Khecheopalri Lake

Khecheopalri Lake, originally known as Kha-Chot-Palri (meaning the heaven of Padmasambhava), is a lake located near Khecheopalri village, 147 kilometres (91 mi) west of Gangtok in the West Sikkim district of the Northeastern Indian state of Sikkim.[1]

| Khecheopalri Lake | |

|---|---|

Foot bridge approach to the Khecheolpalri Lake | |

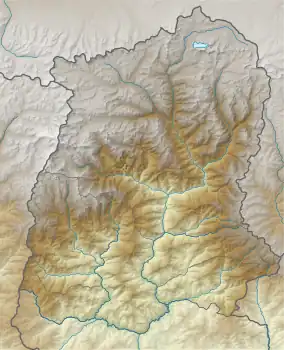

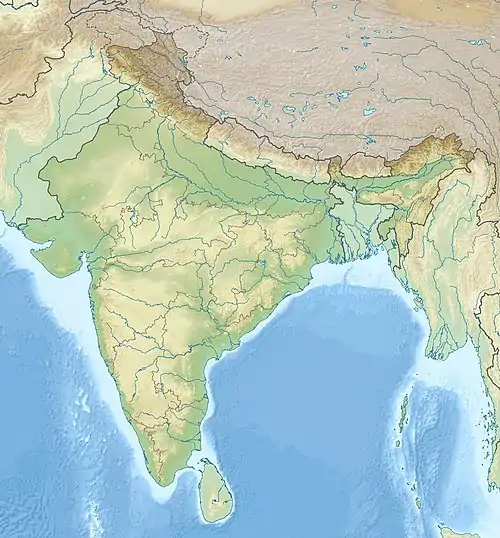

Khecheopalri Lake Location in Sikkim  Khecheopalri Lake Khecheopalri Lake (India) | |

| Location | Sikkim |

| Coordinates | 27.3500°N 88.1886°E |

| Lake type | Sacred |

| Primary inflows | Two perennial and five seasonal stream inlets |

| Primary outflows | One outlet |

| Catchment area | 12 km2 (4.6 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | India |

| Surface area | 3.79 hectares (9.4 acres) |

| Average depth | 7.2 m (24 ft) |

| Max. depth | 11.2 m (37 ft) |

| Water volume | 272,880 cubic metres (9,637,000 cu ft) |

| Surface elevation | 1,700 m (5,600 ft) |

| Islands | None |

| Settlements | Khecheopalri village, Yuksom and Geyzing |

Located 34 kilometres (21 mi) to the northwest of Pelling town, the lake is sacred for both Buddhists and Hindus, and is believed to be a wish fulfilling lake. The local name for the lake is Sho Dzo Sho, which means "Oh Lady, Sit Here". The popularly known name of the lake, considering its location is Khecheopalri Lake, ensconced in the midst of the Khechoedpaldri hill, which is also considered a sacred hill.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

The lake is an integral part of the much revered valley of "Demazong" meaning valley of rice. This landscape is also known as a land of hidden treasures blessed by Guru Padmasambhava.[2]

The Khecheopalri Lake is also part of Buddhist religious pilgrimage circuit involving the Yuksom, the Dubdi Monastery in Yuksom, Pemayangtse Monastery, the Rabdentse ruins, the Sanga Choeling Monastery, and the Tashiding Monastery.[2][8] An interesting feature of the lake is that leaves are not allowed to float on the lake, which is ensured by the birds which industriously pick them up as soon as they drop into the lake surface.[5][7]

The Khecheopalri Lake and the Khangchendzonga National Park are conserved from the biodiversity perspective with ecotourism and pilgrimage as essential offshoots. [1] As a result, their recreational and sacredness values are enhanced.[9]

Etymology

According to folklore morphometry, Khecheopalri is made up of two words, Kheecheo and palri. 'Khecheo' means "flying yoginis" or "Taras" (female manifestations of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion) and 'palri' means "palace".[2]

Legends

According to folklore legend related to Sikkim topography, the Khecheopalri is said to represent one of the four plexus of the human body namely, the thorax; the other three plexes are said to be represented by Yuksom (the third eye), Tashiding (head) and Pemayangtse (the heart).[2]

