Rheged

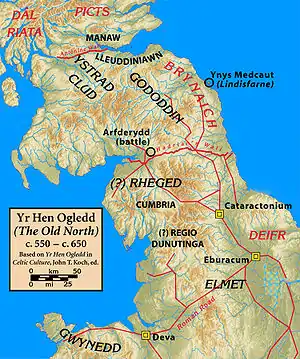

Rheged (Welsh pronunciation: [ˈr̥ɛɡɛd]) was one of the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"), the Brittonic-speaking region of what is now Northern England and southern Scotland, during the post-Roman era and Early Middle Ages. It is recorded in several poetic and bardic sources, although its borders are not described in any of them. A recent archaeological discovery suggests that its stronghold was located in what is now Galloway in Scotland rather than, as was previously speculated, being in Cumbria. Rheged possibly extended into Lancashire and other parts of northern England. In some sources, Rheged is intimately associated with the king Urien Rheged and his family.[1] Its inhabitants spoke Cumbric, a Brittonic dialect closely related to Old Welsh.[2]

Kingdom of Rheged | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.500–c. 600 | |||||||||||

Yr Hen Ogledd (The Old North) c. 550 – c. 650. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Carlisle | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

• | Meirchion Gul | ||||||||||

• | Cynfarch Oer | ||||||||||

• | Urien | ||||||||||

• | Owain mab Urien | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | United Kingdom | ||||||||||

Etymology

The origin of the name Rheged has been described as "problematic".[3] One Brittonic-language solution is that the name may be a compound of rö-, a prefix meaning "great", and cę:d meaning "wood, forest" (c.f. Welsh coed) although the expected form in Welsh would be *Rhygoed. If association of the name with cę:d is correct, the prefix may be rag-, meaning "before, adjacent to, opposite". Derivation from the element reg, which with the suffix -ed has connotations of "generosity", is another possibility.[3]

Location

The name Rheged appears regularly as an epithet of Urien (a late 6th-century king of Rheged) in a number of early Welsh poems and royal genealogies. His victories over the Anglian chieftains of Bernicia in the second half of the 6th century are recorded by Nennius and celebrated by the bard Taliesin, who calls him "Ruler of Rheged". He is thus placed squarely in the North of Britain and perhaps specifically in Westmorland when referred to as "Ruler of Llwyfenydd" (identified with the Lyvennet Valley).[4] Later legend associates Urien with the city of Carlisle (the Roman Luguvalium), only twenty-five miles away; Higham suggests that Rheged was "broadly conterminous with the earlier Civitas Carvetiorum, the Roman administrative unit based on Carlisle". Although it is possible that Rheged was merely a stronghold, it was not uncommon for sub-Roman monarchs to use their kingdom's name as an epithet. It is generally accepted, therefore, that Rheged was a kingdom covering a large part of modern Cumbria.

Place-name evidence, e.g., Dunragit (possibly "Fort of Rheged")α suggests that, at least in one period of its history, Rheged included Dumfries and Galloway. Recent archaeological excavations at Trusty's Hill, a vitrified fort near Gatehouse of Fleet, and the analysis of its artefacts in the context of other sites and their artefacts have led to claims that the kingdom was centred on Galloway early in the 7th century.[5][6]

Interpretations of another place-name, with even less certainty, indicate that Rheged could also have reached as far south as Rochdale in Greater Manchester, recorded in the Domesday Book as Recedham. The River Roch on which Rochdale stands was recorded in the 13th century as Rached or Rachet.[7] Such names may derive from Old English reced "hall or house".[8] However, no other place names originating from this Old English element exist, which makes this derivation unlikely.[9] If they are not of English origin, these place-names may incorporate the element 'Rheged' precisely because they lay on or near its borders. Certainly Urien's kingdom stretched eastward at one time, as he was also "Ruler of Catraeth" (Catterick in North Yorkshire).

Kings of Rheged

The traditional royal genealogy of Urien and his successors traces their ancestry back to Coel Hen (considered by some to be the origins of the Old King Cole of folk tradition),[10][11] who is considered by many to be a mythical figure; if he has some historicity, he may have ruled a considerable part of the North in the early 5th century. All of those listed below may have ruled in Rheged, but only three of their number can be verified from external sources:

- Meirchion Gul, father of Cynfarch

- Cynfarch Oer (Cynfarch the Dismal), also known as Cynfarch fab Meirchion and Cynfarch Gul, father of Urien

- Urien Rheged, (c. 550 – 590), about whom survive eight songs of Taliesin

- Owain, also celebrated for having fought the Bernicians; son of Urien

There are two possible later kings of Rheged:

- Rhun, said to have been a son of Urien. He is recorded in Welsh sources as having baptised Edwin of Northumbria, however, he may merely have stood sponsor at the baptism, thus becoming Edwin's godfather.[12]

