Kosmodraco

Kosmodraco is a genus of large bodied choristodere from the Paleocene of North America. Originally described as a species of Simoedosaurus, it was found to represent a distinct genus in 2022. Multiple fossil skulls show a relatively short and robust snout and a skull that is considerably wider behind the eyes. Two species are currently recognized, K. dakotensis and K. magnicornis.

| Kosmodraco Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

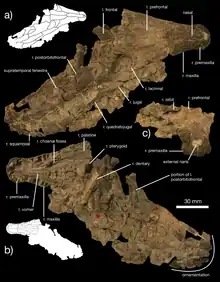

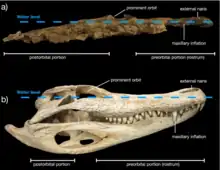

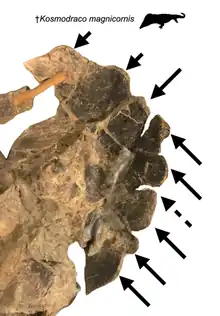

| Holotype skull of K. magnicornis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Choristodera |

| Suborder: | †Neochoristodera |

| Genus: | †Kosmodraco Brownstein, 2022 |

| Type species | |

| Kosmodraco dakotensis (Erickson, 1987)[1] | |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

History and naming

The first specimen now known to belong to Kosmodraco was discovered in 1964 and 1968 in the Polecat Bench Formation (Wyoming). These two skulls, alongside others from Montana's Bear Creek, were reported on briefly by Sigogneau-Russell and Donald in 1978, who regarded them as evidence for the presence of the Eurasian genus Simoedosaurus in North America.[2] However, at the time, these four specimens, although thought to be diagnostic at a genus level, were still unprepared and not assigned to a species. They were subsequently stored in the collection of the Princeton University. It wasn't until a fifth specimen from North Dakota was prepared that the North American remains were named, with Bruce R. Erickson creating the new species Simoedosaurus dakotensis in 1987 and assigning the Princeton material and two additional specimens to it. Erickson, however, did realize there were differences in the specimens, noting that the North Dakota specimen was not just older (mid Tiffanian) than the Princeton fossils (late Tiffanian to Clarkforkian) but also larger, which he initially attributed to differences between growth stages. Later, in 2022, Chase Doran Brownstein reexamined the American Simoedosaurus material, finding that it differed enough to be described as its own genus. Brownstein further considered that the two best preserved Princeton specimens, YPM VPPU 19168 and YPM VPPU 18724, weren't juveniles but should instead be considered a second species. Subsequently, the genus Kosmodraco was erected with K. dakotensis as the type species and a second species in the form of K. magnicornis.[3]

The name Kosmodraco translates to "ornamented dragon" from the Greek κοσμος and Latin draco. The type species was named after the state of North Dakota, while K. magnicornis was named for its large squamosal spikes, derived from the Latin magnum (large) and cornum (horn).[3]

Description

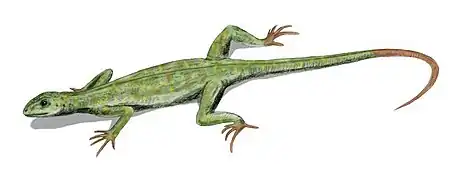

Unlike the well known Champsosaurus, Kosmodraco had an exceptionally brevirostrine skull with the blunt muzzle only making up approximately one third of the total skull length. The posterior region, mostly made up of the squamosal bone, is exaggeratedly broad, giving the skull an overall triangular form. Additionally, all of the skulls show that the cranium of Kosmodraco was exceptionally flat and covered by ridges and furrows along the dorsal and lateral surface. To add to this, four transverse bumps are present on the prefrontals before and between the eyes. The external nares make up around half the width of the bulbous premaxilla and are partly divided by the fused nasal bone. The nasal further extends into the nares through an internasal bar. The premaxilla is only slightly longer than wide and followed by a marked constriction where they meet the maxillae. Four premaxillary teeth of somewhat similar size are followed by forty-five maxillary teeth. In the holotype specimen, the anterior areas of the maxilla show an alternating patter between erupted teeth and empty alveoli, with the second maxilla showing the opposite distribution. Following the 16th tooth, this alternating pattern stops in favor of more continuous tooth rows. Tooth rows are additionally present on the vomers and palatines with small and blunt dentition.[3] The paired prefrontals are anteriorly bifurcated by the nasal and reach to almost the exact halfway point between the orbits where they meet the rectangular frontal bones. The orbits are subangular and directed dorsolaterally, in spite of the flattening of the skull. The shape of the orbits is owed to the fact that the skull roof overhangs large portions of them. Almost the entire medial border of the supratemporal fenestrae consists of the parietal bones, which display a long suture along the center of the skull. The central portion where the two parietals meet is located in a shallow through while the posterior elements of the bones are raised as a crest before meeting the squamosals. The squamosal bones themselves display prominent nodes towards the rear of the skull. The infratemporal and supratemporal fenestrae are similar in size and the maximum distance between the squamosals is only slightly larger than the width of the skull table.[1]

Kosmodraco magnicornis differs from the type species in several key traits. The margin of the rostrum is smooth and confluent unlike the constricted rostrum seen in K. dakotensis. The first three alveoli of the premaxilla are twice as large as any following (except for two where the maxilla is relatively inflated), which differs from the more consistent decrease in size observed in the teeth of the type species. At around the end of the anterior third of the maxilla, the bone is ventrally inflated by two enlarged maxillary alveoli in a condition comparable to the area right behind the premaxillary-maxillary suture in the type species, however greatly exaggerated in a manner more akin to modern crocodylians. This species has fewer teeth than K. dakotensis, with only thirty-one maxillary teeth opposed to forty-five. The orbits are more subcircular and possibly possessed higher raised orbital margins, however due to the crushing the holotype of K. dakotensis this cannot be said for certain. Much like the holotype, Kosmodraco magnicornis bears eight nodules along the posterior edge of the squamosal. However, unlike in the holotype, these nodules are much more developed, exceeding any other late Mesozoic or Cenozoic choristodere and much more resembles those of Coeruleodraco and Monjurosuchus. These ornaments are what give the species its name.[3]

