Maryul

Maryul (Ladakhi: མརཡུལ།) also called mar-yul of mngah-ris,[1][2] was the western most Tibetan kingdom based in modern-day Ladakh and some parts of Tibet. The kingdom had its capital at Shey.[3][4][5]

Maryul མརཡུལ། | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 930–1842 | |||||||||

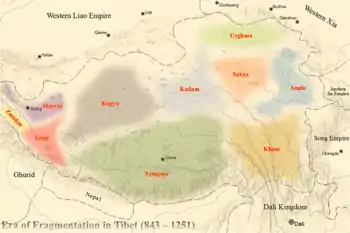

Location of Maryul and neighbouring polities in the early 1000s. | |||||||||

| Capital | Shey | ||||||||

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• c. 930–c. 960 | Lhachen Palgyigon (first) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | c. 930 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1842 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China India Pakistan | ||||||||

The kingdom was founded by Lhachen Palgyigon, during the rule of his father Kyide Nyimagon, in c. 930.[6] It stretched from the Zoji La at the border of Kashmir to Demchok in the southeast, and included Rudok and other areas presently in Tibet.[7][8] The kingdom came under the control of the Namgyal dynasty in 1460, eventually acquiring the name "Ladakh", and lasted until 1842. In that year, the Dogra general Zorawar Singh, having conquered it, made it part of the would-be princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Etymology

Mar-yul has been interpreted in Tibetan sources as lowland (of Ngari),.[9] Scholars suspect that it was a proper name that was in use earlier, even before Ladakh was Tibetanised. For instance, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang referred to it as Mo-lo-so, which would lead to a reconstructed name such as *Malasa, *Marāsa, or *Mrāsa.[10][11] The Annals of Tun‐Huang state that the Tibetan government carried out a census of Zan-zun and Mar(d) in 719 CE.[12] The Persian text Hudud al-Alam (c. 982) refers to a "wealthy country of Tibet", with a tribe named Mayul.[13] These facts suggest that Mar-yul ("land of Mar") might have been a proper name of the country.

The name was in use at least until the 16th century. Mirza Haidar Dughlat referred to it as Maryul and named a region called "Ladaks" that was apparently distinct from Maryul.[14] It was also used by the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Francisco de Azevedo when he visited Ladakh in 1631, but his usage of the name has been described as Luciano Petech as referring to neither the Kingdom of Ladakh nor Rudok.[15]

The newer name La-dwags ལ་དྭགས (historically transliterated as La-dvags) means "land of high passes". Ladak is its pronunciation in several Tibetan districts, and Ladakh is a transliteration of the Persian spelling.[16]

Background

Upon the assassination of emperor Langdarma in c. 842, Tibetan empire became fragmented over a succession dispute that would linger for centuries. By late ninth century, one of his grandsons Depal Khortsen was controlling most of Central Tibet. Upon his assassination, one of his sons Kyide Nyimagon (Wylie: sKyid-lde Nyi-ma-mgon), made it to West Tibet — the causes are disputed.

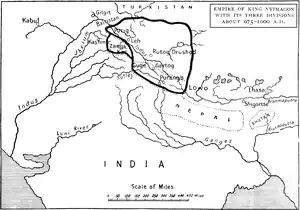

Nyimagon entered into a marital alliance with a high-nobility of Purang and established his kingdom, stretching from the Mayum La in the east to the Zoji La in the west. Upon his death c. 930, his vast kingdom was divided among his three sons: the eldest son, Lhachen Palgyigon, receiving Maryul, the second son, Trashigon, receiving Guge and Purang, and the third son, Detsukgon, receiving Zanskar (mountainous area between Ladakh and Kashmir).[lower-alpha 1][3]

Thus, the Kingdom of Maryul was founded by Lhachen Palgyigon (dPal-gyi-mgon) when he was still a prince.[6]

Description

The kingdom of Maryul is described in the Ladakh Chronicles (Francke's translation) to consist of:[19][20][lower-alpha 2]

- Mar-yul of mNah-ris (Leh district), the inhabitants using the black bows; Ru-thogs (Rudok) of the east and the gold mine of hGog (possibly Thok Jalung); nearer this way lDe-mchog-dkar-po (Demchok Karpo);[lower-alpha 3]

- at the frontier:

- Ra-ba-dmar-po (possibly near Rabma, which lies halfway between Spanggur and Rudok);[25][lower-alpha 4]

- Wam-le (Hanle), to the top of the pass of the Yi-mig rock (Imis Pass);

- to the west to the foot of the Kashmir pass (Zoji La), from the cavernous stone upward hither,

- to the north to the gold mine of hGog;

- all the places belonging to rGya (Gya, on the way from Leh to Rupshu).

