Ubaid period

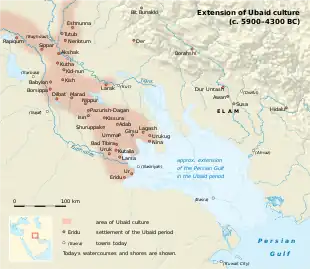

The Ubaid period (c. 5500–3700 BC)[1] is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.[2][3]

A clickable map of Iraq detailing important sites that were occupied during the Ubaid period. | |

| Geographical range | Near East |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 5500 – c. 3700 BC |

| Type site | Tell al-'Ubaid |

| Major sites | |

| Preceded by | |

| Followed by | |

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium.[4] In the south it has a very long duration between about 5500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.[5]

In Northern Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC.[5] It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

History of research

The term "Ubaid period" was coined at a conference in Baghdad in 1930, where at the same time the Jemdet Nasr and Uruk periods were defined.[6]

Dating, extent and periodization

The Ubaid period is divided into four principal phases:

- Ubaid 0, sometimes called Oueili, (5500–5400 BC), an early Ubaid phase first excavated at Tell el-'Oueili.

- Ubaid 1, sometimes called Eridu[7] corresponding to the city Eridu, (5400–4700 BC), a phase limited to the extreme south of Iraq, on what was then the shores of the Persian Gulf. This phase, showing clear connection to the Samarra culture to the north, saw the establishment of the first permanent settlement south of the 5 inch rainfall isohyet. These people pioneered the growing of grains in the extreme conditions of aridity, thanks to the high water tables of Southern Iraq.[8]

- Ubaid 2[7] (4800–4500 BC). At that time, Hadji Muhammed style ceramics was produced. This period also saw the development of extensive canal networks near major settlements. Irrigation agriculture, which seems to have developed first at Choga Mami (4700–4600 BC) and rapidly spread elsewhere, form the first required collective effort and centralised coordination of labour in Mesopotamia.[9]

- Ubaid 3: Tell al‐Ubaid style ceramics. Traditionally, this ceramic period was dated c. 5300–4700 BC. The appearance of these ceramics received different dates depending on the particular sites, which have a wide geographical distribution. In recent studies, there's a tendency to narrow this period somewhat.

- Ubaid 4: Late Ubaid style ceramics, c. 4700–4200 BC.[10][11][12]

Description

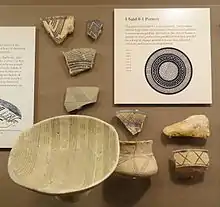

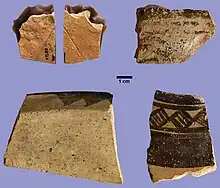

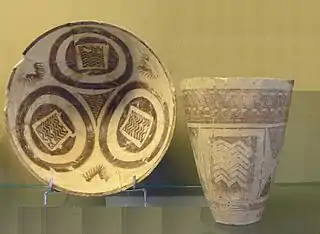

Ubaid culture is characterized by large unwalled village settlements, multi-roomed rectangular mud-brick houses and the appearance of the first temples of public architecture in Mesopotamia, with a growth of a two tier settlement hierarchy of centralized large sites of more than 10 hectares surrounded by smaller village sites of less than 1 hectare.[13] Domestic equipment included a distinctive fine quality buff or greenish colored pottery decorated with geometric designs in brown or black paint. Tools such as sickles were often made of hard fired clay in the south, while in the north stone and sometimes metal were used. Villages thus contained specialised craftspeople, potters, weavers and metalworkers, although the bulk of the population were agricultural labourers, farmers and seasonal pastoralists.

During the Ubaid Period (5000–4000 BC), the movement towards urbanization began. "Agriculture and animal husbandry [domestication] were widely practiced in sedentary communities".[14] There were also tribes that practiced domesticating animals as far north as Turkey, and as far south as the Zagros Mountains.[15] The Ubaid period in the south was associated with intensive irrigated hydraulic agriculture, and the use of the plough, both introduced from the north, possibly through the earlier Choga Mami, Hadji Muhammed and Samarra cultures.

