Koggala Lagoon

Koggala Lagoon (Sinhala: කොග්ගල කලපුව Koggala Kalapuwa) is a coastal body of water located in Galle District, Southern Sri Lanka. It is situated near the town of Koggala and adjacent to the southern coast, about 110 km (68 mi) south of Colombo. The lagoon is embellished with eight ecologically rich small islands.

| Koggala Lagoon (Koggala Lake) කොග්ගල කලපුව | |

|---|---|

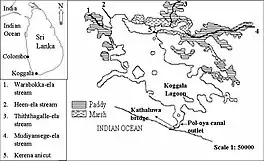

Map of Koggala lagoon with the locations of outlet and major freshwater inflows. Suburb marsh and paddy field areas are shown in different shaded patterns[1] | |

Koggala Lagoon (Koggala Lake) කොග්ගල කලපුව | |

| Location | Galle District, Sri Lanka |

| Coordinates | 6°0′N 80°20′E |

| Type | Lagoon |

| Primary inflows | Warabokka-ela stream (Koggala-oya), Mudiyansege-ela stream, Thithagalla-ela stream, Heen-ela stream |

| Primary outflows | Indian Ocean |

| Catchment area | 55 square kilometres (21 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Sri Lanka |

| Max. length | 4.8 km (3.0 mi) |

| Max. width | 2 km (1.2 mi) |

| Surface area | 7.27 square kilometres (2.81 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 1 metre (3.3 ft) |

| Max. depth | 3.7 metres (12 ft) |

| Surface elevation | Sea level |

| Islands | Mangrove Island (Madol Doova), Cinnaman Island, Kathdoova |

Features and location

The lagoon has a surface area of approximately 7.27 km2 (2.81 sq mi) measuring 4.8 kilometres (3.0 mi) in length and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) in width.[2] The water depth ranges from 1.0 metre (3.3 ft) to 3.7 metres (12 ft).[3] The lagoon is largely rain fed and a number of streams are connected to it. Warabokka-ela stream (Koggala-oya) that enters the lagoon from the north-west is the main freshwater supply.[4] Kerena anicut, which was constructed combining two streams, Mudiyansege-ela stream and Thithagalla-ela stream, is the second largest freshwater inflow.[4] Heen-ela stream contributes a minor to the freshwater inflow[4] In addition to above four streams, Kahanda-ela stream, Gurukanda-ela stream and Thelambu-ela stream are also contributors for freshwater inflows but are presently abandoned with overgrown vegetation.[4] The only outlet of the lagoon is Pol-oya located at the southeast corner; a narrow 300 metres (980 ft) long canal, which connects the lagoon with the Indian Ocean.

The lagoon has a hydro-catchment area of approximately 55 km2 (21 sq mi).2 [5] Various land use practices exist in the catchment, which mainly includes small-scale fishing industry and paddy farming.[6] The Koggala Export Processing Zone (KEPZ), is an industrial area with a surface area of 91 ha (220 acres) located within the catchment area of the lagoon.[4]

Tourism

The Koggala Lagoon is one of the main features for tourists who visit southern coastal areas in Sri Lanka with rich bio diversities and eco systems.[7] The Lagoon is scattered with eight small islands.[8] The islands consist of lush mangrove swamps. Anchored in mud, the mangrove roots are coated with a variety of creatures, including barnacles, oysters and crabs.[9] The dense, intertwining roots serve as nurseries for many fish species. There are seven islands in the lagoon, that can be reached by boat.[8] The most famous of the islands is ‘Madol Doova' (Mangrove Island Sinhala: මඩොල් දූව)’, which is described in detail by Martin Wickramasinghe in his novel, Madol Doova. Motor boats are available to hire to travel across the lagoon.[10] Tourists can witness the varying species of Mangrove, about ten of which are endemic to Sri Lanka. Wildlife of these islands inherited to a wide variety of flora and fauna, like monitor lizards and a number of birds.