The description makes clear that Purig (the Suru River basin near present-day Kargil) was included in Maryul, but Zanskar to the west was not. The latter went to the third son Detsukgon along with Lahul and Spiti. The Rupshu highland was regarded as the frontier between Maryul and Zanskar.[27] Baltistan to the north was also not included in Maryul.[11]

The southern border of Maryul towards Guge is much harder to discern. A. H. Francke believed that the second heir Tashigon received "a long and narrow strip of country along the northern slope of the Himalayas, of which Purang and Guge are the best-known provinces". Maryul encompassed all the areas to the north of this narrow strip.[28][lower-alpha 5] This view is not favoured by other scholars. Luciano Petech opined that Palgyigon received the territories that he himself conquered, whereas the paternal territory was divided among the other two sons.[18] He also favoured Zahidurddin Ahmad's revised translation of the text from Ladakh Chronicles, which states that all the places mentioned in the description lie on the frontier of Maryul, including Demchok Karpo and Raba Marpo.[21]

First dynasty (930–1460)

Scholar Luciano Petech says that even though Palgyigon's father theoretically bequeathed Maryul to him, the actual conquest of the territories was carried out by Palgyigon himself, whom Petech identifies as "the founder and organiser of the Ladakhi kingdom".[18]

It appears that the second son Trashigon, who inherited Guge, died without issue. His kingdom was acquired by Detsukgon of Zanskar. The latter's son, Yeshe-Ö became a prominent ruler that reestablished Buddhism in West Tibet and Tibet in general. Maryul, belonging to the senior branch, is believed to have extended some form of suzerainty over the other branches.[28][30]

By 1100 AD, the kingdom of Guge was sufficiently weakened that the king Lhachen Utpala of Maryul brought it under his control. From this time onward, Guge was generally subsidiary to Maryul.[31][lower-alpha 6]

After a period of Kashmiri invasions in the mid-15th century, the last king of the west Tibetan dynasty, Blo-gros-mc-og-Idan, reigned from c. 1435 to c. 1460.[35] During his reign, Blo-gros-mc-og-Idan sent presents to the 1st Dalai Lama, patronized the Gelug scholar gSan-p'u-ba Lha dban-blo-gros, and raided the Kingdom of Guge.[36] The final years of his reign were disastrous, and he was eventually deposed in 1460, ending his dynasty.[37]

Second dynasty (1460–1842)

In 1460, the Namgyal dynasty was established.[38] According to the Ladakh Chronicles, the warlike Lhachen Bhagan formed an alliance with the people of Leh and dethroned the Maryul king Blo-gros-mc-og-ldan and his brothers drun-pa A-li and Slab-bstan-dar-rgyas.[39]

Sengge Namgyal (r. 1616–1642), the "Lion" King, made efforts to restore Ladakh to its old glory by an ambitious and energetic building program including the Leh Palace and the rebuilding of several gompas, the most famous of which are Hemis and Hanle.[40]

Treaty of Tingmosgang

Guge was annexed by Ladakh in the second quarter of the 17th century. This invited retaliation from Lhasa, whose forces drove out the Ladakhis and laid siege to Ladakh itself.[41] Ladakh was forced to seek help from the Mughal Empire in Kashmir, leading to the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War. At the end of the conflict, in 1684, the Treaty of Tingmosgang was agreed, affirming that:

The boundaries fixed, in the beginning, when king Skyed-lda-ngeema-gon [Nyimagon] gave a kingdom to each of his three sons shall still be maintained.[42]

