Koch–Pasteur rivalry

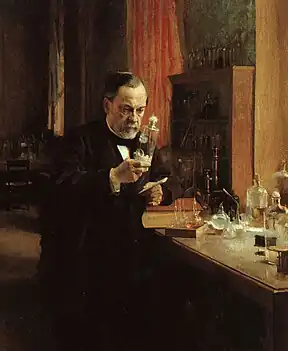

The French Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and German Robert Koch (1843–1910) are the two greatest figures in medical microbiology and in establishing acceptance of the germ theory of disease (germ theory).[1] In 1882, fueled by national rivalry and a language barrier, the tension between Pasteur and the younger Koch erupted into an acute conflict.[1]

Pasteur had already discovered molecular chirality, investigated fermentation, refuted spontaneous generation, inspired Lister's introduction of antisepsis to surgery, introduced pasteurization to France's wine industry, answered the silkworm diseases blighting France's silkworm industry, attenuated a Pasteurella species of bacteria to develop vaccine to chicken cholera (1879), and introduced anthrax vaccine (1881).[1]

Koch had transformed bacteriology by introducing the technique of pure culture, whereby he established the microbial cause of the disease anthrax (1876), had introduced both staining and solid culture plates to bacteriology (1881), had identified the microbial cause of tuberculosis (1882), had incidentally popularized Koch's postulates for identifying the microbial cause of a disease, and would later identify the microbial cause of cholera (1883).

Although Koch had briefly and, thereafter, his bacteriological followers regarded a bacterial species' properties as unalterable,[2] Pasteur's modification of virulence to develop vaccine demonstrated this doctrine's falsity.[1] At an 1882 conference, a mistranslated term from French to German during Pasteur's lecture triggered Koch's indignation, whereupon Koch's two bacteriologist colleagues, Friedrich Loeffler and Georg Gaffky, published denigration of the entirety of Pasteur's research on anthrax since 1877.[1]

Tensions between France and Germany

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the University of Strasbourg, located in Alsace, where he married the daughter of the rector. Jean Baptiste Pasteur, the only son of Louis and Marie Pasteur, was a soldier in the Franco-Prussian War. The tone set by this war contributed to the rivalry between Koch and Pasteur.[1] The "German Problem", as Germany increasingly gained scientific, technological, and industrial dominance, fed tensions among European nations.[3] Germ theory's applications were embedded in the heightening quest by France, Germany, Britain, and Italy to colonize Africa and Asia with the aid of tropical medicine,[4] a new variant of colonial medicine,[5] while medical scientists in respective nations vied to lead advances.[6]

Koch's bacteriology and anthrax

.jpg.webp)

In 1863, influenced by Pasteur's research on fermentation, fellow Frenchman Casimir Davaine mostly explained the cause of anthrax, but Davaine's explanation was opposed by those who opposed the idea that infection with a microorganism could explain it. In 1840, Jakob Henle had proposed microorganism infections caused diseases, and in 1875 German botanist Ferdinand Cohn weighed in on a controversy in microbiology by declaring that the elementary unit was the cell and that each form of bacteria was constant and naturally divided from the other forms. Influenced by Henle and by Cohn, Koch developed a pure culture of the bacteria described by Davaine, traced its spore stage, inoculated it into animals, and showed it caused anthrax. Pasteur called this a "remarkable achievement".[7] In pure culture, bacteria tend to keep constant traits, and Koch reported having already observed constancy.

Pasteur undertook investigation, yet gave much credit to Davaine. Meanwhile, Pasteur's researchers always reported variation in their cultures. In 1879, Henri Toussaint identified a bacterial species involved in chicken cholera and named the genus in honor of Pasteur, Pasteurella. In Pasteur's laboratory, a culture of Pasteurella multocida was left out over a weekend exposed to air, and Pasteur and Emile Roux noticed upon return to the laboratory that its virulence to chickens was diminished. Pasteur applied the discovery to develop chicken cholera vaccine, introduced in a public experiment, an empirical challenge to the stance of Koch's bacteriologists that bacterial traits were unalterable.[1]

Pasteur's attenuation and vaccines

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "Bacillus anthracis of the Germans".[1] In July 1880 Toussaint reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible.[8] Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it.[8] Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues.[8][9] (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)[8][10][11]

Microbe hunting, cholera, and public health

In 1883, responding to a cholera epidemic in Alexandria, Egypt, both Pasteur and Koch sent missions vying to identify its cause. Koch returned victorious, whereupon Pasteur switched research direction and began development of rabies vaccine.[6] As to public health, Koch's bacteriologists feuded with Max von Pettenkofer—whose miasmatic theory claimed the bacteria was but one causal factor among at least several—but von Pettenkoffer stubbornly opposed water treatment, and the massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg, Germany, in 1892 devastated von Pettenkofer's position, and German public health was grounded on Koch's bacteriology.[12] Meanwhile, Pasteur led introduction of pasteurization in France.

