Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

Ojibwe: Odaawaa-zaaga'iganiing | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band | |

| Total population | |

| 7,275[1] (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Ojibwe | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Ojibwe people |

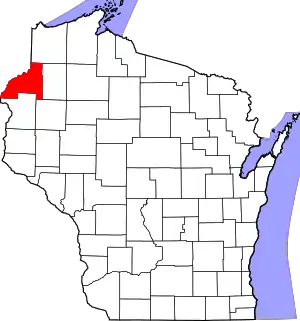

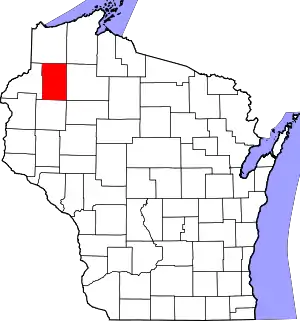

The Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe (Ojibwe: Odaawaa-zaaga'iganiing) is one of six federally recognized bands of Ojibwe people located in present-day Wisconsin. It had 7,275 enrolled members as of 2010.[1] The band is based at the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation in northwestern Wisconsin, which surrounds Lac Courte Oreilles (Odaawaa-zaaga'igan in the Ojibwe language, meaning "Ottawa Lake"). The main reservation's land is in west-central Sawyer County, but two small plots of off-reservation trust land are located in Rusk, Burnett, and Washburn counties. The reservation was established in 1854 by the second Treaty of La Pointe.[2]

The Lac Courte Oreille ceded land under a treaty they signed with the United States in 1837, the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, and the first 1854 Treaty of La Pointe. The tribal reservation has a land area of 108.36 square miles (280.65 km2), including the trust lands[3] and a population of 2,968 persons as of the 2020 census.[4] The most populous community is Little Round Lake, at the reservation's northwest corner. It is south of the non-reservation city of Hayward, the county seat of Sawyer County.

Reservation

Lac Courte Oreilles is a land which is almost entirely covered by a forest and several lakes. To the northeast and east of Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation is Chequamegon National Forest, which was established in 1933 during the Great Depression. White-owned lumber companies had cleared the land of the trees earlier in the century and, during the Depression, Civilian Conservation Corps workers planted new trees.[2]

Today, both the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Chequamegon National Forest are recovering from the clear-cutting conducted by the lumber companies. Numerous lakes are within the borders of Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation or border it, including Ashegon, Blueberry, Chief, Cristner, Devils, Green, Grindstone, Gurno, Lac Courte Oreilles, Lake Chippewa, Little Round, Little Lac Courte Oreilles, Pokegama, Rice, Scott, Osprey, Spring, Summit, and Tyner lakes.

Within the Reservation borders is the protected Grindstone Creek State Wildlife Management Area. Wild rice, called manoomin in Ojibwe language, grows on many of the waterways on the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation. Citizens of the Reservation still harvest it in the traditional way and it is one of the staples of the community.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the combined reservation and off-reservation trust land have a total area of 124.35 square miles (322.07 km2), of which 108.36 square miles (280.65 km2) is land and 15.99 square miles (41.4 km2) is water.[3]

Reservation demographics

Lac Courte Orellies is one of several reservations that has a relatively large non-Native population within its borders. Broken treaty promises allowed settlement by white squatters and the US allowed them to stay.

As of the census of 2020,[4] the combined population of the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and off-reservation trust land was 2,968. The population density was 27.4 inhabitants per square mile (10.6/km2). There were 2,102 housing units at an average density of 19.4 per square mile (7.5/km2). The racial makeup of the reservation and off-reservation trust land was 72.3% Native American, 21.3% White, 0.2% Black or African American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.2% from other races, and 6.0% from two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 1.7% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