The mythological links to the origin of all the lakes in Sikkim make them sacred and so is the case with the Khecheopalri Lake. Many legends are narrated such as: Guru Padmasambahava preached to sixty-four yoginis here; it is the residing place of the Goddess Tara Jetsun Dolma and the Khecheopalri Lake is her footprint; the lake represents the Goddess Chho Pema; footprints of Macha Zemu Rinpoche are on a stone near the chorten (stupa) near the lake; Hindu god Shiva meditated in Dupukney Cave that is situated above the lake and hence worshipped on "Nag Panchami" day at the lake; a Lepcha girl named Nenjo Asha Lham was blessed by the lake goddess and was gifted with a precious gem which was lost, and it is the belief of the local people that the gem is hidden in the lake; the lake water has curative properties and hence permitted to be used only for performing rites and rituals; and with all these legends, the lake is called a "wish fulfilling lake".[2][10]

Another folk legend narrated (a plaque erected at the entrance to the lake by the Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs, Government of Sikkim gives some details of the legend[11]) is that long time back this place used to be a grazing ground, troubled by nettle (the native original tribal population make use of the barks of nettle for multipurpose uses). Then, on a particular day, a Lepcha couple were peeling off the bark of the nettle when they saw a pair of conch shells falling from air on the ground. This was followed by severe shaking of the ground and spring water emerged from below and thus the lake was formed. Based on the sacred Nesol text, the lake was interpreted as the abode of "Tshomen Gyalmo or chief protective nymph of the Dharma as blessed by Goddess Tara".[11]

This lake was also identified as the footprints of Goddess Tara, as from a high vantage point the contours of the lake appear like a footprint. Another belief is that the foot prints are of Hindu god Shiva.[2] The lake because of its high religious significance has been declared a protected lake under the Govt. of Sikkim Notification no. 701/Home/2001/dated 20-09-2001 and the provision of the place of worship (Special Provision Act 1991 of Government of India. Department of Eccliastical Affairs, Government of Sikkim.[11]

The sanctity of the lake is exemplified by another legend, which says that the shape of the lake is in the form of foot that represents the foot of Buddha, which could be seen from the surrounding hills.[6]

Topography

The lake was the original névé (term used to define formation of a glacier from compact granular snow) region of ancient precipitous glaciers. The depression where the lake is situated was formed by the scooping action of the glacier. It forms the southern bank of the Lethang valley. The formation of the lake is estimated to be 3500 years old.[2] The lake is situated amidst pristine forest at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,600 ft) near Tsozo village.[2] The lake drains a catchment area of the Ramam watershed (Ramam mountain gives its name to the valley) and has a drainage area of 12 square kilometres (4.6 sq mi) (including area of bog of 70,100 square metres (755,000 sq ft). The periphery of lake has the shape of a foot. The surface water spread area of the lake is 3.79 hectares (9.4 acres). The depth of water in the lake varies from 3.2–11.2 metres (10–37 ft) with an average depth of 7.2 metres (24 ft).[2] It is also inferred from a visual observation of the lake that it has undergone changes in its size due to encroachment due to peripheral vegetation and eutrophication, and its original size could have been three times of its present size. The lake's water spread, which was 7.4 hectares (18 acres) in 1963 reduced to 3.8 hectares (9.4 acres) in 1997 and consequently the peatland (bog) increased from 3.4–7 hectares (8.4–17.3 acres). Inflow into the lake is through two perennial and five non perennial streams, while the outflow is from one outlet. In addition, during the monsoon season two streams are also diverted temporarily into the lake to supplement its storage capacity. The geological setting in the lake and its surrounding hills consist of granite gneiss, schist and phyllites.[2][3][9]

The lake is enveloped in a dense forest cover of temperate vegetation and bamboo. 72 households and 440 people live in villages around the lake periphery. The Lepchas are the main ethnic group of the place. Traditional agriculture is the main livelihood and recently some households have become involved in tourism.[9] Pelling–Yuksom road leads to the lake, which is surrounded by densely forested hills. There is also a monastery above the lake.