Society and social organization

The Ubaid period as a whole, based upon the analysis of grave goods, was one of increasingly polarized social stratification and decreasing egalitarianism. Bogucki describes this as a phase of "Trans-egalitarian" competitive households, in which some fall behind as a result of downward social mobility. Morton Fried and Elman Service have hypothesised that Ubaid culture saw the rise of an elite class of hereditary chieftains, perhaps heads of kin groups linked in some way to the administration of the temple shrines and their granaries, responsible for mediating intra-group conflict and maintaining social order. It would seem that various collective methods, perhaps instances of what Thorkild Jacobsen called primitive democracy, in which disputes were previously resolved through a council of one's peers, were no longer sufficient for the needs of the local community.

Ubaid culture originated in the south, but still has clear connections to earlier cultures in the region of middle Iraq. The appearance of the Ubaid folk has sometimes been linked to the so-called Sumerian problem, related to the origins of Sumerian civilisation. Whatever the ethnic origins of this group, this culture saw for the first time a clear tripartite social division between intensive subsistence peasant farmers, with crops and animals coming from the north, tent-dwelling nomadic pastoralists dependent upon their herds, and hunter-fisher folk of the Arabian littoral, living in reed huts.

Stein and Özbal describe the Near East oecumene that resulted from Ubaid expansion, contrasting it to the colonial expansionism of the later Uruk period. "A contextual analysis comparing different regions shows that the Ubaid expansion took place largely through the peaceful spread of an ideology, leading to the formation of numerous new indigenous identities that appropriated and transformed superficial elements of Ubaid material culture into locally distinct expressions."[16]

The earliest evidence for sailing has been found in Kuwait indicating that sailing was known by the Ubaid 3 period.[17]

There is some evidence of warfare during the Ubaid period although it is extremely rare. The "Burnt Village" at Tell Sabi Abyad could be suggestive of destruction during war but it could also have been due to other causes, such as wildfire or accident. Ritual burning is also possible since the bodies inside were already dead by the time they were burned. A mass grave at Tepe Gawra contained 24 bodies apparently buried without any funeral rituals, possibly indicating it was a mass grave from violence. Copper weapons were also present in the form of arrow heads and sling bullets, although these could have been used for other purpose; two clay pots recovered from the era have decorations showing arrows used for the purpose of hunting. A copper axe head was made in the late Ubaid period, which could have been a tool or a weapon.[18]

Trade, economy, geographical links, and historical context

Influence to the north

Around 5000 BC, the Ubaid culture spread into northern Mesopotamia and was adopted by the Halaf culture.[19][20] This is known as the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period of northern Mesopotamia.

During the late Ubaid period around 4500–4000 BC, there was some increase in social polarization, with central houses in the settlements becoming bigger. But there were no real cities until the later Uruk period.

Ubaid influence in the Persian Gulf area

.png.webp)

During the Ubaid 2 and 3 periods (5500–5000 BC), southern Mesopotamian Ubaid influence is felt further to the south along the coast of the Persian Gulf. Kuwait was the central site of interaction between the peoples of Mesopotamia and Neolithic Eastern Arabia,[21][22][23][24][25] including Bahra 1 and site H3 in Subiya.[21][26][27][28] Ubaid artifacts spread also all along the Arabian littoral, showing the growth of a trading system that stretched from the Mediterranean coast through to Oman.[29][30]

Spreading from Eridu, the Ubaid culture extended from the Middle of the Tigris and Euphrates to the shores of the Persian Gulf, and then spread down past Bahrain to the copper deposits at Oman.

Obsidian trade

Starting around 5500 BC, Ubaid pottery of periods 2 and 3 has been documented at site H3 in Kuwait and in Dosariyah in eastern Saudi Arabia.

In Dosariyah, nine samples of Ubaid-associated obsidian were analyzed. They came from eastern and northeastern Anatolia, such as from Pasinler, Erzurum, as well as from Armenia. The obsidian was in the form of finished blade fragments.[31]

Decline of influence

The archaeological record shows that Arabian Bifacial/Ubaid period came to an abrupt end in eastern Arabia and the Oman peninsula at 3800 BC, just after the phase of lake lowering and onset of dune reactivation.[32] At this time, increased aridity led to an end in semi-desert nomadism, and there is no evidence of human presence in the area for approximately 1,000 years, the so-called "Dark Millennium".[33] The increased aridity might have been due to the 5.9 kiloyear event at the end of the Older Peron.[32]

