Demchok (historical village)

Demchok (Tibetan: ཌེམ་ཆོག, Wylie: bde mchog, THL: dem chok, ZYPY: dêmqog),[1][lower-alpha 1] was described by a British boundary commission in 1847 as a village lying on the border between the Kingdom of Ladakh and the Tibet. It was a "hamlet of half a dozen huts and tents", divided into two parts by a rivulet which formed the boundary between the two states.[5][6] The rivulet, a tributary of the Indus River variously called the Demchok River, Charding Nullah, or the Lhari stream, was set as the boundary between Ladakh and Tibet in the 1684 Treaty of Tingmosgang. By 1904–05, the Tibetan side of the hamlet was said to have had 8 to 9 huts of zamindars (landholders), while the Ladakhi side had two.[7] The area of the former Demchok now straddles the Line of Actual Control, the effective border of the People's Republic of China's Tibet Autonomous Region and the Republic of India's Ladakh Union Territory.

Demchok

བདེ་མཆོག | |

|---|---|

Village | |

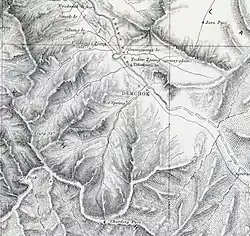

Demchok depicted in a Survey of India map of 1874 | |

Demchok  Demchok | |

| Coordinates: 32°42′0″N 79°27′30″E | |

| Elevation | 4,220 m (13,850 ft) |

| Languages | |

Name

The village of Demchok was apparently named after Demchok Karpo, the rocky white peak behind the present Ladakhi village of Demchok.[8][9] However, prior to 1947, the main Demchok village was on the Tibetan side of the border.[10] The Ladakhi side of the settlement was still referred to as "Demchok".[11]

Chinese officials use the name "Demchok" only for the Tibetan side of the settlement and refer to the Ladakhi side as "Parigas" (also spelt "Barrigas").[12]

History

Demchok is a historic area of Ladakh, having been part of the kingdom from its inception in the 10th century. The description of the kingdom in the Ladakh Chronicles mentions Demchok Karpo, also called Demchok Lhari Karpo or Lhari Karpo,[13] as being part of the original kingdom.[14][15] This is a possible reference to the rocky white peak behind the Ladakhi side of the Demchok village.[16][17][8] [lower-alpha 2] The Lhari peak is held sacred by Buddhists. Demchok (Sanskrit: Cakrasaṃvara) is the name of a Buddhist Tantric deity, who is believed to reside on the Mount Kailas, and whose imagery parallels that of Shiva in Hinduism.[20][21] The Lhari peak is also referred to as "Chota Kailas" (mini Kailas) and attracts pilgrimage from Hindus as well as Buddhists.[22][23] Tibetologist Nirmal C. Sinha states that Demchok is part of the Hemis complex.[24] Ruined houses belonging to the Hemis monastery were noticed by Sven Hedin in 1907,[16] and the monastery continues to own land in Demchok.[25]

17th century

The Chronicles of Ladakh mention that, at the conclusion of the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War in 1684, the Prime Minister Desi Sangye Gyatso of Ganden Phodrang Tibet[26] and the King of Ladakh Delek Namgyal[27][28] agreed on the Treaty of Tingmosgang. The chronicles describe the treaty as fixing the boundary at "the Lhari stream at Demchok".[6][29][30]

According to Alexander Cunningham, "A large stone was then set up as a permanent boundary between the two countries, the line of demarcation drawn from the village of Dechhog [Demchok] to the hill of Karbonas."[31][32]

British colonial era

British boundary commissioner Henry Strachey visited Demchok in 1847 on the borders of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. He described the village as:

[Demchok] is a hamlet of half a dozen huts and tents, not permanently inhabited, divided by a rivulet (entering the left bank of the Indus) which constitutes the boundary of this quarter between Gnari ... [in Tibet] ... and Ladakh.[33]

The boundary commission determined that the border between the Kashmir and Tibet was at Demchok.[34]

The Survey of Kashmir, Ladak, and Baltistan or Little Tibet of 1847 to 1868 under the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India then made several adjustments to the boundary, described by Alastair Lamb as moving "sixteen miles downstream on the Indus from Demchok".[35] However, Indian commentators state that the revenue records from the period of the survey show that the Demchok area was administered by Ladakh.[36][37]

In 1904–05, a tour report by the Wazir Wazarat (Governor) of Ladakh described the Tibetan side of the hamlet to have 8 to 9 huts of zamindars (landholders) and described the Ladakhi side as having two.[7] When Sven Hedin visited the area in the November 1907, he described Demchok as four or five huts lying on the southeastern bank of the Lhari stream in Tibet, with the Ladakhi side of the Lhari stream only containing the pyramidal Lhari peak and the ruins of two or three houses.[38][16]

