Isin

Isin (Sumerian: 𒉌𒋛𒅔𒆠, romanized: I3-si-inki,[1] modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. Excavations have shown that it was an important city-state in the past.

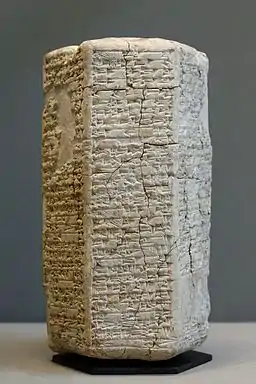

.jpg.webp) Left: Cuneiform clay tablet. Old Babylonian, 1900-1700 BCE. Right: Sumerian cuneiform "foundation stone". This clay cone was embedded in a wall, and contains the deed of foundation of the city walls of Isin (Tell Bahriyat) by king Ishme-Dagan of Isin (1953-1935 BCE). | |

Shown within Iraq | |

| Alternative name | Ishan al-Bahriyat |

|---|---|

| Location | Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°53′06″N 45°16′07″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Dynastic, Isin-Larsa, Old Babylonian, Kassite |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1924, 1973-1989 |

| Archaeologists | Stephen Herbert Langdon, Barthel Hrouda |

History of archaeological research

Ishan al-Bahriyat was visited by Stephen Herbert Langdon for a day to conduct a sounding, while he was excavating at Kish in 1924.[2] Most of the major archaeological work at Isin was accomplished in 11 seasons between 1973 and 1989 by a team of German archaeologists led by Barthel Hrouda.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] However, as was the case at many sites in Iraq, research was interrupted by the Gulf War (1990-1) and the Iraq War (2003 to 2011). Since the end of excavations, extensive looting is reported to have occurred at the site. Even when the German team began their work, the site had already been heavily looted.

Isin and its environment

Isin is located approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of Nippur. It is a tell, or settlement mound, about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) across and with a maximum height of 8 metres (26 ft).

History

The site of Isin was occupied at least as early as the Early Dynastic period in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, and possibly as far back as the Ubaid period. While cuneiform tablets from that time were found, the first epigraphic reference to Isin was not until the Ur III period.

When the deteriorating Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III) finally collapsed at the hands of the Elamites at the end of the third millennium BC, a power vacuum was left that other city-states scrambled to fill. The last king of the Ur Dynasty, Ibbi-Sin, had not the resources nor the organized government needed to expel the Elamite invaders. One of his governmental officials, Ishbi-Erra, relocated from Ur to Isin, another city in the south of Mesopotamia, and established himself as a ruler there. One of Ishbi-Erra's year names reports his defeating Ibbi-Sin in battle.[11]

Although he is not considered part of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Ishbi-Erra did make some attempts at continuing the trappings of that dynasty, most likely to justify his rule.[11] Ishbi-Erra had ill luck expanding his kingdom, however, for other city-states in Mesopotamia rose to power as well. Eshnunna and Ashur were developing into powerful centers. However, he did succeed in repulsing the Elamites from the Ur region. This gave the Isin dynasty control over the culturally significant cities of Ur, Uruk, and the spiritual center of Nippur.

For over 100 years, Isin flourished. Remains of large buildings projects, such as temples, have been excavated. Many royal edicts and law-codes from that period have been discovered. The centralized political structure of Ur-III was largely continued, with Isin's rulers appointing governors and other local officials to carry out their will in the provinces. Lucrative trade routes to the Persian Gulf remained a crucial source of income for Isin.

The exact events surrounding Isin's disintegration as a kingdom are mostly unknown, but some evidence can be pieced together. Documents indicate that access to water sources presented a huge problem for Isin. Isin also endured an internal coup of a sort when Gungunum the royally appointed governor of Larsa and Lagash province, seized the city of Ur. Ur had been the main center of the Gulf trade; thus this move economically devastated Isin. Additionally, Gungunum's two successors Abisare and Sumuel (c. 1905 BC and 1894 BC) both sought to cut Isin off from its canals by rerouting them into Larsa. At some point, Nippur was also lost. Isin would never recover. Around 1860 BC, an outsider named Enlil-bani seized the throne of Isin, ending the hereditary dynasty established by Ishbi-Erra over 150 years earlier. [12]

Although politically and economically weak, Isin maintained its independence from Larsa for at least another forty years, ultimately succumbing to Larsa's ruler Rim-Sin I.

