Kamadhenu

Kamadhenu (Sanskrit: कामधेनु, [kaːmɐˈdʱeːnʊ], Kāmadhenu), also known as Surabhi (सुरभि, Surabhi or सुरभी, Surabhī[1]), is a divine bovine-goddess described in Hinduism as the mother of all cows. She is a miraculous cow of plenty who provides her owner whatever they desire and is often portrayed as the mother of other cattle. In iconography, she is generally depicted as a white cow with a female head and breasts, the wings of a bird, and the tail of a peafowl or as a white cow containing various deities within her body. Kamadhenu is not worshipped independently as a goddess. Rather, she is honored by the Hindu veneration of cows, who are regarded as her earthly embodiments.

| Kamadhenu | |

|---|---|

The Cow Mother Goddess of Cows | |

Sculpture of Kamadhenu at the Batu Caves, Malaysia | |

| Other names | Surabhi |

| Devanagari | कामधेनु |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Kāmadhenu |

| Affiliation | Devi |

| Abode | Goloka, Patala or the hermitages of sages, Jamadagni and Vashista |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Kashyapa |

| Children | Nandini, Dhenu, Harschika and Subhadra |

Hindu scriptures provide diverse accounts of the birth of Kamadhenu. While some narrate that she emerged from the churning of the cosmic ocean, others describe her as the daughter of the creator god Daksha, and as the wife of the sage Kashyapa. Still other scriptures narrate that Kamadhenu was in the possession of either Jamadagni or Vashista (both ancient sages), and that kings who tried to steal her from the sage ultimately faced dire consequences for their actions. Kamadhenu plays the important role of providing milk and milk products to be used in her sage-master's oblations; she is also capable of producing fierce warriors to protect him. In addition to dwelling in the sage's hermitage, she is also described as dwelling in Goloka—the realm of the cows—and Patala, the netherworld.

Etymology

Kamadhenu is often addressed by the proper name Surabhi or Shurbhi, which is also used as a synonym for an ordinary cow.[2] Professor Jacobi considers the name Surabhi—"the fragrant one"—to have originated from the peculiar smell of cows.[3] According to the Monier Williams Sanskrit–English Dictionary (1899), Surabhi means fragrant, charming, pleasing, as well as cow and earth. It can specifically refer to the divine cow Kamadhenu, the mother of cattle who is also sometimes described as a Matrika ("mother") goddess.[4] Other proper names attributed to Kamadhenu are Sabala ("the spotted one") and Kapila ("the red one").[5]

The epithets "Kamadhenu" (कामधेनु), "Kamaduh" (कामदुह्) and "Kamaduha" (कामदुहा) literally mean the cow "from whom all that is desired is drawn"—"the cow of plenty".[5][6] In the Mahabharata and Devi Bhagavata Purana, in the context of the birth of Bhishma, the cow Nandini is given the epithet Kamadhenu.[7] In other instances, Nandini is described as the cow-daughter of Surabhi-Kamadhenu. The scholar Vettam Mani considers Nandini and Surabhi to be synonyms of Kamadhenu.[2]

Iconography and symbolism

According to Indologist Madeleine Biardeau, Kamadhenu or Kamaduh is the generic name of the sacred cow, who is regarded as the source of all prosperity in Hinduism.[5] Kamadhenu is regarded as a form of Devi (the Hindu Divine Mother)[8] and is closely related to the fertile Mother Earth (Prithvi), who is often described as a cow in Sanskrit.[5][8] The sacred cow denotes "purity and non-erotic fertility, ... sacrificing and motherly nature, [and] sustenance of human life".[8]

Frederick M. Smith describes Kamadhenu as a "popular and enduring image in Indian art".[9] All the gods are believed to reside in the body of Kamadhenu—the generic cow. Her four legs are the scriptural Vedas; her horns are the triune gods Brahma (tip), Vishnu (middle) and Shiva (base); her eyes are the sun and moon gods, her shoulders the fire-god Agni and the wind-god Vayu and her legs the Himalayas. Kamadhenu is often depicted in this form in poster art.[9][10]