Numerous examples of Ubaid pottery have been found along the Persian Gulf, as far as Dilmun, where Indus Valley civilization pottery has also been found.[34]

Arts and crafts

Ubaid 0 artifacts (c. 5500 – c. 5400 BC)

Stamp seal and modern impression: horned animal and bird. 6th–5th millennium BC. Northern Syria or southeastern Anatolia. Ubaid period. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stamp seal and modern impression: horned animal and bird. 6th–5th millennium BC. Northern Syria or southeastern Anatolia. Ubaid period. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ubaid 1 artifacts (c. 5400 – c. 4700 BC)

.jpg.webp) Bowl; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 5.08 cm; from the Ubaid period

Bowl; mid 6th–5th millennium BC; ceramic; 5.08 cm; from the Ubaid period

Early Ubaid pottery, 5100–4500 BC, Tepe Gawra. Louvre Museum DAO 3

Early Ubaid pottery, 5100–4500 BC, Tepe Gawra. Louvre Museum DAO 3

Ubaid 2 artifacts (c. 4800 – c. 4500 BC)

Ubaid 3 artifacts (c. 5300 – c. 4700 BC)

Ubaid 4 artifacts (c. 4700 – c. 4200 BC)

Ubaid IV pottery jars 4700–4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum.[37]

Ubaid IV pottery jars 4700–4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum.[37] Ubaid IV pottery 4700–4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum AO 15338.[38]

Ubaid IV pottery 4700–4200 BC Tello, ancient Girsu, Louvre Museum AO 15338.[38]

Two female figurines with bitumen headdresses, ceramic. Ur, Ubaid 4 period, 4500–4000 BC

Two female figurines with bitumen headdresses, ceramic. Ur, Ubaid 4 period, 4500–4000 BC.jpg.webp) Lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child, from Ur, Iraq, c. 4000 BCE.

Lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child, from Ur, Iraq, c. 4000 BCE. Pottery jar from Late Ubaid Period

Pottery jar from Late Ubaid Period_pendant_seal_and_modern_impression._Quadrupeds%252C_ca._4500%E2%80%933500_B.C._Late_Ubaid_-_Middle_Gawra._Northern_Mesopotamia.jpg.webp) Drop-shaped (tanged) pendent seal and modern impression. Quadrupeds, not entirely reduced to geometric shapes, ca. 4500–3500 BC. Late Ubaid - Middle Gawra periods. Northern Mesopotamia

Drop-shaped (tanged) pendent seal and modern impression. Quadrupeds, not entirely reduced to geometric shapes, ca. 4500–3500 BC. Late Ubaid - Middle Gawra periods. Northern Mesopotamia

See also

| History of Iraq |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

| The Neolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Mesolithic |

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

References

- Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number 63) The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0 p. 2; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 5500 to 3800 B.C."

- Henry R.H. Hall, C.L. Woolley, et al., "Al 'Ubaid", 1927

- Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard. 1927. Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) Upon This Foundation - The ’Ubaid Reconsidered. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451–456.

- Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.

- Matthews, Roger (2002), Secrets of the dark mound: Jemdet Nasr 1926-1928, Iraq Archaeological Reports, vol. 6, Warminster: BSAI, ISBN 0-85668-735-9

- Kurt, Amélie Ancient near East V1 (Routledge History of the Ancient World) Routledge (31 Dec 1996) ISBN 978-0-415-01353-6 p. 22

- Roux, Georges "Ancient Iraq" (Penguin, Harmondsworth)

- Wittfogel, Karl (1981) "Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power (Vintage Books)

- Carter, R. (2010). Pottery from H3. In R. Carter & H. Crawford (Eds.), Maritime interactions in the Arabian Neolithic: The evidence from H3, As‐Sabiyah, an Ubaid‐related site in Kuwait (pp. 33–65). Leiden: Brill.

- Carter, R., & Philip, G. (2010). Deconstructing the Ubaid. In R.A. Carter & G. Philip (Eds.), Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and integration in the Late Prehistoric societies of the Middle East. (SAOC, 63) (pp. 1–22). Chicago, IL: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p.2

- Ashkanani, Hasan J.; Tykot, Robert H.; Al‐Juboury, Ali Ismail; Stremtan, Ciprian C.; Petřík, Jan; Slavíček, Karel (2019). "A characterisation study of Ubaid period ceramics from As‐Sabbiya, Kuwait, using a non‐destructive portable X‐Ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectrometer and petrographic analyses". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1111/aae.12143. ISSN 0905-7196.

