon P. (1870). Το Παναθηναϊκόν Στάδιον και αι εν αυτώ ανασκαφαί : Εκθέσεις αναγνωσθείσαι εν τω Φιλολογικώ Συλλόγω ο Παρνασσός. Athens: Ν. Γ. Πάσσαρη.

- Ampelas, Alex (1906). Ολίγαι λέξεις περί σταδίων και δη του Παναθηναϊκού. Athens: Estia.

- Gasparri, Carlo (1975). "Lo stadio panatenaico. Documenti e testimonianze per una riconsiderazione dell'edificio di Erode Attico". ASAtene (in Italian). 36–37: 313–392.

- Discussions

- Cecconi, Niccolò (2020). "Lo Stadio Panatenaico". Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente. 98: 417–455.

- Darling, Janina K. (2004). "Panathenaic Stadium, Athens". Architecture of Greece. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 133–135. ISBN 9780313321528.

- Kalligas, P. G. (2009). "Το Παναθηναϊκό Στάδιο: Μία Νέα Ερμηνεία". Αρχαιολογία Και Τέχνες. 113: 86–94.

- Mylonas, P. M. (1997). "Στοιχεία από την παλαιότερη και την πρόσφατη ιστορία του Παναθηναϊκού Σταδίου". PAA: 452–496.

- Papanicolaou-Christensen, Aristea (2003). The Panathenaic Stadium: Its history over the centuries. Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece. ISBN 9789608557376.

- Polites, N. G. (1896). "The Panathenaic Stadion". In Lambros, S. P.; Polites, N. G. (eds.). The Olympic Games: B.C. 776 – A.D. 1896 (PDF). London: H. Grevel and Co. pp. 31–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- Rife, Joseph L. (2008). "The Burial of Herodes Atticus: Élite Identity, Urban Society, and Public Memory in Roman Greece". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 128: 92–127. ISSN 0075-4269.

- Romano, David Gilman (1985). "The Panathenaic Stadium and Theater of Lykourgos: A Re-Examination of the Facilities on the Pnyx Hill". American Journal of Archaeology. 89 (3): 441–454. doi:10.2307/504359. JSTOR 504359. S2CID 191403660.

- Tobin, Jennifer (1993). "Some New Thoughts on Herodes Atticus's Tomb, His Stadium of 143/4, and Philostratus VS 2.550". American Journal of Archaeology. 97 (1): 81–89. doi:10.2307/505840. hdl:11693/48694. JSTOR 505840. S2CID 191509757.

- Welch, Katherine (1998). "Greek stadia and Roman spectacles: Asia, Athens, and the tomb of Herodes Atticus". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 11: 117–145. doi:10.1017/S1047759400017220. S2CID 160360888.

- Williams, Dyfri (2015). "The Panathenaic Stadium from the Hellenistic to the Roman Period: Panathenaic Prize-Amphorae and the Biel Throne". In Palagia, Olga; Spetsieri-Choremi, Alkestis (eds.). The Panathenaic Games: Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Athens, May 11-12, 2004. Oxbow Books. pp. 147–158. ISBN 978-1-78297-982-1.

- Young, David C. (1996). The Modern Olympics: A Struggle for Revival. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7207-3.

_pictogram.svg.png.webp)