According to the American Community Survey estimates for 2016-2020, the median income for a household (including the reservation and off-reservation trust land) was $33,590, and the median income for a family was $49,706. Male full-time workers had a median income of $30,801 versus $28,974 for female workers. The per capita income was $19,251. About 27.5% of families and 33.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 45.4% of those under age 18 and 13.6% of those age 65 or over.[5] Of the population age 25 and over, 90.0% were high school graduates or higher and 15.3% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[6]

Government and economy

The band is federally recognized as a tribe and has its own elected government, consisting of a chairman and tribal council. Members are elected from enrolled members of the tribe and elected to serve four-year terms with elections staggered every two years. [7]

It owns and operates a tribal college, Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College, located in Hayward. The Tribe owns and operates the Sevenwinds Casino, to generate revenue for its people's welfare. It also operates a community radio station, WOJB-FM.

The reservation hosts an "Honor the Earth" Pow Wow every summer. Rock drummer Mickey Hart's recording of some of the performers, Honor The Earth Powwow--Songs Of The Great Lake Indians, became a minor national hit in 1991.[8]

History

The Anishinaabe, part of the Algonquian languages family of peoples originating along the Atlantic Coast, migrated west and have lived in what is now northern Wisconsin for a long time. Following the Seven Fires Prophecy, Anishinaabe leaders ordered their warriors to expand to the west after they learned that the people mentioned in the prophecy had invaded in the East. They also sent their soldiers as far east as Maine and as far south as Florida, to defend Indian land from the white invaders. According to Native American historian William W. Warren, Anishinaabe people were living in northern Wisconsin before 1492 and the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean area.

The Dakota Indians referred to the Anishinaabe as the Ra-ra-to-oans, which means "People of the Falls." The French adopted the name.

In the 17th century, "The arrival of French fur traders to the area provided the Chippewa with a market for their hunting skills, and in exchange, the Chippewa received guns, knives, cloth, liquor, and other manufactured goods. The acquisition of these products changed their lives and disturbed the nomadic nature of their patterns of existence. The French fur traders were readily accepted by the Chippewa because of the way they embraced the Chippewa culture. They learned the language and married Chippewa women."[9]

During 1661-62, the French fur traders Radisson and Groseilliers journeyed four days from Madeline Island to a Huron Indian village, believed to be near the present village of Reserve on the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation. The French received permission to use the Indian lands for passage.[2]

The French and their Indian allies gained control of the lands east of Lake Michigan: what are now known as New York, southern Ontario, and parts of Ohio and Pennsylvania. That changed in 1680 after Anishinabe warriors were sent to the east to war on the white invaders and their Indian allies. By 1700, Anishinaabe soldiers had driven the whites back to the eastern coast, where they had large fortified settlements. Anishinaabe soldiers subjugated the Indian allies of the whites, who are known historically as the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Anishinaabe people absorbed them into their population in New York and southern Ontario.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, control of northern Wisconsin and northeastern Minnesota was hotly contested by the Santee Sioux (Dakota) and the Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe/Anishinaabe). By the close of the 18th century, the Ojibwe had pushed the Dakota out of Wisconsin and much of northern Minnesota to areas west of the Mississippi River. Although the 1825 First Treaty of Prairie du Chien recognized only a small portion of present-day Wisconsin as Dakota land, throughout the 18th and well into the 19th centuries, the Dakota and Ojibwe continued to launch military expeditions into each other's territories. The Battle of the Brule, which took place in October, 1842 was a battle between the La Pointe Band of Ojibwe Indians and a war party of Dakota Indians, with the Ojibwe being victorious.

Later on in the 18th and early 19th centuries, more wars were fought between the Anishinaabeg and European Americans. English colonists had taken over rule from the French in eastern Canada and also established dominance up to the Appalachian Mountains in the Thirteen Colonies below the Great Lakes. At the end of the 18th century, those colonies achieved independence as the United States of America. Its settlers had already invaded Indian country west of the Appalachians, and more moved west. The US defeated an alliance of tribes in the Northwest Indian War, opening the area north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi to more settlement by European Americans.