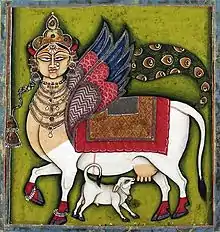

Another representation of Kamadhenu shows her with the body of a white Zebu cow, crowned woman's head, colourful eagle wings and a peacock's tail. According to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, this form is influenced by the iconography of the Islamic Buraq, who is portrayed with a horse's body, wings, and a woman's face. Contemporary poster art also portrays Kamadhenu in this form.[9][11]

A cow, identified with Kamadhenu, is often depicted accompanying the god Dattatreya. In relation to the deity's iconography, she denotes the Brahminical aspect and Vaishnava connection of the deity contrasting with the accompanying dogs—symbolizing a non-Brahminical aspect. She also symbolizes the Panch Bhuta (the five classical elements) in the icon. Dattatreya is sometimes depicted holding the divine cow in one of his hands.[8]

Birth and children

The Mahabharata (Adi Parva book) records that Kamadhenu-Surabhi rose from the churning of the cosmic ocean (Samudra Manthana) by the gods and demons to acquire Amrita (ambrosia, elixir of life).[2] As such, she is regarded the offspring of the gods and demons, created when they churned the cosmic milk ocean and then given to the Saptarishi, the seven great seers.[9] She was ordered by the creator-god Brahma to give milk, and supply it and ghee ("clarified butter") for ritual fire-sacrifices.[10]

The Anushasana Parva book of the epic narrates that Surabhi was born from the belch of "the creator" (Prajapati) Daksha after he drank the Amrita that rose from the Samudra Manthana. Further, Surabhi gave birth to many golden cows called Kapila cows, who were called the mothers of the world.[3][12] The Satapatha Brahmana also tells a similar tale: Prajapati created Surabhi from his breath.[3] The Udyoga Parva Book of the Mahabharata narrates that the creator-god Brahma drank so much Amrita that he vomited some of it, from which emerged Surabhi.[2][13]

According to the Ramayana, Surabhi is the daughter of sage Kashyapa and his wife Krodhavasha, the daughter of Daksha. Her daughters Rohini and Gandharvi are the mothers of cattle and horses respectively. Still, it is Surabhi who is described as the mother of all cows in the text.[14] However, in the Puranas, such as Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana, Surabhi is described as the daughter of Daksha and the wife of Kashyapa, as well as the mother of cows and buffaloes.[2][15]

The Matsya Purana notes two conflicting descriptions of Surabhi. In one chapter, it describes Surabhi as the consort of Brahma and their union produced the cow Yogishvari, She is then described as the mother of cows and quadrupeds. In another instance, she is described as a daughter of Daksha, wife of Kashyapa and the mother of cows.[16] The Harivamsa, an appendix of the Mahabharata, calls Surabhi the mother of Amrita (ambrosia), Brahmins, cows and Rudras.[17]

The Devi Bhagavata Purana narrates that Krishna and his lover Radha were enjoying dalliance, when they thirsted for milk. So, Krishna created a cow called Surabhi and a calf called Manoratha from the left side of his body, and milked the cow. When drinking the milk, the milk pot fell on the ground and broke, spilling the milk, which became the Kshirasagara, the cosmic milk ocean. Numerous cows then emerged from the pores of Surabhi's skin and were presented to the cowherd-companions (Gopas) of Krishna by him. Then Krishna worshipped Surabhi and decreed that she—a cow, the giver of milk and prosperity—be worshipped at Diwali on Bali Pratipada day.[2][18]

Various other scriptural references describe Surabhi as the mother of the Rudras including Nirrti (Kashyapa being the father), the cow Nandini and even the serpent-people nāgas.[19] The Mahabharata also makes a passing reference to Surabhi as the mother of Nandini (literally "daughter") in the context of the birth of Bhishma, an incarnation of a Vasu deity. Nandini, like her mother, is a "cow of plenty" or Kamadhenu, and resides with sage Vashista. Nandini is stolen by the divine Vasus and thus cursed by the sage to be born on the earth.[20] The Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa mentions that king Dilipa—an ancestor of god Rama—once passed by Kamadhenu-Surabhi, but failed to pay respects to her, thus incurring the wrath of the divine cow, who cursed the king to go childless. So, since Kamadhenu had gone to Patala, the guru of Dilipa, Vasistha advised the king to serve Nandini, Kamadhenu's daughter who was in the hermitage. The king and his wife propitiated Nandini, who neutralized her mother's curse and blessed the king to have a son, who was named Raghu.[21]

