Garstang and Knot-End Railway

Garstang & Knot-End Rly | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Garstang and Knot-End Railway [sic] was a railway line, between Garstang and Pilling, across the Fylde of Lancashire, England. It was built by local agricultural interests to develop unproductive land. It had been intended to continue to Knott End but ran out of money. It eventually opened in 1870. In 1898 the Knott End Railway (KER) was authorised to continue to Knott End; it opened in 1908. The two companies were associated and the KER acquired the earlier company. The KER was still desperately short of money, and local people who were owed money bought rolling stock to keep the company going.

Salt extraction near Preesall became a dominant industry from 1890, and the railway conveyed some remarkable tonnages of salt (outward) and coal (inward, for power). The passenger service was discontinued in 1930 and the line closed completely in 1965.

Authorisation

In the mid-nineteenth century, the tract of land to the west of Garstang, in the Fylde area of Lancashire, was an unworked expanse of moss. Attempts were made over time to reclaim the land and put it to agricultural use. In 1863, local landowners led by Wilson F France, the Squire of Rawcliffe, promoted a branch line railway. They saw that transport links to market for agricultural produce were essential; their line was to connect Knott End, opposite Fleetwood on the estuary of the River Wyre, by way of Pilling, to Garstang station on the London and North Western Railway[note 1] main line between Preston and Lancaster.[1]

In December 1863, a prospectus was produced for the proposed Garstang and Knot-End Railway. Six directors were named: John Russell, Julian Augustus Tarner, Henry Gardner, Colonel James Bourne, Richard Bennett and James Overend. The prospectus explained that the object was to improve the outlets for agricultural produce by giving easy access to the markets at Preston and in the towns and cities of industrial Lancashire. The line, it claimed, would link up with Yorkshire, Humberside and Newcastle upon Tyne, and could become part of a main artery between the east and west coasts. A harbour might be built at Knott End to rival and even outgrow Fleetwood. Their scheme went to Parliament, where it was opposed by the London and North Western Railway and the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Facing that danger, the promoters now asserted that their line was "a simple and unpretending line, proposed entirely for the accommodation of the local traffic of the district".[2] Accordingly, the Garstang and Knot End Railway was authorised by Act of 30 June 1864. Authorised capital was £60,000; the line would be 11+1⁄2-mile-long (18.5 km).[3][4][5][6][1]

Construction and opening

Immediately the company was in financial difficulty; the Parliamentary Act authorised £60,000 in share capital, but the company was unable to raise the subscriptions required. In December 1867, the only work accomplished had been the making of the formation for the first half mile, and it was decided to abandon plans to build beyond Pilling. Parliamentary approval for an extension of the time allowed for construction was obtained in 1867, and again in 1869, on the latter occasion also allowing a further £40,000 in authorised share capital.[7] Progress was slow, but in 1870 it appeared possible to open the line as far as Pilling. An LNWR engine was hired in to test the track.[2]

The company could not afford to purchase a locomotive, and train services were operated using a hired 0-4-2 saddle tank named Hebe. Four passenger coaches were procured by a group of debenture holders, who formed the Garstang Rolling Stock Company on 12 October 1870 for the purpose.[2][8]

The permanent way consisted of 48 lb rails fastened to longitudinal sleepers, although a portion was laid with 56 lb bridge rails.[8]

At last on 5 December 1870 the line was opened from Garstang & Catterall Junction (the main line station) to Pilling; there were intermediate stations at Garstang Town and Nateby.[2] There was a celebratory dinner at the Royal Oak Hotel, Garstang, on 14 December 1870. The construction had cost £150,000.[1][4][9]

Operation

The train service consisted of nine trains each way between Garstang Junction and Garstang Town, with two (three on market days) proceeding to and from Pilling. After 1875 this was altered to three each way throughout.[8] In the early years, the trains would pick up and set down passengers anywhere on the route; moreover wagons would be left at a convenient place on the line for unloading, detached from the outward train. They would then be "collected" on the train's return journey, and propelled back to Garstang. "It was not uncommon to see a many as five wagons placed at the front of the train in this way."[2]