Rabies vaccine and Pasteur Institute

Rabies, uncommon but excruciating and almost invariably fatal, was dreaded. Amid anthrax vaccine's success, Pasteur introduced rabies vaccine (1885), the first human vaccine since Jenner's smallpox vaccine (1796). On 6 July 1885, the vaccine was tested on 9-year old Joseph Meister who had been bitten by a rabid dog but failed to develop rabies, and Pasteur was called a hero.[13] (Even without vaccination, not everyone bitten by a rabid dog develops rabies.) After other apparently successful cases, donations poured in from across the globe, funding the establishment of the Pasteur Institute, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in Paris in 1888.[14]

Pasteur Institute trained military physicians in colonial medicine, although French government soon took over this role.[6] The success of Pasteur's modification of bacterial virulence inspired confidence in the universality of Pasteurian science, though Pasteur's researchers preferred the term microbiology over the term bacteriology.[6] Koch discouraged use of rabies vaccine,[1] whose production later became a premise for opening Pasteur Institutes abroad, as in Shanghai, China.[15] The first overseas Pasteur Institute was opened by Albert Calmette in Saigon in French Indochina in 1891, although Pasteur's nephew Adrien Loir was already planning to open one in Australia.[6]

Tuberculin and Robert Koch Institute

In 1882, Koch reported identification of the tubercle bacillus as the cause of tuberculosis,[16] cementing germ theory. Koch took his research into a new direction—applied research—to develop a tuberculosis treatment and use the profits to found his own research institute, autonomous from government.[17] In 1890 Koch introduced the intended drug, tuberculin, but it soon proved ineffective, and accounts of deaths followed in new press.[18] Amid Koch's reluctance to disclose tuberculin's formula, Koch's reputation sustained damage, but Koch retained lasting acclaim and received the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis".[19] Koch accepted government's offer to direct the Institute for Infectious Diseases (1891), in Berlin, a prestigious position but not the kind of institute that Koch had sought.[17] It was later renamed the Robert Koch Institute, which remains a government organization.

American medicine embraces Koch

The monomorphist doctrine of Koch's bacteriologists suggested public health interventions to eliminate bacteria, whereas Pasteur's acceptance of variation suggested attenuating bacterial virulence in the laboratory to develop vaccines.[1] Although inspired by Pasteur's applications suggesting medicine's potential, American physicians traveled to Germany to learn Koch's bacteriology as basic science,[20] though Pasteur emphasized the fuzzy boundary between basic science and applied science.[1]

From 1876 to 1878, the American William Henry Welch trained in Germany pathology, and in 1879 opened America's first scientific laboratory, a pathology laboratory in Bellevue's medical school in New York.[21] While in Germany, Welch had met John Shaw Billings who had been appointed by Daniel Coit Gilman—the first president of the newly forming Johns Hopkins University—to plan Hopkins' hospital and medical school.[21] Named the medical school's first dean in 1883,[21] Welch promptly traveled for training in Koch's bacteriology, and returned to America eager to transform medicine with the "secrets of nature".[22] Hopkins medical school opened in 1894 with Welch emphasizing Koch's bacteriology,[22] which became the foundation of modern medicine.[1][23]

As "dean of American medicine", William H Welch became the first scientific director of Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901), and appointed his former Hopkins student Simon Flexner the first director of pathology and bacteriology laboratories. Aided by the "Flexner report", published in 1910 while Welch was president of the American Medical Association, Welch's view of science and medicine became the national standard,[24] a transformation of American medical education completed around 1930.[25] As first dean of America's first public health school, founded in 1916 at Hopkins, Welch set the standard for public health, and with Simon Flexner exported the Hopkins model internationally.

