Kongsi republic

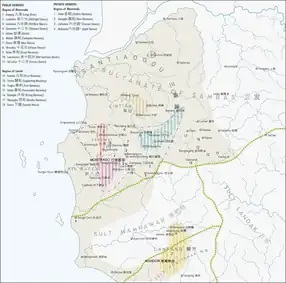

The kongsi republics (Chinese: 公司共和國), also known as kongsi democracies (Chinese: 公司民主國) or kongsi federations (Chinese: 公司聯邦), were self-governing political entities in Borneo that formed as federations of Chinese mining communities known as kongsis. By the mid-nineteenth century, the kongsi republics controlled most of western Borneo. The three largest kongsi republics were the Lanfang Republic, the Heshun Confederation (Fosjoen), and the Santiaogou Federation (Samtiaokioe) after it had split from the Heshun.[1]

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Commercial kongsis were common in Chinese diasporic communities throughout the world, but the kongsi republics of Borneo were unique in that they were sovereign states that controlled large swaths of territory.[1] This characteristic distinguishes them from the sultanates of Southeast Asia, which held authority over their subjects, yet did not control the territory where their subjects resided.[1]

The kongsi republics competed with the Dutch over the control of Borneo, culminating in three Kongsi Wars in 1822–24, 1850–54, and 1884–85. The Dutch eventually defeated the kongsi republics, bringing their territory under the authority of the Dutch colonial state.[2]

Kongsi federations were governed by direct democracy,[3] and were first called "republics" by nineteenth century authors.[4] However, modern scholars hold different views as to whether they should be regarded as Western-style republics or a completely independent Chinese tradition of democracy.[5]

History

Kongsis were originally commercial organizations consisting of members that provided capital and shared profits.[6] They were first established in the late 18th century as the Chinese emigrated to Southeast Asia. The kongsis emerged with the growth of the Chinese mining industry, and were based on traditional Chinese notions of brotherhood. The majority of kongsis began on a modest scale as partnership systems called huis (Chinese: 會; pinyin: huì; lit. 'union').[7] These partnership systems were important economic institutions that existed in China since the emergence of a Song dynasty managerial class in the 12th century.[8] A hui became known as a kongsi once it expanded into a sizable institution that comprised members numbering in the hundreds or thousands.[7]

There are scant records of the first Chinese mining communities. W. A. Palm, a Dutch East India Company representative, reports that gold mines had been established in 1779 around Landak, but the ethnicity of its workers is unknown.[9]

Competition between kongsis increased as old mining sites were exhausted and miners expanded into new territories, which led larger kongsis to incorporate or consolidate from smaller ones. The Fosjoen Federation was formed in 1776 when fourteen smaller kongsis from around Monterado united into a single federation. The federation's leading members were the Samtiaokioe kongsi, which controlled mining sites to the north of Monterado, and the Thaikong kongsi, which controlled sites to the west and southwest of Monterado.[10]

Shortly after the formation of the Fosjoen Federation, Luo Fangbo founded the Lanfang Republic in 1777. Luo emigrated from Guangdong in southern China, accompanied by a group of fellow migrants, and reached Borneo in 1772. Lanfang's early growth is attributed to its commercial ties with the Pontianak Sultanate.[11] The Dutch translation of the Annals of Lanfang implies that Luo Fangbo arrived directly to the port of Pontianak, but he was likely initially involved in the Lanfanghui, an agricultural kongsi that shares the same name as Luo's later kongsi republic. An alternative founding narrative possibly from Malay sources claims that Lanfang originated from a group of smaller kongsis unified by Luo in 1788.[12]

The kongsi republics controlled port and inland towns that allowed them to trade goods without the interference of their Dutch or Malay neighbors. The Chinese kongsis were affiliated with the towns of Singkawang, Pemangkat, Bengkayang, and other settlements.[13] These kongsi towns were home to businesses that served the needs of miners and included services such as pharmacies, bakeries, restaurants, opium dens, barber shops, and schools.[14]

The West Borneo Kongsi Republics were a key factor in the founding of modern Singapore. The Kongsi Republics used Singapore to bypass Dutch trade monopolies and export gold, marine and forestry products. The trade between Borneo and British Singapore exceeded the value of the Dutch trade in Borneo, even though the Dutch controlled two-thirds of Borneo.[15]

Outside Borneo

Kongsi mining operations on Bangka Island were also seen by contemporary European vistors as "a kind of republic", although their early organisational framework remain a matter of speculation.[16]

Kongsi Wars

The Kongsi Wars were three separate wars fought between the Dutch and the kongsi federations in 1822–1824, 1850–1854, and 1884–1885:[17]

- Expedition to the West Coast of Borneo (1822–24)