- Royth (Rhaith - meaning 'Justice' in Welsh), son of Rhun, and possibly the last king of Rheged.[13]

Southern Rheged

A second royal genealogy exists for a line, perhaps of kings, descended from Cynfarch Oer's brother: Elidir Lydanwyn. According to Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd Elidir's son, Llywarch Hen, was a ruler in North Britain in the 6th century.[14] He was driven from his territory by princely in-fighting after Urien's death and was perhaps in old age associated with Powys. However, it is possible, because of internal inconsistencies, that the poetry connected to Powys was associated with Llywarch's name at a later, probably 9th century, date.[15] Llywarch is referred to in some poems as king of South Rheged, and in others as king of Argoed, suggesting that the two regions were the same. Searching for Llywarch's kingdom has led some historians to propose that Rheged may have been divided between sons, resulting in northern and southern successor states. The connections of the family of Llywarch and Urien with Powys has suggested to some, on grounds of proximity, that the area of modern Lancashire may have been their original home.[16]

End of Rheged

After Bernicia united with Deira to become the kingdom of Northumbria, Rheged was annexed by Northumbria, some time before AD 730. There was a royal marriage between Prince (later King) Oswiu of Northumbria and the Rhegedian princess Rieinmelth, granddaughter of Rum (Rhun), probably in 638, so it is possible that it was a peaceful takeover, both kingdoms being inherited by the same man.[17][18]

After Rheged was incorporated into Northumbria, the old Cumbric language was gradually replaced by Old English, Cumbric surviving only in remote upland communities. Around the year 900, after the power of Northumbria was destroyed by Viking incursions and settlement, large areas west of the Pennines fell without apparent warfare under the control of the British Kingdom of Strathclyde, with Leeds recorded as being on the border between the Britons and the Norse Kingdom of York. This may have represented the political assertion of lingering British culture in the region.[19] The area of Cumbria remained under the control of Strathclyde until the early 11th century when Strathclyde itself was absorbed into the Scottish kingdom. The name of the people, whose modern Welsh form is Cymry has, however, survived in the name of Cumberland and now Cumbria; it probably derives from an old Celtic word *Kombroges meaning "fellow countrymen".

Discovery of a lost stronghold of Rheged

Previously, Rheged was assumed to have been centred somewhere in Cumbria, northwest England. However, in 2012 archaeologists found evidence at Trusty's Hill near the town of Gatehouse of Fleet, in Galloway, southwest Scotland, suggesting that the site may in fact have been Rheged's capital c. 600 AD. The discovery was announced to the public in January 2017 and the site is still under excavation.

One of the lead researchers, Ronan Toolis, stated that their findings revealed structural ruins atop the hill. These originally belonged to a fortification system with a timber-reinforced stone rampart where the main fortification was supplemented by smaller defensive works along the low-lying slopes. According to Toolis, this suggests the presence of a royal stronghold of the period: "This is a type of fort that has been recognized in Scotland as a form of high status secular settlement of the early medieval period. The evidence makes a compelling case for Galloway being the core of the kingdom of Rheged."[20][21]

Genetic legacy

According to the University of Oxford's People of the British Isles project, the original population of Rheged has left a distinct genetic heritage amongst the people of Cumbria. The research compared the DNA of over 2000 people across the British Isles whose grandparents were all born within 50 miles (80 km) of each other, and found a number of cases, including Rheged, where genetic clusters of people matched the location of historical kingdoms (other examples included Bernicia and Elmet).[22]

Notes

- ^α but see: Clarkson, T. J., The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland, John Donald, 2010, p. 71: "Archaeologists are extremely sceptical that this was a site occupied in Early Historic times, still less that it was a royal residence. Such scepticism raises serious doubts about the usual derivation of the place-name Dunragit which may in fact be a red herring. It has been suggested that the second element could be Gaelic reichet rather than Old Welsh Reget, and that the place was so named by the Gall Gaidhil, 'foreign Gaels', who colonised Galloway in the Viking period." For Gaelic re(i)chet, cf. the Old Irish place name Mag Roichet/Rechet (Modern Irish Maigh Reichead), now Morett, country Laois, Ireland.[23]

References

- Koch 2006, p. 1498.

- Jackson 1953, p. 9.

- James, Alan. "The Brittonic Language in the Old North" (PDF). Scottish Place Name Society.

- Williams 1960

- Toolis, R; Bowles, C (2016). The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged: The Discovery of a Royal Stronghold at Trusty's Hill, Galloway, Oxbow Books Limited.

- "Long-lost Dark Age kingdom unearthed in Scotland".

- Williams 1972, p. 82.