Pasteur's image ascends

Although Pasteur died in 1895, eventually over thirty official Pasteur Institutes opened across the globe.[26] Pasteur's team had planned in 1885 to open a rabies-treatment facility in St. Louis, Missouri, and an American Pasteur Institute in New York City, but the plans were abandoned, and America has never hosted an official Pasteur Institute.[26]

A number of American copycats appeared, however, starting with "Chicago Pasteur Institute" in 1890, and "New York Pasteur Institute" in 1891.[26] In 1897 a "Pasteur Institute" opened in Baltimore, in 1900 in Pittsburgh and St. Louis, in 1903 in Ann Arbor and Austin, and in 1904 perhaps in Philadelphia.[26] In 1908, Georgia Department of Public Health opened a "Pasteur Department" in Atlanta, California State Hygienic Laboratory opened a "Pasteur Division" in Berkeley, and a "Pasteur Institute" opened in Washington, D.C.[26]

In 1900, Paul Gibier, the French medical scientist who opened "New York Pasteur Institute", accidentally died, but his nephew, George Gibier Rambaud, continued it on reduced scale until he closed it when US Medical Corps commissioned him overseas in 1918.[26] While MDs ascended in American public health, it was thought that "the greatest contribution of all, the foundation upon which modern sanitary science is built, was made by Pasteur."[27]

Nationalism flares

Koch was celebrated by the American medical community, including by Welch, when at last Koch visited America in 1908. Soon, however, America was influenced by the British and French view that although their denizens appreciated Germany's progress in science and arts, Germany was elitist and dismissive while socially and politically antiquated, so authoritarian and aggressive as to resemble medieval tyranny.[28]

In 1917, when America entered World War I (1914–18), US government seized German-owned property and assets, including Bayer AG's American trademarks and the 80% of Merck & Co's shares owned by George Merck.[29][30] Welch exhibited gratuitous anti-German bias despite the debt of his own career, thus American medicine, to Germany,[31] especially to Koch's bacteriology.[23]

After World War II (1939–45), and more of the "German Problem", Merck & Co became the global leader in vaccinology.

Two legacies

Tuberculin's main use rapidly became in determining M tuberculosis infection—a use remaining till today—but this use soon revealed that in London, 9 of 10 individuals were infected, whereas only 1 in 10 of the infected developed the disease.[32] In 1901 at the London Congress on Tuberculosis, Koch stated on theoretical grounds that M bovis, which infects cows, was not transmissible to humans.[33] British attendees disagreed, and later Theobald Smith and the English Royal Commission empirically established that M bovis was transmissible and could result in human disease.[33] Though widely considered ineffective as treatment, tuberculin might have remained in use for this purpose until the 1940s and maybe had some effectiveness.[34]

Milk pasteurization became popular in America around 1920.[26] In 1921 Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin of Pasteur Institute introduced tuberculosis vaccine, whose virulence of strains varied in the late 1920s.[35] BCG vaccine was not used in the public health of America, which virtually eliminated tuberculosis without it. BCG vaccine's effectiveness preventing tuberculosis remains uncertain,[36] but appears to confer nonspecific survival gains,[36] as perhaps by preventing leprosy, and is a cancer treatment.[37]

Pasteur had highlighted a new threat—microorganisms benign to humans passing among and multiplying in nonhuman animals while gaining new virulence for humans—that is thought to loom and to have approximately materialized with AIDS.[1] Although Koch's postulates are often inapplicable, they remain heuristic, and the authority of "fulfilling Koch's postulates" is still invoked in medical science, though often in modified form,[38] as in the identification of HIV-1 as the cause of AIDS or the identification of SARS coronavirus as the cause of SARS.[39][40][41]

Germ theory's stance that the "germ" was the disease's necessary and sufficient cause—the single factor both required and complete to result in the disease—proved false.[12] Germ theory gradually evolved to include other factors, whereupon germ theory resembled miasmatic theory, which had had to recognize bacteria as a causal factor, and so the two competing explanations merged without true, decisive victor.[12] Twentieth-century philosophy, inspired by revolutions in physics, establishment of molecular biology, and advances in epidemiology, revealed that any claim of a single causal factor both necessary (required) and sufficient (complete), the cause, is untenable.[42][43] French-born microbiologist René Dubos, a biographer of Pasteur, discussed tuberculosis to illustrate disease's social causes and to illustrate the failure of germ theory,[44][45] whose apparent successes were aided by improvements in nutrition and living conditions but sparked scientific research that brought a wealth of new understandings.[46]

References

- Ullmann, Agnes (2007). "Pasteur–Koch: Distinctive Ways of Thinking about Infectious Diseases". Microbe. 2 (8): 383–7. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- Felix Löhnis, "Studies upon the life cycles of the bacteria", Part I: "Review of the literature, 1838–1918", Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1921;61(2):5–335, pp 8, 10–12.