In the Ramayana, Surabhi is described to be distressed by the treatment of her sons—the oxen—in fields. Her tears are considered a bad omen for the gods by Indra, the god-king of heaven.[14] The Vana Parva book of the Mahbharata also narrates a similar instance: Surabhi cries about the plight of her son—a bullock, who is overworked and beaten by his peasant-master. Indra, moved by Surabhi's tears, rains to stop the ploughing of the tormented bullock.[22]

Wealth and protector of the Brahmin

In Hindu Religion, Kamadhenu is often associated with the Brahmin ("priest class" including sages), whose wealth she symbolizes. Cow's milk and its derivatives such as ghee (clarified butter) are integral parts of Vedic fire sacrifices, which are conducted by Brahmin priests; thus the ancient Kamadhenu is sometimes also referred to the Homadhenu—the cow from whom oblations are drawn. Moreover, the cow also offers the Brahmin—who is prohibited to fight—protection against abusive kings who try to harm them. As a goddess, she becomes a warrior, creating armies to protect her master and herself.[5]

Jamadagni's cow

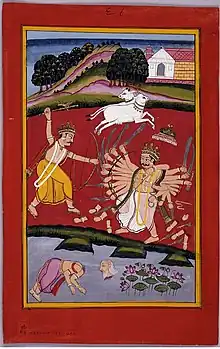

A legend narrates that the sacred cow Kamadhenu resided with sage Jamadagni. The earliest version of the legend, which appears in the epic Mahabharata, narrates that the thousand-armed Haihaya king, Kartavirya Arjuna, destroyed Jamadagni's hermitage and captured the calf of Kamadhenu. To retrieve the calf, Jamadagni's son Parashurama slew the king, whose sons in turn killed Jamadagni. Parashurama then destroyed the kshatriya ("warrior") race 21 times and his father is resurrected by divine grace.[23] Similar accounts of the abduction of the celestial cow or her calf, the killing of Jamadagni by Kartavirya Arjuna, and the revenge of Parashurama resulting in the death of Kartavirya Arjuna, exist in other texts. The Bhagavata Purana mentions that the king abducted Kamadhenu as well as her calf and Parashurama defeated the king and returned the kine to his father.[23] The Padma Purana mentions that when Kartavirya Arjuna tried to capture her, Kamadhenu, by her own power, defeated him and his army and flew off to heaven; the enraged king then killed Jamadagni.[23]

In the Brahmanda Purana, Kamadhenu creates a great city by her power to accommodate Kartavirya Arjuna's army, when they visit Jamadagni's hermitage. On returning to his kingdom, Kartavirya Arjuna's minister, Chandragupta, persuades him to capture the divine cow. The minister returns to the hermitage and tries to convince the sage to give away the cow, but to no avail, so he tries to snatch Kamadhenu with force. In the ensuing fight, the sage is killed, but Kamadhenu escapes to the sky and Chandragupta takes her calf with him instead.[23] The Brahmanda Purana narrates this Kamadhenu Sushila was given to Jamadagni by the Kamadhenu-Surabhi, who governs in Goloka.[2]

The Brahma Vaivarta Purana narrates that the celestial cow – called Kapila here – produces various weapons and an army to aid Jamadagni defeat the king's army, who had come to seize her. When the king himself challenged Jamadagni for battle, Kapila instructed her master in martial arts. Jamadagni led the army created by Kapila and defeated the king and his army several times; each time sparing the life of the king. Finally, with the aid of a divine spear granted to him by the god Dattatreya, the king killed Jamadagni.[23]