After the First Dynasty of Babylon rose to power in the early 2nd millennium and captured Larsa, much significant construction occurred at Isin. This ended with a destruction dated to around the 27th year of the reign of Samsu-iluna, son of Hammurabi, based on tablets found there.

Later, the Kassites who took over in Babylon after its sack in 1531 BC, resumed building at Isin. The final significant stage of activity occurred during the Second Dynasty of Isin at the end of the 2nd millennium, most notably by king Adad-apla-iddina.

Of the at least 256 ruler year names about 75% have been found. Most have the standard format, aside from Bur-Sin who numbered his years. These year names combined with new tablet joins show that there were two additional rulers, Sumu-abum and Ikūn-pī-Išta, slotting in between Erra-imittī and Enlil-bān. The reign of Sumu-abum lasted less than a year.[13]

Isin-Larsa period (c. 2025 – c. 1763 BC)

First dynasty of Isin (c. 2018 – c. 1792 BC)

.jpg.webp)

| Ruler | Reigned (Short Chronology) | Reigned (Middle Chronology) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ishbi-Erra | c. 1953 – c. 1920 BC | c. 2018 – c. 1985 BC | Contemporary of Ibbi-Suen of Ur III |

| Shu-Ilishu | c. 1920 – c. 1911 BC | c. 1985 – c. 1975 BC | Son of Ishbi-Erra |

| Iddin-Dagan | c. 1911 – c. 1890 BC | c. 1975 – c. 1954 BC | Son of Shu-ilishu |

| Ishme-Dagan | c. 1890 – c. 1871 BC | c. 1954 – c. 1934 BC | Son of Iddin-Dagan |

| Lipit-Eshtar | c. 1871 – c. 1860 BC | c. 1934 – c. 1923 BC | Contemporary of Gungunum of Larsa |

| Ur-Ninurta | c. 1860 – c. 1832 BC | c. 1923 – c. 1895 BC | Contemporary of Abisare of Larsa |

| Bur-Suen | c. 1832 – c. 1811 BC | c. 1895 – c. 1874 BC | Son of Ur-Ninurta |

| Lipit-Enlil | c. 1811 – c. 1806 BC | c. 1874 – c. 1869 BC | Son of Bur-Suen |

| Erra-imitti | c. 1806 – c. 1799 BC | c. 1869 – c. 1861 BC | |

| Ikūn-pî-Ištar | c. 1799 – c. 1798 BC | c. 1861 – c. 1837 BC | |

| Enlil-bani | c. 1798 – c. 1775 BC | c. 1861 – c. 1837 BC | Contemporary of Sumu-la-El of Babylon |

| Zambiya | c. 1775 – c. 1772 BC | c. 1837 – c. 1834 BC | Contemporary of Sin-Iqisham of Larsa |

| Iter-pisha | c. 1772 – c. 1767 BC | c. 1834 – c. 1830 BC | |

| Ur-du-kuga | c. 1767 – c. 1764 BC | c. 1830 – c. 1826 BC | |

| Suen-magir | c. 1764 – c. 1753 BC | c. 1826 – c. 1815 BC | |

| Damiq-ilishu | c. 1753 – c. 1730 BC | c. 1815 – c. 1792 BC | Son of Suen-magir |

Dynasty of Larsa (c. 1792 – c. 1736 BC)

| Ruler | Reigned (Short Chronology) | Reigned (Middle Chronology) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rim-Sin I | c. 1730 – c. 1699 BC | c. 1792 – c. 1763 BC | |

| Rim-Sin II | c. 1678 – c. 1674 BC | c. 1741 – c. 1736 BC |

Old Babylonian period (c. 1763 – c. 1595 BC)

