Sperm competition

Sperm competition is the competitive process between spermatozoa of two or more different males to fertilize the same egg[1] during sexual reproduction. Competition can occur when females have multiple potential mating partners. Greater choice and variety of mates increases a female's chance to produce more viable offspring.[2] However, multiple mates for a female means each individual male has decreased chances of producing offspring. Sperm competition is an evolutionary pressure on males, and has led to the development of adaptations to increase male's chance of reproductive success.[3] Sperm competition results in a sexual conflict between males and females.[2] Males have evolved several defensive tactics including: mate-guarding, mating plugs, and releasing toxic seminal substances to reduce female re-mating tendencies to cope with sperm competition.[4] Offensive tactics of sperm competition involve direct interference by one male on the reproductive success of another male, for instance by physically removing another male's sperm prior to mating with a female.[5][6] For an example, see Gryllus bimaculatus.

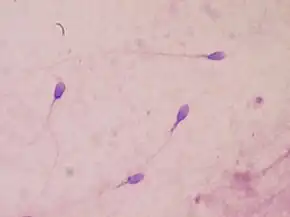

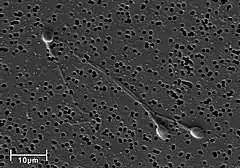

Sperm competition is often compared to having tickets in a raffle; a male has a better chance of winning (i.e. fathering offspring) the more tickets he has (i.e. the more sperm he inseminates a female with). However, sperm are not free to produce,[7] and as such males are predicted to produce sperm of a size and number that will maximize their success in sperm competition. By making many spermatozoa, males can buy more "raffle tickets", and it is thought that selection for numerous sperm has contributed to the evolution of anisogamy with very small sperm (because of the energy trade-off between sperm size and number).[8] Alternatively, a male may evolve faster sperm to enable his sperm to reach and fertilize the female's ovum first. Dozens of adaptations have been documented in males that help them succeed in sperm competition.

Defensive adaptations

.JPG.webp)

Mate-guarding is a defensive behavioral trait that occurs in response to sperm competition; males try to prevent other males from approaching the female (and/or vice versa) thus preventing their mate from engaging in further copulations.[2] Precopulatory and postcopulatory mate-guarding occurs in insects, lizards, birds and primates. Mate-guarding also exists in the fish species Neolamprologus pulcher, as some males try to "sneak" matings with females in the territory of other males. In these instances, the males guard their female by keeping her in close enough proximity so that if an opponent male shows up in his territory he will be able to fight off the rival male which will prevent the female from engaging in extra-pair copulation with the rival male.[9]

Organisms with polygynous mating systems are controlled by one dominant male. In this type of mating system, the male is able to mate with more than one female in a community.[10] The dominant males will reign over the community until another suitor steps up and overthrows him.[10] The current dominant male will defend his title as the dominant male and he will also be defending the females he mates with and the offspring he sires. The elephant seal falls into this category since he can participate in bloody violent matches in order to protect his community and defend his title as the alpha male.[11] If the alpha male is somehow overthrown by the newcomer, his children will most likely be killed and the new alpha male will start over with the females in the group so that his lineage can be passed on.[12]

Strategic mate-guarding occurs when the male only guards the female during her fertile periods. This strategy can be more effective because it may allow the male to engage in both extra-pair paternity and within-pair paternity.[13] This is also because it is energetically efficient for the male to guard his mate at this time. There is a lot of energy that is expended when a male is guarding his mate. For instance, in polygynous mate-guarding systems, the energetic costs of males is defending their title as alpha male of their community.[11] Fighting is very costly in regards to the amount of energy used to guard their mate. These bouts can happen more than once which takes a toll on the physical well-being of the male. Another cost of mate-guarding in this type of mating system is the potential increase of the spread of disease.[14] If one male has an STD, he can pass that on to the females that he's copulating with, potentially resulting in a depletion of the harem. This would be an energetic cost towards both sexes for the reason that instead of using the energy for reproduction, they are redirecting it towards ridding themselves of this illness. Some females also benefit from polygyny because extra pair copulations in females increase the genetic diversity with the community of that species.[15] This occurs because the male is not able to watch over all of the females and some will become promiscuous. Eventually, the male will not have proper nutrition, which makes the male unable to produce sperm.[16] For instance, male amphipods will deplete their reserves of glycogen and triglycerides only to have it replenished after the male is done guarding that mate.[17] Also, if the amount of energy intake does not equal the energy expended, then this could be potentially fatal to the male. Males may even have to travel long distances during the breeding season in order to find a female which absolutely drain their energy supply. Studies were conducted to compare the cost of foraging of fish that migrate and animals that are residential. The studies concluded that fish that were residential had fuller stomachs containing higher quality of prey compared to their migrant counterparts.[18] With all of these energy costs that go along with guarding a mate, timing is crucial so that the male can use the minimal amount of energy. This is why it is more efficient for males to choose a mate during their fertile periods.[13] Also, males will be more likely to guard their mate when there is a high density of males in the proximity.[2] Sometimes, organisms put in all this time and planning into courting a mate in order to copulate and she may not even be interested. There is a risk of cuckoldry of some sort, since a rival male can successfully court the female that the male originally courting her could not do.[19]

