Kassian Cephas

Kassian Cephas or Kassian Céphas (15 January 1845 – 16 November 1912) was a Javanese photographer of the court of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. He was the first indigenous person from Indonesia to become a professional photographer and was trained at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwana VI (r. 1855–1877). After becoming a court photographer in as early 1871, he began working on portrait photography for members of the royal family, as well as documentary work for the Dutch Archaeological Union (Archaeologische Vereeniging). Cephas was recognized for his contributions to preserving Java's cultural heritage through membership in the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies and an honorary gold medal of the Order of Orange-Nassau. Cephas and his wife Dina Rakijah raised four children. Their eldest son Sem Cephas continued the family's photography business until his own death in 1918.

Kassian Cephas | |

|---|---|

Kassian Cephas wearing the honorary gold medal of the Order of Orange-Nassau (c. 1905) | |

| Born | Kassian 15 January 1845 |

| Died | 16 November 1912 (aged 67) |

| Known for | Photography |

Early life

Kassian Cephas was born in Yogyakarta to the Javanese couple of Kartodrono and Minah.[1] As a youth, Cephas became a pupil of Protestant Christian missionary Christina Petronella Philips-Steven and followed her to nearby Bagelen, Purworejo. He was baptized there on 27 December 1860 at the age of fifteen and took the name of Cephas, the Aramaic equivalent of Saint Peter's name, as his baptismal name. He began using Cephas as a family name following the baptism.[2]

Photography career

Upon Cephas' return to Yogyakarta in the early 1860s, he began training under Simon Willem Camerik, a member of the civil militia and court photographer of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. Cephas' training was conducted at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwana VI, who noted his talent for photography. He became the appointed court painter and photographer as early as 1871.[3]

Cephas' studio was located on the second floor of the building where he and his wife lived in Yogyakarta's Lodji Ketjil Wetan area, now known as Major Suryotomo Street. His photography business was not the only one established in the area during this time period.[4] Aside from portrait photography, Cephas also produced many works on buildings and ancient monuments. This included photographs of the Taman Sari Water Castle (1884) for the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences.[5]

Professional works

His work first appeared for a wider public in 1888 in the publication In den Kedaton te Jogjåkartå by Isaäc Groneman. The book included 16 collotype prints of the art of Hindu Javanese dances. Groneman wished to generate interest in this culture in the Netherlands and requested permission from Sultan Hamengkubuwana VII for Cephas to photograph the dance scenes. The publication was originally prepared by the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, but the high cost of collotype prints forced the institute to abandon it. In keeping with the technological advances of photography, Cephas bought a new camera in 1886 which enabled him to capture pictures in 1/400th of a second. This allowed the subjects to be photographed more quickly rather than having to remain still for several moments.[6] These pictures were often presented as farewell presents to European elites when they left Yogyakarta to return to Europe and to Dutch civil servants.[7]

In 1889, the Archaeological Union (Archaeologische Vereeniging) began efforts to study and preserve monuments of the Hindu Javanese civilization in Central Java. One of the locations having high priority in the union's efforts was the temple of Prambanan, part of the larger complex attributed to the legend of Loro Jonggrang. Cephas was assigned to photograph the site, while his eldest son Sem drew the buildings' profiles and ground plans. Groneman submitted the photographs and descriptions made by Cephas to the Royal Institute in 1891, but it would not be published until 1893 because of the high reproduction costs. The final publication included 62 collotypes depicting Prambanan and the surrounding temples.[7]

Cephas was also credited with photographing the Borobudur temple complex after its hidden base was discovered in 1885 by the union's first chairman. The base was briefly uncovered in 1890 to be photographed and then covered again in 1891. Because Cephas only received one-third of the original subsidy from the government, he was not able to complete the 300 photographs calculated to be needed for the project. Each photographic plate would have required one-half hour to develop with the dry gelatin process for a total of 150 hours. In all, only 160 segments of the base's reliefs were photographed, and an additional four photographs were made to provide a general overview for the site. The series was published 30 years later by the Royal Institute in a collotype collection.[7]

International recognition

Following the completion of the Borobudur project, Cephas was appointed as an "extraordinary member" of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences for his works as a "photographer and practitioner of Indies archaeology".[8] Several years later, he was nominated for membership in the Royal Institute in recognition of his work with the Archaeological Union. Cephas accepted the nomination in a letter dated 15 June 1896. Later that year, he photographed a visit by Thailand's King Chulalongkorn to Yogyakarta.[9] As a token of gratitude, the king presented him with a case of three jeweled buttons.[10]

Groneman and Cephas worked together for the final time in 1899 to document the four-year commemoration of Hamengkunegara III's accession to the throne as Crown Prince of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. The event's preparation took one and a half years, and a theatrical performance lasting four days was attended by 23,000 to 36,000 spectators daily. A blue velvet book covered with gold and diamonds covering the performance was presented as a gift on the occasion of the wedding of Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Henry of the Netherlands in 1901. On the occasion of Wilhelmina's 21st birthday later that year, Cephas was awarded with an honorary gold medal of the Order of Orange-Nassau for his work to portray and preserve Java's cultural heritage.[10]

