La Vega Parish

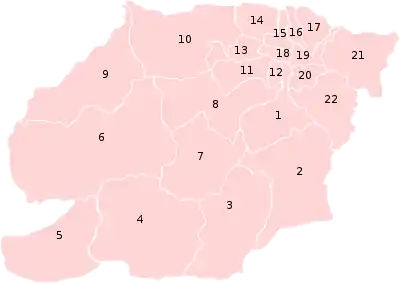

La Vega is a parish located in the Libertador Bolivarian Municipality, central of the city of Caracas, Venezuela. Is one of the 22 parishes of Libertador Municipality and one of the 32 parishes of Caracas.

La Vega | |

|---|---|

| |

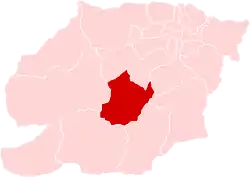

La Vega as seen located in the Libertador municipality. | |

| Coordinates: 10°28′03″N 66°56′51″W | |

| Country | Venezuela |

| Federal district | Distrito Capital |

| Municipality | Libertador |

| Area | |

| • Land | 12.9 km2 (5.0 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 202,206 |

It is located in the center-west of Libertador Municipality. Limit to the north with the parishes El Paraíso, Antímano and Santa Rosalía; to the south with Coche, Caricuao, El Valle and Antímano parishes; to the east, it borders Coche, Santa Rosalía, El Valle and El Paraíso parishes; to the west it limits with Antímano, Caricuao and El Paraíso parishes.

History

The town of La Vega was originally the settlement of the slaves who tilled the land in the Hacienda Montalbán, created by the Spaniards as sugar cane mill. Being populated in its beginnings by the Indians Toromaimas

Then it was founded as Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá de la Vega on July 18, 1813, the then town remained without major variations until 1907 when Engineer Alberto Smith constituted the "Compañía Anónima Fábrica Nacional de Cementos", which in that epoch began with a production of 50 sacks per day. In 1916, Mr. Carlos Delfino acquired 75% of the capital of that company and renamed it "Cementos La Vega". This company, with the most advanced technology of that time, boosted production and managed to become one of the most important cement companies in Latin America. In the mid-twentieth century began to settle in the mountains workers, mostly workers from the interior of Venezuela and European immigrants who were later displaced by Colombians and Ecuadorians, the lack of planning made the growth was excessive building homes in precarious conditions known as "ranchos". In the plain to the north of the parish, an eminently residential urbanization of vertical type called Montalbán was created. Later, the Juan Pablo II Urbanization was built.

The contemporary vegueño is in many cases, descendant of the first ones that arrived during the process of industrialization and developed their productive activity in the companies of the sector. Others are the children of the emigrants who arrived from the interior in past decades, to look for employment opportunities in the city and used La Vega to plant a ranch to house their families. In any case, this work force is employed outside La Vega.

However, the time spent in their community has created an ingrained parochial feeling: the pride of being from La Vega. Because in La Vega they were born, they grew up, they got married, they work outside but they think about her and they go back to her.

All this human flow, is concentrated on weekends in their respective areas, between the bustle of peddlers and music at full volume of the yiceros, housewives discuss the price of vegetables, how expensive is the tomato and the lack of water in the most remote neighborhoods of La Vega, also in that corner of Carmen, where the bakery and pastry shop "Bethany" is located, some Portuguese languors make efforts to communicate in an intricate Castilian mixed with words from their peninsula of origin, that almost nobody understands. In the religious plane we can find the Santo Cristo de La Vega Church, which was built in the year 1568, by Francisco Infante and Garci González de Silva. Traditionally Holy Week is celebrated on Holy Wednesday, the procession which consists of taking the Virgin Mary and the Nazarene to walk the streets of this populous parish.

According to police information that Efecto Cocuyo had access to, in January 2021 members of the mega-gang that operates in Cota 905 in Caracas and the "El Loco Leo" gang in El Valle attempted to rise up against the local authority to turn it into a no-go area.[2] In the morning of 8 January, commissions of the Venezuelan National Police (PNB), of the Special Armed Forces (FAES) and the Venezuelan National Guard took control of La Vega Parish.[3] According to police sources, all the deceased had criminal background or were in police registries, but relatives assured that many were arrested after raiding their homes and that they were later executed. Witnesses declared that many of the victims that were identified in the Bello Morgue of Caracas were first alive at the moment of the arrest.[4] By 11 January, no public official of the Nicolás Maduro administration had declared about the events nor offered a death toll.[2] The NGO Monitor de Víctimas (Victims Monitor) extraofficially registered 24 deaths and identified 10 people, three of whom were minors.[3] Former prosecutor and director of the Public Ministry, Zair Mundaray, declared that the bodies of the deceased had a "ballistic pattern that demonstrates extrajudicial killings".[5]

See also

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Venezuela). "Distrito Capital. Densidad poblacional según parroquia, 2011" (Excel). Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Provea registra 23 muertos en masacre de La Vega e insta al Defensor del Pueblo a pronunciarse". Efecto Cocuyo. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Marra, Yohana (11 January 2021). "Tres menores de edad entre los identificados de la masacre de La Vega". Crónica Uno. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Masacre de La Vega, Caracas: policía juzga, ejecuta y después viste a los muertos". El Estímulo. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Denuncian que muertos de la masacre de La Vega presentan "un patrón balístico de ejecuciones extrajudiciales"". Monitoreamos (in Spanish). 2021-01-11. Retrieved 2021-01-12.