- "Figurine féminine d'Obeid". 2019.

- Pollock, Susan (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57334-3.

- Pollock, Susan (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57334-3.

- Stein, Gil J.; Rana Özbal (2006). "A Tale of Two Oikumenai: Variation in the Expansionary Dynamics of Ubaid and Uruk Mesopotamia". In Elizabeth C. Stone (ed.). Settlement and Society: Ecology, urbanism, trade and technology in Mesopotamia and Beyond (Robert McC. Adams Festschrift). Santa Fe: SAR Press. pp. 329–343. ISBN 1-885923-48-1.

- Carter, Robert (2006). "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC". Antiquity. 80 (307): 52–63. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0009325X.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy warriors at the dawn of history. Routledge. p. 28-29.

- Susan Pollock; Reinhard Bernbeck (2009). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. p. 190. ISBN 9781405137232.

- Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 157. ISBN 9780521796668.

- Carter, Robert (2019). "The Mesopotamian frontier of the Arabian Neolithic: A cultural borderland of the sixth–fifth millennia BC". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1111/aae.12145.

- Carter, Robert (25 October 2010). Maritime Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic: The Evidence from H3, As-Sabiyah, an Ubaid-Related Site in Kuwait. BRILL. ISBN 9789004163591.

- Carter, Robert. "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC" (PDF).

- Carter, Robert. "Maritime Interactions in the Arabian Neolithic: The Evidence from H3, As-Sabiyah, an Ubaid-Related Site in Kuwait".

- "How Kuwaitis lived more than 8,000 years ago". Kuwait Times. 2014-11-25.

- Carter, Robert (2002). "Ubaid-period boat remains from As-Sabiyah: excavations by the British Archaeological Expedition to Kuwait". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 32: 13–30. JSTOR 41223721.

- Carter, Robert; Philip, Graham. "Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and integration in the late prehistoric societies of the Middle East" (PDF).

- "PAM 22". pcma.uw.edu.pl.

- Bibby, Geoffrey (2013), "Looking for Dilmun" (Stacey International)

- Crawford, Harriet E. W. (1998), "Dilmun and its Gulf Neighbours" (Cambridge University Press)

- Lamya Khalidi, Bernard Gratuze, Gil Stein, Augusta Mcmahon, Salam Al-Quntar, et al.. The growth of early social networks: New geochemical results of obsidian from the Ubaid to Chalcolithic Period in Syria, Iraq and the Gulf. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Elsevier, 2016, doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.06.026 ⟨halshs-01390232⟩

- Parker, Adrian G.; et al. (2006). "A record of Holocene climate change from lake geochemical analyses in southeastern Arabia" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 66 (3): 465–476. Bibcode:2006QuRes..66..465P. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.07.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008.

- Uerpmann, M. (2002). "The Dark Millennium—Remarks on the final Stone Age in the Emirates and Oman". In Potts, D.; al-Naboodah, H.; Hellyer, P. (eds.). Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates. Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Archaeology of the U.A.E. London: Trident Press. pp. 74–81. ISBN 1-900724-88-X.

- Stiebing, William H. Jr. (2016). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9781315511160.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Figurine féminine d'Obeid". 2019.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 304. ISBN 9781614510352.

- Charvát, Petr (2003). Mesopotamia Before History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781134530779.

Further reading

- Martin, Harriet P. (1982). "The Early Dynastic Cemetery at al-'Ubaid, a Re-Evaluation". Iraq. 44 (2): 145–185. doi:10.2307/4200161. JSTOR 4200161.

- Moore, A. M. T. (2002). "Pottery Kiln Sites at al 'Ubaid and Eridu". Iraq. 64: 69–77. doi:10.2307/4200519. JSTOR 4200519.

- Bogucki, Peter (1990). The Origins of Human Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 1-57718-112-3.

- Charvát, Petr (2002). Mesopotamia Before History. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25104-4.

- Mellaart, James (1975). The Neolithic of the Near East. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-14483-2.

- Nissen, Hans J. (1990). The Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000–2000 B.C.. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-58658-8.

.jpg.webp)