Vashista's cow

The Ramayana presents a similar account about Kamadhenu, however, here the sage is Vashista and the king is Vishvamitra. Once, king Vishwamitra with his army arrived at the hermitage of sage Vashista. The sage welcomed him and offered a huge banquet – to the army – that was produced by Sabala – as Kamadhenu is called in the text. The astonished king asked the sage to part with Sabala and instead offered thousand of ordinary cows, elephants, horses and jewels in return. However, the sage refused to part with Sabala, who was necessary for the performance of the sacred rituals and charity by the sage. Agitated, Vishwamitra seized Sabala by force, but she returned to her master, fighting the king's men. She hinted Vashista to order her to destroy the king's army and the sage followed her wish. Intensely, she produced Pahlava warriors, who were slain by Vishwamitra's army. So she produced warriors of Shaka-Yavana lineage. From her mouth emerged the Kambhojas, from her udder Barvaras, from her hind Yavanas and Shakas, and from pores on her skin, Haritas, Kiratas and other foreign warriors. Together, the army of Sabala killed Vishwamitra's army and all his sons. This event led to a great rivalry between Vashista and Vishwamitra, who renounced his kingdom and became a great sage to defeat Vashista.[24]

Abodes

Kamadhenu-Surabhi's residence varies depending on different scriptures. The Anushasana Parva of the Mahabharata tells how she was given the ownership of Goloka, the cow-heaven located above the three worlds (heaven, earth and netherworld): the daughter of Daksha, Surabhi went to Mount Kailash and worshipped Brahma for 10,000 years. The pleased god conferred goddess-hood on the cow and decreed that all people would worship her and her children – cows. He also gave her a world called Goloka, while her daughters would reside on earth among humans.[2][3][25]

In one instance in the Ramayana, Surabhi is described to live in the city of Varuna – the Lord of oceans – which is situated below the earth in Patala (the netherworld). Her flowing sweet milk is said to form Kshiroda or the Kshirasagara, the cosmic milk ocean.[14] In the Udyoga Parva book of the Mahabharata, this milk is said to be of six flavours and has the essence of all the best things of the earth.[13][26] The Udyoga Parva specifies that Surabhi inhabits the lowest realm of Patala, known as Rasatala, and has four daughters – the Dikpalis – the guardian cow goddesses of the heavenly quarters: Saurabhi in the east, Harhsika in the south, Subhadra in the west and Dhenu in the north.[3][13]

Apart from Goloka and Patala, Kamadhenu is also described as residing in the hermitages of the sages Jamadagni and Vashista. Scholar Mani explains the contradicting stories of Kamadhenu's birth and presence in the processions of many gods and sages by stating that while there could be more than one Kamadhenu, all of them are incarnations of the original Kamadhenu, the mother of cows.[2]

The Bhagavad Gita, a discourse by the god Krishna in the Mahabharata, twice refers to Kamadhenu as Kamadhuk. In verse 3.10, Krishna makes a reference to Kamadhuk while conveying that for doing one's duty, one would get the milk of one's desires. In verse 10.28, when Krishna declares to the source of the universe, he proclaims that among cows, he is Kamadhuk.[27]

In the Anushasana Parva of the Mahabharata, the god Shiva is described as having cast a curse on Surabhi. This curse is interpreted as a reference to the following legend:[28] Once, when the gods Brahma and Vishnu were fighting over who was superior, a fiery pillar—linga (symbol of Shiva)—emerged before them. It was that decided whoever found the end of this pillar was superior. Brahma flew to the skies to try to find the top of the pillar, but failed. So Brahma forced Surabhi (in some versions, Surabhi instead suggested that Brahma should lie) to falsely testify to Vishnu that Brahma had seen the top of the linga; Shiva punished Surabhi by putting a curse on her so that her bovine offspring would have to eat unholy substances. This tale appears in the Skanda Purana.[29]

Worship

Some temples and houses have images of Kamadhenu, which are worshipped.[30] However, she has never had a worship cult dedicated to her and does not have any temples where she is worshipped as the chief deity.[30][31] In Monier-Williams's words: "It is rather the living animal [the cow] which is the perpetual object of adoration".[30] Cows are often fed outside temples and worshipped regularly on all Fridays and on special occasions. Every cow to "a pious Hindu" is regarded as an avatar (earthly embodiment) of the divine Kamadhenu.[32]

See also

Notes

- Sanskrit Heritage Dictionary - सुरभि surabhi (in French)

- Mani pp. 379–81

- Jacobi, H. (1908–1927). "Cow (Hindu)". In James Hastings (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 4. pp. 225–6.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (2008) [1899]. "Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary". Universität zu Köln. p. 1232.