However, there are benefits that are associated with mate-guarding. In a mating- guarding system, both parties, male and female, are able to directly and indirectly benefit from this. For instance, females can indirectly benefit from being protected by a mate.[20] The females can appreciate a decrease in predation and harassment from other males while being able to observe her male counterpart.[20] This will allow her to recognize particular traits that she finds ideal so that she'll be able to find another male that emulates those qualities. In polygynous relationships, the dominant male of the community benefits because he has the best fertilization success.[12] Communities can include 30 up to 100 females and, compared to the other males, will greatly increase his chances of mating success.[11]

Males who have successfully courted a potential mate will attempt to keep them out of sight of other males before copulation. One way organisms accomplish this is to move the female to a new location. Certain butterflies, after enticing the female, will pick her up and fly her away from the vicinity of potential males.[21] In other insects, the males will release a pheromone in order to make their mate unattractive to other males or the pheromone masks her scent completely.[21] Certain crickets will participate in a loud courtship until the female accepts his gesture and then it suddenly becomes silent.[22] Some insects, prior to mating, will assume tandem positions to their mate or position themselves in a way to prevent other males from attempting to mate with that female.[21] The male checkerspot butterfly has developed a clever method in order to attract and guard a mate. He will situate himself near an area that possesses valuable resources that the female needs. He will then drive away any males that come near and this will greatly increase his chances of copulation with any female that comes to that area.[23]

In post-copulatory mate-guarding males are trying to prevent other males from mating with the female that they have mated with already. For example, male millipedes in Costa Rica will ride on the back of their mate letting the other males know that she's taken.[24] Japanese beetles will assume a tandem position to the female after copulation.[25] This can last up to several hours allowing him to ward off any rival males giving his sperm a high chance to fertilize that female's egg. These, and other, types of methods have the male playing defense by protecting his mate. Elephant seals are known to engage in bloody battles in order to retain their title as dominant male so that they are able to mate with all the females in their community.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Copulatory plugs are frequently observed in insects, reptiles, some mammals, and spiders.[2] Copulatory plugs are inserted immediately after a male copulates with a female, which reduce the possibility of fertilization by subsequent copulations from another male, by physically blocking the transfer of sperm.[2] Bumblebee mating plugs, in addition to providing a physical barrier to further copulations, contain linoleic acid, which reduces re-mating tendencies of females.[26] A species of Sonoran desert Drosophila, Drosophila mettleri, uses copulatory plugs to enable males to control the sperm reserve space females have available. This behavior ensures males with higher mating success at the expense of female control of sperm (sperm selection).

Similarly, Drosophila melanogaster males release toxic seminal fluids, known as ACPs (accessory gland proteins), from their accessory glands to impede the female from participating in future copulations.[27] These substances act as an anti-aphrodisiac causing a dejection of subsequent copulations, and also stimulate ovulation and oogenesis.[5] Seminal proteins can have a strong influence on reproduction, sufficient to manipulate female behavior and physiology.[28]

Another strategy, known as sperm partitioning, occurs when males conserve their limited supply of sperm by reducing the quantity of sperm ejected.[2] In Drosophila, ejaculation amount during sequential copulations is reduced; this results in half filled female sperm reserves following a single copulatory event, but allows the male to mate with a larger number of females without exhausting his supply of sperm.[2] To facilitate sperm partitioning, some males have developed complex ways to store and deliver their sperm.[29] In the blue headed wrasse, Thalassoma bifasciatum, the sperm duct is sectioned into several small chambers that are surrounded by a muscle that allows the male to regulate how much sperm is released in one copulatory event.[30]

A strategy common among insects is for males to participate in prolonged copulations. By engaging in prolonged copulations, a male has an increased opportunity to place more sperm within the female's reproductive tract and prevent the female from copulating with other males.[31]

It has been found that some male mollies (Poecilia) have developed deceptive social cues to combat sperm competition. Focal males will direct sexual attention toward typically non-preferred females when an audience of other males is present. This encourages the males that are watching to attempt to mate with the non-preferred female. This is done in an attempt to decrease mating attempts with the female that the focal male prefers, hence decreasing sperm competition.[32]