First dynasty of Babylon (c. 1736 – c. 1732 BC)

| Ruler | Reigned (Short Chronology) | Reigned (Middle Chronology) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Samsu-iluna | c. 1672 – c. 1668 BC | c. 1736 – c. 1732 BC |

First dynasty of Sealand (c. 1732 – c. 1475 BC)

| Ruler | Reigned (Short Chronology) | Reigned (Middle Chronology) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ilumael | c. 1700 BC | c. 1732 BC | |

| Itti-ili-nibi | c. 1700 BC | ||

| Unknown | c. 1683 BC | ||

| Damqi-ilishu | c. 1677 BC | ||

| Ishkibal | c. 1641 BC | ||

| Shushushi | c. 1616 BC | ||

| Gulkishar | c. 1589 BC | ||

| Gishen | c. 1580 BC | ||

| Peshgaldaramesh | c. 1550 BC | ||

| Ayadaragalama | c. 1545 – c. 1517 BC | ||

| Akurduana | c. 1517 – c. 1491 BC | ||

| Melamkurkurra | c. 1491 – c. 1484 BC | ||

| Ea-gamil | c. 1460 BC | c. 1484 – c. 1475 BC |

Middle Babylonian period (c. 1595 – c. 626 BC)

Second dynasty of Isin (c. 1153 – c. 1022 BC)

| Ruler | Reigned (Short Chronology) | Reigned (Middle Chronology) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marduk-kabit-ahheshu | c. 1153 – c. 1135 BC | ||

| Itti-Marduk-balatu | c. 1135 – c. 1129 BC | ||

| Ninurta-nadin-shumi | c. 1129 – c. 1122 BC | ||

| Nebuchadnezzar I | c. 1122 – c. 1100 BC | ||

| Enlil-nadin-apli | c. 1100 – c. 1096 BC | ||

| Marduk-nadin-ahhe | c. 1096 – c. 1078 BC | ||

| Marduk-shapik-zeri | c. 1078 – c. 1065 BC | ||

| Adad-apla-iddina | c. 1065 – c. 1041 BC | ||

| Marduk-ahhe-eriba | c. 1041 BC | ||

| Marduk-zer-X | c. 1041 – c. 1029 BC | ||

| Nabu-shum-libur | c. 1029 – c. 1022 BC |

Culture and literature

The city lay on the Isinnitum Canal, part of a set of waterways that connected the cities of Mesopotamia. The patron deity of Isin was Nintinuga (Gula) goddess of healing, and a temple to her was built there. The Isin king Enlil-bani reported building a temple to Gula named E-ni-dub-bi, a temple for Sud named E-dim-gal-an-na, a temple E-ur-gi-ra to Ninisina, as well as a temple for the god Ninbgal.[12][14]

Ishbi-Erra continued many of the cultic practices that had flourished in the preceding Ur III period. He continued acting out the sacred marriage ritual each year. During this ritual, the king played the part of the mortal Dumuzi, and he had sex with a priestess who represented the goddess of love and war, Inanna (also known as Ishtar). This was thought to strengthen the king's relationship to the gods, which would then bring stability and prosperity on the entire country.

The Isin kings continued also the practice of appointing their daughters official priestesses of the moon god of Ur.

The literature of the period also continued in the line of the Ur III traditions when the Isin dynasty was first begun. For example, the royal hymn, a genre started in the preceding millennium, was continued. Many royal hymns written for the Isin rulers mirrored the themes, structure, and language of the Ur ones. Sometimes the hymns were written in the first person of a king's voice; other times, they were pleas of ordinary citizens meant for the ears of a king (sometimes an already dead one).

