Knight-errant

A knight-errant[1] (or knight errant[2]) is a figure of medieval chivalric romance literature. The adjective errant (meaning "wandering, roving") indicates how the knight-errant would wander the land in search of adventures to prove his chivalric virtues, either in knightly duels (pas d'armes) or in some other pursuit of courtly love.

Description

The knight-errant is a character who has broken away from the world of his origin, in order to go off on his own to right wrongs or to test and assert his own chivalric ideals. He is motivated by idealism and goals that are often illusory.[3] In medieval Europe, knight-errantry existed in literature, though fictional works from this time often were presented as non-fiction.[4][5]

The template of the knight-errant were the heroes of the Round Table of the Arthurian cycle such as Gawain, Lancelot, and Percival. The quest par excellence in pursuit of which these knights wandered the lands is that of the Holy Grail, such as in Perceval, the Story of the Grail written by Chrétien de Troyes in the 1180s.

The character of the wandering knight existed in romantic literature as it developed during the late 12th century. However, the term "knight-errant" was to come later; its first extant usage occurs in the 14th-century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[6] Knight-errantry tales remained popular with courtly audiences throughout the Late Middle Ages. They were written in Middle French, Middle English, and Middle German.

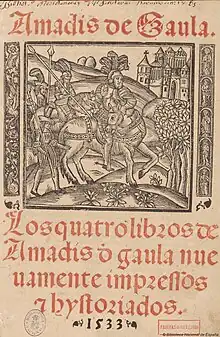

In the 16th century, the genre became highly popular in the Iberian Peninsula; Amadis de Gaula was one of the most successful knight-errantry tales of this period. In Don Quixote (1605), Miguel de Cervantes burlesqued the romances and their popularity. Tales of knight-errantry then fell out of fashion for two centuries, until they re-emerged in the form of the historical novel in Romanticism.

Romance

A knight-errant typically performed all his deeds in the name of a lady, and invoked her name before performing an exploit. In more sublimated forms of knight-errantry, pure moralist idealism rather than romantic inspiration motivated the knight-errant (as in the case of Sir Galahad). Such a knight might well be outside the structure of feudalism, wandering solely to perform noble exploits (and perhaps to find a lord to give his service to), but might also be in service to a king or lord, traveling either in pursuit of a specific duty that his overlord charged him with, or to put down evildoers in general. This quest sends a knight on adventures much like the ones of a knight in search of them, as he happens on the same marvels. In The Faerie Queene, St. George is sent to rescue Una's parents' kingdom from a dragon, and Guyon has no such quest, but both knights encounter perils and adventures.

In the romances, his adventures frequently included greater foes than other knights, including giants, enchantresses, or dragons. They may also gain help that is out of ordinary. Sir Ywain assisted a lion against a serpent, and was thereafter accompanied by it, becoming the Knight of the Lion. Other knights-errant have been assisted by wild men of the woods, as in Valentine and Orson, or, like Guillaume de Palerme, by wolves that were, in fact, enchanted princes.

In modern literature

The protagonist of Cormac McCarthy's novel All the Pretty Horses, John Grady Cole, is said to be based specifically on Sir Gawain, of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Both characters share a number of aspects and traits; both are rooted in the myths of a past that no longer exists, and both live by codes of conduct from a previous era.[7]

Don Quixote is an early 17th-century parody of the genre, in reaction to the extreme popularity which late medieval romances such as Amadis de Gaula came to enjoy in the Iberian Peninsula in the 16th century.

In Jean Giraudoux's play Ondine, which starred Audrey Hepburn on Broadway in 1954, a knight-errant appears, during a storm, at the humble home of a fisherman and his wife.[8]

A depiction of knight-errantry in the modern historical novel is found in Sir Nigel by Arthur Conan Doyle (1906).

The knight-errant stock character became the trope of the "knight in shining armour" in depiction of the Middle Ages in popular culture, and the term came to be used also outside of medieval drama, as in The Dark Knight as a title of Batman.

In the epic fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire, there is a class of knights referred to as Hedge Knights. A Hedge Knight is a wandering knight without a master, and many are quite poor. Hedge knights travel the length and breadth of Westeros looking for gainful employment, and their name comes from the propensity to sleep out in the open air or in forests when they cannot afford lodging. The life of a hedge knight is depicted in the Tales of Dunk and Egg.

Bogatyrs of Kievan Rus'

East Slavic bylina (epic poetry) feature bogatyrs, knights-errant who served as protectors of their homeland, and occasionally as adventurers. Some of them are presumed to be historical figures, while others are fictional and possibly descend from Slavic mythology. Most tales about bogatyrs revolve around the court of Vladimir I of Kiev. Three popular bogatyrs—Ilya Muromets, Dobrynya Nikitich and Alyosha Popovich (famously painted by Victor Vasnetsov)—are said to have served him.

In East Asian cultures

Youxia, Chinese knights-errant, traveled solo protecting common folk from oppressive regimes. Unlike their European counterpart, they did not come from any particular social caste and were anything from soldiers to poets. There is even a popular literary tradition that arose during the Tang dynasty which centered on slaves who used supernatural physical abilities to save kidnapped damsels in distress and to swim to the bottom of raging rivers to retrieve treasures for their feudal lords (see Kunlun Nu).[9][10] A youxia who excels or is renowned for martial prowess or skills is usually called wuxia.

In Japan, the expression musha shugyō described a samurai who, wanting to test his abilities in real life conditions, would travel the land and engage in duels along the way.

References

- As plural, knights-errant is most common, although the form knights-errants is also seen, e.g. in the article Graal in James O. Halliwell, Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words (1847).

- "Knight errant." The Canadian Oxford Dictionary. Ed. Barber, Katherine: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- McGilchrist, Megan Riley. “The Ties that Bind”. Monk, Nicholas, editor. Intertextual and Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cormac McCarthy: Borders and Crossings. Routledge, 2012. p. 24. ISBN 978-1136636066

- Daniel Eisenberg, "The Pseudo-Historicity of the Romances of Chivalry", Quaderni Ibero-Americani, 45–46, 1974–75, pp. 253–259.

- Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi, Historical View of the Literatures of the South of Europe, trans. Thomas Roscoe, 4th edition, London, 1885–88, Vol. I, pp. 76–79.

- Sir Gawain arrives at the castle of Sir Bercilak de Haudesert after long journeys, and Sir Bercilak goes to welcome the "knygt erraunt." The Maven's Word of the Day: Knight Errant

- McGilchrist, Megan Riley. "The Ties that Bind". Monk, Nicholas, editor. Intertextual and Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cormac McCarthy: Borders and Crossings. Routledge, 2012. p. 24. ISBN 9781136636066

- Jean Giraudoux Four Plays. Hill and Wang. 1958. p. 175

- Liu, James J.Y. The Chinese Knight Errant. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1967 ISBN 0-226-48688-5

- .Snow, Philip. The Star Raft: China's Encounter With Africa. Cornell Univ. Press, 1989 ISBN 0-8014-9583-0