Offensive adaptations

Offensive adaptation behavior differs from defensive behavior because it involves an attempt to ruin the chances of another male's opportunity in succeeding in copulation by engaging in an act that tries to terminate the fertilization success of the previous male.[5] This offensive behavior is facilitated by the presence of certain traits, which are called armaments.[33] An example of an armament are antlers. Further, the presence of an offensive trait sometimes serves as a status signal. The mere display of an armament can suffice to drive away the competition without engaging in a fight, hence saving energy.[33] A male on the offensive side of mate-guarding may terminate the guarding male's chances at a successful insemination by brawling with the guarding male to gain access to the female.[2] In Drosophila, males release seminal fluids that contain additional toxins like pheromones and modified enzymes that are secreted by their accessory glands intended to destroy the sperm that have already made their way into the female's reproductive tract from a recent copulation.[5] However, this proved to be wrong because Drosophila melanogaster seminal fluid can actually protect the sperm of other males. Based on the "last male precedence" idea, some males can remove sperm from previous males by ejaculating new sperm into the female; hindering successful insemination opportunities of the previous male.[34]

Mate choice

The "good sperm hypothesis" is very common in polyandrous mating systems.[35] The "good sperm hypothesis" suggests that a male's genetic makeup will determine the level of his competitiveness in sperm competition.[35] When a male has "good sperm" he is able to father more viable offspring than males that do not have the "good sperm" genes.[35] Females may select males that have these superior "good sperm" genes because it means that their offspring will be more viable and will inherit the "good sperm" genes which will increase their fitness levels when their sperm competes.[36]

Studies show that there is more to determining the competitiveness of the sperm in sperm competition in addition to a male's genetic makeup. A male's dietary intake will also affect sperm competition. An adequate diet consisting of increased amounts of diet and sometimes more specific ratio in certain species will optimize sperm number and fertility. Amounts of protein and carbohydrate intake were tested for its effects on sperm production and quality in adult fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Studies showed these flies need to constantly ingest carbohydrates and water to survive, but protein is also required to attain sexual maturity.[37] In addition, The Mediterranean fruit fly, male diet has been shown to affect male mating success, copula duration, sperm transfer, and male participation in leks.[38] These all require a good diet with nutrients for proper gamete production as well as energy for activities, which includes participation in leks.

In addition, protein and carbohydrate amounts were shown to have an effect on sperm production and fertility in the speckled cockroach. Holidic diets were used which allowed for specific protein and carbohydrate measurements to be taken, giving it credibility. A direct correlation was seen in sperm number and overall of food intake. More specifically, optimal sperm production was measured at a 1:2 protein to carbohydrate ratio. Sperm fertility was best at a similar protein to carbohydrate ratio of 1:2. This close alignment largely factors in determining male fertility in Nauphoeta cinerea.[39] Surprisingly, sperm viability was not affected by any change in diet or diet ratios. It's hypothesized that sperm viability is more affected by the genetic makeup, like in the "good sperm hypothesis". These ratios and results are not consistent with many other species and even conflict with some. It seems there cannot be any conclusions on what type of diet is needed to positively influence sperm competition but rather understand that different diets do play a role in determining sperm competition in mate choice.

Evolutionary consequences

One evolutionary response to sperm competition is the variety in penis morphology of many species.[40][41] For example, the shape of the human penis may have been selectively shaped by sperm competition.[42] The human penis may have been selected to displace seminal fluids implanted in the female reproductive tract by a rival male.[42] Specifically, the shape of the coronal ridge may promote displacement of seminal fluid from a previous mating[43] via thrusting action during sexual intercourse.[42] A 2003 study by Gordon G. Gallup and colleagues concluded that one evolutionary purpose of the thrusting motion characteristic of intense intercourse is for the penis to “upsuck” another man's semen before depositing its own.[44]

Evolution to increase ejaculate volume in the presence of sperm competition has a consequence on testis size. Large testes can produce more sperm required for larger ejaculates, and can be found across the animal kingdom when sperm competition occurs.[45] Males with larger testes have been documented to achieve higher reproductive success rates than males with smaller testes in male yellow pine chipmunks.[45] In chichlid fish, it has been found that increased sperm competition can lead to evolved larger sperm numbers, sperm cell sizes, and sperm swimming speeds.[46]

In some insects and spiders, for instance Nephila fenestrate, the male copulatory organ breaks off or tears off at the end of copulation and remains within the female to serve as a copulatory plug.[47] This broken genitalia is believed to be an evolutionary response to sperm competition.[47] This damage to the male genitalia means that these males can only mate once.[48]