Modern era

Chinese-administered village

The Chinese-administered village of Dêmqog lies on the southeast bank of the Charding Nullah and LAC. Before 1984, only 3 households were living in Dêmqog.[39] Since 1984, the local governments have encouraged people to move to Dêmqog from surrounding areas.[39] Dêmqog was officially established as an administrative village in 1990 and had a population of 171 people from 51 households in 2019.[39]

Indian-administered village

The Indian-administered village of Demchok lies on the north-west bank of the Charding Nullah and LAC. According to the 2011 Census of India, the village had a population of 78 people from 31 households.[40] In 2019, the village had a population of 69 people.[41]

See also

Notes

- For the traditional spelling see Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part 2 (1926), pp. 115–116. Variant spellings include Demchog,[2] Demjok,[3] and Dechhog.[4]

- Scholars translate the Tibetan term lha-ri as "soul mountain". Many peaks in Tibet are named lhari including a "Demchok lhari" in the northern suburbs of Lhasa.[18][19] "Karpo", meaning "white", serves to distinguish the Ladakh's mountain peak from the others.

References

- Tibet Autonomous Region (China): Ngari Prefecture, KNAB Place Name Databse, retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Bray, John (Winter 1990), "The Lapchak Mission From Ladakh to Lhasa in British Indian Foreign Policy", The Tibet Journal, 15 (4): 77, JSTOR 43300375

- Henry Osmaston; Nawang Tsering, eds. (1997), Recent Research on Ladakh 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Colloquium on Ladakh, Leh 1993, International Association for Ladakh Studies / Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 299, ISBN 978-81-208-1432-5

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co, p. 328 – via archive.org

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 64–66.

- Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 38.

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 3 (1962), pp. 3–4, 41.

- Arpi, The Case of Demchok (2016), p. 12; Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 160; Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 9: "Changthang: The High Plateau"

- Lhari peak and the Demchok villages, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 3 (1962), pp. 3–4: Quoting the Governor of Ladakh: "I visited Demchok on the boundary with Lhasa. ... A nullah falls into the Indus river from the south-west and it (Demchok) is situated at the junction of the river. Across is the boundary of Lhasa, where there are 8 to 9 huts of the Lhasa zamindars. On this side there are only two zamindars."

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 3 (1962), pp. 3–4.

-

During border discussions in the 1960s, the Chinese government called the Indian village "Parigas" and the Chinese village "Demchok":

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 1 (1962). Chinese officials state: "Parigas was part of the Demchok area. West of Demchok, after crossing the Chopu river, one arrived at Parigas."

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1966), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: January 1965 - February 1966, White Paper No. XII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs – via claudearpi.net: "In fact, it was Indian troops who on September 18, intruded into the vicinity of the Demchok village on the Chinese side of the 'line of actual control' after crossing the Demchok River from Parigas..."

- Report of the Officials, Chinese Report, Part 2 (1962), pp. 10–11.

- Howard & Howard, Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley (2014), p. 83.

- Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part 2 (1926), p. 94.

- Hedin, Southern Tibet (1922), p. 194: "A short distance N. W. of Demchok, the road passes a partly frozen brook [Lhari stream] coming from Demchok-pu, a tributary valley from the left. ... At the left side [Ladakhi side] of the mouth of this little valley, are the ruins of two or three houses, which were said to have belonged to Hemi-gompa. A pyramidal peak at the same.. side of the valley is called La-ri and said to be sacred. The valley, Demchok-pu, itself is regarded as the boundary between Tibet and Ladak."

- Lhari peak and the Demchok villages, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 9 August 2020.

- McKay, Kailas Histories (2015), p. 520.

- Khardo Hermitage (Khardo Ritrö), Mandala web site, University of Virginia, retrieved 21 October 2019.

- The Middle Way: Journal of the Buddhist Society, Volume 81, The Buddhist Society, 2006: "For Hindus, Kailas is home to the great pan-Indian deity Shiva and for Tibetan Buddhists, it is home to the bodhisattva Dem-chog, the Sanskrit deity Chakrasamvara."

- McKay, Kailas Histories (2015), pp. 7, 304, 316.

- First ever Chhota Kailash Yatra begins in Ladakh, State Times, 22 June 2017.

- First batch of Chota Kailash Yatra leaves for Demchok, Daily Excelsior, 23 June 2017.

- Sinha, Nirmal C. (1967), "Demchok (Notes and topics)" (PDF), Bulletin of Tibetology, 4: 23–24: "Demchock is a sacred place within the Hemis complex. The Hemis complex is very ancient (old Sects) and antedates considerably the Yellow Sect and the rise of the Dalai Lamas."

- P.Stobdan, Ladakh concern overrides LAC dispute, The Tribune, 28 May 2020.