In addition to wildlife and the scenery, Kathaluwa Buddhist Temple (Kathaluwa Purvarama Maha Vihara) is one of the main tourist attractions in the lagoon with Kandyan-style paintings dated 19th century.[10] Some images include colonial rulers and strangely Queen Victoria herself to commemorate her support for local Buddhism in the face of British missionary Christianity.[8]

Environmental problems

Destruction of the natural sand bar

The Koggala lagoon was once a paradise for its ecological community. However, human intervention has changed the fate of the lagoon with the destruction of the natural groyne (sand bar) during coastal defense activities in early 1990s.[5] This has been followed by unplanned removal of sand at the Pol-oya outlet near the lagoon mouth. The naturally built sand bar, which was perpendicular to the lagoon mouth controlled the seawater intrusion into the lagoon. With the opening of the lagoon mouth during the rainy season, rapid outflow of water began. However, the flow of seawater into the lagoon during the monsoon and high tides ceased the formation of sand bar again in the dry season. This natural dynamic rhythm causes high seasonal variations in most of the physical and chemical properties of lagoon water.

After the removal of the natural sand barrier, the formation of sand bar shifted towards the “Kathaluwa” bridge (highway bridge) by exposing the bridge to wave attack. Breaching the sand bar became increasingly difficult and erosion close to the bridge posed a risk to the bridge. Subsequently, in 1995, the Southern Provincial Council built a groyne system to protect the bridge from the wave attack. Another groyne was built in 2005 to control the erosion at the west side of the mouth due to prevailing groyne structure. Construction of the groyne provoked concern over local resource users and environmentalists as the lagoon hydrology and water quality showed drastic changes and variations.[5]

Threats to ecology and livelihoods

Due to the increased salinity of the lagoon, the ecological system has also been affected severely. Many freshwater species (Ex; Malpulutta kretseri, Etroplus suratensis) is at the risk of being prone to growth difficulties or they might even face extinction if the breeding grounds are undesirable.[11]

Increased salinity in the lagoon water affects the growth cycles of shrimp. Recent studies suggested that shrimp and fish production in the lagoon had significantly decreased over the years.[11]

Fishermen who engage in Koggala lagoon claimed that their harvest of large mud crabs has decreasing due to the increased salinity as a result of the groyne construction and open mouth throughout the year. Livelihoods of stilt fishermen were endangered too as the fish shoals start swimming inland waters and villagers use large nets to catch them in large batches since the lagoon area is now filled with saline water.[11]

Remedial action

As a solution to this environmental crisis the groyne system was modified in 2013 to allow the natural way of water flushing in the lagoon with proper salinity in the lagoon water.[11] The Practical Action (non-government organisation) together has sought to redress the problems by consulting and coordinating with the Coast Conservation Department, Galle District Secretariat and other authorities such as the Agricultural and Fisheries Departments. The project of rehabilitating the lagoon is also assisted by experts from the Moratuwa University, University of Ruhuna in Sri Lanka and Saitama University in Japan.[12][1]

Research work

A number of studies have been carried out over the past decade on lagoonal hydrology, hydrodynamics and fisheries. The majority of these projects have been done in collaboration with the University of Ruhuna, Moratuwa University and Saitama University.

Ex;

- Applicability of Salinity Stratification Estimation by New Bulk Model for Two Choked Coastal Lagoons in Sri Lanka.[13]

- Mud Crab (Scylla serrata) population changes in Koggala Lagoon, Sri Lanka since construction of the groyne system.[14]

- Effect of inlet morphometry changes on natural sensitivity and flushing time of the Koggala lagoon, Sri Lanka.[15]

- The Current status of density stratification of Koggala lagoon.[16]

- Restoration of Koggala lagoon: Modeling approach in evaluating lagoon water budget and flow characteristics.[4]

- Impact of rubble mound groyne structural interventions in restoration of Koggala lagoon, SriLanka. Numerical modeling approach.[1]

- Some hydrographic aspects of Koggala Lagoon with preliminary results on distribution of the marine bivalve Saccostrea forskalli: Pre-tsunami status.[17]

References

- Gunaratne, G.L.; Tanaka, N.; Amarasekara, P.; Priyadarshana, T.; Manatunge, J. 2011. Impact of rubble mound groyne structural interventions in restoration of Koggala lagoon, Sri Lanka. Numerical modeling approach. Journal of Coastal Conservation 15 (1): 113-121.