Female choice for males with competitive sperm

Female factors can influence the result of sperm competition through a process known as "sperm choice".[49] Proteins present in the female reproductive tract or on the surface of the ovum may influence which sperm succeeds in fertilizing the egg.[49] During sperm choice, females are able to discriminate and differentially use the sperm from different males. One instance where this is known to occur is inbreeding; females will preferentially use the sperm from a more distantly related male than a close relative.[49]

Post-copulatory inbreeding avoidance

Inbreeding ordinarily has negative fitness consequences (inbreeding depression), and as a result species have evolved mechanisms to avoid inbreeding. Inbreeding depression is considered to be due largely to the expression of homozygous deleterious recessive mutations.[50] Outcrossing between unrelated individuals ordinarily leads to the masking of deleterious recessive mutations in progeny.[51]

Numerous inbreeding avoidance mechanisms operating prior to mating have been described. However, inbreeding avoidance mechanisms that operate subsequent to copulation are less well known. In guppies, a post-copulatory mechanism of inbreeding avoidance occurs based on competition between sperm of rival males for achieving fertilization.[52] In competitions between sperm from an unrelated male and from a full sibling male, a significant bias in paternity towards the unrelated male was observed.[52]

In vitro fertilization experiments in the mouse, provided evidence of sperm selection at the gametic level.[53] When sperm of sibling and non-sibling males were mixed, a fertilization bias towards the sperm of the non-sibling males was observed. The results were interpreted as egg-driven sperm selection against related sperm.

Female fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were mated with males of four different degrees of genetic relatedness in competition experiments.[54] Sperm competitive ability was negatively correlated with relatedness.

Female crickets (Teleogryllus oceanicus) appear to use post-copulatory mechanisms to avoid producing inbred offspring. When mated to both a sibling and an unrelated male, females bias paternity towards the unrelated male.[55]

Empirical support

It has been found that because of female choice (see sexual selection), morphology of sperm in many species occurs in many variations to accommodate or combat (see sexual conflict) the morphology and physiology of the female reproductive tract.[56][57][58] However, it is difficult to understand the interplay between female and male reproductive shape and structure that occurs within the female reproductive tract after mating that allows for the competition of sperm. Polyandrous females mate with many male partners.[59] Females of many species of arthropod, mollusk and other phyla have a specialized sperm-storage organ called the spermatheca in which the sperm of different males sometimes compete for increased reproductive success.[57] Species of crickets, specifically Gryllus bimaculatus, are known to exhibit polyandrous sexual selection. Males will invest more in ejaculation when competitors are in the immediate environment of the female.

Evidence exists that illustrates the ability of genetically similar spermatozoa to cooperate so as to ensure the survival of their counterparts thereby ensuring the implementation of their genotypes towards fertilization. Cooperation confers a competitive advantage by several means, some of these include incapacitation of other competing sperm and aggregation of genetically similar spermatozoa into structures that promote effective navigation of the female reproductive tract and hence improve fertilization ability. Such characteristics lead to morphological adaptations that suit the purposes of cooperative methods during competition. For example, spermatozoa possessed by the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) possess an apical hook which is used to attach to other spermatozoa to form mobile trains that enhance motility through the female reproductive tract.[60] Spermatozoa that fail to incorporate themselves into mobile trains are less likely to engage in fertilization. Other evidence suggests no link between sperm competition and sperm hook morphology.[61]

Selection to produce more sperm can also select for the evolution of larger testes. Relationships across species between the frequency of multiple mating by females and male testis size are well documented across many groups of animals. For example, among primates, female gorillas are relatively monogamous, so gorillas have smaller testes than humans, which in turn have smaller testes than the highly promiscuous bonobos.[62] Male chimpanzees that live in a structured multi-male, multi-female community, have large testicles to produce more sperm, therefore giving him better odds to fertilize the female. Whereas the community of gorillas consist of one alpha male and two or three females, when the female gorillas are ready to mate, normally only the alpha male is their partner.

Regarding sexual dimorphism among primates, humans falls into an intermediate group with moderate sex differences in body size but relatively large testes. This is a typical pattern of primates where several males and females live together in a group and the male faces an intermediate number of challenges from other males compared to exclusive polygyny and monogamy but frequent sperm competition.[63]

Other means of sperm competition could include improving the sperm itself or its packaging materials (spermatophore).[64]

The male black-winged damselfly provides a striking example of an adaptation to sperm competition. Female black-winged damselflies are known to mate with several males over the span of only a few hours and therefore possess a receptacle known as a spermatheca which stores the sperm. During the process of mating the male damselfly will pump his abdomen up and down using his specially adapted penis which acts as a scrub brush to remove the sperm of another male. This method proves quite successful and the male damselfly has been known to remove 90-100 percent of the competing sperm.[65]

A similar strategy has been observed in the dunnock, a small bird. Before mating with the polyandrous female, the male dunnock pecks at the female's cloaca in order to peck out the sperm of the previous male suitor.[66]

In the fly Dryomyza anilis, females mate with multiple males. It benefits the male to attempt to be the last one to mate with a given female.[67] This is because there seems to be a cumulative percentage increase in fertilization for the final male, such that the eggs laid in the last oviposition bout are the most successful.