Climate

The climate of the lake region is monsoonal. The maximum and minimum temperatures recorded are 24 °C (75 °F) and 4 °C (39 °F).

Flora and fauna

- Vegetation

The lake is surrounded by a broad-leaved mixed temperate forest.[9] However, the vegetation in the lake comprises Macrophytes, Phytoplankton and Zooplankton.[1]

The Phytoplankton species are a composition of different families namely, Chlorophyceae (18) which is the foremost group, Chrysophyceae (15), Cyanophyceae (11), and one species each of Charophyceae, Euglenophyceae, Dinophyceae and Cryptophyceae.[1]

The Zooplanktons recorded are: 7 rotifers, 5 protozoans, 2 each of copepods and cladocerans, and 1 each of ostracods and isopods.[3]

- Aquatic fauna

The fish species recorded in the lake are: Cyprinus carpio, Danio aequipinnatus, Garra sp., Schistura sp. and Schziothorax sp.[1]

- Avifauna

The avifauna recorded in the lake, particularly in the festive season when they gather in the early hours of the morning (dispersed with human presence) at the middle of the lake are: grebe (Podiceps ruficollis), common merganser– Mergus merganser, large cormorant (phalacrocorax carbo), little cormorant (microcarbo niger), common teal (Anascrecca), tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), White-breasted waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus), moorhen (gallimlachorophy) and crane brown Amaurornisbi colour. The lake is also a resting-place for Trans-Himalayan migratory birds and supports commercial and recreational tourism.[9] Trans Himalayan migratory birds visit the lake.[2]

Threats

Khecheopalri Lake and the Khangchendzonga National Park (KNP), which are visited by tourists and trekkers on the Yuksom-Dzongri-GoechhaLa trekking corridor (45 kilometres (28 mi) long trek) have caused concerns of environmental deterioration in the region. It is recorded that tourist inflow into Sikkim had seen a quantum jump in the period between 1980 and 2001; domestic tourism increased by more than 10 times and international tourists inflow increased by about fourfold. This concern is not limited to very high influx of tourists but also loss of biodiversity due to extraction of valuable ecosystem components due to deforestation and adoption of harmful land-use practices. The inhabitants around the lake exploit the natural resources of the lake watershed by way of extraction of fuel, fodder and timber, and by livestock grazing.[9] Pilgrimage season compounds the threats to the lake environment in the form of outwash of the offerings made into the lake by pilgrims, decomposition of waste material resulting in increase in acidity of the lake waters and consequent high pH values (varied between 6.8 and 8.5), reduction in Dissolved Oxygen levels, increase in concentration of chlorides, iron and ammonia levels and proliferation of planktons such as protococus and tetraspora. All these factors increased the pollution level in the lake waters.

Conservation measures

A scientific study was, therefore, instituted (the first such study in India of a sacred lake in a temperate zone) with the objective of quantifying the sacredness value of the lake and the related recreational value of the Yuksom-Dzongri-Goechha La corridor. The study was carried out by gathering interactive information from tourists who visit the lake throughout the year (both national and international) and local community on their perceptions for conservation and tourism. This study has established that monetary values need to be attributed to conservation of the site for biodiversity and pilgrimage through regulated ecotourism. This could also usher in economic development, closely linked to conservation.[2][9]

Thus, ecotourism, promoted with the involvement of local communities, could not only provide economic benefits but also control further deterioration of biodiversity in the Khecheopalri Lake surroundings as well as in the Yuksom-Dzongri-Goechha La Corridor. Further, as a conservation measure, fishing or any other recreational activities at the lake have been prohibited. Swimming and boating in the lake are also prohibited. There is also the belief among the local community that any disturbance on the 'Holy Lake' could lead to calamities and unwelcome events.[2][9]

To reduce the pollution levels in the lake, the measures envisaged are: afforestation of degraded forest areas, prayer ceremonies to be made monastery centric than lake centric, implement a management plan with full local participation, shifting cultivation and grazing in the catchment to be discouraged, weed control through manual and mechanical extraction and most importantly to check anthropogenic and agricultural runoff into the lake.