- Ahmad, New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679—1684 (1968), p. 342: "Sans-rGyas rGya-mTsho (1653-1705), sDe-pa or Prime Minister of Tibet 1679-1705"

- Ahmad, New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679—1684 (1968), pp. 351–352: "bDe-legs rNam-rGyal, came to the kingship [of Ladakh] [...] Thereupon, the Government of Tibet, being afraid that the King of Ladakh and his troops might, once again, make war (on Tibet), ordered the 'Brug-pa Mi-'pham dBaii-po that he ought to go (to Ladakh) in order to establish peace."

- Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh (1977), pp. 171–172: "bDe-legs-n.g. co-regent (1680-1691)"

- Ahmad, New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679—1684 (1968):

- p. 351: "Now, in 1684, the government of Tibet, headed by the sDe-pa Sans-rGyas rGya-mTsho, annexed Gu-ge to Tibet, and fixed the frontier between Ladakh and Tibet at the lHa-ri stream at bDe-mChog."

- p. 351–353: "We produce now a new translation of the Ladakh Chronicles [...] With this exception, the frontier (of Ladakh) was fixed as from the IHa-ri stream at bDe-mChog."

- p. 356: "The fourth clause fixes the frontier between Ladakh and Tibet at the IHa-ri stream of bDe-mChog, but leaves the King of Ladakh an enclave at Men-ser"

- Francke, Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part 2 (1926), pp. 115–118.

- Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1969), pp. 42–43.

- Cunningham, Ladak (1854), p. 328.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), p. 68.

- Maxwell, India's China War 1970, map opposite p. 40.

- Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 72–73.

- Rao, The India-China Border (1968):

- p.24: "But such an evaluation was seldom done and although most officials traced the boundary correctly along the watershed range running parallel to the river Indus, gross blunders were committed regarding the alignment in the Pangong and Demchok areas. This was apparently due to the unfamiliarity of some of the British officials with the traditional and treaty basis of the boundary and to their mistaking local disputes such as pasture disputes with boundary disputes."

- p.29: "The Kashmir Atlas boundary conflicts also with the first-hand evidence provided by the 1847 Commission. In regard to Demchok, it conflicts with well-established facts of history and with revenue records for the very period that the survey was conducted."

- Bray, The Lapchak Mission (1990), p. 75: "Many of these relationships had their origin in the distant past, and the British at first understood their full significance imperfectly, or not at all."

- Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps (2017), pp. 353–354, 357 'Hedin described the place as follows: "Rolled stones play an important part in the country which we have now reached. The whole of Demchok, the last village on the Tibetan side, is built of them. It consists, however, of only four or five huts with brushwood roofs."'

- "典角村"五代房":见证阿里"边境第一村"变迁" ["Five-generation house" in Dianjiao Village: Witness the changes of Ngari's "No. 1 Border Village"] (in Chinese). China Tibet Network. 11 July 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Leh district census". 2011 Census of India. Directorate of Census Operations. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Sharma, Arteev (17 July 2019). "Lack of infra forcing people to migrate from frontier". Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Bibliography

- India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (1968). "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679—1684". East and West. 18 (3/4): 340–361. JSTOR 29755343.

- Arpi, Claude (December 2016) [abridged version published in Indian Defence Review, 19 May 2017], The Case of Demchok (PDF)

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012), Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged, New Delhi: Rupa Publications – via Academia.edu

- Bray, John (Winter 1990), "The Lapchak Mission From Ladakh to Lhasa in British Indian Foreign Policy", The Tibet Journal, 15 (4): 75–96, JSTOR 43300375

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co – via archive.org

- Francke, August Hermann (1926). Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part 2. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing – via archive.org.

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, pp. 81–108, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Handa, O. C. (2001), Buddhist Western Himalaya: A Politico-Religious History, Indus Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-7387-124-5

- Hedin, Sven (1922), Southern Tibet: Discoveries in Former Times Compared with My Own Researches in 1906–1908: Vol. IV – Kara-korum and Chang-Tang, Stockholm: Lithographic Institute of the General Staff of the Swedish Army

- Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014), "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul", in Erberto Lo Bue; John Bray (eds.), Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, BRILL, pp. 68–99, ISBN 978-90-04-27180-7

- Lamb, Alastair (1964), The China-India border, Oxford University Press

- Lamb, Alastair (1965), "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF), The Australian Year Book of International Law: 37–52, doi:10.1163/26660229-001-01-900000005

- Lamb, Alastair (1989), Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: a history of imperial diplomacy, Roxford Books, ISBN 9780907129035

- Lange, Diana (2017), "Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area between Western Tibet, Ladakh, and Spiti", Revue d'Études Tibétaines,The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present

- McKay, Alex (2015), Kailas Histories: Renunciate Traditions and the Construction of Himalayan Sacred Geography, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-30618-9

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1 – via archive.org

- Petech, Luciano (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D. (PDF), Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente – via academia.edu

- Rao, Gondker Narayana (1968), The India-China Border: A Reappraisal, Asia Publishing House

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969), Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger – via archive.org

External links

- Demchok Western Sector (Chinese claim), OpenStreetMap

- Demchok Eastern Sector (Indian claim), OpenStreetMap