A notion emerged in 1996 that in some species, including humans, a significant fraction of sperm cannot fertilize the egg; rather these sperm were theorized to stop the sperm from other males from reaching the egg, e.g. by killing them with enzymes or by blocking their access. This type of sperm specialization became known popularly as "kamikaze sperm" or "killer sperm", but most follow-up studies to this popularized notion have failed to confirm the initial papers on the matter.[68][6] While there is also currently little evidence of killer sperm in any non-human animals[69] certain snails have an infertile sperm morph ("parasperm") that contains lysozymes, leading to speculation that they might be able to degrade a rival's sperm.[70]

The parasitoid wasp Nasonia vitripennis, mated females can choose whether or not to lay a fertilized egg (which develops into a daughter) or an unfertilized egg (which develops into a son), therefore females suffer a cost from mating, as repeated matings constrain their ability to allocate sex in their offspring. The behaviour of these kamikaze-sperm is referred to in academic literature as "sperm-blocking", using basketball as a metaphor.[71]

Sperm competition has led to other adaptations such as larger ejaculates, prolonged copulation, deposition of a copulatory plug to prevent the female re-mating, or the application of pheromones that reduce the female's attractiveness. The adaptation of sperm traits, such as length, viability and velocity might be constrained by the influence of cytoplasmic DNA (e.g. mitochondrial DNA);[72] mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother only and it is thought that this could represent a constraint in the evolution of sperm.

See also

References

- Parker, Geoffrey A. (1970). "Sperm competition and its evolutionary consequences in the insects". Biological Reviews. 45 (4): 525–567. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1970.tb01176.x. S2CID 85156929.

- Stockley, P (1997). "Sexual conflict resulting from adaptations to sperm competition". Trends Ecol. Evol. 12 (4): 154–159. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01000-8. PMID 21238013.

- Wedell, Nina; Gage, Matthew J.G.; Parker, Geoffrey A. (2002). "Sperm competition, male prudence and sperm-limited females". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 17 (7): 313–320. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02533-8.

- Simmons, L.W (2001). Competition and its Evolutionary Consequences in the Insects. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691059884.

- Birkhead, T.R; Pizzari, Tommaso (2002). "Postcopulatory sexual selection" (PDF). Nat. Rev. Genet. 3 (4): 262–273. doi:10.1038/nrg774. PMID 11967551. S2CID 10841073.

- Baker, Robin (1996). Sperm Wars: The Science of Sex. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-7881-6004-4. OCLC 37369431.

- Olsson et al., 1997; Wedell et al., 2002

- Jiang-Nan Yang (2010). "Cooperation and the evolution of anisogamy". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 264 (1): 24–36. Bibcode:2010JThBi.264...24Y. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.01.019. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 20097207.

- Kokko, H; Monaghan (2001). "Predicting the direction of sexual selection". Ecology Letters. 4 (2): 159–165. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00212.x.

- Slavsgold, H (1994). "Polygyny in birds: the role of competition between females for male parental care". American Naturalist. 143: 59–94. doi:10.1086/285596. S2CID 84467229.

- Le Beouf (1972). "Sexual behavior in the Northern Elephant seal Mirounga angustirostris". Behaviour. 41 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1163/156853972x00167. PMID 5062032.

- Boyd, R; Silk, J.B. (2009). How Humans Evolved. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Hasselquist, D; Bensch, Staffan (1991). "Trade-off between mate guarding and mate attraction in the polygynous great reed warbler". Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 28 (3): 187–193. doi:10.1007/BF00172170. S2CID 25256043.

- Thrall, PH; Antonovics, J; Dobson, AP (2000). "Sexually transmitted diseases in polygynous mating systems: prevalence and impact on reproductive success". Proc Biol Sci. 267 (1452): 1555–1563. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1178. PMC 1690713. PMID 11007332.

- Davie, Nicholas B; Krebs, John R; Dobson, Stuart A (2012). An introduction to behavioural ecology. London: Wiley- Blackwell. ISBN 9781444339499.

- Miki, K (2007). "Energy metabolism and sperm function". Society of Fertility Supplement. 65: 309–325. PMID 17644971.