- Ekwall, Eilert, The place-names of Lancashire, Manchester University Press, 1922, p. 55.

- Clarkson, T. J., The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland, John Donald, 2010, p. 72.

- Harbus, A. (2002) Magnus Maximus and the Welsh Helena in Helena of Britain in Medieval Legend, Boydell & Brewer, p. 54

- Ford, P.K. (1970) Llywarch, Ancestor of Welsh Princes, Speculum, Vol. 45, No. 3, p. 443 - This author argues that the term hen in the context of early Welsh genealogies has a primary meaning of "heroic ancestor", rather than that the possessor of the epithet necessarily lived to a great age.

- Corning, Caitlin (2000) The Baptism of Edwin, King of Northumbria: A New Analysis of the British Tradition, Northern History, 36:1, 5-15, DOI: 10.1179/007817200790178030

- Andrew Breeze (2013) Northumbria and the Family of Rhun, Northern History, 50:2, pp. 170-179, DOI: 10.1179/0078172X13Z.00000000039

- Chadwick 1959, p. 121.

- Chadwick 1973, pp. 88–89.

- Chadwick & Chadwick 1940, p. 165.

- Jackson, K.H. (1955) The Britons in Southern Scotland, Antiquity, xxix, pp. 77–88

- Lewis, Helen (1989) Whose Cultural Heritage? Etifeddiaeth Ddiwylliannol i Bwy?, English in Education, Taylor & Francis

- Kapelle 1979, p. 34.

- Ronan Toolis, The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged at GUARD Archaeology (Glasgow, Scotland) 21 January 2017; co-authored by Christopher Bowles (Scottish borders council archaeologist)

- Quote taken from report by: Dattatreya Mandal in 'Realm of History' online on 25 January 2017. https://www.realmofhistory.com/2017/01/25/lost-kingdom-rheged-discovered-britain/

- "People of the British Isles: Population Genetics". www.peopleofthebritishisles.org. University of Oxford. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

Several of the other genetic clusters show similar locations to the tribal groupings and kingdoms around at the time of the Saxon invasion (from the 5th century), suggesting that these tribes and kingdoms may have maintained a regional identity for many centuries. For example the Cumbrian cluster corresponds well to the kingdom of Rheged, West Yorkshire to the Elmet and Northumbria to the Bernicia. The existence of these largely quite well separated clusters suggests a remarkable stability of the British people over quite long periods of time.

- Williams, Ifor, “The poems of Llywarch Hen [Sir John Rhŷs Memorial Lecture]”, in: Proceedings of the British Academy, vol. 18, 1932, pp. 269–302 (p. 292).

Sources and further reading

- Chadwick, H.M. (1959). Cambridge Studies in Early British History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chadwick, H.M.; Chadwick, N.K. (1940). The Growth of Literature. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chadwick, N.K (1973) [1958]. Studies in the Early British Church. North Haven, CT: Archon Books. ISBN 978-0-208-01315-6.

- Jackson, Kenneth (1953). Language & History in Early Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Kapelle, W.E. (1979). The Norman Conquest of the North: the Region and its Transformation, 1000–1135. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-7099-0040-5.

- Koch, John T, ed. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- McCarthy, Mike (March 2011). "The kingdom of Rheged : a landscape perspective". Northern History. Leeds. 48 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1179/174587011X12928631621159. S2CID 159794496.

- Toolis, R; Bowles, C (2016). The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged: The Discovery of a Royal Stronghold at Trusty's Hill, Galloway. Oxbow Books Limited. ISBN 9781785703119.

- Williams, Ifor (1960). Canu Taliesin Gyda Rhagymadrodd A Nodiadau. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Williams, Ifor, ed. (1972). The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry (3rd [paperback, 1990] ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-0035-0.

Further reading

- Bartrum, P.C. (1966). Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Clarkson, Tim (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906566-18-0.

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (1994) [1993]. Celt and Saxon The Struggle for Britain AD 410–937. London: Constable & Co. ISBN 978-0-09-473260-5.

- Higham, Nick (1986). The Northern Counties to AD 1000. A Regional History of England. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-49276-9.

- Marsden, John (1992). Northanhymbre Saga: History of the Anglo-Saxon Kings of Northumbria. London: Kyle Cathie. ISBN 978-1-85626-055-8.

- Morris, John (1973). The Age of Arthur. Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-0-85033-289-6.

- Morris-Jones, John (1918). "Y Commrodor". XXVIII. London: The Society of Cymmrodorian.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Toolis, R; Bowles, C (2016). The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged: The Discovery of a Royal Stronghold at Trusty's Hill, Galloway. Oxbow Books Limited. ISBN 9781785703119.

- Williams, Ifor (1935). Canu Llywarch Hen. Gyda Rhagymadrodd a Nodiadau. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.