Trains were mixed (passengers and goods); passengers could board at any point along the line by request. There was no reserve rolling stock, and when Hebe needed repairs in March 1872, the line was closed for two days. The company fell behind with the rental payments for Hebe, and the locomotive was seized by the owners. It was possible to run occasional goods trains afterwards using horse traction, but the passenger service was suspended on 11 March 1872, and goods trains ceased running two weeks later.[4][9][1][8]

A fresh locomotive, an 0-4-0T named Union, was purchased by the debenture holders[note 2] in 1875 and a goods service was resumed on 23 February 1875; passenger services followed on 17 May 1875. A replacement engine, Farmer's Friend, was acquired in December of that year. It became known locally as the Pilling Pig on account of the squeal made by its whistle. Subsequently, this name was given to all engines and was often used to refer to the railway itself. The company later acquired another engine, an 0-6-0 saddle tank name Farmer's Friend, which started work the following year.[3][4][10][1][8]

Receivership

In 1878 the railway was placed in the hands of a receiver, as it was unable to meet its financial obligations. However it gradually made progress, and in 1890 it began to pay interest to debenture holders: by 1894 it had paid off its debts.[11][7]

Knott End Railway

In 1894 the company harboured thoughts of continuing to Knott End once again. Eventually, on 12 August 1898, Parliamentary authority was obtained for the Knott End Railway' (KER) to extend the line from Pilling to Knott End. The KER had just as much difficulty in raising capital as its predecessor, and it took ten years to build 4+1⁄2 miles of line.

Continuation of two separate companies was hardly practical, and as completion of the line to Knott End was near, on 1 July 1908 the Knott End Railway Company bought the original Garstang and Knot End Company, and the line opened throughout to passengers from Saturday 1 August 1908.[12] The acquisition of the Garstang company had cost £44,690. The new line cost £19,065, and the transfer of the new locomotive, eight passenger carriages, six wagons and three brake vans, cost £110,000. With miscellaneous charges the complete line of 11 miles and 29 chains had cost £179,991.[7] In 1913, 91,918 passengers were carried. In 1920 a steam railmotor was hired in from the London and North Western Railway; it operated the passenger service until that was withdrawn.[1][13]

Personal view in 1908

T R Perkins visited the line in 1908, before the extension to Knot End was open. He observed that there was "a considerable haulage of goods and coal, together with that of military requirements for an artillery camp in the neighbourhood of Knot-End. Several guns for the camp, which had just arrived by train, were standing in the station yard at Pilling at the time of our visit." Perkins was told that receipts for the preceding half year were £2,117 and expenditure £1,208. The rolling stock, he found, consisted of two locomotives, six passenger carriages, and 41 goods vehicles. Two of the carriages had recently been purchased from the Mersey Railway and were not yet in service. The other four carriages had been in use on the line since the beginning. They were reported to be the first examples in Great Britain of the "corridor coach" (referred to nowadays as open saloon coaches). They were six wheelers, with the body carried very low, and entry was from end platforms, the seats being arranged either side of a central gangway. The automatic brake was not used.[8]

Perkins explained the acquisition of the locomotive "Farmer's Friend":

This engine was obtained by an association of residents near the railway, to whom the closing of the line had been a great inconvenience; having formed themselves into a limited liability company, "The Garstang Engine Company", they ordered the engine from Messrs Hudswell, Clark & Co. of Leeds, and leased it to the railway for 14 years at 10 per cent. on cost price. Before the lease expired, however, the railway purchased the locomotive from the lessors, and it continued to work upon the line until 1900, when it was sold and replaced by a new engine, "New Century"... In 1883 the "Hope" was purchased by the same company and leased to the [railway] company on similar terms, but does not appear to have been taken over, as we find that, on the expiration of the lease, a new engine, the "Jubilee Queen" was purchased by the railway... This locomotive was much more powerful than any previously used on the line... The "New Century", purchased three years later, is precisely similar, but cost considerably more.[8]

Traffic after completion of the extension

The extension to Knott End enabled a new traffic, moss litter, to be carried. Moss litter was extensively used as bedding for animals. In 1909 the company carried 55 tons of the traffic, but by 1916 this reached 6,854 tons. After that date the volume declined steeply, largely due to road motor competition. In 1909 beer was carried: 356 tons were conveyed, but that traffic too quickly declined.