- Scharf, I; Peter, F; Martin, O. Y. (2013). "Reproductive Trade-Off and Direct Costs for Males in arthropods". Evolutionary Biology. 40 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1007/s11692-012-9213-4. S2CID 14120264.

- Chapman, Ben B; Eriksen, Anders; Baktoft, Henrik; Jakob, Brodersen; Nilsson, P. Anders; Hulthen, Kaj; Brönmark, Christer; Hansson, Lars- Anders; Grønkjær, Peter; Skov, Christian (2013). "A Foraging Cost of Migration for a Partially Migratory Cyprinid Fish". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e61223. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...861223C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061223. PMC 3665772. PMID 23723967.

- Buss, DM (2016). The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465093304.

- Elias, D.O.; Sivalinghem, S; Mason, A.C.; Andrade, M.C.B.; Kasumovic, M.M. (2014). "Mate-guarding courtship behaviour: Tactics in a changing world" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 97: 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.08.007. S2CID 27908768.

- Thornhill, R; Alcock, J (1983). The evolution of insect mating systems. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Alexander, RD (1962). "Evolutionary change in cricket acoustical communication" (PDF). Evolution. 16 (4): 443–467. doi:10.2307/2406178. hdl:2027.42/137461. JSTOR 2406178.

- Bennett, Victoria J; Smith, Winston P; Betts, Matthew (2011). "Evidence for Mate Guarding Behavior in the Taylor's Checkerspot Butterfly" (PDF). Journal of Insect Behavior. 25 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1007/s10905-011-9289-1. S2CID 16322822.

- Adolph, S.C.; Gerber, M.A. (1995). "Mate guarding. Mating success and body size in the tropical millipede Nyssodesimus python". Southwestern Naturalist. 40 (1): 56–61.

- Sacki, Yoriko; Kruse, Kip C; Switzer, Paul V (2005). "The social environment affects mate guarding behavior in Japanese Beetles Popillia japonica". Journal of Insect Science. 15 (8): 1–6. doi:10.1673/031.005.1801.

- Baer, B.; Morgan, E. D.; Schmid-Hempel, P. (2001). "A nonspecific fatty acid within the bumblebee mating plug prevents females from remating". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (7): 3926–3928. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.3926B. doi:10.1073/pnas.061027998. PMC 31155. PMID 11274412.

- McGraw, Lisa A.; Gibson, Greg; Clark, Andrew G.; Wolfner, Mariana F. (2004). "Genes Regulated by Mating, Sperm, or Seminal Proteins in Mated Female Drosophila melanogaster". Current Biology. 14 (16): 1509–1514. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.028. PMID 15324670. S2CID 17056259.

- Clark, Nathaniel L.; Swanson, Willie J. (2005). "Pervasive Adaptive Evolution in Primate Seminal Proteins". PLOS Genetics. 1 (3): e35. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010035. PMC 1201370. PMID 16170411.

- Hunter, F. M.; Harcourt, R.; Wright, M.; Davis, L. S. (2000). "Strategic allocation of ejaculates by male Adelie penguins". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 267 (1452): 1541–1545. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1176. PMC 1690704. PMID 11007330.

- Rasotto, M.B; Shapiro, D. Y. (1998). "Morphology of gonoducts and male genital papilla, in the bluehead wrasse: implications and correlates on the control of gamete release". J. Fish Biol. 52 (4): 716–725. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb00815.x.

- Schöfl, G; Taborsky, Michael (2002). "Prolonged tandem formation in firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus) serves mate-guarding". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 52 (5): 426–433. doi:10.1007/s00265-002-0524-9. S2CID 19526835.

- Plath, Martin; Richter, Stephanie; Tiedemann, Ralph; Schlupp, Ingo (2008). "Male Fish Deceive Competitors about Mating Preferences". Current Biology. 18 (15): 1138–1141. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.067. PMID 18674912. S2CID 16611113.

- Fox, Stanley; McCoy, Kelly; Baird, Troy (2003). Lizard Social Behavior. p. 49.

- Birkhead, T.R.; Martinez, J. G.; Burke, T.; Froman, D. P. (1999). "Sperm mobility determines the outcome of sperm competition in the domestic fowl". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 266 (1430): 1759–1764. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0843. PMC 1690205. PMID 10577160.

- Hosken, D. J.; Garner, T. W. J.; Tregenza, T.; Wedell, N.; Ward, P. I. (2003). "Superior sperm competitors sire higher-quality young" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1527): 1933–1938. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2443. PMC 1691464. PMID 14561307.

- Searcy, W.A.; Andersson, Malte (1986). "Sexual selection and the evolution of song". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 17: 507–533. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.17.110186.002451. JSTOR 2097007.

