Krupp steelworks

%252C_Essen_LCCN2014703497.jpg.webp)

The Krupp steelworks, or Krupp foundry, or Krupp cast steel factory (German: Krupp-Gussstahlfabrik [Guss+stahl+fabrik]) in Essen is a historic industrial site of the Ruhr area of North Rhine-Westphalia in western Germany that was known as the "weapons forge of the German Reich" (Waffenschmiede des Deutschen Reiches).[1]

Overview

Established in 1811 by Friedrich Krupp, the massive Kruppwerke occupied up to 5 km2 (1.9 sq mi) by 1912. From the Franco-Prussian War through the Great War and beyond, Krupp manufactured armaments used by German armies.[2] The Krupp factory was functionally demolished by Allied bombing of Essen in World War II, machines and the scrap metal were sold overseas as part of German reparations. The site was largely abandoned between 1945 and 2007. In 2010, ThyssenKrupp established its new headquarters on the site and launched the Krupp District urban redevelopment project.

Today, some of the Kruppstadt (Krupp city) buildings that survived have been repurposed to house university institutes and schools, another is the parking for an IKEA. The 1938 administration building still stands although the 1908 landmark tower was demolished in 1976. The Colosseum Theater is the converted former 8th. Mechanical workshop of the Krupp plant. The factory railway that circumnavigated the site in the east, built as part of the Essen ring railway in 1872-1874, is partially extant in the steel beams of a railway bridge now used as a pedestrian crossing over Altendorfer Straße.

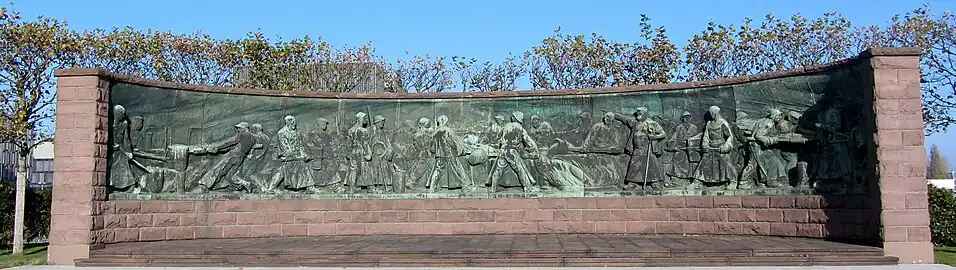

Monument to Friedrich Krupp's 1823 process for making crucible steel

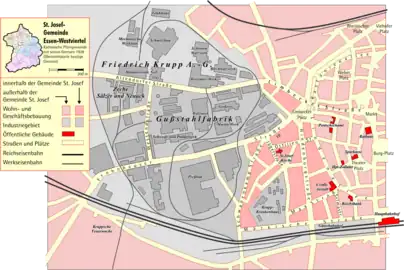

Monument to Friedrich Krupp's 1823 process for making crucible steel Map of the cast steel factory in St. Josef, Essen, Ruhr area (in German)

Map of the cast steel factory in St. Josef, Essen, Ruhr area (in German) Aerial view of ThyssenKrupp headquarters

Aerial view of ThyssenKrupp headquarters

History

The Krupp steelworks was established in 1811 by Friedrich Krupp, originally near the Berne River. He oversaw construction of a production plant in 1812–13 with melting furnaces and a hammer mill for further processing the steel. By 1817 he was producing an assortment of items including tanning tools, drills, machining tools, coin stamps and coin rollers. In 1818 he moved to the site at Limbecker Platz that would eventually become the massive Krupp City.

Friedrich Krupp finally mastered crucible steel in 1820 and produced saws and blades but died in 1826 with the company heavily in debt. His widow Therese Wilhemi Krupp and his sister Helene Krupp von Müller took over and successfully ran the company until 1848.

Alfred Krupp, son of Friedrich and Therese, developed the seamless train wheel that eventually became the three-ring logo of the company. The company had 1,000 employees at the time. The company started manufacturing and selling cannons and by 1870, Krupp became the largest industrial company in Europe. By 1873, the plant in the west of Essen was 360 hectares (890 acres; 3.6 km2; 1.4 sq mi) in size. By the time Alfred Krupp died in 1887, the company employed 20,000 people. His son, Friedrich Alfred Krupp, successfully expanded the lines of the business and at the time of his death in 1902, the company employed 45,000. By 1910, it was 67,000 people. In 1912 the area of the factory site in Essen was specified as 5 km2 (1,200 acres; 500 hectares; 1.9 sq mi). Friedrich Alfred Krupp's heir was his daughter Bertha Krupp (Big Bertha artillery is named for her) who married Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach and whose eight children had the last name Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach. World War I saw the business explode from 81,000 to 200,000 employees but the terms of the Treaty of Versailles prohibited weapons production so the company shifted to producing rail cars. Lokomotiv- und Waggonbaufabrik Krupp was established at Krupp City in 1919.

The prominence of the Essen site to the overall Krupp conglomerate was diminished in the 1920s. The number of employees fell in 1926 to 25,000 people working in Essen, a third of the company's overall workforce.

Weapons production resumed in 1933. Hitler visited in 1934, 1936, and 1937; Benito Mussolini was his guest for the 1937 tour. (In one of Hitler's obnoxious speeches he said he wanted German boys to be as hard as Krupp steel.)[3] Orders increased and profits were good. Two coal mine businesses were merged into the Sälzer-Amalie colliery on the factory premises. Civilian trucks and locomotive production continued on a smaller scale as capacity was reorganized to feed the war machine. The Krupp factory manufactured the giant Dora gun. Krupp used prisoners of war and concentration camp inmate labor to keep the factory running when labor shortages became a problem. Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach's health began to fail in 1943, so Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach took control.

During World War II, the Allies did not successfully hit the Krupp factory until March 1943, in part because of the successful Krupp decoy site. In total, the Krupp plant was attacked 55 times from the air. About a third of the buildings on the 1.5 km2 (150 hectares; 370 acres; 0.58 sq mi) were completely destroyed, and another third were substantially damaged. After the war, 22 buildings of the Krupp military-industrial complex were demolished. A further 127 buildings were released for "peace production" including the locomotive and wagon construction factory. After being released from Allied detention, Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach took over the company management again in March 1953. A handful of new businesses moved into what had once been Krupp City, but the conglomerate larger operations at the site were shut down decade by decade and by the 1980s the area languished. ThyssenKrupp headquarters with its six large office buildings moved back to the site in 2010.

Automobile Hall at Krupp-Werk, 1923 (Bundesarchiv)

Automobile Hall at Krupp-Werk, 1923 (Bundesarchiv).jpg.webp) A medal from Hitler for the metal company, 1940

A medal from Hitler for the metal company, 1940 RAF Bomber Command planes over Krupp steelworks

RAF Bomber Command planes over Krupp steelworks Kruppworks 1961

Kruppworks 1961

See also

- Occupation of the Ruhr (1923)

- Battle of the Ruhr (1943)

- Remilitarization of the Rhineland

- The Arms of Krupp, 1587–1968 by William Manchester

References

- "Vor 75 Jahren verhaftet – Alfried Krupp – Erbe der Waffenschmiede der Nazis". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Birkenstock, Günther (4 October 2012). "The rise of the Krupp steel empire". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Martin Roddewig (28 November 2012). "Swift as a greyhound, as tough as leather, and as hard as Krupp's steel". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

External links

Media related to Krupp Gussstahlfabrik at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Krupp Gussstahlfabrik at Wikimedia Commons