A buoyant traffic that transformed the fortunes of the branch line was salt. The United Alkali Company built a large works near Preesall: in its early period, in 1909 55 tons of salt were carried by the railway. In April 1912 United Alkali opened a branch railway siding 1+1⁄2 miles long from near Knott End. In 1913 there were 7,916 tons conveyed by rail. In 1920 the total was 53,416 tons. The United Alkali works required considerable volumes of coal, and 9,244 tons were brought in during the year 1911, rising to 24,135 tons in 1920. The Alkali works had a mineral railway system with a wharf on the river, and these tonnages may have had short transits by rail.[note 3][7][1]

Preesall salt works

Extensive salt deposits near Preesall were discovered in 1872, and in time this led to industrial extraction from 1885 by the Fleetwood Salt Company, which sold to the Salt Union Limited in 1888, which sold to United Alakali Ltd in 1890. The salt was extracted in the form of brine (a saturated solution of salt in water). Due to the absence of any transport facilities capable of handling the volume of salt, an area on the west side of the river, at Burn Naze, south of Fleetwood, was selected as the location of a purifying works, operational from 1889. The brine was transported to Burn Naze by a ten-inch steel pipe. From about 1891 the system of extraction was changed to dry mining. Technical difficulties resulted in the mine closing in 1930.

Grouping of the railways

Compulsory grouping of the railways took place in 1922 - 1923 under the Railways Act 1921. A new London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) was established and the Knott End Railway was absorbed into the LMS; it was its smallest constituent in the grouping process. Four steam engines as well as the railmotor were carried into LMS stock.[1][4][14] The settlement gave holders of 4% debenture stock an equivalent LMS stock that would give 3%; this may have been a recognition of the uncertain and now-declining commercial position of the Knott End company. Ordinary shares were cancelled, as were the arrears of interest on debenture stock.[7]

In the last full year before the grouping, 1922, the line carried 77,579 passenger journeys and 69,535 tons of goods. The total revenue was £12,815 and the expenditure £11,583.[7]

Some time after 1925 the Moss Litter Works near Cogie Hill crossing closed.

Closure

The line closed to passenger traffic from 31 March 1930.[3][4][15][13][16]

The line continued to be used for goods for the time being, but the section from Knott End to Pilling was closed completely on 13 November 1950, followed by the Pilling to Garstang Town section, which closed on 31 July 1963,[3] The short section to Garstang Town continued in use for two more years until closure came on 16 August 1965.[17][13]

One mile (1.6 km) of the route near Knott End is now a footpath. Several crossing keepers' cottages along the line still stand as private residences.[17]

Locomotives

- 1870: Black, Hawthorn 0-4-2ST Hebe

- 1874: Manning Wardle 0-4-0ST Union

- 1875: Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0ST Farmer's Friend[18] (alias "Pilling Pig")

- 1885: Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0ST Hope

- 1897: Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0ST Jubilee Queen

- 1900: Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0ST New Century

- 1908: Manning Wardle 0-6-0T Knott End

- 1909: Manning Wardle 2-6-0T Blackpool[3][4] (fitted with Isaacson's patent valve gear)

Location list

- Garstang & Catterall; main line station opened 26 June 1840 as Garstang; renamed Garstang & Catterall 1881; alternative of Garstang Junction also used; closed 3 February 1969;

- Garstang Town; opened 5 December 1870; opened 5 December 1870 as Garstang; closed 11 March 1872; reopened 17 May 1875; renamed Garstang Town 2 June 1924; closed 31 March 1930;

- Winmarleigh; opened 5 December 1870; closed 11 March 1872; reopened 17 May 1875; renamed Nateby 1 January 1902; closed 31 March 1930;

- Cogie Hill; opened 5 December 1870; closed 11 March 1872; reopened 17 May 1875; closed 31 March 1930;

- Cockenham Cross; opened 5 December 1870; closed 11 March 1872; reopened 17 May 1875; closed 31 March 1930;

- Garstang Road Halt; opened October 1923; closed 31 March 1930;

- Pilling; opened 5 December 1870; closed 11 March 1872; reopened 17 May 1875; closed 31 March 1930; occasionally referred to locally as Stakepool in early days;

- Carr Lane; opened July 1921; closed 31 March 1930;

- Preesall; opened 3 August 1908; closed 31 March 1930;

- Knott End; opened 3 August 1908; closed 31 March 1930.[19][20]

Gallery

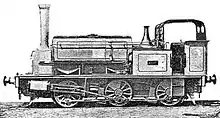

Jubilee Queen, 1897

Jubilee Queen, 1897 A restored Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0, now named "The Pilling Pig", on display at Pilling in 2009

A restored Hudswell Clarke 0-6-0, now named "The Pilling Pig", on display at Pilling in 2009

Notes

- The line belonged to the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway and was worked by the LNWR.