- Lowe John, The Great Powers, Imperialism and the German Problem 1865–1925 (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 195–9.

- Schneider, WH (2009). "Smallpox in Africa during colonial rule". Medical History. 53 (2): 193–227. doi:10.1017/s002572730000363x. PMC 2668906. PMID 19367346.

- Davidovitch, N; Greenberg, Z (2007). "Public health, culture, and colonial medicine: Smallpox and variolation in Palestine during the British Mandate". Public Health Reports. 122 (3): 398–406. doi:10.1177/003335490712200314. PMC 1847484. PMID 17518312.

- Guénel, A (1999). "The creation of the first overseas Pasteur Institute, or the beginning of Albert Calmette's Pastorian career". Medical History. 43 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/s0025727300064693. PMC 1044108. PMID 10885131.

- Mollaret, HH (1996). "Contribution à la connaissance des relations entre Koch et Pasteur" [The relationship between Pasteur and Koch]. La Revue du Praticien (in French). 46 (20): 2396–400. See Trans. E. T. Cohn; B. H. Fasciotto-Dunn; U. Kuhn; D. V. Cohn. "Contribution to the knowledge of relations between Koch and Pasteur".

- Chevallier-Jussiau, Nadine (2010). "Henry Toussaint et Louis Pasteur Une rivalité pour un vaccin" [Henry Toussaint and Louis Pasteur. Rivalry over a vaccine]. Histoire des Sciences Médicales (in French). 44 (1): 55–64. PMID 20527335.

- Koch R & Carter KC, Essays of Robert Koch (New York: Greenwood Press, 1987).

- Geison GL, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995).

- Pasteur, L (2002). "Summary report of the experiments conducted at Pouilly-le-Fort, near Melun, on the anthrax vaccination, 1881". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 75 (1): 59–62. PMC 2588695. PMID 12074483.

- Oppenheimer, G. M.; Susser, E. (2007). "Invited Commentary: The Context and Challenge of von Pettenkofer's Contributions to Epidemiology". American Journal of Epidemiology. 166 (11): 1239–41, discussion 1242–3. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm284. PMID 17934199.

- Trueman C, "Louis Pasteur", History Learning Site, 2000–2011, Web.

- The Institut Pasteur > History. Pasteur Institute. 10 November 2016.

- Yang, Wei; Li, Zhi-ping (2008). "The research works on Shanghai Pasteur Institute". Chinese Journal of Medical History (in Chinese). 38 (2): 92–8. PMID 19125502.

- Koch R (1882), "Die atiologie der tuberkulose", in Schwalbe J, ed, Gesammelte Werke von Robert Koch (Leipzig: Georg Thieme, 1912, orig 1910), pp 428–45.

- Gradmann, C (2000). "Money and microbes: Robert Koch, tuberculin and the Foundation of the Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin in 1891". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 22 (1): 59–79. PMID 11258101.

- "Professor Koch's Treatment of Tuberculosis". The Lancet. 136 (3510): 1239–1241. 1890. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)86145-6.

- Gradmann, C (2001). "Robert Koch and the pressures of scientific research: Tuberculosis and tuberculin". Medical History. 45 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1017/s0025727300000028. PMC 1044696. PMID 11235050.

- Gossel, PP (2000). "Pasteur, Koch and American bacteriology". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 22 (1): 81–100. PMID 11258102.

- Silverman, BD (2011). "William Henry Welch (1850–1934): The road to Johns Hopkins". Proceedings. 24 (3): 236–42. doi:10.1080/08998280.2011.11928722. PMC 3124910. PMID 21738298.

- Benson, KR (1999). "Welch, Sedgwick, and the Hopkins model of hygiene". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 72 (5): 313–20. PMC 2579023. PMID 11049162.

- Maulitz, RC (1982). "Robert Koch and American medicine". Annals of Internal Medicine. 97 (5): 761–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-761. PMID 6753684.

- Tauber, AI (1992). "The two faces of medical education: Flexner and Osler revisited". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 85 (10): 598–602. doi:10.1177/014107689208501004. PMC 1293684. PMID 1433034.

- Beck, Andrew H. (2004). "The Flexner Report and the Standardization of American Medical Education". JAMA. 291 (17): 2139–40. doi:10.1001/jama.291.17.2139. PMID 15126445.