To ensure lake conservation and management, the Khecheopalri Holy Lake Welfare Committee (KHLWC) and the local community are involved in developing plantations and management of festivals. They have stopped grazing around the lake periphery and even stopped construction of a footpath on the periphery of the lake in order to maintain the forest vegetation surrounding the lake.[12]

Facilities

Now, there is a lake Jetty that leads to the front of the lake and from where prayers and incense are offered. Prayer wheels are fixed along the jetty with prayer flags and Tibetan inscriptions, adding to the piety of the place.[5]

Annual Buddhist rituals from the readings of the Naysul prayer book, which describes the origin of Sikkim and has several tantric secret prayers, are chanted at the lake.

Religiosity

The placid waters of the lake are visited by many pilgrims and tourists. From the main gate, where there are small shops and road ends to the lake is about a ten to fifteen minutes walk through a lovely tropical forest.

Festival

As the sacred Khecheopalri Lake is known as a "wish fulfilling lake", folklore and legends associated with it are many. The folk lore has generated deep religious interest and as a result lake's waters are permitted to be used only for performing rites and rituals. Consequently, a religious fair, one of the largest festivals, is held here every year for two days in Maghe purne (March/April), which is attended by a large number of pilgrims from all parts of Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal and India. They offer food material to the lake and carry waters of the lake as Prasad (substance that is first offered to a deity and then consumed). People believe that Shiva exists in "solemn meditation inside the lake".[9] During this festival, pilgrims float butter lamps in the lake on bamboo boats tied with khadas (scared scarves), in the evenings chanting prayers as mark of reverence, along with many other food offerings.[5][6]

Chho-Tsho, is another festival that is observed here in the month of October after the cardamom harvest to offer gratitude for providing people with food.

See also

Gallery

Another view of Khecheolpalri Lake

Another view of Khecheolpalri Lake A plaque at entrance to Khecheolpalri Lake

A plaque at entrance to Khecheolpalri Lake Prayer flags at Khecheolpalri Lake

Prayer flags at Khecheolpalri Lake A small shrine at Khecheolpalri Lake

A small shrine at Khecheolpalri Lake

References

- O'Neill, Alexander; et al. (25 February 2020). "Establishing Ecological Baselines Around a Temperate Himalayan Peatland". Wetlands Ecology & Management. 28 (2): 375–388. doi:10.1007/s11273-020-09710-7. S2CID 211081106.

- Jain, Alka; H. Birkumar Singh; S. C. Rai; E. Sharma (2004). "Folklores of Sacred Khecheopalri Lake in the Sikkim Himalaya of India: A Plea for Conservation". Asian Folklore Studies. Nanzan University. 63. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- "Wetland Inventory" (PDF). Sacred Khechopalri Lake. Envis: National Informatics Centre. p. 369. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Silas, Sandeep (2005). Discover India by Rail. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 81-207-2939-0. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Bindloss, Joe; Sarina Singh (2007). India. Lonely Planet. pp. 585. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

Yuksom.

- Bradnock, Roma (2004). Footprint India. Footprint Travel Guides. p. 634. ISBN 1-904777-00-7. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- "West Sikkim". Sikkim Online. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Choudhury, Maitreyee (2006). Sikkim: Geographical Perspects. Mittal Publications. pp. 80–81. ISBN 81-8324-158-1. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Our View". Brief Overview of Valuation of Ecotourlsm in the S1kkim Himalaya. Environment Centre on Ecotourism in Sikkim: national Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Evershed, Sarah; Guru Tashi (2012). "In the Middle of the Lotus: Khecheopalri Lake, A Contested Sacred Land in the Eastern Himalaya of Sikkim" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Institute of Ecology (17): 11. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- File:A plaque at entrance to Khecheolpalri Lake.jpg: Official plaque at entrance to Khecheolpalri Lake erected by the Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs, Government of Sikkim.

- Thakur, Baleshwar; V.N.P. Sinha; M. Prasad; Rana Pratap (2005). Urban and regional development in India: essays in honour of Prof. L.N. Ram. Concept Publishing Company. p. 417. ISBN 81-8069-199-3. Retrieved 7 May 2010.