Despite the apparent invocation of the "boundaries fixed in the beginning", the extensive dominions granted in the original inheritance were not retained by Maryul. The treaty itself makes clear that Rudok was no more a part of Maryul and various restrictions were placed on trade with Rudok. Scholar Gerhard Emmer states that Ladakh was reduced to approximately its current extent. It was henceforth treated as being outside Ngari Khorsum, as a buffer state against Mughal India. The territories of Guge, Purang and Rudok were annexed to Tibet and the frontier with Tibet was fixed at the Lha-ri stream near Demchok.[43][44] The reason for this exclusion was apparently Ladakh's syncretism and its willingness to ally with Mughal India. Ladakh was instructed in the treaty:[45]

to keep watch at the frontier of Buddhist and non-Buddhist peoples, and out of regard for the doctrine of Buddha ... not allow any army from India to proceed to an attack [upon Tibet].[46]

Dogra–Tibetan War

The Namgyal dynasty ended in 1842 after an invasion of Ladakh from the Dogra dynasty of Jammu and Kashmir.[47]

A historical claim was again made in the 19th century, after the Dogra general Zorawar Singh conquered Ladakh. Singh claimed all of western Tibet up to the Mayum Pass as Ladakhi territory and occupied it.[48] Once again, Lhasa dispatched troops that defeated Zorawar Singh and laid siege to Leh. After the Dogras received reinforcements, a stalemate was obtained and the Treaty of Chushul reconfirmed the "old, established frontiers".[49]

See also

Notes

- The Tibetan names of the three sons in Wylie transliteration are: Lhachen Palgyigon (lHa-chen dPal-gyi-mgon), Trashigon (bKra-shis-mgon) and Detsukgon (lDe-gtsug-mgon). The three sons together were referred to as three sTodmgon.[17][18]

- In 1968, Zahiruddin Ahmad gave a revised translation, by which he suggested that all the places mentioned in the text were on the frontier of Maryul.[21] His revisions have not been generally accepted by modern scholars.[22]

- "Demchok Karpo" is identified by most scholars as the village of Demchok at the southern border between Ladakh and Tibet. The literal meanings are as follows: Karpo means white in Tibetan. It also has figurative meanings such as pure, wholesome, positive, good etc.[23] Demchok is the Tibetan name of the Vajrayana Buddhist deity Chakrasamvara, who is believed to reside at Mount Kailas along with his consort Vajravarahi. The association with the Mount Kailas may be later than the 10th century. The tradition states that Demchok defeated Mahesvara and took his place on top of Sumeru.[24]

- Rabma was marked by Henry Strachey at approximately 33.3740°N 79.2935°E on a stream, which came down from the Kailash Range and joined the Tangre Chu river before draining into Spanggur Tso. A map compiled in 2009 by an amateur cartographer notes the source of this stream (unnamed) to be below a pass called 'Rabmar La' (33.1936°N 79.3009°E), which laid on the erstwhile boundary between Rutog County and Sengge Zangbo County.[26] (The boundary has now been changed under the Chinese administration.)

- Francke's map, reproduced at the top of this page, shows this kind of a border, running slightly to the north of Gartok.[29]

- Further conquests were made by Tashi Namgyal (r. c. 1555 – c. 1575),[32] Tsewang Namgyal I (r. c. 1575 – c. 1595),[33] and Sengge Namgyal (r. 1624–1642).[34]

References

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 19: "Mar-yul (literally "lower land") is the common Tibetan name for the Leh district in Ladakh. Mngah-ris (Mnga-ris), although now restricted to West Tibet, then referred to the entire territory between the Zoji and Mayum passes."

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977).

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 18–19.

- Dorjay, Embedded in Stone (2014), p. 53: "Shey, about 15 km southeast of Leh, was an ancient capital of Ladakh. In the tenth century CE the first king of Ladakh, lHa chen dPal gyi mgon, apparently constructed the hilltop fortress whose ruins can be seen above the present Shey Palace. Shey possesses a number of early Buddhist rock sculptures, many of which are about a metre in height."

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 88: From the diary of Mirza Haidar Dughlat: "The Chui [Jo plural, i.e. rulers] of Maryul, named Tashikun and Lata Jughdan, ...... gave us the castle of Sheya [Shey] which is the capital of Maryul [to live in during the winter]"

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 17: "it seems that his father bequeathed him a theoretical right of sovereignty, but the actual conquest was effected by dPal-gyi-mgon himself."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 19: "The Ladakhi chronicles state that the eldest son, Pal-gyi-gön (Dpal-gyi-mgon), received Ladakh and the Rudok area;..."

- Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet (1992), p. 94.

- Strachey, Capt. H. (1853), "Physical Geography of Western Tibet", The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Volume 23, Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain), p. 13: "Maryul signifies in Tibetan the Low Country, a term appropriate to the character of its inhabited valleys as contrasted with Nari-Khorsum"

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), pp. 7–8.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 86.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 8.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), pp. 86–87.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 88.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), pp. 54.

- "Ladakh, the Persian transliteration of the Tibetan La-dvags, is warranted by the pronunciation of the word in several Tibetan districts." Francke(1926) Vol. I, p. 93, notes.

- Powers & Templeman, Historical Dictionary of Tibet (2012), p. 27.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 17.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p.19.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 83.

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (September–December 1968), "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", East and West, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO), 18 (3/4): 340–341, JSTOR 29755343

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 84.

- dkar po, Tibetan & Himalayan Library, retrieved 21 October 2019.

- McKay, Alex (2015). Kailas Histories: Renunciate Traditions and the Construction of Himalayan Sacred Geography. BRILL. pp. 5, 304–305, 316. ISBN 978-90-04-30618-9.

- Ahmad, The Ancient Frontier of Ladakh (1960), p. 315.

- Map 3379, Maps of Tibet, Claude Andre of The Tibet Map Institute, July 2009.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 19.

- Francke, A History of Western Tibet (1907), p. 63.

- Francke, A History of Western Tibet (1907), pp. 60–61.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963): p. 20: "Francke asserts that the eldest son (i.e., the ruler of Ladakh) was suzerain over his brothers, and that Ladakh thus exercised some form of authority over West Tibet, Zanskar, Spiti, and Lahul." p. 21: "On several occasions expansionist rulers of Ladakh laid claim to West Tibet on the basis of past association, but there are no recorded instances in which the reverse occurred."

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), pp. 130, 224–225.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), pp. 89–90.

- Francke, A History of Western Tibet (1907), p. 86.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 90.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 23.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 23–24.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 24.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 171.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), p. 25.

- Rizvi, Ladakh 1996, p. 69

- McKay, History of Tibet, Vol. 2 (2003), p. 3.

- McKay, History of Tibet, Vol. 2 (2003), p. 785.

- Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007), pp. 99–100.

- Shakspo, Nawang Tsering (1999), "The Foremost Teachers of the Kings of Ladakh", in Martijn van Beek; Kristoffer Brix Bertelsen; Poul Pedersen (eds.), Recent Research on Ladakh 8, Aarhus University Press, p. 288, ISBN 978-87-7288-791-3

- Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007), pp. 92, 100.

- Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet (1992), p. 116.

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), pp. 1, 138–170.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 50: "Zorawar Singh then announced his intention to conquer in the name of the Jammu Raja all of Tibet west of the Mayum Pass, on the ground that this territory had rightfully belonged, since ancient times, to the ruler of Ladakh."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 55–56.

Bibliography

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (July 1960), "The Ancient Frontier of Ladakh", The World Today, 16 (7): 313–318, JSTOR 40393242

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mugha1 War of 1679-84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, pp. 81–108, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Francke, August Hermann (1907), A History of Western Tibet, S. W. Partridge & Co – via archive.org

- Francke, August Hermann (1992) [first published 1926]. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. p. 94. ISBN 81-206-0769-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Handa, O. C. (2001), Buddhist Western Himalaya: A politico-religious history, Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-124-5

- Lo Bue, Erberto; Bray, John, eds. (2014), "Introduction", Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-27180-7

- Dorjay, Phuntsog (2014), "Embedded in Stone—Early Buddhist Rock Art of Ladakh", Ibid, pp. 35–67, ISBN 9789004271807

- Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014), "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul", Ibid, pp. 68–99, ISBN 9789004271807

- McKay, Alex (2003), History of Tibet, Volume 2: The Medieval Period: c.850-1895, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30843-7 – via archive.org

- Petech, Luciano (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D., Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente – via archive.org

- Powers, John; Templeman, David (2012), Historical Dictionary of Tibet, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-7984-3

- Rizvi, Janet (1996), Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia (Second ed.), Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564546-4

.jpg.webp)