Postcranial material is known from both species. Kosmodraco dakotensis is associated with eight cervical vertebrae and at least sixteen additional centra thought to be presacrals. Three sacral vertebrae were described (however one of them was lost) and multiple caudals from various sections of the tail. Among the cervicals, the axis has a stout neural arch and large crest that projected over the centrum of the atlas, likely as an anchor for the musculature of the head. This differs significantly from the low and broad neural spine observed in Champsosaurus gigas. Thirty-four complete vertebrae are known from K. magnicornis and show very similar morphology to the type species.[3] The shoulder girdle is known from Kosmodraco magnicornis with a long blade of the scapula and a longer coracoid blade. Of the pubic bones, the ischium and pubis are only well enough preserved for a very general reconstruction. The ilium is known from more complete material. The acetabulum has a rounded rather than pointed bottom and rises almost vertically towards the iliac blade unlike in Simoedosaurus. Although several limb bones are known from fragments, only a single femur is complete. This femur is longer and more slender than fossils known from Europe and the condyles are relatively weak, with narrow articular surfaces.[1]

Kosmodraco was perhaps among the largest amphibious predatory animals of its time and range with the type species having an estimated body length of 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft),[1] perhaps even 5 m (16 ft),[4] rivaling even most crocodylomorphs of the Paleocene. K. magnicornis was on the smaller side of the spectrum with a skull length of 431 mm (17.0 in), which still leaves it as the fourth largest known choristodere behind K. dakotensis, Champsosaurus gigas and Simoedosaurus.[3]

Phylogeny

Phylogenetic analysis consistently recovered Kosmodraco as clading together with the Old World choristodere Simoedosaurus and Tchoiria, forming the family Simoedosauridae within Neochoristodera. Within the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Brownstein, differences within Simoedosauridae are restricted to the relationships between the two basalmost taxa, both species of Tchoiria. However, their placement as basal simoedosaurids is consistent amongst all of them. Depicted below are the results of the Bayesian phylogenetic analysis.[3]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Although niche partitioning is a common explanation for predator-rich ecosystems and would fit the distinctive skull shapes of both Kosmodraco and the contemporary Champsosaurus, Brownstein argues that in the case of Kosmodraco the vastly different skull shapes have an evolutionary rather than strictly ecological origin. The brevirostrine skull shape of the animal has repeatedly been compared to both alligatoroids and gars of the genus Atractosteus (including the alligator gar), with all of them having evolved relatively short but robust skulls.[1] Kosmodraco additionally shows that both the orbits and nares were raised, an adaption to a semi-aquatic lifestyle commonly seen in crocodilians and absent in gars. In the reverse case, gars and Kosmodraco share the presence of palatal teeth which are not found in alligators. The overall skull shape is also closer to that of gars with a more triangular shape, while the skulls of alligatoroids are typically broader and more subrectangular. Kosmodraco however differs from both with its extremely flattened skull and characteristically expanded postorbital region. As far as the postcrania are concerned, Kosmodraco possessed three sacral vertebrae bearing distinctive prominences for ligaments and muscles to attach to. These attachments for sacral and caudal soft tissue differ from what is observed in crocodilians today and make it subsequently difficult to infer the precise ecological niche these animals would have inhabited.[3]

Given the differing skull shapes, it is likely that the contemporary Champsosaurus and Kosmodraco, despite being similar in size, preyed on different animals; the former filling a niche possibly similar to extant gharials, while the latter, with its more robust and broader skull, had a generalized diet of fish and small vertebrates. More similar to Kosmodraco were the various brevirostrine crocodilians found in Paleocene North America. In the Fort Union Formation, for example, Champsosaurus gigas and a species of Kosmodraco coexisted with possibly as many as four different crocodilians. Most of these species, however, like Ceratosuchus and Allognathosuchus, were notably smaller than either choristodere. The exception is Borealosuchus, which with a length of up to 4 meters rivaled Kosmodraco in size.[4] Given Kosmodraco's size and robust morphology, Erickson considers it possible that it was capable of competing with crocodilians. This could explain injuries found on the bones of Kosmodraco as described by Erickson, although they might have been caused by intraspecific combat.[1]

References

- Erickson, B. R. (1987). "Simoedosaurus dakotensis, new species, a diapsid reptile (Archosauromorpha; Choristodera) from the Paleocene of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (3): 237–251. Bibcode:1987JVPal...7..237E. doi:10.1080/02724634.1987.10011658. JSTOR 4523144.

- Sigogneau-Russell, D.; Donald, B. (1978). "Presence du genre Simoedosaurus (Reptilia, Choristodera) en Amerique du Nord". Geobios. 11 (2): 251–255. Bibcode:1978Geobi..11..251S. doi:10.1016/s0016-6995(78)80091-6.

- Brownstein, C.D. (2022). "High morphological disparity in a bizarre Paleocene fauna of predatory freshwater reptiles". BMC Ecol Evol. 22 (34): 34. doi:10.1186/s12862-022-01985-z. PMC 8935759. PMID 35313822.

- Matsumoto, R.; Evans, S.E. (2010). "Choristoderes and the freshwater assemblages of Laurasia". Journal of Iberian Geology. 36 (2): 253–274. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2010.v36.n2.11.