The War of 1812 between the US and Great Britain was entered into by the Great Lakes Anishinaabeg on the side of Britain in an effort to defend their land. After the war, they signed treaties with the United States, but these were not honored. American settlers continued to encroach on their territories around the Great Lakes. In 1854, the second Treaty of La Pointe with the US established what is now the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation, in addition to other reservations for Ojibwe in this region.[2]

In the late 19th century, with increased European-American settlement, the United States wanted to relocate all Native Americans from Michigan and Wisconsin to west of the Mississippi River, proposing to consolidate them on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. The proposed relocation plan proved futile. The tribes resisted and a minor rebellion broke out in 1898 on the Leech Lake Reservation of northern Minnesota. The US finally left the tribes in small rural reservations in these areas.

Communities

Lac Courte Oreilles reservation has several communities within its borders; most are predominately Native American in population. Little Round Lake is the largest community within the reservation, with a population of 1,081 in the 2010 census. Native Americans make up 90% of the community's population.

Chief Lake is a predominantly Indian community, with 80% of the population. New Post has 72% Ojibwe residents. Reserve has a population that is 88% Native American. Northwoods Beach is located on the Reservation's west end, between Grindstone Lake and Lac Courte Oreilles.

None of the Lac Courte Oreilles communities has developed to the level of a city or town. Most of the population of Reserve is scattered, although the heart of the community is a more dense village. The community's housing units are located in the woods.

Notable tribal members

- Ah-shah-way-gee-she-go-qua (Aazhawigiizhigokwe, Hanging Cloud), 19th c. Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe woman warrior

- David Wayne "Famous Dave" Anderson, entrepreneur

- Diane Burns, poet

- Paul DeMain, journalist and founder of News from Indian Country. He is known for late 20th-century reporting on the unsolved murder of AIM activist Anna Mae Aquash, related to murders of FBI agents at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. His work contributed to the re-opening of her case by federal and state officials in the late 20th century and the prosecution of people for her kidnapping and murder. He publicly withdrew his support for Leonard Peltier, an AIM activist previously convicted and sentenced to prison in relation to the deaths of two FBI agents.[10]

- Jim Denomie, visual artist

- Nenaa'angebi (Beautifying Bird), twin son of Ozaawindib, and a prominent leader of the Ojibwe in the 19th century

- Ozaawindib (O-za-win-dib, also known as Yellow Head) was an 18th-century Ojibwa chief of the Prairie Rice Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians. Originally located near Rice Lake, Wisconsin, the band consolidated with the Lac Courte Oreilles Band. He was of the Niibinaabe-doodem (Merman Clan). He fought in the Battle of Prairie Rice Lake in 1798.[11] He and Wolf's Father were killed by a Dakota raider while they were hunting at the mouth of Hay River.[12]

- Chief Zhaagobe (Six), twin son of Ozaawindib and also a chief of the Ojibwe in this area in the 19th century.

See also

References

- Tribes of Wisconsin (PDF). Madison: Wisconsin Department of Administration Division of Intergovernmental Relations. July 2022. p. 49. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- "Our History". Lcotribe. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- "2020 Gazetteer Files". census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- "2020 Decennial Census: Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, WI". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, WI". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Selected Social Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, WI". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Government". Lcotribe. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- Bill Miller (October 1, 1993). "Native Tongues". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Our History". Lcotribe. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- Deborah Kades, "Native Hero", Wisconsin Academy Review 2005, accessed 9 June 2011

- Mashkode-manoominikaani-zaaga'igan (Prairie Rice Lake) is Prairie Lake of Chetek, Wisconsin.

- History, p. 320

- Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Wisconsin, United States Census Bureau

External links

- "Lac Courte Oreilles", Tribal government website

- Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Schools, Official website

- LCO Casino website

- Honor the Earth Pow Wow, Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Schools], Official website

- Lac Courte Oreilles Times, LCO-owned and operated, community Newspaper