It was during this period that the Sumerian King List attained its final form, though it used many much earlier sources. The very compilation of the List seems to lead up to the Isin Dynasty itself, which would give it much legitimacy in the minds of the people because the dynasty would then be linked to earlier (albeit sometimes legendary) kings.[15]

See also

References

- ETCSL. Sumerian King List . Accessed 19 Dec 2010.

- Raymond P. Dougherty, An Archæological Survey in Southern Babylonia I, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 23, pp. 15-28, 1926

- Excavations in Iraq 1972-73, Iraq, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 192, 1973

- Excavations in Iraq 1973-74, Iraq, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 57-58, 1975

- Excavations in Iraq 1975, Iraq, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 69-70, 1976

- Excavations in Iraq 1977-78, Iraq, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 150, 1979

- Excavations in Iraq 1983-84, Iraq, vol. 47, pp. 221, 1985

- Excavations in Iraq 1985-86, Iraq, vol. 49, pp. 239-240, 1987

- Excavations in Iraq 1987-88, Iraq, vol. 51, pp. 256, 1989

- Excavations in Iraq 1989–1990, Iraq, vol. 53, pp. 175-176, 1991

- Vaughn E. Crawford, An Ishbi-Irra Date Formula, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 13-19, 1948

- William W. Hallo, The Last Years of the Kings of ISIN, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 54-72, 1959

- de Boer, Rients. "Studies on the Old Babylonian Kings of Isin and Their Dynasties with an Updated List of Isin Year Names" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, 2021, pp. 5-27.

- A. Livingstone, The Isin "Dog House" Revisited, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 54-60, 1988

- M. B. Rowton, The Date of the Sumerian King List, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 156-162, 1960

Further reading

- Vaughn Emerson Crawford, Sumerian economic texts from the first dynasty of Isin, Yale University Press, 1954

- Frayne, D. R, (1998): New light on the reign of Išme-Dagan, ZA 88, 6-44

- Goetze, A. (1965): Date formula of Iddin-Dagān of Isin, JCS 19, 56

- Barthel Hrouda, Isan Bahriyat I. D. Ergebnisse d. Ausgrabungen 1973–1974 (Veroffentlichungen der Kommission zur Erschliessung von Keilschrifttexten), In Kommission bei der C.H. Beck, 1977, ISBN 3-7696-0074-6

- Barthel Hrouda, Isin, Isan Bahriyat II: Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen 1975–1978 (Veroffentlichungen der Kommission zur Erschliessung von Keilschrifttexten), In Kommission bei der C.H. Beck, 1981, ISBN 3-7696-0082-7

- Barthel Hrouda, Isin, Isan Bahriyat III: Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen 1983–1984 (Veroffentlichungen der Kommission zur Erschliessung von Keilschrifttexten), In Kommission bei C.H. Beck, 1987, ISBN 3-7696-0089-4

- Barthel Hrouda, Isin, Isan Bahriyat IV: Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen, 1986–1989 (Veroffentlichungen der Kommission zur Erschliessung von Keilschrifttexten), In Kommission bei C.H. Beck, 1992, ISBN 3-7696-0100-9

- Kaniuth, Kai. "18. Isin in the Kassite Period". Volume 2 Karduniaš. Babylonia under the Kassites 2, edited by Alexa Bartelmus and Katja Sternitzke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2017, pp. 492-507

- M. van de Mieroop, Crafts in the Early Isin Period: A Study of the Isin Craft Archive from the Reigns of Isbi-Erra and Su-Illisu, Peeters Publishers, 1987, ISBN 90-6831-092-5

- Wilcke, C., Edzard, D. O., Walker, C., Odzuck, S., & Sommerfeld, W. (2018). Keilschrifttexte aus Isin-Išān Baḥrīyāt: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft unter der Schirmherrschaft der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Bayerische Akademie d. Wissenschaften.

External links

- Archaeological Site Photographs of Isin at Oriental Institute

- Iraqi Looters Tearing Up Archaeological Sites Edmund L. Andrews. The New York Times, May 23, 2003.