Death and legacy

Cephas retired from photography around the age of 60. Just over a year after the 16 September 1911 death of his wife, he died at the age of 67 due to illness. The family's photography business ended several years later when Sem Cephas died on 20 March 1918 in a horseriding accident. They were all buried in Yogyakarta between the Beringharjo market and the Lodji Ketjil area.[11] Their graves were moved to Sasanalaya Cemetery, east of Brigadier General Katamso Street, in 1964, to make way for new buildings.[12] Although both Cephas and his son were accomplished court photographers, Cephas was the most important of the two and was the first Javanese person (and therefore first indigenous Indonesian) to become a professional photographer.[13]

Personal life

Cephas married Dina Rakijah (b. 1846), a Christian Javanese woman and daughter of Soerobangso and Rad Rakemah, at a church in Yogyakarta on 22 January 1866.[2] The couple raised one daughter and three sons: Naomi (b. 28 June 1866), Sem (b. 15 March 1870), Fares (b. 30 January 1872), and Jozef (b. 4 July 1881). They also had a son named Jacob who was born in 1868, but died the same year. Naomi married Dutch engineer Christiaan Beem in 1882, and the couple had thirteen children, eight of whom reached adulthood. Cephas' eldest son Sem became a photographer and painter in his father's studio.[4]

Gallery

Hamengkoe Boewono VII, sultan of Yogyakarta, 1885

Hamengkoe Boewono VII, sultan of Yogyakarta, 1885 Pangeran Aria Boeminata, brother of sultan Hamengkoe Boewono VII

Pangeran Aria Boeminata, brother of sultan Hamengkoe Boewono VII Ratoe Madoeretna, daughter of sultan Hamengkoe Boewono VII

Ratoe Madoeretna, daughter of sultan Hamengkoe Boewono VII Sultan Hamengkoe Buwono VII walks with arms linked with the Dutch resident (governor) of Yogyakarta, C. M. Ketting Olivier. Garebeg, anniversary of the prophet Mohammed, around 1894

Sultan Hamengkoe Buwono VII walks with arms linked with the Dutch resident (governor) of Yogyakarta, C. M. Ketting Olivier. Garebeg, anniversary of the prophet Mohammed, around 1894 Lodjie Ketjilstreet, Yokyakarta

Lodjie Ketjilstreet, Yokyakarta Wajang kulit show accompanied by a gamelan orchestra

Wajang kulit show accompanied by a gamelan orchestra Javanese dancer in court costume, studio around 1890

Javanese dancer in court costume, studio around 1890 Court dancers performing a serimpi

Court dancers performing a serimpi Pusaka (heirloom) of the court of Yogyakarta

Pusaka (heirloom) of the court of Yogyakarta Pajoen (umbrella) from the kraton of Yogyakarta (coloured)

Pajoen (umbrella) from the kraton of Yogyakarta (coloured) Temple guard sculpture at the northern entrance of candi Sewu, Mid Java

Temple guard sculpture at the northern entrance of candi Sewu, Mid Java Prambanan temple complex, with temples for Brahma Shiva and Vishnu

Prambanan temple complex, with temples for Brahma Shiva and Vishnu Tjandi Mendoet temple, relief in the interior near the entrance

Tjandi Mendoet temple, relief in the interior near the entrance Borobudur Relief O 101

Borobudur Relief O 101 Borobudur Relief O 123

Borobudur Relief O 123 Borobudur Relief O 149

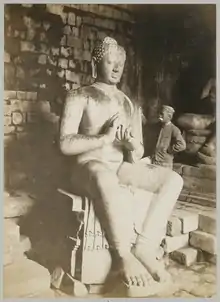

Borobudur Relief O 149 Céphas near the Buddha sculpture in Tjandi Mendoet

Céphas near the Buddha sculpture in Tjandi Mendoet

See also

- Isidore van Kinsbergen

- History of photography

- Tassilo Adam, court photographer for the VII Sultan

Notes

- Guillot (1981, p. 61) gives 15 February 1844 as Cephas' date of birth, citing his baptismal register. Knaap (1999, p. 5) argues that this date is incorrect as 15 January 1845 is written on his tombstone. The advertisement of his death in 1912 stated that he was 67 years old.

- Knaap 1999, p. 6

- Knaap 1999, p. 7

- Knaap 1999, p. 8

- Knaap 1999, p. 10

- Knaap 1999, p. 15

- Knaap 1999, p. 16

- Knaap 1999, p. 17

- Knaap 1999, p. 18

- Knaap 1999, p. 20

- Knaap 1999, pp. 21–22

- Knaap 1999, p. 23

- Knaap 1999, p. 1

References

- Guillot, Clude (1981), "Un exemple d'assimilation á Java: le photographe Kassian Céphas", Archipel (in French), 22: 55–73, doi:10.3406/arch.1981.1669, ISSN 0044-8613.

- Knaap, Gerrit (1999), Cephas, Yogyakarta: Photography in the Service of the Sultan, Leiden: Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, ISBN 978-90-6718-142-6.

- Soerjoatmodjo, Yudhi (1999), "The Transfixed Spectator: The World as a Stage in the Photographs of Kassian Cephas", in Knaap, Gerrit (ed.), Cephas, Yogyakarta: Photography in the Service of the Sultan, Leiden: Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, pp. 25–27, ISBN 978-90-6718-142-6.

External links

- Kassian Cephas: Pioneer photography from the Dutch Indies

- Kassian Cephas views of Java, 1872-1896, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Accession No. 2002.R.40. The collection comprises 18 albumen photographs of Indonesian Buddhist temples at Borobudur and Prambanam by Kassian Cephas.