- Pasteur Foundation, "Pasteur Institutes USA: A turn-of-the-century phenomenon" Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine, Remembrance of Things Pasteur, Accessed 5 Sep 2012 on Web.

- Knowles, M (1913). "Public Health Service Not a Medical Monopoly". American Journal of Public Health. 3 (2): 111–22. doi:10.2105/ajph.3.2.111. PMC 1089532. PMID 18008793.

- Charles Sarolea, The Anglo-German Problem, American edn (New York & London: G P Putnam's Sons, 1915), pp 33–6.

- Kirk K W Tyson, Competition in the 21st Century (Boca Raton: CRC Press LLC, 1997), p. 237.

- Ibis Sánchez-Serrano, The World's Health Care Crisis: From the Laboratory Bench to the Patient's Bedside (London: Elsevier, 2011), pp 55–7.

- Roberts, CS (2009). "Bachelors in Baltimore: Mr. Mencken and Dr. Welch". Proceedings. 22 (4): 348–50. doi:10.1080/08998280.2009.11928555. PMC 2760171. PMID 19865510.

- Condrau, F.; Worboys, M. (2008). "Epidemics and infections in nineteenth-century Britain". Social History of Medicine. 22 (1): 165–71. doi:10.1093/shm/hkp002. PMC 2663978.

- Schultz, Myron G. (2011). "Photo quiz". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (3): 547–9. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101881. PMC 3298383. PMID 21392456.

- Cardona, Pere J. (2006). "Robert Koch tenía razón. Hacia una nueva interpretación de la terapia con tuberculina" [Robert Koch was right. Towards a new interpretation of tuberculin therapy]. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (in Spanish). 24 (6): 385–91. doi:10.1157/13089694. PMID 16792942.

- Oettinger, T.; Jørgensen, M.; Ladefoged, A.; Hasløv, K.; Andersen, P. (1999). "Development of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: Review of the historical and biochemical evidence for a genealogical tree". Tubercle and Lung Disease. 79 (4): 243–50. doi:10.1054/tuld.1999.0206. PMID 10692993.

- Roth, AE; et al. (2006). "Beneficial non-targeted effects of BCG—ethical implications for the coming introduction of new TB vaccines". Tuberculosis. 86 (6): 397–403. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2006.02.001. PMID 16901755.

- Brosman, SA (1991). "BCG vaccine in urinary bladder cancer". West J Med. 155 (6): 633. PMC 1003114. PMID 1812634.

- Gradmann, Christoph (2008). "Alles eine Frage der Methode. Zur Historizität der Kochschen Postulate 1840–2000" [A matter of methods: The historicity of Koch's postulates 1840–2000]. Medizinhistorisches Journal (in German). 43 (2): 121–48. doi:10.25162/medhist-2008-0005. PMID 18839931. S2CID 252456478.

- Harden, VA (1992). "Koch's postulates and the etiology of AIDS: An historical perspective". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 14 (2): 249–69. PMID 1342726.

- O'Brien, SJ; Goedert, JJ (1996). "HIV causes AIDS: Koch's postulates fulfilled". Current Opinion in Immunology. 8 (5): 613–8. doi:10.1016/S0952-7915(96)80075-6. PMID 8902385.

- Fouchier, Ron A. M.; Kuiken, Thijs; Schutten, Martin; Van Amerongen, Geert; Van Doornum, Gerard J. J.; Van Den Hoogen, Bernadette G.; Peiris, Malik; Lim, Wilina; et al. (2003). "Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus". Nature. 423 (6937): 240. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..240F. doi:10.1038/423240a. PMC 7095368. PMID 12748632.

- Rothman, Kenneth J.; Greenland, Sander (2005). "Causation and causal inference in epidemiology". American Journal of Public Health. 95: S144–50. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059204. hdl:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059204. PMID 16030331.

- Kundi, Michael (2006). "Causality and the interpretation of epidemiologic evidence". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (7): 969–74. doi:10.1289/ehp.8297. PMC 1513293. PMID 16835045.

- Conrad P, Mirage of genes—sec "Introduction", p. 438, in Conrad P, ed, The Sociology of Health and Illness: Critical Perspectives, 8th edn (New York: Worth Publishers, 2009).

- René J Dubos, Mirage of Health: Utopia, Progress, and Biological Change (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959 / New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987).

- Meeting summary, "Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Global Health & Novel Intervention Strategies" Archived 2011-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Institute of Medicine of National Academies, Apr 2010.