- Debenture holders were persons or institutions which had lent money to the company as opposed to taking shares; no doubt seeing that bankrupting the company would lose them all their investment, they thought the purchase of Union would enable the company to generate some profit and get their money back.

- The tonnages are quoted by respected authors, but need to be read cautiously, and may refer to rail use on the Fleetwood side of the River Wyre. The salt works was on the west side of the river, and any rail transit to ultimate destination would not have involved the Garstang line. After the discontinuation of the pipeline, the dry salt was probably taken over the Wyre from Preesall Wharf, without using the Garstang line. Inwards coal may well have come over the line, but equally well may have come in to Preesall Wharf by coaster. If these traffics used the Preesall works mineral line, it would be misleading to regard them as running on the Garstang and Knott End branch line.

References

- McLoughlin

- Walmsley

- Wells

- Walmesley

- Suggitt, p.28

- Grant, pages 238 and 239

- Sekon

- Perkins

- Suggitt, pp.28–30

- Suggitt, pp.30–32

- Marshall

- Lancashire Evening Post, 29 July 1908 [Fleetwood Chronicle, 31 July 1908, explained that a VIPs' ceremonial train and a public excursion had run on 30 July, which is usually (but erroneously) given as the opening date]

- Gemmell

- Suggitt, p.32

- Ashworth (1930), p.433

- Lancashire Evening Post, 29 March 1930

- Suggitt, p.34

- Perkins (1908); p. 73

- Quick

- Cobb

Sources

- Ashworth, J.E.N. (1930) "My Last Trip on the Knott End Railway", The Railway Magazine, 66 (396), p. 432–433

- Bairstow, Martin (2001) Railways of Blackpool and the Fylde, Martin Bairstow Publications, ISBN 1-871944-23-6, p. 40–44

- Cobb, Col M H, The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 2002

- Conolly, W. Philip [1957] (1997) Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer, 5th Ed., Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-0320-3, p. 24

- Edwards, Margaret, The Garstang - Knott End Railway, Lancaster Museum Monographs, 1975

- Gammell, C. J., LMS Branch Lines, OPC, 1980, page 23

- Grant, Donald J, Directory of the Railway Companies of Great Britain, Matador Publishers, Kibworth Beauchamp, 2017, ISBN 978 1785893 537

- Kirkman, Richard & van Zeller, Peter (1991) Rails to the Lancashire Coast, Dalesman Books, ISBN 1-85568-027-0, p. 50–52

- Marshall, John, Forgotten Railways: volume 9: North West England, David St John Thomas, Nairn, 1992, ISBN 0 946537 71 2, page 77

- McLoughlin, Barry, Railways of the Fylde, Carnegie Publishing, Preston, 1992, ISBN 0-948789-84-0, pages 27 to 30

- Perkins, T R, The Garstang & Knot-End Railway, The Railway Magazine, January 1908, 22, p. 72–77

- Quick, Michael, Railway Passenger Stations in England, Scotland and Wales: A Chronology, the Railway and Canal Historical Society, Richmond, Surrey, fifth (electronic) edition, 2019

- Sekon, G A, The Knott End Railway, in the Railway Magazine, December 1924* Suggitt, Gordon (2004) Lost Railways of Lancashire, Newbury, Countryside Books, ISBN 1-85306-801-2

- Vanless, V, Preesall Salt Mines, British Mining No 11, of the Northern Mind Research Society, Sheffield, 1979, pages 38 to 43

- Walmesley, Frank K (1959) "The Garstang & Knot-End Railway", The Railway Magazine, 105 (704: December), p. 859–864

- Wells, Jeffrey (1993) "The Pig and Whistle railway: a Lancashire backwater", BackTrack, 7, pp. 257–265, summary accessed online 4 September 2007