- Biardeau, Madeleine (1993). "Kamadhenu: The Religious Cow, Symbol of Prosperity". In Yves Bonnefoy (ed.). Asian mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (2008) [1899]. "Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary". Universität zu Köln. p. 272.

- Vijñanananda, Swami (1921–1922). "The S'rîmad Devî Bhâgawatam: Book 2: Chapter 3". Sacred texts archive. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- Rigopoulos, Antonio (1998). Dattātreya: the immortal guru, yogin, and avatāra. SUNY Press. pp. 231, 233, 243. ISBN 978-0-7914-3695-0.

- Smith, Frederick M. (2006). The self possessed: Deity and spirit possession in South Asian literature and civilization. Columbia University Press. pp. 404, pp. 402–3 (Plates 5 and 6 for the two representations of Kamadhenu). ISBN 978-0-231-13748-5.

- Venugopalam, R. (2003). "Animal Deities". Rituals and Culture of India. B. Jain Publishers. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-81-8056-373-7.

- "Kamadhenu, The Wish-Granting Cow". Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Ganguli, Kisari Mohan (1883–1896). "SECTION LXXVII". The Mahabharata: Book 13: Anusasana Parva. Sacred texts archive.

- Ganguli, Kisari Mohan (1883–1896). "SECTION CII". The Mahabharata: Book 5: Udyoga Parva. Sacred texts archive.

- Sharma, Ramashraya (1971). Socio-Political Study of the Valmiki Ramayana. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 220. ISBN 978-81-208-0078-6.

- Aadhar, Anand. "Bhagavata Purana: Canto 6: Chapter 6: The Progeny of the Daughters of Daksha". Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- A Taluqdar of Oudh (2008). The Matsya Puranam. The Sacred books of the Hindus. Vol. 2. Cosmo Publications for Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. pp. 52, 137. ISBN 978-81-307-0533-0.

- Hopkins p. 173

- Vijñanananda, Swami (1921–1922). "The S'rîmad Devî Bhâgawatam: On the anecdote of Surabhi". Sacred texts archive. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- Daniélou, Alain (1991). The histories of gods India. Inner Traditions International. pp. 102, 127, 308, 320. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- Van Buitenen, J. A. (1975). The Mahabharata: The book of the beginning. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. pp. 220–1. ISBN 978-0-226-84663-7.

- Kale, M. R. (1991). "Cantos I and II". The Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa: Cantos I – V. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. xv, xvi, 1–27. ISBN 978-81-208-0861-4.

- Van Buitenen, J. A. (1975). The Mahabharata: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. Vol. 2. University of Chicago Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- Donaldson, Thomas Eugene (1995). "The Cult of Parasurama and its Popularity in Orrisa". In Vyas, R. T. (ed.). Studies in Jaina art and iconography and allied subjects. The Director, Oriental Institute on behalf of Registar, MS, University of Baroda. pp. 163–7. ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8.

- Venkatesananda, Swami (1988). The concise Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki. SUNY Press. pp. 31–2. ISBN 978-0-88706-862-1.

- Ganguli, Kisari Mohan (1883–1896). "SECTION LXXXIII". The Mahabharata: Book 13: Anusasana Parva. Sacred texts archive.

- Hopkins pp. 16, 119

- Radhakrishan, S. (1977). "Verses 3.10, 10.28". The Bhagavadgita. Blackie & Son (India) Ltd. pp. 135, 264.

- Ganguli, Kisari Mohan. "SECTION XVII". The Mahabharata: Book 13: Anusasana Parva archive.

- Jha, D. N. (2004). The Myth of the Holy Cow. Verso Books. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-85984-424-3.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1887). Brahmanism and Hinduism:Religious Thought and Life in India. London Murray.

- White, David Gordon (2003). "Surabhi, The Mother of Cows". Kiss of the yoginī: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian contexts. University of Chicago Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-226-89483-6.

- Rao, T.A. Gopinatha (1916). Elements of Hindu iconography. Vol. 1: Part I. Madras: Law Printing House. p. 13.

References

- Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

- Hopkins, Edward Washburn (1915). Epic mythology. Strassburg K.J. Trübner. ISBN 978-0-8426-0560-1.