- Hendrichs, J., Cooley, S. S., and Prokopy, R. J. (1992). Post-feeding bubbling behaviour in fluidfeeding Diptera: Concentration of crop contents by oral evaporation. Physiol. Entomol. 17: 153-161.

- Yuval, B.; Kaspi, R.; Field, S. A.; Blay, S.; Taylor, P. (2002). "Effects of Post-Teneral Nutrition on Reproductive Success of Male Mediterranean Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae)". Florida Entomologist. 85: 165–170. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0165:EOPTNO]2.0.CO;2.

- Bunning, H; Rapkin, J; Belcher, L; Archer, CR; Jensen, K; Hunt, J (2015). "Protein and carbohydrate intake influence sperm number and male fertility in male cockroaches but not sperm viability". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 282 (1802): 20142144. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2144. PMC 4344140. PMID 25608881.

- Parker, G. A. "Sperm competition and the evolution of animal mating strategies." Sperm competition and the evolution of animal mating systems (1984): 1-60.

- Birkhead, T.R (2000). "Defining and demonstrating postcopulatory female choice". Evolution. 54 (3): 1057–1060. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2000)054[1057:dadpfc]2.3.co;2. PMID 10937281. S2CID 6261882.

- Shackelford, T.K; Goetz, Aaron T. (2007). "Adaptation to sperm competition in humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16: 47–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x. S2CID 6179167.

- Gallup, G.G.; Burch, R.L.; Zappieri, M.L.; Parvez, R.A.; Stockwell, M.L.; Davis, J.A. "The human penis as a semen displacement device". Evolution and Human Behavior.

- Susan M. Block, Ph.D. (June 2, 2015). "Cuckold" (PDF). Wiley-Blackwell, International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- Schulte-Hostedde, AI; Millar, John S. (2004). "Intraspecific variation of testis size and sperm length in the yellow-pine chipmunk". Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 55 (3): 272–277. doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0707-z. S2CID 25202442.

- Fitzpatrick, John; Montgomerie, Robert; Desjardins, Julie; Stiver, Kelly; Kolm, Niclas; Balshine, Sigal (January 2009). "Female promiscuity promotes the evolution of faster sperm in cichlid fishes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (4): 1128–1132. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809990106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2633556. PMID 19164576.

- Fromhage, L (2006). "Emasculation to plug up females: the significance of pedipalp damage in Nephila fenestrata". Behav. Ecol. 17 (3): 353–357. doi:10.1093/beheco/arj037.

- Christenson, T.E (1989). "Sperm depletion in the golden orb-weaving spider, Nephila clavipes". J. Arachnol. 17: 115–118.

- Kempenaers, B (1999). "Extra-pair paternity and egg hatchability in tree swallows: evidence for the genetic compatibility hypothesis". Behavioral Ecology. 10 (3): 304–311. doi:10.1093/beheco/10.3.304.

- Charlesworth D, Willis JH (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483. S2CID 771357.

- Bernstein H, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1987). "The molecular basis of the evolution of sex". Molecular Genetics of Development. pp. 323–70. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 9780120176243. PMID 3324702.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Fitzpatrick JL, Evans JP (2014). "Postcopulatory inbreeding avoidance in guppies" (PDF). J. Evol. Biol. 27 (12): 2585–94. doi:10.1111/jeb.12545. PMID 25387854. S2CID 934203.

- Firman RC, Simmons LW (2015). "Gametic interactions promote inbreeding avoidance in house mice". Ecol. Lett. 18 (9): 937–43. doi:10.1111/ele.12471. PMID 26154782.

- Mack PD, Hammock BA, Promislow DE (2002). "Sperm competitive ability and genetic relatedness in Drosophila melanogaster: similarity breeds contempt". Evolution. 56 (9): 1789–95. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00192.x. PMID 12389723. S2CID 2140754.

- Simmons LW, Beveridge M, Wedell N, Tregenza T (2006). "Postcopulatory inbreeding avoidance by female crickets only revealed by molecular markers". Mol. Ecol. 15 (12): 3817–24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03035.x. PMID 17032276. S2CID 23022844.

- Snook, R (2005). "Sperm in competition: not playing by the numbers". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.011. PMID 16701340.

- Pitnick, S, Markow, T, & Spicer, G. (1999). "Evolution of multiple kinds of female sperm-storage organs in Drosophila" (PDF). Evolution. 53 (6): 1804–1822. doi:10.2307/2640442. JSTOR 2640442. PMID 28565462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pai, Aditi; Bernasconi, Giorgina (2008). "Polyandry and female control: the red flour beetleTribolium castaneum as a case study" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 310B (2): 148–159. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21164. PMID 17358014.