- CEA (Central Environmental Authority), 1995. Wetland site report and conservation management plan. Koggala lagoon under wetland conservation project. Sri Lanka Euroconsult, Sri Lanka.

- IWMI (International Water Management Institute), 2006. Sri Lanka Wetlands Database. http://dw.iwmi.org/ wetland/ wetlands info options.aspx?wetland name=Koggala%20Lagoon&wetland/(accessed 10 January 2009)

- Gunaratne, G.L.; Norio, Tanaka; Amarasekara, P.; Priyadarshana, T.; Manatunge, J. 2010. Restoration of Koggala lagoon: Modeling approach in evaluating lagoon water budget and flow characteristics. Journal of Environmental Sciences 22(6):813-819.

- Priyadarshana, T., Manatunge, T. and Wijeratne, N., 2007. Impacts and consequences of removal of the sand bar at the Koggala lagoon mounth and rehabilitation of the lagoon mouth to restore natural formation of the sand bar. Colombo: Practical Action.

- Amarasinghe O (1998) Profitability of current land use practices in five saltwater exclusion and drainage (SWED) schemes. Report of the SWED project under Southern Province Rural Development project, Sri Lanka

- "Home". koggalaexperience.com.

- Prestige Sri Lanka – Koggala (2016) http://www.prestigesrilanka.com/koggala/ (accessed June 01, 2017)

- Amarasekara P., et al., 2016. Mud crab (Scylla serrata) population changes in Koggala Lagoon, Sri Lanka since construction of the groyne system. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management 19(1):83-91

- Tripadvisor reviews – Koggala Lake (2017) https://www.tripadvisor.com.au/Attraction_Review-g1189030-d10392056-Reviews-Koggala_Lake-Koggala_Galle_District_Southern_Province.html (accessed June 01, 2017)

- Rehabilitation of Koggala lagoon now almost on the verge of going barren (2013) http://www.dailymirror.lk/32456/rehabilitation-of-koggala-lagoon-now-almost-on-the-verge-of-going-barren#sthash.4XnXe1A6.dpuf (accessed 01/06/2017)

- Gunaratne, G.L.; Tanaka, N.; Amarasekara, P.; Priyadarshana, T.; Manatunge, J. 2011. Human intervention triggered changes to inlet hydrodynamics and tidal flushing of Koggala lagoon, Sri Lanka. ln: eds. Conditions for entrepreneurship in Sri Lanka: A Handbook. 347.

- Perera, G. L., et al. "Applicability of Salinity Stratification Estimation by New Bulk Model for Two Choked Coastal Lagoons in Sri Lanka." ACEPS 2015 (2015): 102.

- Amarasekara, G. P., et al. "Mud Crab (Scylla serrata) population changes in Koggala Lagoon, Sri Lanka since construction of the groyne system." Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management 19.1 (2016): 83-91.

- Gunaratne, G. L., et al. "Effect of inlet morphometry changes on natural sensitivity and flushing time of the Koggala lagoon, Sri Lanka." Landscape and ecological engineering 10.1 (2014): 87-97.

- Furusato, E., et al. "The Current status of density stratification of Koggala lagoon." (2013).

- Gunawickrama, K.B.S.; Chandana, E.P.S. 2006. Some hydrographic aspects of Koggala Lagoon with preliminary results on distribution of the marine bivalve Saccostrea forskalli: Pre-tsunami status. Ruhuna Journal of Science 1: 16-23.