- Expedition against the Chinese in Montrado (1850–54)

- Chinese uprising in Mandor, Borneo (1884–85)

Most of the kongsi republics were dismantled by the Dutch after the Second Kongsi War. The Lanfang Republic was the last of the kongsi federations to survive because they negotiated a deal with the Dutch that allowed them to remain an autonomous state within the Dutch East Indies.[18] Lanfang could still select its own rulers, but the Dutch had the right to approve the federation's leaders. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Dutch sought to limit the authority of the Lanfang Republic.[18] The Third Kongsi war, a failed rebellion by the Chinese against the Dutch in 1884–1885, brought an end to Lanfang's independence. The territory held by Lanfang was divided between Pontianak, Mempawah, and Landak. The Chinese residents of the former Lanfang Republic were made subjects of Dutch colonial government, but were also expected to pay taxes to local leaders.[19]

Government

The main body of the kongsi republics was the assembly hall (zongting), an assembly of delegates representing the constituent kongsi mining communities.[20][1] The assembly hall exercised both executive and legislative functions.[21]

In the Heshun Confederation, the delegates of the assembly hall were elected every four months.[4]

Nineteenth-century commentators wrote favorably of the democratic nature of the kongsi federation.[22] Historians of this period categorized the kongsi federations as republics.[1] The Dutch sinologist Jan Jakob Maria de Groot was in favor of this interpretation, calling the kongsis "village republics" that partook in the "spirit of a democracy."[4] On the republicanism of kongsis, de Groot wrote:

Already the term kongsi itself, or, according to the Hakka dialect, koeng-sji or kwoeng-sze, indicates perfect republicanism. It means exactly administration of something which is of collective or common interest. It has, therefore, also been used by large corporations and commercial firms. But when used as the term for the political organisations in West Borneo, it should be interpreted as meaning an organisation for governing the republic.[23]

In response to comparisons with Western republicanism, historian Wang Tai Pang has cautioned that "such an approach to the history of kongsi is evidently Eurocentric." He concedes that the federations were similar to Western democracies insofar as they involved the election of representatives. However, Wang argues that the uniquely Chinese characteristics of kongsi federations are overlooked when historians only emphasize the connection between kongsis and republicanism in the West.[24] Instead, kongsis should be viewed as authentically Chinese democracies that developed independently from the influence of Western political institutions.[5] Mary Somers Heidhues stresses that the 19th century understanding of the word "republic" is not identical to the modern interpretation of republicanism. A Dutch commentator from the 19th century would have called any political system without a hereditary ruler a republic.[4]

List of known organizations

Citations

- Heidhues 2003, p. 55.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 116.

- Tai Peng 1994, p. 6.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 60.

- Tai Peng 1979, p. 104.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 54.

- Tai Peng 1979, p. 103.

- Tai Peng 1979, p. 105.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 61.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 63.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 64.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 65.

- Heidhues 2003, pp. 67–68.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 67.

- Ying-kit Chan (2016). "The Founding of Singapore and the Chinese Kongsis of West Borneo (ca.1819–1840)". Journal of Cultural Interaction in East Asia. 7 (1): 99–121. doi:10.1515/jciea-2016-070108. S2CID 164293432.

- David Ownby, Mary F. Somers Heidhues (2016). Secret Societies Reconsidered: Perspectives on the Social History of Early Modern South China and Southeast Asia: Perspectives on the Social History of Early Modern South China and Southeast Asia. Taylor and Francis. p. 75. ISBN 9781315288048.

- Heidhues 2003, p. 80.

- Heidhues 1996, p. 103.

- Heidhues 1996, p. 116.

- Bingling 2000, p. 1.

- Bingling 2000, p. 271.

- Tai Peng 1994, p. 96.

- Tai Peng 1994, pp. 96–97.

- Tai Peng 1994, pp. 4–5.

References

- Heidhues, Mary Somers (1996). "Chinese Settlements in Rural Southeast Asia: Unwritten Histories". Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast China and the Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 164–182. ISBN 978-0-8248-2446-4.

- Heidhues, Mary Somers (2003). Golddiggers, Farmers, and Traders in the "Chinese Districts" of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-733-0.

- Tai Peng, Wang (1994). The Origins of Chinese Kongsi. Pelanduk Publications. ISBN 978-967-978-449-7.

- Tai Peng, Wang (1979). "The Word "Kongsi": A Note". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 52 (235): 102–105. JSTOR 41492844.

- Bingling, Yuan (2000). Chinese Democracies: A Study of the Kongsis of West Borneo (1776-1884). Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies, Leiden University. ISBN 978-9-05789-031-4. Archived from the original on 2017-10-24.