- Weigensberg, I; D.J. Fairbairn (1994). "Conflicts of interest between the sexes: a study of mating interactions in a semiaquatic bug". Animal Behaviour. 48 (4): 893–901. doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1314. S2CID 53199207.

- Moore, Harry; Dvoráková, Katerina; Jenkins, Nicholas; Breed, William (2002). "Exceptional sperm cooperation in the wood mouse" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 174–177. doi:10.1038/nature00832. PMID 12110888. S2CID 4413444.

- Firman, R. C.; Cheam, L. Y.; Simmons, L. W. (2011). "Sperm competition does not influence sperm hook morphology in selection lines of house mice". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (4): 856–862. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02219.x. PMID 21306461. S2CID 205433208.

- Harcourt, A.H., Harvey, P.H., Larson, S.G., & Short, R.V. 1981. Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates, Nature 293: 55-57

- Low, Bobbi S. (2007). "Ecological and socio-cultural impacts on mating and marriage". In R.I.M. Dunbar & L. Burnett (ed.). Oxford handbook of evolutionary psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 449–462. ISBN 978-0198568308.

- Birkhead, T.R.; Hunter, F.M. (1990). "Mechanisms of sperm competition" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 5 (2): 48–52. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(90)90047-H. PMID 21232320. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-17. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- Alcock 1998

- Barrie Heather & Hugh Robertson (2005). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand (Revised ed.). Auckland: Viking. ISBN 978-0143020400.

- Otronen, M.; Siva-Jothy, M. T. (1991-08-01). "The effect of postcopulatory male behaviour on ejaculate distribution within the female sperm storage organs of the fly, Dryomyza anilis (Diptera : Dryomyzidae)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (1): 33–37. doi:10.1007/BF00164292. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 38711170.

- Moore, HD; Martin, M; Birkhead, TR (1999). "No evidence for killer sperm or other selective interactions between human spermatozoa in ejaculates of different males in vitro". Proc Biol Sci. 266 (1436): 2343–2350. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0929. PMC 1690463. PMID 10643078.

- Swallow, John G; Wilkinson, Gerald S. (2002). "The long and short of sperm polymorphisms in insects" (PDF). Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 77 (2): 153–182. doi:10.1017/S1464793101005851. PMID 12056745. S2CID 14169522.

- Buckland-Nicks, John (1998). "Prosobranch parasperm: Sterile germ cells that promote paternity?". Micron. 29 (4): 267–280. doi:10.1016/S0968-4328(97)00064-4.

- Boulton, Rebecca A.; Cook, Nicola; Green, Jade; (Ginny) Greenway, Elisabeth V.; Shuker, David M. (13 January 2018). "Sperm blocking is not a male adaptation to sperm competition in a parasitoid wasp". Behavioral Ecology. 29 (1): 253–263. doi:10.1093/beheco/arx156.

- Dowling, D. K.; Nowostawski, A. Larkeson; Arnqvist, G. (2007). "Effects of cytoplasmic genes on sperm viability and sperm morphology in a seed beetle: implications for sperm competition theory?". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 20 (1): 358–368. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01189.x. PMID 17210029. S2CID 11987808.

Further reading

- Alcock, John 1998. Animal Behavior. Sixth Edition. 429–519.

- Eberhard, William 1996 Female Control: Sexual Selection by Cryptic Female Choice ISBN 0-691-01084-6

- Freeman, Scott; Herron, Jon C.; (2007). Evolutionary Analysis (4th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0-13-227584-8.

- Olsson, M.; Madsen, T.; Shine, R. (1997). "Is sperm really so cheap? Costs of reproduction in male adders, Vipera berus". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 264 (1380): 455–459. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0065. PMC 1688262.

- Ryan, Christopher & Jethá, Calcilda. Sex at Dawn: The prehistoric origins of modern sexuality. New York: Harper, 2010.

- Shackelford, T. K. & Pound, N. 2005. Sperm Competition in Humans : Classic and Contemporary Readings ISBN 0-387-28036-7.

- Shackelford, T. K.; Pound, N.; Goetz, A. T. (2005). "Psychological and physiological adaptations to sperm competition in humans" (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 9 (3): 228–248. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.228. S2CID 37941662.

- Simmons, Leigh W. 2001. Sperm competition and its evolutionary consequences in the insects. Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05988-8 and ISBN 0-691-05987-X

- Singh, S R; Singh, Bashisth N.; Hoenigsberg, Hugo F. (2002). "Female remating, sperm competition and sexual selection in Drosophila" (PDF). Genet. Mol. Res. 1 (3): 178–215. PMID 14963827. S2CID 36236503. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-08.

- Snook, Rhonda R. Postcopulatory reproductive strategies. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences http://www.els.net Archived 2011-05-13 at the Wayback Machine